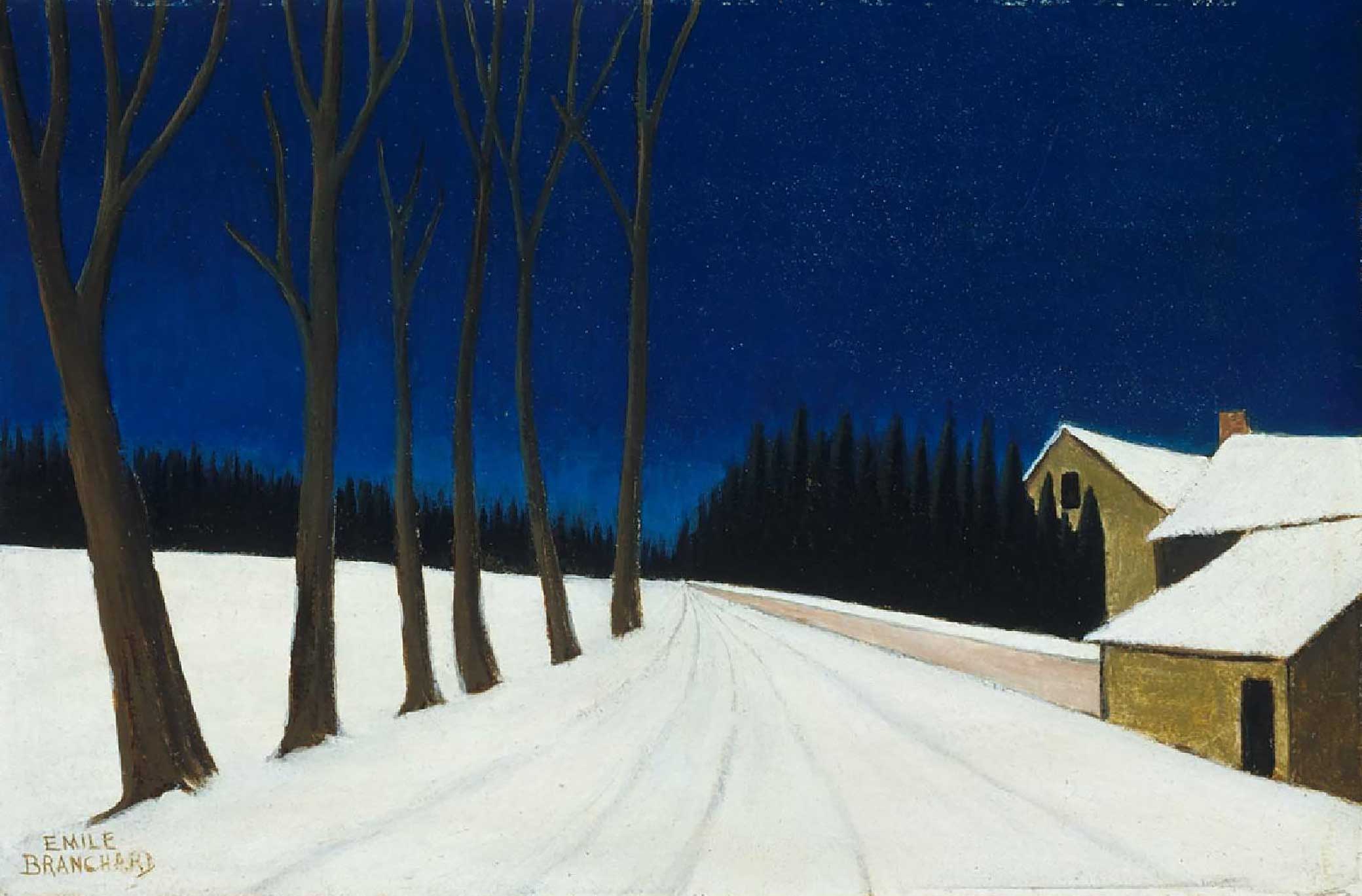

Winter Night, by Emile Branchard, c. 1930. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of John T. Spaulding.

In 2022 our readers loved essays on heavy metal, hunger, and Aldous Huxley. Here are the eight web pieces that attracted the most attention this year.

