Oh, tell me, who was it first announced, who was it first proclaimed, that man does nasty things only because he does not know his own interests; and that if he were enlightened, if his eyes were opened to his real, normal interests, man would at once cease to do nasty things, would at once become good and noble because, being enlightened and understanding his real advantage, he would see his own advantage in the good and nothing else? Oh, the babe! Oh, the pure, innocent child!

What if it so happens that a man’s advantage sometimes not only may, but even must, consist in his desiring in certain cases what is harmful to himself and not advantageous? And if so, if there can be such a case, the whole principle falls into dust. What do you think—are there such cases? You laugh; laugh away, gentlemen, but only answer me: Have man’s advantages been reckoned up with perfect certainty? Are there not some that not only have not been included but cannot possibly be included under any classification? You see, you gentlemen have, to the best of my knowledge, taken your whole register of human advantages from the averages of statistical figures and politico-economical formulas. Your advantages are prosperity, wealth, freedom, peace—and so on, and so on. So that the man who should, for instance, go openly and knowingly in opposition to all that list would to your thinking—and indeed mine, too, of course—be an obscurantist or an absolute madman. Would not he? But, you know, this is what is surprising: Why does it so happen that all these statisticians, sages, and lovers of humanity, when they reckon up human advantages, invariably leave out one? They don’t even take it into their reckoning in the form in which it should be taken, and the whole reckoning depends upon that. It would be no greater matter; they would simply have to take it, this advantage, and add it to the list. But the trouble is that this strange advantage does not fall under any classification and does not have a place on any list. This advantage is remarkable for the very fact that it breaks down all our classifications, and continually shatters every system constructed by lovers of mankind for the benefit of mankind. In fact, it upsets everything. Before I mention this advantage to you, I want to compromise myself personally, and therefore I boldly declare that all these fine systems—all these theories for explaining to mankind their real, normal interests, in order that inevitably striving to pursue these interests they may at once become good and noble—are, in my opinion, so far mere logical exercises. Only look about you: blood is being spilled in streams, and in the merriest way, as though it were champagne. Take Napoleon—the Great and also the present one. Take North America—the eternal Union. Take the farce of Schleswig-Holstein. Have you noticed that it is the most civilized gentlemen who have been the subtlest slaughterers, to whom the Attilas and Stenka Razins could not hold a candle, and if they are not so conspicuous as the Attilas and Stenka Razins it is simply because they are so often met with, are so ordinary, and have become so familiar to us. In any case civilization has made mankind if not more bloodthirsty at least more vilely, more loathsomely bloodthirsty. In old days he saw justice in bloodshed and with his conscience at peace exterminated those he thought proper. Now we do think bloodshed abominable, and yet we engage in this abomination—and with more energy than ever. Which is worse? Decide that for yourselves. They say that Cleopatra (excuse an instance from Roman history) was fond of sticking gold pins into her slave-girls’ breasts and derived gratification from their screams and writhings. You will say that that was in the comparatively barbarous times; that these are barbarous times, too, because, comparatively speaking, pins are stuck in even now; that though man has now learned to see more clearly than in barbarous ages, he is still far from having learned to act as reason and science would dictate. But yet you are fully convinced that he will be sure to learn when he gets rid of certain old bad habits, and when common sense and science have completely reeducated human nature and turned it in a normal direction. You are confident that then man will cease from intentional error and will, so to say, be compelled not to want to set his will against his normal interests. That is not all; then, you say, science itself will teach man (though to my mind it’s a superfluous luxury) that he never has really had any caprice or will of his own, and that he himself is something of the nature of a piano key or the stop of an organ, and that there are, besides, things called the laws of nature, so that everything he does is not done by his willing it but is done of itself, by the laws of nature. Consequently we have only to discover these laws of nature, and man will no longer have to answer for his actions and life will become exceedingly easy for him.

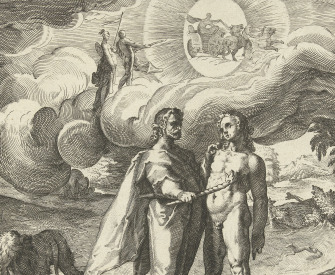

Moses and Pharaoh’s Crown, by Jan Steen, 1670. Mauritshuis, The Hague, acquired with the support of the VriendenLoterij, 2011.

In fact, those will be halcyon days. Of course there is no guaranteeing (this is my comment) that it will not be, for instance, frightfully dull then (for what will one have to do when everything will be calculated and tabulated?), but on the other hand everything will be extraordinarily rational. Of course boredom may lead you to anything. It is boredom that sets one sticking golden pins into people, but all that would not matter. What is bad (this is my comment again) is that I dare say people will be thankful for the gold pins then. Man is stupid, you know, phenomenally stupid; or rather he is not at all stupid, but he is so ungrateful that you could not find another like him in all creation. I, for instance, would not be in the least surprised if all of a sudden, apropos of nothing, in the midst of general prosperity a gentleman with an ignoble, or rather with a reactionary and ironical, countenance were to arise and, putting his arms akimbo, say to us all: “I say, gentlemen, hadn’t we better kick over the whole show and scatter rationalism to the winds simply to send these logarithms to the devil and to enable us to live once more at our own sweet foolish will!” That again would not matter, but what is annoying is that he would be sure to find followers—such is the nature of man. And all that for the most foolish reason, which, one would think, was hardly worth mentioning: that is, that man everywhere and at all times, whoever he may be, has preferred to act as he chose and not in the least as his reason and advantage dictated. And one may choose what is contrary to one’s own interests, and sometimes one positively ought (that is my idea). One’s own free, unfettered choice, one’s own caprice, however wild it may be, one’s own fancy worked up at times to frenzy is that very “most advantageous advantage” that we have overlooked, which comes under no classification and against which all systems and theories are continually being shattered to atoms. And how do these wiseacres know that man wants a normal, a virtuous choice? What has made them conceive that man must want a rationally advantageous choice? What man wants is simply independent choice, whatever that independence may cost and wherever it may lead. And choice, of course, the devil only knows what choice.

From Notes from Underground. In 1859, after returning to St. Petersburg from his exile in Siberia, Dostoevsky began working as an editor at the journal Vremya. In 1863 Nikolay Chernyshevsky published the novel What Is to Be Done?, which called for Russian society to be radically reformed by heroic individuals and depicted the imposing Crystal Palace as a future utopia. Dostoevsky wrote Notes from Underground partly as a response to Chernyshevsky’s novel, rejecting its utilitarian vision of replacing moral standards with reason and progress.

Back to Issue