Democracy is the menopause of Western society, the grand climacteric of the body social. Fascism is its middle-aged lust.

—Jean Baudrillard, 1987

A Spiral Amongst Thousands, 2023. Photograph by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope. Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly bravely addresses the hotly contested word freedom. It is hotly contested in part because what the word means has never been clear, a fact that has not seemed to lessen its importance for us. It is a word in which we have invested enormous amounts of energy without producing much in the way of illumination. And yet freedom cannot be dismissed simply on semantic grounds—“just another word,” as Kris Kristofferson sang—because what is at its heart may very well answer the question “What does it mean to be human?”

In our own moment, progressive activists resist what they see as the opposite of freedom: slavery. Modern slavery takes the forms of work and debt, of legislation limiting a woman’s authority over her own body, of racist segregation, and of the prison-industrial complex, to name but a few examples. Our world is not so different from the one described by

Belinda, a woman enslaved for fifty years in eighteenth-century Massachusetts, where “lawless domination sits enthroned, pouring bloody outrage and cruelty on all who dare to be free.”

The voice of economic privilege uses the idea of freedom in order to claim the right to deploy property to its own rich advantage. Making matters worse, others on the political right have weaponized freedom to advance a long list of grievances about what they believe has been wrongly taken from them. Some of these grievances are legitimate; neoliberalism has indeed denied many people the work that once gave them economic independence and a sense of self-worth. But that legitimate complaint has gotten tangled with terrible things, especially the perception of those on the right talking freedom that they have been “replaced” by racial minorities, liberated women, and the LGBTQ community. So they set out to “own the libs” and reclaim their lost freedoms through the public display of their resentments (aka rioting), with guns on their hips if they so choose (and they usually do). This is freedom as understood in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: “War is peace. Slavery is freedom. Ignorance is strength.”

What is missing in all of this is the simple insight of the anarchist

Charlotte Wilson: “We dream of the positive freedom which is essentially one with social feeling: of free scope for the social impulses now distorted and compressed.” For Wilson, freedom is not a thing to be defined. It is something like humanity’s founding metaphysic. As with love or beauty, we don’t know what it is, but we couldn’t get through a day without it. It is like Hegel’s concept of Geist (“spirit”), an intuitive confidence in freedom as a guiding and ongoing human project.

Distorted and compressed though we may still be, Wilson’s anarchist impulse remains with us, as Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio’s 2022 documentary George Carlin’s American Dream has reminded us. The film made me wonder how it was possible for a being like George Carlin to exist at all, and even to thrive in the popular imagination. How was he possible? The answer is simple enough, because it’s not as if Carlin was self-invented. At every stage of his career, he was an expression not only of the 1960s counterculture but of the countercultural imagination as an old and honored social force. For the most part, we know this force as art, following André Breton, Diego Rivera, and Leon Trotsky’s insistence that art is “the natural ally of revolution.” In their Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art, the three write:

To those who urge us, whether for today or for tomorrow, to consent that art should submit to a discipline that we hold to be radically incompatible with its nature, we give a flat refusal, and we repeat our deliberate intention of standing by the formula: complete freedom for art.

In the peculiar moment that was the sixties counterculture, George Carlin was a distillation of what Monty Python called “something completely different.” And yet he became famous not because he was different, but because he was common. He was “one of us, one of us,” as the sideshow performers chanted in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks.