Kim Beil, “New Look, Same Great Look”

Professional photographers remained skeptical of color film. In instructional guides, they qualified the manufacturers’ claims about natural color. A photographer for the American Museum of Natural History explained in 1941 that Kodachrome “has no subjective reactions. What it sees is not colored by previous knowledge or experience. When the color film sees grass, it doesn’t insist, as we are so apt to, that all grass is green. It may see brown grass or blue grass or other colors that look all wrong to us in the processed film.” Notable photographers, including Berenice Abbott and Louis Stettner, also took care to point out that humans and film “see” color differently. Abbott suggested that some of the difference lay in our past experiences: “When we judge the color photograph, we not only think of how the subject looked in nature, but we also remember how painters throughout the centuries have rendered similar objects. The color photograph has to satisfy a double standard—fidelity to real life and a recognizable approximation to traditional art.” These caveats beg the question: Which color is natural? What we’ve trained ourselves to see or what is out there in the world?

Jeremy Swist, “Enjoy My Flames”

Roman emperors have enjoyed a prolific reception in metal music around the world—Caligula and Nero most of all, with not only hundreds of individual songs but also entire concept albums dedicated to them, such as the Belgian band Paragon Impure’s 2005 album To Gaius! (For the Delivery of Agrippina) and the Russian band Neron Kaisar’s 2013 album Madness of the Tyrant. The year 2021 saw the release of two separate records about Nero: the UK band Acid Age’s Semper Pessimus and the Canadian band Ex Deo’s The Thirteen Years of Nero…The numbers speak for themselves: emperors are metal. But why?

Emma Garman, “Scene Stealer”

The twentysomethings whiled away the night talking and “singing folk songs and ragtime to the stars,” Huxley wrote to a friend. “Early in the morning we would be wakened by a gorgeous great peacock howling like a damned soul or woman wailing for her demon lover, while he stalked about the tiles showing off his plumage to the sunrise.” If you think this scenario belongs in a story, so did Huxley, who put it in his 1921 debut novel, Crome Yellow. Mary and Ivor, who are engaged in a flirtation, climb onto the roof to sleep “under the stars, under the gibbous moon.” At daybreak a “monstrous” peacock appears, emitting “the mournful scream of a soul in pain.”Huxley drew much of that novel directly from the vie bohème at Garsington. At this seventeenth-century hillside manor, set in magnificent Italianate gardens, Lady Ottoline Morrell cultivated an artistic, intellectual, and sexual haven. Except a haven, of course, is marred by the curious gaze of an audience—a consequence to which Huxley paid no heed. Ottoline, shocked by his abdication of the novelist’s duty to make stuff up, denounced Crome Yellow as “simply photography, and poor ragged photography at that.”

Kevin Blankinship, “The House of His Desires”

On a spring night in tenth-century Baghdad, a mob gathered to watch as a sixty-four-year-old man, plainly dressed and rail-thin from nine years spent in the city’s dungeons, was bound to a scaffold and raised over their heads. “My God,” the condemned man cried, “I am now in the house of my desires!” In the crowd were gleeful enemies, sympathizers, and fanatics who wanted to witness a miracle. “What is Sufism?” asked one believer, eager to hear the man’s take on Islam’s mystical path. “The start of it you are seeing here,” he supposedly replied, “and its end you will see tomorrow.”

Jack Hanson, “Finding the Right Angle”

To begin, if not at the beginning, early on: the painter and poet David Jones resumes his studies at the Westminster School of Art in his mid-twenties, not long after his service with the Royal Welch Fusiliers in World War I ended. The 117 weeks he spent in a war that shattered so many millions shattered Jones no less, though the full extent of his brokenness would not appear until over a decade later, in 1932, when the first of two major nervous breakdowns would interrupt work on his first great long poem, In Parenthesis, and keep him from painting for years. As Jones would later suggest, every aspect of his life seemed to revolve around the dilemma that the war had either caused or, as he would come to believe, merely revealed: that modern life was fundamentally fractured. It was up to the artist not so much to heal those fractures as to discover a way of navigating them and in so doing find a way of being at home among them.

Daniel M. Lavery, “Feminine Ending/Masculine Ending”

It is this strange blend of candor and evasion that characterizes two of the most jarring sections in The Gastronomical Me. Both moments take place in the book’s final chapter, “Feminine Ending,” written in 1941 by a thirtysomething M.F.K. Fisher. The episodes involve moments where Fisher outs someone living and working as a man under varying degrees of plausible deniability. She outs one fairly readily and one more reluctantly, and both involve an uneasy return to form afterward as an “open secret.” Both the chapter and A Gastronomical Me end in a literal ellipsis, a gesture profoundly aware of its own insufficiency, as Fisher declines to approach the most immediately relevant events—the sudden deaths by suicide of her husband and her brother in close succession—instead writing about another taboo subject, the transition of two men she scarcely knows. A book about eating, nourishment, and pleasure has no choice but to close on a note of hunger, uncertainty, and uneasy guilt. It’s an unsettling and unusual choice for the genre.

