Do not fear the clatter of wheels, the bumps and slops in corridors. It is only turbulence.

—Romalyn Ante, 2020Doctors Without Borders

On the Black doctors who received their medical degrees and a new sort of freedom in Europe.

By Deirdre Mask

Photograph of an African American doctor, exhibited at the Paris Exposition Universelle by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1900. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1954 twenty-six-year-old Beny Primm walked into the registrar’s office of the University of Geneva and willed himself to cry. More than a year before, Primm had stepped off the Queen Mary at Cherbourg, wearing a seersucker suit. He was determined to enroll in medical school in Europe. This office in Switzerland was his last chance.

Growing up along the Tug Fork River in West Virginia, Primm idolized the physician who made house calls on horseback. (“The kids used to throw rocks at cats and dogs,” Primm recalled years later in an interview, “but not at the doctors’ dogs.”) So when imaginary accidents struck the residents of the city Primm and his brother, Gerome, had invented, Primm would doctor the survivors. Gerome buried the rest. Gerome grew up to be a mortician. Primm decided to go to medical school.

But how? In the 1950s only Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, DC, and Meharry Medical College in Nashville admitted African Americans in significant numbers. Together they could graduate only about a hundred students a year. Primm’s childhood friend Alexander Jordan had followed Jewish friends to Europe to study. “You’ve had German,” Jordan told Primm, who had taken the language in college. “Apply to the German medical schools.”

So he did. First stop: University of Heidelberg. But Primm, who had spent three years in the army stationed at Fort Bragg, couldn’t use GI Bill money in Germany, and his army retirement pay wasn’t enough to bring his wife over. Next stop: the Netherlands. The Dutch deputy minister of education, convinced by the badge on Primm’s army coat that he had been one of the paratroopers who had freed the minister’s hometown, admitted him and said he would do fine. The minister was wrong on both counts. Primm had trained as a paratrooper, but Black soldiers were not allowed to serve as paratroopers in combat until after the war. And Primm didn’t do fine in the Netherlands. Dutch was just too difficult. Swiss German in Basel, where he went next, was no easier.

“I said, All right, what the hell am I doing here?” Primm remembered thinking. He called his childhood friend, who told him to try Geneva. So he did.

Charles Wilson, a Black American medical student, took him to see the registrar. “He says, ‘You’ll see me, I’ll give you the sign, and you start to cry.’ He says, ‘Beny, you’ve got to do this.’ ”

Mademoiselle Grosselin, the registrar, noticed Primm tearing up at just the right time. (Grosselin, Primm later found out, had dated a “Moor” and perhaps understood racism better than most in Switzerland.) “You have a good background,” he recounted her saying. “You were a soldier, a paratrooper. We’re going to admit you. I don’t know how you’re going to make it, but I think you’ll make it.”

Ten years before Primm arrived in Europe, Dr. Midian Othello Bousfield, the first Black colonel in the Army Medical Corps, gave a talk at the New York Academy of Medicine in East Harlem on the state of the profession. “There seem to be three problem groups in medicine: Jews, women, and Negroes, and the greatest of these is Negroes,” he told the audience. And yet even before the Civil War, he said, Black people had found creative ways to learn medicine. A 1740 Pennsylvania newspaper advertisement reported a runaway slave named Simon who could “bleed and draw teeth, pretending to be a great doctor.” Not long after, the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly freed two doctors, Caesar and Sampson, but only on the condition that they reveal their antidotes for rattlesnake bites. James Derham, the first Black doctor to practice medicine formally in the U.S., was trained as a surgeon by the physicians who enslaved him in Philadelphia and New Orleans.

The end of the Civil War, Dr. Bousfield continued, “had given colored physicians every reason to believe that they were well on their way to successful careers.” But, unsurprisingly, those hopes were foiled. “They sought memberships in organized medical societies only to find that they were to be met by an emotional opposition of white doctors as fierce, as determined, and as well organized as were the armies in the recently ended war.”