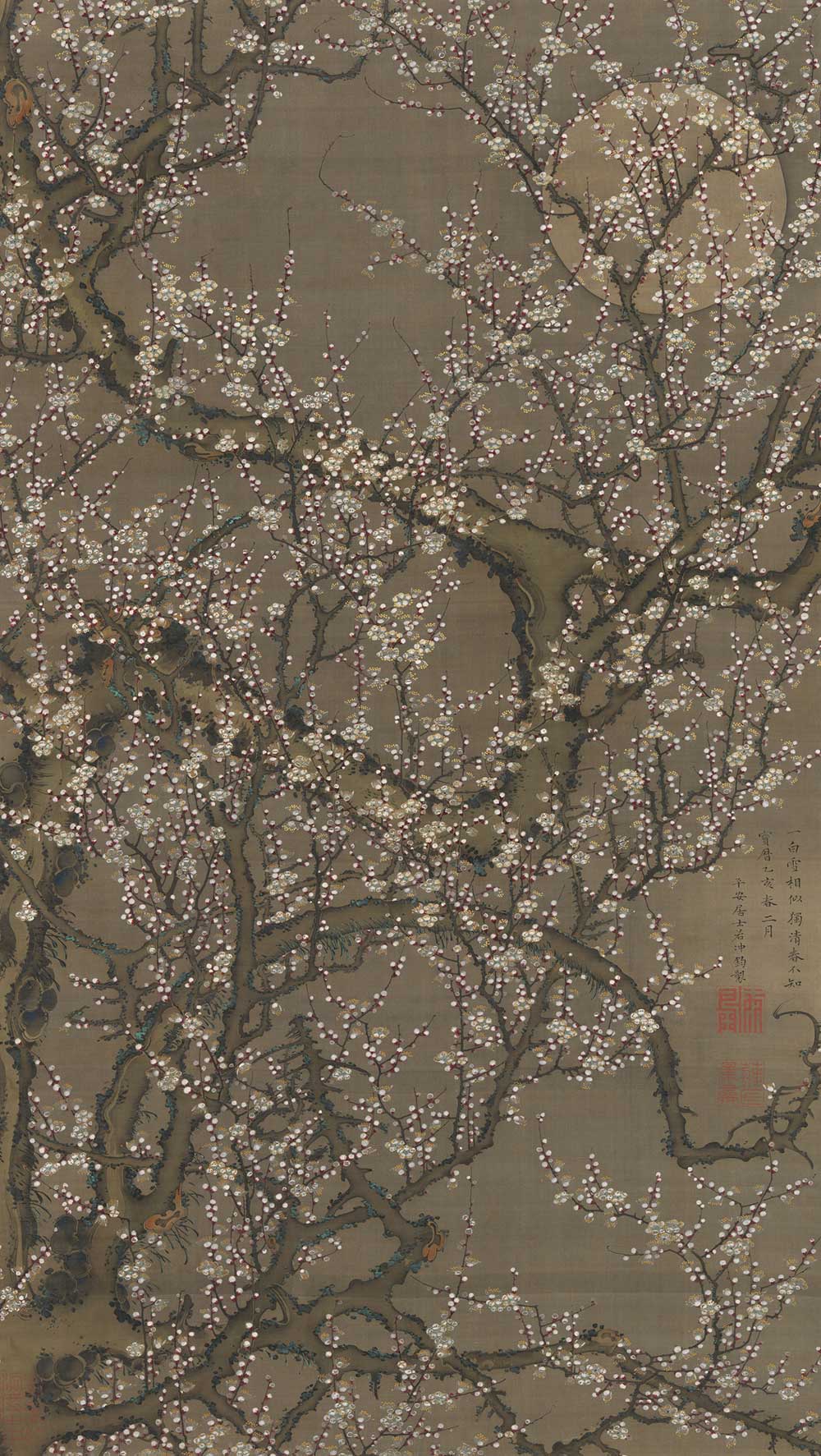

White Plum Blossoms and Moon, by Ito Jakuchu, 1755. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015.

Of course, the sixties counterculture wasn’t self-invented either. It had its American roots in the persona of our founding performance artist,

Mark Twain. In his Autobiography, Twain fearlessly declares of freedom:

There are certain sweet-smelling, sugarcoated lies current in the world which all politic men have apparently tacitly conspired together to support and perpetuate. One of these is that there is such a thing in the world as independence: independence of thought, independence of opinion, independence of action…We are discreet sheep.

Twain had spectacular contemporaries on the American stage: the celebrated lecture tours of Charles Dickens and Oscar Wilde, the latter a dandified counterculturist if ever there was one. Wilde’s notion of freedom, like Carlin’s and Twain’s, was simply the right to be intelligent and original in a world determined to be a collective of dunces:

Art is individualism, and individualism is a disturbing and disintegrating force. Therein lies its immense value. For what it seeks to disturb is monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit, and the reduction of man to the level of a machine.

So that’s how Carlin happened. He was part of a lineage. Apatow and Bonfiglio’s film reminded me of something that was at one time a countercultural given, settled truth if not law, to wit: “The American dream is bullshit.” This meant for Carlin and millions of others that the “pursuit of happiness” in the “land of the free,” accomplished through the freedom to pursue “our own good in our own way,” as John Stuart Mill put it, was a bad joke that more truly meant, as Nietzsche would have said, “You are a herd and you are being led to slaughter.”

George Carlin was the dark bard of American unfreedom.

The primary form that American unfreedom takes is, like Edgar Allan Poe’s purloined letter, hidden in plain sight. It is a thing so common that it disappears into what we take to be the state of nature: money. The prison house of money. As the seventeenth-century Huron chief

Kandiaronk attests in this issue:

I affirm that what you call silver is the devil of devils, the tyrant of the French, the source of all evil, the bane of souls, and the slaughterhouse of the living. To pretend you can live in the country of money and at the same time save one’s soul is as great a contradiction as for a man to go to the bottom of a lake to preserve his life.