Daniel M. Lavery, “Good Servants and Bad Masters”

Not much can be safely attributed to François Vatel beyond the outline of his biography. Most of the known details about his life come from the three days before his death. Epistoler Madame de Sévigné happened to be staying near Chantilly that weekend and wrote down all she heard of the affair in letters to her daughter, then living in Provence. Vatel had previously served as maître d’hôtel to Nicolas Fouquet, who was France’s superintendent of finances until 1661, when he was disgraced and imprisoned for embezzlement. In 1669, after a brief intermission out of the country, Vatel moved on to his final position with the prince of Condé, who had himself been in disgrace for nearly a decade over his rebellious role in the Fronde before his reinstatement after the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659. Disgrace came fairly cheap in those days. Good maîtres d’hôtel did not.

Carla Cevasco, “Appetite for Destruction”

In 1676 an English minister’s wife named Mary Rowlandson was taken captive from her home in Lancaster, Massachusetts, in a raid by the Nashaway war leader Monoco. As a prisoner, Rowlandson would travel across what is now Massachusetts in a party of Wampanoag, Nipmuc, and Narragansett people led by Weetamoo, the Pocasset Wampanoag saunkskwa, or female leader. On the day of the raid, one member of the party gave Rowlandson a piece of cake. Rowlandson put the cake in her pocket, where it remained for weeks, molding, crumbling, and finally desiccating into shards. Over her eleven-week journey, Rowlandson would reach into her pocket for those dry crumbs. Whenever she ate one, she thought that if she ever returned from captivity, she “would tell the world what a blessing the Lord gave to such mean food.” From a modern, secular viewpoint, Rowlandson’s story is a strange one, strangely told. Yet in the late seventeenth century, it was consumed with voracious appetite by English-reading audiences on both sides of the Atlantic.

Lapham’s Quarterly also highlighted many recently published works of history. Here are the book excerpts that found the most readers.

Brian Michael Murphy, “Panic at the Library,” from We the Dead: Preserving Data at the End of the World (University of North Carolina Press)

Reading and touching library books brought one into contact with the bodies, germs, and contagions of others. Books, like smallpox blankets, could be infected, and like people with contagious diseases, infected books were fumigated, treated, quarantined, and in some cases destroyed. One researcher experimentally infected books with scarlet fever and found that the dreadful germs could survive for eighteen days even in “lightly infected books.” Public health officials compelled librarians, by law, to literally sterilize books during epidemics by closing libraries and fumigating the stacks with poison gas. The cover of the February 1915 monthly bulletin of the Los Angeles Public Library, Library Books, informed readers of borrowing policies on its front page, concluding with a sentence clearly intended to comfort visitors and allay fears: “The library receives notice of all cases of contagious disease. No book may be drawn or returned by anyone living in a house where there is a contagious disease until the house and the book have been fumigated.”

Matthew Green, “These Destroyers of Towns,” from Shadowlands: A Journey Through Britain’s Lost Cities and Vanished Villages (W.W. Norton)

It is impossible to say exactly how the inhabitants of Wharram Percy in North Yorkshire, often described as “Europe’s best-known deserted medieval village,” experienced the plague. Established in the late Anglo-Saxon period, between 850 and 950, Wharram Percy exists on the site of an earlier Middle Saxon settlement, and was continuously occupied for around six hundred years. It was part of a broader trend—the rise of the village. No one could have known that the village lay in the “shadow of annihilation.”

Elise Vernon Pearlstine, “A Brief History of Frankincense,” from Scent: A Natural History of Fragrance (Yale University Press)

Small and gnarled, often showing its age, the frankincense tree grows in an Arabian Desert wadi where water occasionally flows in the winter. Its bark is papery and peeling in places, on it a tiny beetle is trapped in resin, and the trunk glistens where it is coated with the sticky stuff. Farther below there are small drops like liquid tears that turned solid as they traced a path down the trunk. If you were to put a hand on the tree, you might come away with a bit of scented resin softened by the hot sun into a sticky patch: the scent is resinous but also lemony and soft and subtly appealing.