Largely excluded from white universities, students turned to the dozen or so Black medical schools that had sprung up to offer an alternative. One of the most prestigious was Leonard Medical School in Raleigh, North Carolina. Its founders, Henry Martin Tupper and his wife, Sarah, white Baptists from Massachusetts, had purchased the first two train tickets into Raleigh when the tracks were rebuilt after the war. (Not long after, they spent a night in a cornfield when the Ku Klux Klan threatened to burn down their cabin.) Learning there was no medical school for Black people between Washington and New Orleans, Tupper, who had already founded Shaw University, started Leonard Medical School with six thousand dollars from Sarah’s brother, Connecticut businessman Judson Wade Leonard. Shaw students dug red clay and kilned the bricks for the rising buildings.

Many Leonard students thrived. “What does it mean,” one state examiner asked, “that the colored young men are passing a better examination than the white young doctors?” Others lacked the basic education they needed to have a chance; even as late as 1910, only 3 percent of Black children in the South had ever attended high school. “Bad English and spelling,” a faculty report read of one student. “Poor education—no foundation,” said another. “Too ignorant of grammar, spelling, pronunciation to have a diploma.” Leonard became the first American medical school, Black or white, to require a four-year degree, in part to allow ample opportunity to remedy students’ poor academic foundations.

Tupper died in 1893, and the school’s finances, always terrible, somehow managed to get even worse. Even students who missed school for spring plantings and fall harvests and worked through the summer on Pullman cars or waiting tables could often barely cobble together tuition, which was half that of the white schools. At the opening of one school year, the new dean wrote that the medical rooms were “cold, damp, dark firetraps” unconnected to the sewer lines.

Leonard’s coup de grâce came from an unlikely source: a former teacher from Louisville, Kentucky. Abraham Flexner had, by all accounts, never actually set foot in a medical school. But he had founded his own experimental school and studied philosophy at Harvard, later writing a searing critique of American colleges. It was on this résumé that the Carnegie Foundation hired him to conduct a review of medical education. Zipping around the country on train, horse, buggy, and a Ford Model T, Flexner visited all 155 American and Canadian medical schools in 1909 and 1910.

Well-equipped laboratories, affiliations with teaching hospitals, and a wide range of experienced faculty—all these and more Flexner demanded of American medical schools Black and white. Schools like Leonard had the aspirations but not the means; with no endowment, Leonard could not be Johns Hopkins. “A philanthropic enterprise that has been operating for well-nigh thirty years and has nothing in the way of plant to show for it” summed up Flexner’s view of Leonard. Of the Black medical schools, only Howard (whose funding came, in part, from the federal government) and Meharry (whose fundraisers had been more successful), Flexner said, deserved to survive.

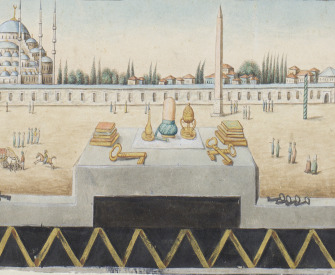

Detail of a scene from a fifteenth-century handscroll of Cai Yan’s Eighteen Verses Sung to a Tatar Reed Whistle. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ex coll.: C.C. Wang Family, gift of the Dillon Fund, 1973.

Flexner assumed that white doctors would care for Black patients if there weren’t enough Black doctors. They didn’t. But even worse, he didn’t just criticize the Black schools—he imagined a new role for the Black doctor, one as a sanitarian rather than a surgeon. “The Negro has his rights and due and value as an individual,” Flexner wrote, “but he has, besides, the tremendous importance that belongs to a potential source of infection and contagion.” And infection could not be segregated as easily as schools and water fountains. “The Negro,” he concluded, “must be educated not only for his sake but for ours.” If it wasn’t already clear whom Flexner was speaking to, the “ours” said it all.

Obvious solutions—like asking white schools to open their doors to Black students—seemed beyond Flexner’s imagination. Later he would champion the remaining Black medical schools, leading Meharry’s capital campaign in the 1940s. But the Carnegie Foundation, which had funded Flexner’s report, refused assistance to Black medical schools, believing the needs were too enormous. “If we start helping medical colleges for colored people,” Andrew Carnegie wrote in a 1914 letter, “we cannot discontinue.”

