That obtained in youth may endure like characters engraved in stones.

—Ibn Gabirol, 1040Social Clearinghouse

Owen Johnson calls colleges “splendidly organized institutions for the prevention of learning.”

By the opening of the winter term, Stover, the enthusiast, had begun to see the weakness of movements that must depend on organization. The debating club, which had started with a zest, soon showed its limitations. Once the edge of novelty had worn off, there were too many diverting interests to throng in and deplete the ranks.

When, following Regan’s suggestion, they had attempted a new division on the lines of the political parties, the result was decidedly disappointing. There was no natural interest to draw upon, and the political discussions, instead of fanning the club into a storm of partisanship, lapsed into the hands of perfunctory debaters.

Regan himself took his disillusionment much to heart. They discussed the reasons for the failure one stormy afternoon at one of their informal discussions, to which they had returned with longing.

“What the devil is the matter?” said the big fellow savagely. “Why, where I come from, the people I see, every mother’s son of them, feed on politics, talk nothing else—they love it! And here if you ask a man if he’s a Republican or a Democrat, he writes home and asks his father. A condition like this doesn’t exist anywhere else on the face of the globe. And this is America. Why?”

When he had propounded the question, there was a busy, unresponsive puffing of pipes, and then Pike added, “That’s what hits me, too. Just look at the questions that are coming up; popular election of senators, income tax, direct primaries; it’s like building over the government again, and no one here cares or knows what’s doing. I say, why?”

“There may be fifty-two reasons for it,” said Brockhurst, in his staccato, biting way. “One is, our colleges are all turning into social clearinghouses, and everyone is too absorbed in that engrossing process to know what happens outside; second is the fact that our universities are admirably organized instruments for the prevention of learning!”

“Good old Brocky,” said Swazey with a chuckle. “Just what I like: stormy outside, warm inside, and Brocky at the bat. Serve ’em up.”

Brockhurst, who was used to this reception of his pointed generalizations, paid no heed. He, too, had grown in mental stature and in control. A certain diffidence was over him, and always would be; but when a subject came up that interested him, he forgot himself and rushed into the argument with a zeal that never failed to arouse his listeners.

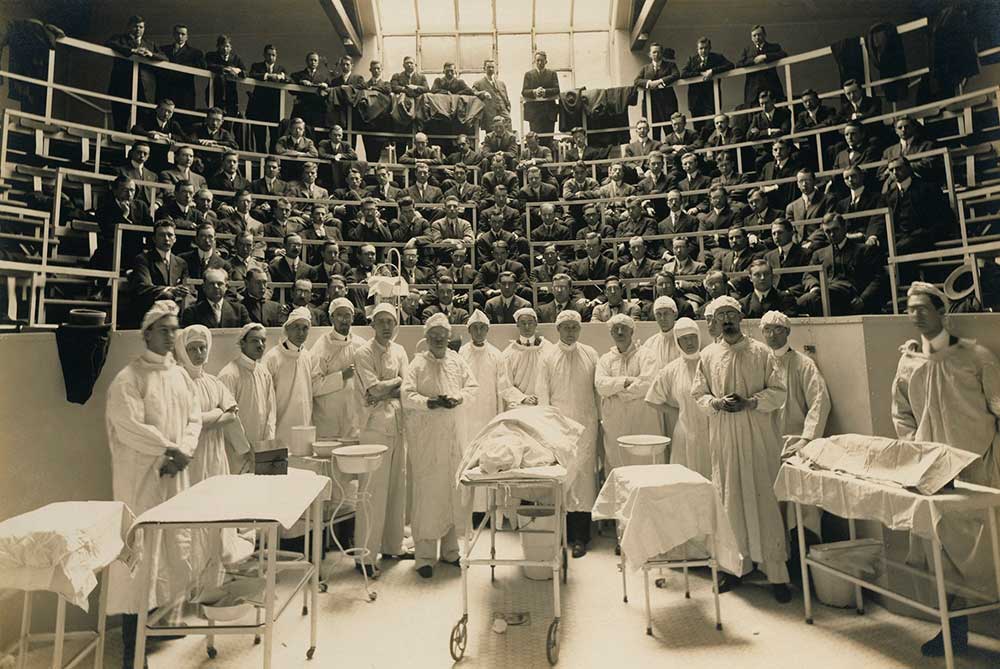

Medical school class and staff with cadaver, c. 1900. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

Brockhurst turned on Swazey with the license that was always permissible.

“Well, what do you know? Now let me try you. Please raise hands, little boys, when you know the answer to these questions, but don’t bluff teacher. I’m not contending you should have a detailed knowledge of the world in your eager, studious minds. I am saying that you haven’t the slightest general information. I’ll make my questions fair.