Recently, the bounds of the prison house of money have become vividly clear for college students. Whether they study at a university, a college, or an unaccredited vocational school like Trump University, the young have to contend with three raw facts that together form a penal confine. If you want a good job, you will have to go to college; if you go to college, you will have to take on debt; and if you want to pay off your debt, you will have to study what money wants you to study (for the most part, business and the STEM disciplines). In case you miss the point here—and almost everyone does—this is naked social coercion. The only thing that might need to be added is the specter of homelessness, so join a not-so-subtle form of domestic terrorism to the coercion, because the front pages of the daily newspapers make it very clear that there but for fortune go you, with a tent and a sleeping bag, or if you’re one of the lucky, a ’92 Winnebago Chieftain with transmission issues. So you’d better stay in school—whatever the cost.

Through decades of Reaganism and neoliberal austerity, a determination was made by the elite that the state should no longer pay for social infrastructure like education, health care, and affordable housing. Henceforth, social goods would be privatized and then funded through personal debt. College tuition became a bloated user fee, like paying through the nose for a spot in a private parking lot in Manhattan, while incurring the expense of hospitalization became the shortest route to bankruptcy.

Even so, this monstrous situation will continue to be called “freedom of choice,” however much career counselors and personal finance advisers cringe at the idea. Because it is a lie, but it is not a lie without its own rationality. There is an old saying on the left that goes, “Capitalism knows it will have enemies, but if it must have enemies, it will create them itself and in its own image.” Make no mistake: freedom is its enemy, and capitalism is deeply afraid of it. Money offers its own bullying freedom and dares all comers to contest the claim. But unlike Carlin, mostly we don’t dare, because, as Antonio Negri writes, “Money has only one face, that of the boss.”

Karl Marx drew a picture of the prison house of money in Capital, volume one: M—C—Mʹ. Capital in front, profit behind, and the infinite potential of human productivity and play shackled in the middle.

As Fernando Pessoa reminds us, our lives are lived inside social fictions: “I tried to see what was the first and most important of those social fictions…The most important, at least in our day and age, is money.” But money is just part of a much larger complex, what Wilde called “the slavery of custom,” in which we have no choice but to live. As the January 6 insurrection and its aftermath have shown, we tell ourselves stories about patriotism—patriotism with no content other than its own fury. Whether it comes from the rioter in chief, the rioters themselves, or the House members impaneled to investigate them, uncritical love of the nation-state generates unfreedom, violence, and, too often, death, as dear Mother Russia has shown once again, in Ukraine. As John Dos Passos dramatized in The 42nd Parallel, patriotism and the rioting that too often attends it are no new thing, as when a “cordon of cops” sweeps up ideological combatants of left and right: “Look out for the Cossacks.”

Of course, knowing that we live in social fictions and knowing how to escape them are different things. One of the discoveries of the sixties counterculture was that Eastern religions, Buddhism in particular, helped to provide a line of flight. Looked at through a Buddhist lens, what we call social fictions Buddhism calls karma, the causes and conditions into which we are born. In the popular imagination, the Buddhist concept of karma is about personal decisions that create good or bad consequences: the actions of an individual influence the future births of that individual. We say, “Don’t do that, it’s bad karma.” But there is also a karma of the collective. Personal decision-making happens only within a larger karmic context. No one has to go to the trouble of inventing destructive ways of life; they are always already here waiting for every child.

Noblemen of Brabant presenting a petition for religious freedom, detail of an engraving by Frans Hogenberg, c. 1570. Alfredo Dagli Orti/Art Resource, NY.

To be born into a racist/sexist/evangelical/gun-crazy/truck-driving community makes it extremely likely that you will be to some degree a racist/sexist/evangelical/gun-crazy/truck-driving human being. This is “instant karma,” as John Lennon sang. Similarly, being born into the moneyed, privileged world inhabited by Lennon’s “beautiful people” is likely to lead the highborn ones to the assumption that their abundant lives are just how things should be. After all, they’re so pretty, and so much smarter than the rest of us, a claim proved by the size of their bank accounts. Karma is the customs and the habits of mind that we are born into, live through, and then pass on to the next generation. Karma is the bubble we live in, thinking that it is the ocean.

As the sixteenth-century essayist Michel de Montaigne wrote, by way of quoting Pliny the Elder, “Custom is the most powerful master of all things.” Montaigne expands the characterization:

Little by little and stealthily, she establishes within us the footing of her authority; but having, by this mild and humble beginning, stayed and rooted it with the aid of time, she then displays a fierce and tyrannical countenance, in opposition to which we no longer have liberty even to lift up our eyes. We see her do violence constantly to the laws of nature.