But Leonard’s poor finances probably doomed the school long before Flexner came to Raleigh. Leonard shut in 1918, as did five other Black medical schools in the years after the report. (Dozens of “white” medical schools closed as well.) By 1920 almost 90 percent of new Black doctors were trained at the only two Black medical schools Flexner deemed worthy: Howard and Meharry.

Ten years later the New York Amsterdam News reported that “every year more and more Negro men are leaving the United States for Scotland and France for the purpose of studying medicine.” The pathway out of segregation led not just north by train but also east, by boat.

“Between me and the other world,” W.E.B. Du Bois opened The Souls of Black Folk, “there is ever an unasked question…‘How does it feel to be a problem?’ ” Being Black in America meant always being a problem—“a strange experience—peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe.” Babyhood and Europe—the only two places where Du Bois did not feel a problem. Europe was the only one of these two places he could still go.

Nina Simone and Josephine Baker, James Baldwin and Richard Wright—singers and writers are the kinds of Black Americans we think of crossing the ocean. This isn’t exactly wrong; after Black soldiers introduced jazz to Europe in World War I, Black musicians crossed the ocean “as if,” the Chicago Defender reported, “they were merely making trips back and forth to Harlem on the subway.” The Black jazz performers who traveled to Europe, historian Rachel Anne Gillett has written, transformed the Atlantic from a slave passage to “an entry point into international success.” And international it was: bands traveled to every capital in Europe, including Moscow, and then skipped over to North Africa and India. Singer Ada “Bricktop” Smith couldn’t believe her luck when she landed in Paris in 1924; to her Europe meant “you had money—unless you were one of those eccentric writers.”

“Eccentric” Black writers had been heading to Europe for hundreds of years. Frederick Douglass spent four months touring in Ireland in 1845. “I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country,” he wrote home. “I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life.” The poet Phillis Wheatley sailed to London in 1773, supported there by a variety of “curious” members of the English aristocracy and visited by Benjamin Franklin. On a six-month reading tour of England in 1897, poet and novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote, “It would be an inestimable blessing if a number of Negroes from every state in the union could live abroad for a few years, long enough to cool in their blood the fever heat of strife.”

Those who go overseas find a change of climate, not a change of soul.

—Horace, 20 BCBy 1936 the New York Times pointed out that “Negro Americans” were increasingly taking to the “crowded travel lanes leading to Europe.” Wealthy Black families returned from grand tours, one commentator wrote, with “not only many new and happy impressions but also a considerable amount of information in the art of living that they do not have the opportunity to get at home.”

But perhaps above all, it was Black intellectuals who made Europe their pilgrimage. Du Bois went to Germany in 1892 after finishing his degree at Harvard College not because of his race but because of the intellectual opportunity. “Any American scholar who wanted preferment,” he said, “went to Germany for study.” Langston Hughes’ father urged him to go to Switzerland for college and learn French, German, and Italian all at once. (Hughes went to Harlem instead, though later he would try his hand at filmmaking in Russia.) Black newspapers reported how French universities were “open for business”; in 1955 James Baldwin estimated five hundred Black Americans were walking the streets of Paris “studying everything from the Sorbonne’s standard Cours de Civilisation Française to abnormal psychology, brain surgery, music, fine arts, and literature.”

Another “problem group” for medical schools, Jewish students, had long looked to Europe for an education. (The dean of the Yale School of Medicine in the 1920s instructed his admission committee, “Never admit more than five Jews, take only two Italian Catholics, and take no blacks at all.”) Officials from medical schools in Michigan and Alabama complained that if they admitted all the qualified Jewish students, the school would be so full of “undesirables” that there would be no room for local students. In 1932 almost two thousand American Jewish students were studying medicine in Europe, mostly in the UK, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland.

Black Americans followed, particularly after World War II. (Others had traveled the path long before. James McCune Smith, the first African American to earn a medical degree, had done so in Scotland in 1837. Black women, too, made the trip; Sarah Parker Remond, born in 1826, studied obstetrics in Florence and practiced in Italy for over twenty years.) It was a win-win situation for the students and the countries that accepted them. A 1932 Philadelphia Tribune article titled “French Universities Would Welcome U.S. Negro Students” quoted an official French report on the rising number of American students in the country: “They return to their country and are excellent missionaries for our ideas, our books, our surgical instruments, our pharmaceutical products and health centers.”