“First, music: I won’t ask you the tendencies and theories of the modern schools—you won’t know that such a thing as a theory in music exists. You know the opera of Carmen—good old ‘Toreador Song.’ Do you know the name of the composer? One hand—Bob Story. Do you know the history of its reception? Do you know the sources of it? Do you know what Bach’s influence was in the development of music? Did you ever hear of Leoncavallo, Verdi, or that there is such a thing as a Russian composer? Absolute silence. You have a hazy knowledge of Wagner, and you know that Chopin wrote a funeral march. That is your foothold in music; there you balance, surrounded by howling waters of ignorance.

“Take up religion. Do you know anything about Confucius, Shintoism, or Swedenborg, beyond the names? Of course you would not know that under Louis XVI a determined movement was made to reunite the Catholic and Protestant branches, which almost succeeded. That’s unfair, because of course it is the forerunner of the great religious movement today. Do you know the history of the external symbols of the Christian religion, and what is historically new? Darkness denser and denser.

“Take literature. You have excavated a certain amount of Shakespeare and grubbed among Elizabethans and cursed Spenser. Who has read Taine’s History of English Literature, or known in fact who Taine is? Only Bob Story. And yet there is the greatest book on the whole subject; you could abolish the English department and substitute it. Beside Story, who else has had even a fair reading knowledge of any other literature—Russian, Norwegian, German, French, Italian? Who knows enough about any one of these writers to look wise and nod; Renan, Turgenev, Daudet, Bjørnson, Hauptmann, Sudermann, Strindberg? Do you know anything about Goethe as a critic, or the influence of Poe upon French literature? What do you know? I’ll tell you. You know Les Misérables and The Three Musketeers in French literature. You know Goethe wrote Faust. You’re beginning to know Ibsen as a name, and one may have read Tolstoy, and all know that he’s a very old man with a long white beard who lives among his peasants, has some queer ideas, and has started to die three or four times. The papers have told you that.

“Take another field, of simple curiosity on what is doing in a world in which by opportunity you are supposed to be of the leading class. What do you know about the strength and spread of socialism in Germany, France, and England? In the first place, no one of you here probably has any idea of what socialism is; you’ve been told it’s anarchy, and as that only means dynamite to you, you are against socialism and will never take the trouble to investigate it. What do you know about the new political experiments in New Zealand? Nothing. What do you know about the labor pension system in Germany, or the separation of the church and state in France? All subjects dealing with the vital development of the race of bipeds on this earth of which you happen to be members.”

“Help!” cried Hungerford, as Brockhurst went rushing on. “Great Scott, what do we know?”

“You know absolutely nothing,” said Brockhurst savagely. “Here you are; look at yourselves—four years when you ought to learn something, some informing knowledge of all that has developed during the four thousand years the human race has fought its way toward the light, four years to be filled with the marvel and splendor of it all, and you don’t know a thing.

“You have no general knowledge, no intellectual interests, you haven’t even opinions, and at the end of four years of education, you will march up and be handed a degree—bachelor of arts! Magnificent! And we Americans have a sense of humor! Do you wonder why I repeat that our colleges are splendidly organized institutions for the prevention of learning? No, sir, we are business colleges, and the business of our machines is to stamp out so many businessmen a year, running at full speed and in competition with the latest devices in Cambridge and Princeton! The whole theory is wrong, archaic, and ridiculous—the theory of education by schedule. All education can do is to instill the love of knowledge. You get that, you catch the fire of it—you educate yourself. All education does today is to develop the memory at the expense of the imagination. It says: ‘Here are so many pounds of Greek, Latin, mathematics, history, literature. In four years our problem is to pass them through the heads of these hundreds of young barbarians so that they will come out with a lip knowledge.’ ”

“But come, we do learn something,” said Hungerford.

“No, you don’t, Joe,” said Brockhurst. “The main trouble here is, and there is no blinking the fact, that the colleges have surrendered unconsciously a great deal of their power to the growing influence of the social organization. In a period when we have no society in America, families are sending their sons to colleges to place themselves socially. Some of them carry it to an extreme, even directly avow their hope that they will make certain clubs at Princeton or Harvard, or a senior society here. It probably is very hard to control, but it’s going to turn our colleges more and more, as I say, into social clearinghouses. At present here at Yale, we keep down the question of wealth pretty well; fellows like Joe Hungerford here come in and live on our basis. That’s the best feature about Yale today—how it will be in the future I don’t know, for it depends on the wisdom of the parents.”

“Social clearinghouse is well coined,” said Hungerford. “I think it’s truer, though, of Harvard.”

Owen Johnson

From Stover at Yale. After graduating in 1901 from Yale, where he chaired the college literary magazine, Johnson moved to Paris and published his first novel. “It seemed to me that the four years of college was the time when the soul goes through the crucible,” Johnson told an interviewer in 1912. When the interviewer told Johnson that, according to a poll, 86 percent of Yale’s senior class believed Stover at Yale an exaggeration of the college experience, Johnson criticized “this uneducated and unreasoning college loyalty.”