Worldly passions have always made a part of religious fanaticism, and frequently, on the contrary, true faith by some abstract ideas feeds political fanaticism.

The mixture is found everywhere, but it is on the proportion of the ingredients that the good and the mischief depend. Social order is in itself an intricate and irregular edifice. In the meantime, it cannot be conceived other than it is, but the concessions with which it is necessary to comply in order that it may subsist torment exalted souls with pity, satisfy the vanity of some, and provoke the irritation and the desires of the greater number. It is to this state of things, more or less strongly marked, more or less softened by morals, manners, and intelligence, that the political fanaticism of which we have been witnesses in France must be ascribed. A sort of frenzy seized the poor in the presence of the rich. The distinctions of nobility adding to the jealousy that property inspires, the people were proud of their multitude, and all that constitutes the power and splendor of the few appeared to them mere usurpation. The germs of this sentiment have existed at all times, but never was human society felt to tremble at its foundations till the era of terror in France. We need not be surprised if this hateful scourge has left deep traces in men’s minds, and the only reflection in which we can indulge is that the remedy for popular passions is to be found not in despotism but in the sovereignty of law.

The two elements of religious fanaticism and political fanaticism always subsist: the wish to rule in those who are at the top of the wheel, the eager desire to make it revolve in those who are beneath. Such is the principle of every commotion; the pretext changes, the cause remains, and the reciprocal fury continues the same. The quarrels of patricians and plebeians, the servile war, the war of the peasants, that which still goes on between the nobles and the commonality, have all equally had their origin in the difficulty of maintaining human society without disorder and without injustice. Men could not exist at this period either apart or united if respect for the law were not established in their minds. Crimes of every sort would arise from that very society which ought to prevent them. The abstract power of representative governments does not irritate the pride of men, and it is by this institution that the torches of the furies are to be extinguished. They were lit in a country where everything was self-love, and self-love irritated does not, with the people, resemble a fugitive shadow; it is a feeling that can be gratified only by murder.

