History is a people’s memory, and without a memory man is demoted to the level of the lower animals.

—Malcolm X, 1964Mitch Landrieu Takes History Off a Pedestal

Revising how America remembers its past.

The soul of our beloved city is deeply rooted in a history that has evolved over thousands of years; rooted in a diverse people who have been here together every step of the way—for both good and for ill.

It is a history that holds in its heart the stories of Native Americans—the Choctaw, Houma Nation, the Chitimacha. Of Hernando de Soto, Robert Cavelier de La Salle, the Acadians, the Isleño, the enslaved people from Senegambia, free people of color, the Haitians, the Germans, both the empires of France and Spain. The Italians, the Irish, the Cubans, the South and Central Americans, the Vietnamese, and so many more.

You see, New Orleans is truly a city of many nations, a melting pot, a bubbling cauldron of many cultures. There is no other place quite like it in the world that so eloquently exemplifies the uniquely American motto e pluribus unum—out of many we are one.

But there are also other truths about our city that we must confront. New Orleans was America’s largest slave market: a port where hundreds of thousands of souls were bought, sold, and shipped up the Mississippi River to lives of forced labor, of misery, of rape, of torture.

America was the place where nearly four thousand of our fellow citizens were lynched, 540 in Louisiana alone; where the courts enshrined “separate but equal”; where Freedom Riders coming to New Orleans were beaten to a bloody pulp.

So when people say to me that Confederate monuments are history, well, what I just described is real history as well, and it is the searing truth. And it immediately begs the questions of why there are no slave-ship monuments, no prominent markers on public land to remember the lynchings or the slave blocks; nothing to remember this long chapter of our lives; the pain, the sacrifice, the shame…all of it happening on the soil of New Orleans.

So for those self-appointed defenders of history and the monuments, they are eerily silent on what amounts to this historical malfeasance, a lie by omission.

There is a difference between remembrance of history and reverence of it. For America and New Orleans, it has been a long, winding road, marked by great tragedy and great triumph. But we cannot be afraid of our truth.

The Sphinx, by Maxime Du Camp, 1849. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005.

So today I want to speak about why we chose to remove these four monuments to the lost cause of the Confederacy, but also how and why this process can move us toward healing and understanding of each other.

So let’s start with the facts.

The historic record is clear, the Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and P.G.T. Beauregard statues were not erected just to honor these men, but as part of the movement that became known as the “Cult of the Lost Cause.” This “cult” had one goal—through monuments and through other means—to rewrite history to hide the truth, which is that the Confederacy was on the wrong side of humanity.

First erected over 166 years after the founding of our city and nineteen years after the end of the Civil War, the monuments that we took down were meant to rebrand the history of our city and the ideals of a defeated Confederacy.

It is self-evident that these men did not fight for the United States of America, they fought against it. They may have been warriors, but in this cause they were not patriots.

These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy, ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.

After the Civil War, these statues were a part of that terrorism as much as a burning cross on someone’s lawn; they were erected purposefully to send a strong message to all who walked in their shadows about who was still in charge in this city.

Should you have further doubt about the true goals of the Confederacy, in the very weeks before the war broke out, the vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, made it clear that the Confederate cause was about maintaining slavery and white supremacy.

He said in his now famous “Cornerstone Speech” that the Confederacy’s “cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the Negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first in the history of the world based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

Now, with these shocking words still ringing in your ears, I want to try to gently peel from your hands the grip on a false narrative of our history that I think weakens us and make straight a wrong turn we made many years ago—so we can more closely connect with integrity to the founding principles of our nation and forge a clearer and straighter path toward a better city and a more perfect union.

As clear as it is for me today, for a long time, even though I grew up in one of New Orleans’s most diverse neighborhoods, even with my family’s long, proud history of fighting for civil rights, I must have passed by those monuments a million times without giving them a second thought.

So I am not judging anybody. I am not judging people. We all take our own journey on race. I just hope people listen like I did when a friend asked me to think about all the people who have left New Orleans because of our exclusionary attitudes.

Another friend asked me to consider these four monuments from the perspective of an African American mother or father trying to explain to their fifth-grade daughter who Robert E. Lee is and why he stands atop of our beautiful city.

Can you do it?

Can you look into that young girl’s eyes and convince her that Robert E. Lee is there to encourage her? Do you think she will feel inspired and hopeful by that story? Do these monuments help her see a future with limitless potential? Have you ever thought that if her potential is limited, yours and mine are too?

We all know the answer to these very simple questions. When you look into this child’s eyes is the moment when the searing truth comes into focus for us. This is the moment when we know what is right and what we must do. We can’t walk away from this truth.