Alexander Herzen makes much the same point in “Omnia Mea Mecum Porto”:

People allow the external world to overcome them, to captivate them against their will; they renounce their independence, depending on all occasions not on themselves but on the world, pulling ever tighter the knots that bind them to it. They expect from the world all the good and evil in life; the last thing they rely on is themselves. With such childish submission, the fatal power of the external becomes invincible; to enter into battle with it seems madness. Yet this terrible power wanes from the moment when in a man’s soul, instead of self-sacrifice and despair, instead of fear and submission, there arises the simple question: “Am I really so fettered to my environment in life and death that I have no possibility of freeing myself from it even when I have in fact lost all touch with it, when I want nothing from it and am indifferent to its bounty?”

Herzen’s solution is to remove our fetters through “self-reliance,” a remedy not so far from capitalism’s appeal to economic individualism and the American obsession with self-determination and “going it alone.” Happily, there are other ways of looking at the problem. From a Buddhist perspective, the way out of Herzen’s dilemma is to awaken from the world’s orthodoxies, stop perpetuating the harm of karma/culture, and then go beyond it, into an alternative social reality, the sangha, human community defined not by the suspect freedoms of the ego, His Majesty the Sovereign Self, but by “right understanding” and by metta, kindness.

In a word, Buddhism offers not just critique but counterculture. Robert Thurman explains in Essential Tibetan Buddhism that, almost a millennium before the Chinese invasion of Tibet, Buddhism displaced the warlords and created “a countercultural movement that endured”:

The monastic organization was a kind of inversion of the military organization: a peace army rather than a war army, a self-conquest tradition rather than an other-conquest tradition, a science of inner liberation rather than a science of liberating the outer world from the possession of others.

By creating communities against the grain, Buddhism provides a demystified enlightenment. To whatever degree we can withdraw not from the world but from worldly forms and social fictions, to that degree we are enlightened. Marxist critique finds ways to think outside the deadly platitudes that reign over us, but Buddhism offers more: a place to stand not by our self-reliant selves but with others, in community, where we discover the importance of the bodhisattva vow, which might be summarized as “No one is free until we are all free.”

It is clear enough that George Carlin was a critic of American unfreedom, but what’s not as clear is that he, too, had made a vow to lead us to our essential freedom. This goes a long way toward explaining why his audience wrote to him not mainly with congratulations for a funny act but with gratitude. The task he set himself was difficult: how to offer freedom by performing it, onstage, in the context of that vulgar thing, a stand-up comedy routine. Carlin said some funny things, he said some stupid things, and he said a lot of true things, but in the end it was the totality of the performance, the enactment of freedom, that mattered. Carlin understood that “art is the daughter of freedom,” in Friedrich Schiller’s revealing phrase.

George Carlin’s American Dream is shocking now not because it is saying something new. What is shocking to us is the realization that we have forgotten life-giving things that were once familiar and full of promise. Somewhere along the way, freedom fell into forgetfulness. Again. Carlin was devoted to reminding us of that freedom. He created his sense of it on the stage, and then invited us to join him. Because, as the film’s title implies, George Carlin had his own style of American dreaming.

Freedom from harmful social fictions is important for our shared future. But is “raising consciousness,” as we used to call it, our ultimate freedom? Late in his career Carlin seems to have discovered a freedom beyond freedom. Transcendence, perhaps, but transcendence as improvised on open-mic night at the local comedy club. When Carlin was onstage, he enjoyed the freedom of a dancer, but, as Nietzsche thought, “above the dancer is the flyer and his bliss.”

Consider the first five minutes of George Carlin’s 1996 interview with Charlie Rose. It still drops the jaw even a quarter century after the fact.

I found a very liberating position for myself as an artist. And that was I sort of gave up on the human race and gave up on the American dream, and culture, and nation, and decided that I didn’t care about the outcome. And that gave me a lot of freedom from a kind of distant platform to be sort of amused, kind of to watch the whole thing with a combination of wonder and pity, and try to put that in words…Not having an emotional stake in whether this experiment with human beings works.

Peering with great attention at Charlie Rose, as if he were thinking, “Dig this, Charlie. See if you can chuckle at this,” he continues:

I root for the big comet, I root for the big asteroid to come and make things right…I’m rooting for that big one to come right through that hole in the ozone layer because I want to see it on CNN…Philosophers say, Why are we here? I know why I’m here. The show. Bring it on…We’ve all seen a lot of comedians who seem to have a political bent in their work, and always implicit in the work is some positive outcome, that this is all going to work. If only we do this, if only we pass that bill, if only we elect him. It’s not true.