How many decided to strike their course across the ocean is impossible to say; the universities I contacted did not keep records of students’ races. Primm noted that there were eight other Black students on his course in Geneva, seven from the United States. And even a quick search came up with more than a dozen examples of Black medical students traveling abroad in the postwar years, and evidence of many more. In 1954, for example, the graduates of the first degree-granting Black university in the U.S., Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania, were headed to medical schools in Geneva, Beirut, and Amsterdam. “Long confined principally to Howard and Meharry,” a newspaper reported, “Lincoln graduates have within the past ten years been admitted to eighteen different American and eight foreign medical schools.”

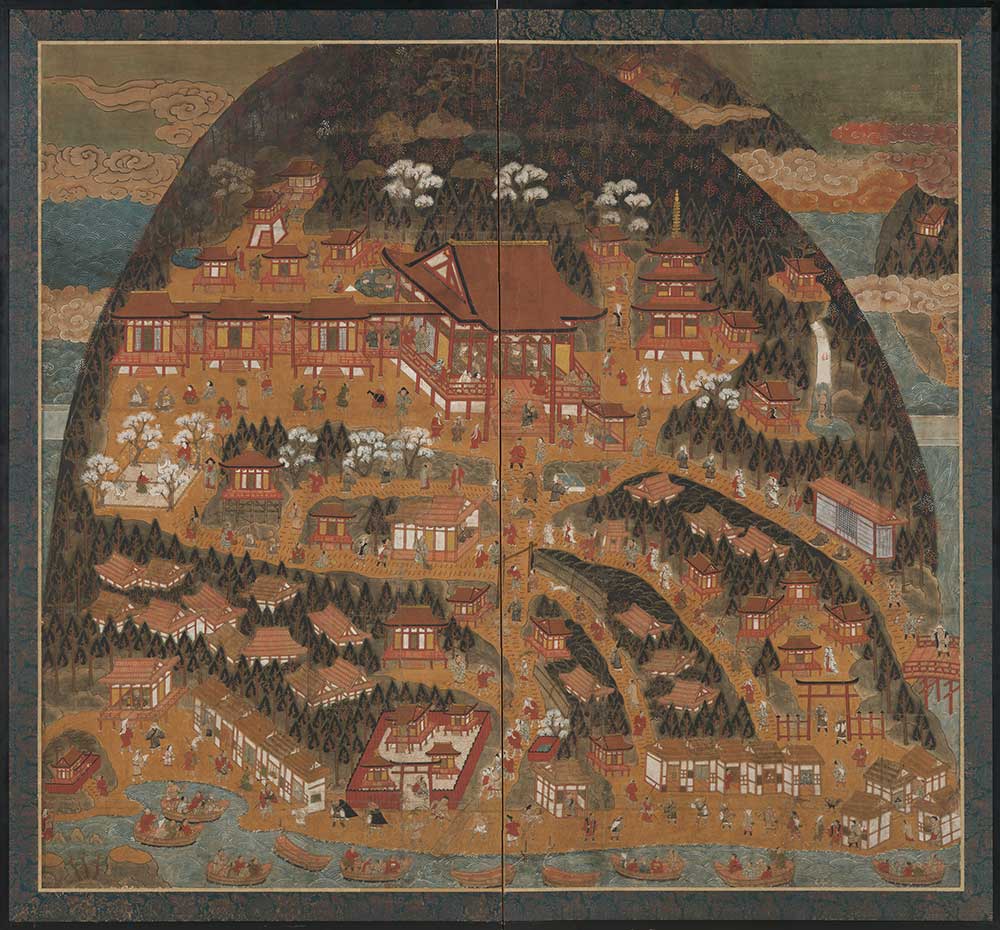

Chomeiji Temple pilgrimage mandala, Japan, c. 1630. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Sue Cassidy Clark gift, in honor of D. Max Moerman, 2016.

