Can you take your country with you on the soles of your shoes?

—Georg Büchner, 1835Seeds of Expansion

Bernard De Voto visits the edge of an empire.

History does not tell us whether Eric the Red and his successors traded with Indians for furs. If they got to Minnesota, as the legends say, they had to when the winter closed in.

Besides strange birds and herbs and carvings, there may have been furs in the wealth that the Admiral of the Ocean piled in Queen Isabella’s throne room. Certainly, before Spain or France or England sent explorers up the tidal rivers, coasting fishermen from overseas made deals for furs with the native savages. Furs were a principal object of all explorations, no matter if one also sought Cíbola or the Northwest Passage or some other sunny myth, and the Captain John Smith who took skins home to his queen got them along trade routes already old. Then half a dozen countries planted colonies in the New World, and from all these plantations, men went up the rivers—whether a few miles up the James or by the St. Lawrence to the Lakes and then by portage to the Wisconsin and so down the Mississippi—to trade with Indians for the only wealth the Indians had. It was these men who made the unknown known.

Plantations grew to empires, and on the farthermost frontier of New France some of the coureurs de bois fell into contention. Some lost out and two of the disgruntled came in due time to the court of Charles II of England, then withdrawn to Oxford because there was plague in London. The court was bored in that provincial community, no one more bored than the king’s mistresses, whose great silken sleeves could be attractively lined with the beaver, mink, and otter that Radisson and Groseilliers heaped at their feet. So plague and boredom conferred a monopoly on the king’s cousin, the governor, and the Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay. From that moment it was inevitable that two empires in the New World would come to grips. New France went down.

Meanwhile, in all the colonies the Indian trader pushed up the streams, over the divides, and down into the new country. He was the man who knew the wilderness, and he held the admiration of the settlements. Let there follow after him the men who built cabins; his was the edge and the extremity. The settlements saw his paddle flash at the bend or sun glint on his rifle at the edge of the forest, and then there was no word of him till his shout sounded from the ridge and he was back, with furs.

He had to live in the wilderness. That is the point. Woodcraft, forest craft, and river craft were his skill. To read the weather, the streams, the woods; to know the ways of animals and birds; to find food and shelter; to find the Indians when they were his customers or to battle them from stump to stump when they were on the warpath and to know which caprice was on them; to take comfort in flood or blizzard; to move safely through the wilderness, to make the wilderness his bed, his table, and his tool—this was his vocation. And habits and beliefs still deep in the patterns of our mind came to us from him. He was in flight from the sound of an ax, and he lived under a doom that he himself created, but westward he went free.

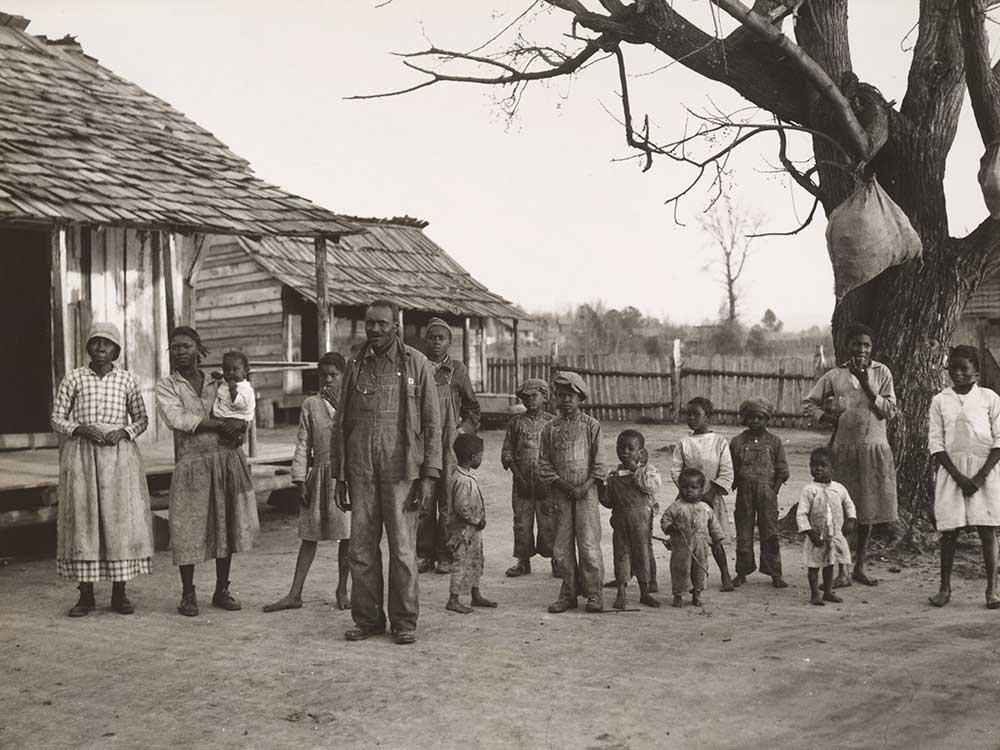

African American family at Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1937. Photograph by Arthur Rothstein. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2001.