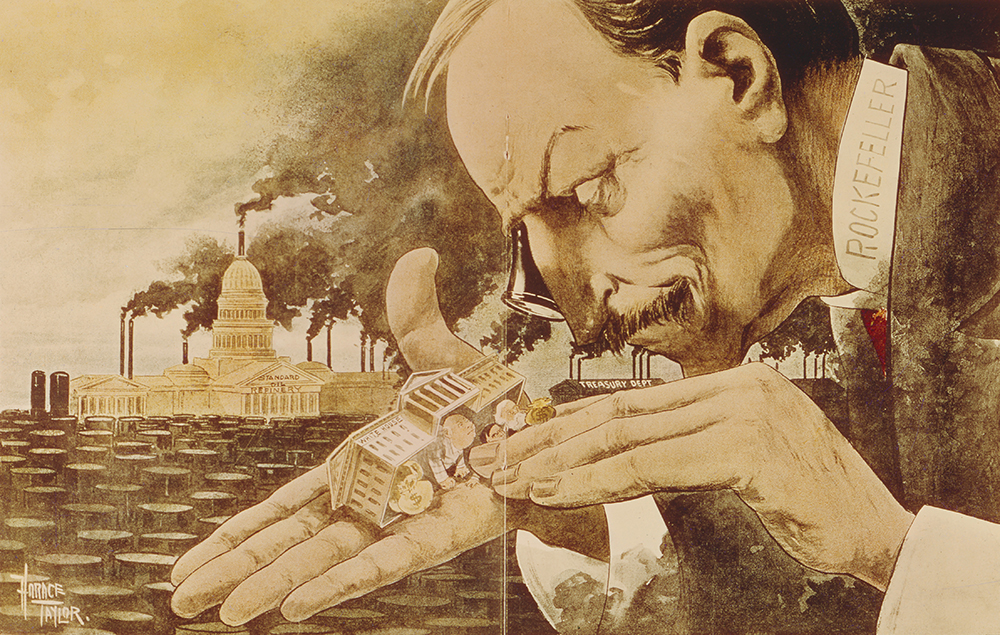

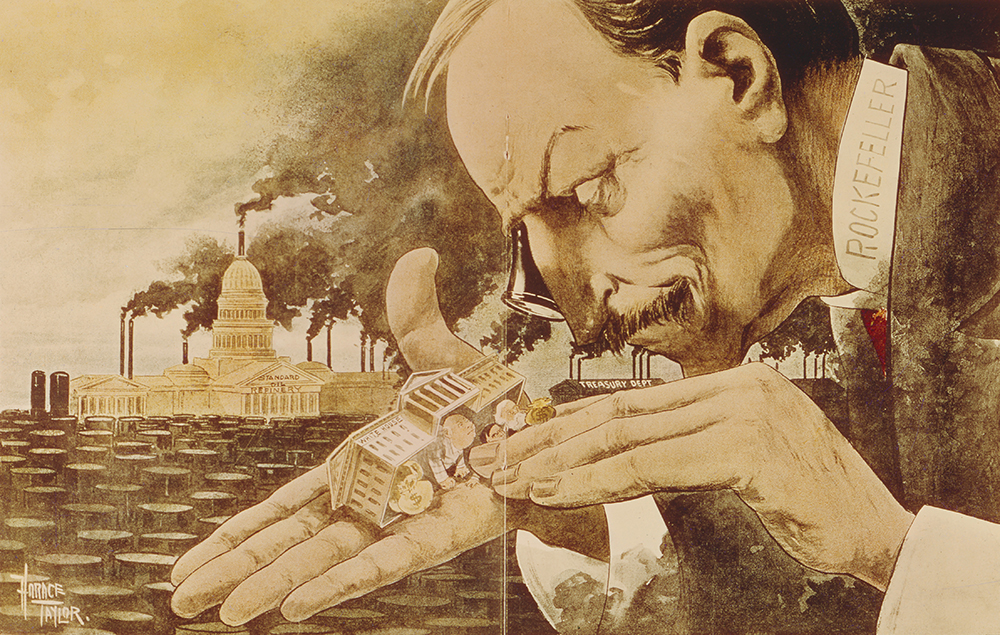

The Trust Giant’s Point of View, by Horace Taylor, 1900. Snark / Art Resource, NY.

Massacres not less frightful than those of the reign of terror have been committed in the name of religion. The human race has exhausted itself for many centuries in useless efforts to constrain all men to the same belief. That end could not be attained, and the simplest idea, toleration, such as William Penn professed, has forever banished from North America the fanaticism of which South America has been the horrid theater. It is the same with political fanaticism; liberty alone can calm it. After a certain time, some truths will no longer be denied, and old institutions will be spoken of as ancient systems of physics, now entirely effaced by the evidence of facts.

As the different classes of society had scarcely any relations with each other in France, their mutual antipathy was of course the stronger. There is no man, not even the most criminal, whom we can detest when we know him, as we do when he is only delineated to us. Pride places barriers everywhere and limits nowhere. In no country have men of birth been such complete strangers to the rest of the nation. They came into contact with the second class only to bruise it. Elsewhere, a careless good nature, habits of life even somewhat vulgar, contribute to confound men, between whom the law makes distinction, but the elegance of the French nobility increased the envy that they inspired. To imitate their manners was as difficult as to obtain their prerogatives. The same scene was repeated from rank to rank. The irritability of a nation, lively in the extreme, inclined each one to be jealous of his neighbor, of his superior, of his master. And all, not satisfied with ruling, labored for the humiliation of each other. It is by multiplying political relations between different ranks, by giving them the means of being mutually serviceable, that we can mollify in the heart the most horrible of passions—the hatred of men against their fellow mortals, the mutual aversion of creatures whose remains must all repose under the same earth and be together reanimated at the last day.

From Considerations on the French Revolution. The daughter of Louis XVI’s finance minister, Mme de Staël was protected from violence during the French Revolution by her Jacobin sympathies as well as the diplomatic status of her first husband, a Swedish ambassador, which allowed the couple to flee to Switzerland at the beginning of the Reign of Terror in 1793. “Public safety,” she writes elsewhere in this posthumously published treatise, is “a fatal expression that implies the sacrifice of morality to what it has been agreed to call the interest of the state, that is, to the passions of those who govern.”

Back to Issue