Black students going abroad included Beny Primm, who did indeed make it in Geneva, as the registrar had predicted. In fact, he more than made it, returning home to pioneer medical advances in addiction treatment and AIDS prevention. His time in Geneva was all he thought it would be. His wife, Delphine, enrolled in the school of music. His daughter Annelle, now a prominent doctor herself, was the second Black baby born in the hospital; Delphine was named Mother of the Year by a Swiss newspaper. Annelle told me how her father spent time in an externship in an English fishing village, where he was moved by the residents’ struggles, the terrible injuries lashed upon them by the sea, and the way they saw him as a healer, “not simply a ‘Negro’ to be discounted because of his racial identity.” It was no surprise, she told me, that he ended up dedicating his career to public health.

And there was Charles Wilson, the friend who had urged Primm to cry in that registrar’s office. Wilson was an orphan, raised by his grandmother, who went to Hampton Institute in Virginia. During the war he had noticed how the Nazi prisoners were allowed in a Pullman train car—with elegant dining and pullout beds—while the Black soldiers slept sitting up in the segregated cabins. He soon abandoned his lucrative job marketing Pepsi to Black consumers for a chance to become a doctor in Switzerland. The woman he loved arrived in Switzerland soon after him; the banns were read in the square, and they were married. Money was tight (“How many words can you type a minute?” he asked his fiancée soon after she debarked from the boat), but they squeaked by. When their daughter, Medina, was born, she had a Swiss nanny and spoke French. They all learned to swim and ski. In Switzerland, Medina told me, her dad felt like a person.

Black people were accepted in European medical schools—but that didn’t mean that they didn’t stand out. While they made local friends, they were often objects of curiosity and unwanted attention. The Black wife of one medical student in Belgium told me how often she was stared at—“Stop and take a really good look,” her husband would say to passersby. She learned French and hosted literary salons. Yet when they went to visit apartments, the landlords, assuming they were used to huts, told them they might be dizzy if they took a flat on a high floor.

They were from Manhattan.

My great uncle George Mask grew up in Hamlet, North Carolina, a railroad town whose name gives away its small size. George was an unlikely person to finish a medical degree in Germany. He and his brothers and their father before them all went to Saint Augustine’s College in Raleigh, North Carolina, a largely Black university founded by the Episcopal Church. If George had been twenty-five years older, he could have walked across Raleigh to Leonard Medical School. But Leonard was long closed by the time he finished college.

So instead George also crossed the ocean to study medicine at the Universities of Fribourg and Zurich. (His dissertation was titled “Klinischer Beitrag zum Wallenberg-Syndrom,” or “Clinical Contributions to Wallenberg Syndrome.”) George was the ultimate cosmopolitan, fluent in German and French, and a concert-level pianist. He delivered his first baby in Paris; the baby’s parents were thrilled, thinking it lucky for their baby to be born into Black hands. On his flight home from Europe, the pilot was so impressed with the Black doctor that George sat in the cockpit the entire trip. After more training in New York, he became a popular physician, one who made house calls and ran a practice for Brooklynites out of a medical office in his home on Maple Street.

Not that it was easy. Recently, while visiting my grandparents’ house in Hamlet, I found a letter George had written to his brother, my grandfather, from Geneva. The letter spoke of George’s life in Switzerland: the little time he had between classes to go home and make lunch, how he seldom ate in cafés, his time in the “Klinik.” But he quickly got past the small talk to his debts and the meals he had to skip because of them. His father, a school principal, helped support him—but there was only so much he could ask. Could his brothers send twenty or twenty-five dollars? “Even if I didn’t get any money from you two, you might write a line sometimes…You know one is also in need of moral support, too, and the going ain’t easy.”

But was easy what he would have wanted? For me, my uncle’s story, albeit glamorous, has always been one of resistance, of finding a Jim Crow loophole—and enough will to sneak through it. But perhaps it was really an adventure tale. White Americans wanted travel, language, art, skiing, good bread, and fine wine, all alongside a world-class education—why could Black people not also yearn for these things? Why could they not also ask for Europe? The Black students who crossed an ocean for medical school may have been pushed, but perhaps the pull was just as strong.