And then he says, “It’s circling-the-drain time.”

And damned if Charlie Rose doesn’t chuckle, but what Carlin meant was—as he put it in one of his routines—“Pack your shit, folks, we’re going away.” That wouldn’t seem to be funny at all.

Soldier Scene, by Carel de Moor, c. 1700. Rijksmuseum, S. van der Horst bequest, Haarlem.

Not everyone was as pleased as Carlin himself seemed with this sobering turn in his career. Stephen Colbert, for one, thought that Carlin had turned nihilistic. As Colbert comments in American Dream, “To pursue that level of darkness in the hope that it actually would point toward something hopeful is expecting a lot from your audience, because all you’re stating is the dark part.”

But for any Buddhist watching the film, there is something oddly familiar about Carlin’s new perspective. As Greg Gilman comments in a perceptive essay in Los Angeles magazine: “Don’t confuse awareness of the inevitable with nihilism…Comedy at its best is funny because it’s true. The audience relates to the truth of the punch line. But truth can also hurt.” Or as Carlin put it, “One of the problems of Americans is they can’t really face reality. And that’s why, when it comes crashing down, no one is going to be prepared to handle it.” The question that Carlin leaves hanging is “Handle how?”

In Buddhism, the world of individuals who, in Carlin’s word, “clot” into self-destructive groups is called samsara, the world of suffering, dissatisfaction, and change. It is a world that can’t be fixed. It is simply part of “what is,” as Buddhists say, just as the murderous comets whizzing around us are a portion of what is. Comets and clotted people are aspects of the Big Electron, Carlin’s term for “everything that is”: “It doesn’t punish, it doesn’t reward, it doesn’t judge at all, it just is, and so are we, for a little while.” All we can do is practice honesty and hope that through it we can find acceptance of what is and…laughter? Because there is something important in laughter: the possibility of other possibilities. Through laughter Carlin turned audiences into communities. They laughed together. They left the theater open to possibility, even if that sense of freedom was gone by the time they got home. Even so, Carlin’s audience had been offered a “great notion,” in Ken Kesey’s words, and not a bloody “great nation.”

Strangely, what all this reminds me of is the recent infrared images coming to us from the James Webb Space Telescope. Those images convey a reality fourteen billion years in the making. And while we find the Webb images beautiful and moving, they also show us a fundamental truth about “what is”: they show that all things arise, linger, and fall away, including our troubled blue world. The cosmos is on fire, but we have our own little blaze here, the bonfire of the vanities, the flammable passions—greed, anger, and delusion, especially delusion, as neither Carlin nor the Buddha ever tired of showing us.

Pushing someone toward liberty does not set her free; taking the chains off a prisoner does not give him freedom.

—Ken Bugul, 1982When we look at the Webb images, we are not seeing Aristotle’s primum movens immobile, the fixed stars, the unmoved heavens ever available for our gazing. The universe has been expanding and accelerating at 163,000-plus miles per hour for the past fourteen billion years; it is very much on the move. Eventually, this acceleration, red factor flashing, will reach a point where no light will be able to reach us from outside the gravitational confines of our own galaxy. But even this idea is a delusion because in a mere one billion years Earth will be just another star-baked cinder, torched by our expanding sun, and there won’t be anyone here to wonder where all the stars have gone.

Is that too dark, Stephen Colbert?

Carlin claimed that imagining the end of the world was entertaining. But perhaps it is better to think that not caring how it turns out is comic hyperbole for the “peace that surpasses all understanding.” Carlin’s view isn’t much different from that of

Vivekananda, who wrote in 1893:

There is only one way to attain that freedom which is the goal of all the noblest aspirations of mankind, and that is by giving up this little life, giving up this little universe, giving up this earth, giving up heaven, giving up the body, giving up the mind, giving up everything that is limited and conditioned.

The teachings of the Buddha and the comedy of George Carlin are founded on a common perception: things are not the way they seem. Our world may seem hard, durable, and permanent, but it is not. That truth can be alarming, especially when delivered by a wit as caustic as Carlin’s, but it can also be funny, as funny as the emperor’s discovery that his new clothes are his own nakedness, his gaudy social fictions stripped away, leaving only his mortality. At its best, a joke’s punch line is secular kensho, sudden enlightenment, a moment in which we briefly awaken to how things really are and laugh. What may not be so clear is that this laughter is a summons not only to freedom but to spiritual liberation.