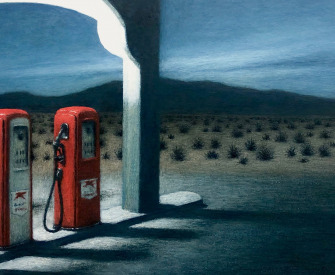

The frontiersman’s craft reached its maximum, and a new loneliness was added to the American soul. The nation had had two symbols of solitude, the forest and the prairies; now it had a third, the mountains. This was the arid country, the land of little rain; the Americans had not known drought. It was the dead country; they had known only fecundity. It was the open country; they had moved through the forests, past the oak openings, to the high prairie grass. It was the country of intense sun; they had always had shade to hide in. The wilderness they had crossed had been a passive wilderness, its ferocity without passion and only loosed when one blundered; but this was an aggressive wilderness, its ferocity came out to meet you, and the conditions of survival required a whole new technique. The long hunter had slipped through forest shadows or paddled his dugout up easy streams, but the mountain man must take to horse in a treeless country whose rivers were far apart and altogether unnavigable. Before this there had been no thirst; now the creek that dwindled in the alkali or the little spring bubbling for a yard or two where the sagebrush turned a brighter green was what your life hung on. Before this one had had only to look for game; now one might go for days without sight of food, learn to live on rattlesnake or prairie dog, or when those failed on the bulbs of desert plants, or when they failed on the stewed gelatin of parfleche soles.

The waters of manitou held freedom and desire, both inappeasable in the American consciousness. Why else the everlasting myth of the West? From Eric the Red to Jim Clyman, from the Atlantic fall line to the Pacific littoral, from The Adventures of Emmera to this week’s horse opera issuing from Hollywood. The seed of expansion, to answer the tug, to push over the ridge, to go it alone. To the destructive element submit yourself, and with the exertions of your hands and feet in the water make the deep, deep sea keep you up. To be a man and to know that you were a man.

And to be a free man. At any evening fire below the Tetons, if they had paid civilization its last fee of contempt, they had recompense in full, and Henry Thoreau had described it. They made their society, and its constraints were just the conditions of nature and their wills, the self-reliance in self-knowledge that Mr. Emerson commended. At that campfire under the Tetons, in the illimitable silence of the mountain night with the great clouds going by overhead, one particular American desire and tradition existed in its final purity. A company of free companions had mastered circumstance in freedom, and their yarns were an odyssey of the man in buckskins who would not be commanded—what scalps had been taken along the Yellowstone, who counted coup in Middle Park, what marvels had been seen in John Colter’s Hell or where the stone trees lie beyond the Painted Desert or where the waters of Beer Spring make the prettiest young squaw quite unattractive for a surprising time. The stories came from a third of a continent and summed up something more than two centuries of the American individual.

Finally, there was the beauty of this last wilderness, added upon all the unspoiled natural beauties through which the individual had passed in his two centuries. The land of little rain, the Shining Mountains. It was theirs before the movers came to blemish it—rivers flowing white water, peaks against the sky, distances of blue mist against the rose-pink buttes, the canyons, the forests, the greasewood flats where the springs sank out of sight. They were the first to pass this way and, heedless of the eagle’s wing that they stretched across the setting sun, they stayed here. God had set the desert in their hearts.

Bernard De Voto

From The Year of Decision: 1846. Born in Utah to an Italian Catholic father and a Mormon mother, De Voto fought in World War I, taught English at Northwestern and Harvard Universities, edited The Saturday Review of Literature, and began his two-decade tenure as Harper’s Easy Chair columnist before devoting himself, in 1938, to writing this first installment in his trilogy of historical studies of the power of the West in the American mind. “De Voto was a Westerner, something Easterners have seldom understood,” wrote his friend and biographer Wallace Stegner, “and a belligerent Westerner at that.”