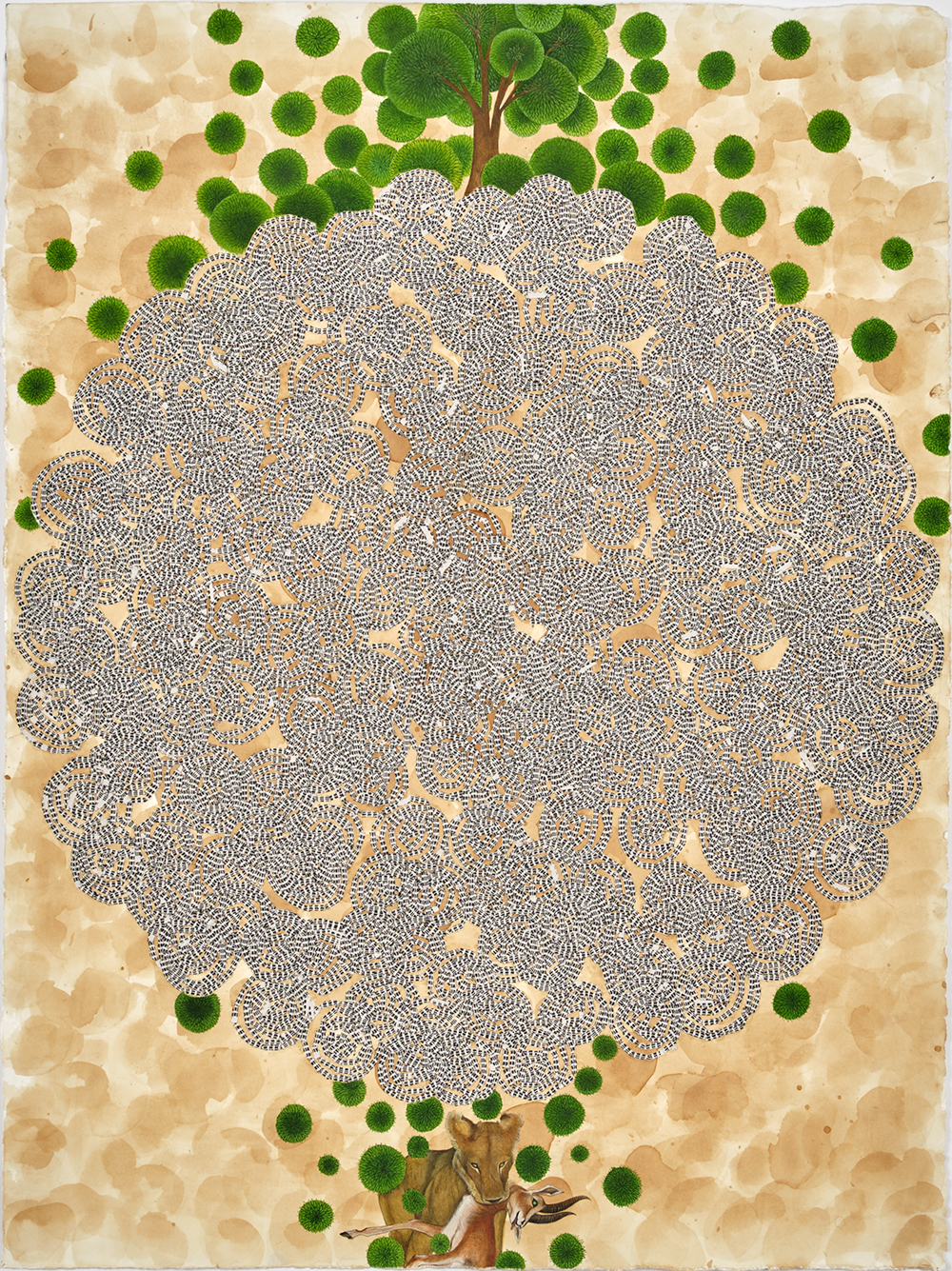

Asadullah (9), by Ambreen Butt, 2019. Watercolor and collage of text on tea-stained paper, 29 x 21 inches. © Ambreen Butt, courtesy the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

And I knew that taking down the monuments was going to be tough, but you elected me to do the right thing, not the easy thing, and this is what that looks like.

So relocating these Confederate monuments is not about taking something away from someone else. This is not about politics, this is not about blame or retaliation. This is not a naive quest to solve all our problems at once.

This is, however, about showing the whole world that we as a city and as a people are able to acknowledge, understand, reconcile, and, most importantly, choose a better future for ourselves, making straight what has been crooked and making right what was wrong. Otherwise, we will continue to pay a price with discord, with division, and, yes, with violence.

The Confederacy was on the wrong side of history and humanity. It sought to tear apart our nation and subjugate our fellow Americans to slavery. This is the history we should never forget and one that we should never again put on a pedestal to be revered.

Mitch Landrieu

From a speech. Mayor of New Orleans from 2010 to 2018, Landrieu gave this speech in Gallier Hall on May 19, hours before workers removed the last of the city’s four Confederate monuments, a statue of Robert E. Lee. Moving the statue from its pedestal on Lee Circle required the use of a heavy crane; every contractor in the region had received threats from the statue’s defenders. A crane was secured only after it was agreed that the identities of the company and its workers would be concealed. In a final, unsuccessful effort to thwart the removal, protestors poured sand in the crane’s gas tank and launched drones at the contractors.