John Higgs, “God Has a Beautiful Mansion for Me Elsewhere,” from William Blake vs. the World (Pegasus Books)

What made Blake so fascinating was the casual way in which he talked about his relationship with the spirit world. Blake, Robinson wrote, “spoke of his paintings as being what he had seen in his visions—and when he said ‘my visions’ it was in the ordinary unemphatic tone in which we speak of trivial matters that everyone understands and cares nothing about.” Blake peppered his conversation with remarks about his relationship with various angels, the nature of the devil, and his visionary meetings with historical figures such as Socrates, Milton, and Jesus Christ. Somehow, he did this in a way that people found endearing rather than disturbing. As Robinson wrote, “There is a natural sweetness and gentility about Blake which are delightful. And when he is not referring to his visions he talks sensibly and acutely.”

Geoffrey Roberts, “A Dictator’s Marginalia,” from Stalin’s Library: A Dictator and His Books (Yale University Press)

Charles Dickens may well have been among the writers read by Stalin. Dickens was studied in Soviet schools and his writings used to teach English. The Bolsheviks didn’t like all his novels (the antirevolutionary A Tale of Two Cities, for example), but they relished his bleak descriptions of nineteenth-century industrial capitalism. Appealing to puritanical Bolsheviks like Stalin would have been the complete absence in Dickens of any mention of physical sexuality. As far as we know, Stalin never wrote Scrooge’s famous expletive “bah humbug” in the margin of any of his books, but he used plenty of Russian equivalents. Among his choice expressions of disdain were “ha ha,” “gibberish,” “nonsense,” “rubbish,” “fool,” “scumbag,” “scoundrel,” and “piss off.”

Penelope J. Corfield, “What Driveling Times Are These!” from The Georgians: The Deeds and Misdeeds of 18th-Century Britain (Yale University Press)

Grumbling is, after all, a human reflex, especially among the ill and embittered. In 1769 one commentator announced (without proof) that “we are almost universally unhappy.” Farmers who were subject to the vagaries of the weather were particularly famous complainers. The touring missionary John Wesley noted that characteristic in 1766. Observing the country farmers, he remarked, “In general, their life is supremely dull, and it is usually unhappy too.” Yet townspeople were also vociferous in complaining. “Gloom and misanthropy have become the characteristics of the age in which we live,” mourned Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1817, temporarily downcast by the weakness of reform campaigns. Getting into the market for pessimism, a poet in 1840 versified eloquently about the current Age of Lead, declaiming: “What doleful days! What driveling times are these!”

Maria Golia, “Policing the Necropolis,” from A Short History of Tomb-Raiding: The Epic Hunt for Egypt’s Treasures (Reaktion Books)

Anyone who has spent time in the desert has known a silence so profound that one can almost hear the sun’s rays hitting the ground. Sound was the tomb raider’s enemy; airborne it might easily reach the Medjay, the necropolis police, in their outposts along the mountains, or the priests performing rituals at royal tombs. The tomb doors were visible but sealed so that any disturbance would be obvious. Tunneling into them was tough going; a group of eight men might take a week to clear pits and shafts to penetrate a burial chamber. The utmost stealth was required so the raiders worked after dark. It helped that the necropolis had grown crowded; sometimes they could tunnel from one tomb straight into another. Once they’d gathered the loot, they took it to a secluded place and lit a fire, burning the wooden coffins or statues coated in gold or silver and recovering the pools of molten metal from the cinders once they had hardened in the night-cooled sand.

Gregory Claeys, “Making an Enemy of Luxury,” from Utopianism for a Dying Planet: Life After Consumerism (Princeton University Press)

The literary utopia came frequently to symbolize resistance to, or at least contempt for, increasing inequality and luxury. It doubtless echoed nostalgia for a world being rapidly lost, a sense of guilt at the abundant selfishness of the age, as well as the appeal of new primitive worlds now being discovered and conquered. To focus on Britain briefly, four models of virtuous restraint dominate eighteenth- and nineteenth-century debates: the idea of an arcadian state of nature, often without private property, where luxury does not yet exist; the primitive Christian community, often with uniform dress and consumption and prohibitions on frivolity and luxury; the classical republican ideal, where property and often trade are limited; and a Tory or Country Party ideal, where corruption is associated with the growing predominance of a Whiggish commercial interest, and contrasted with a virtuous landed interest and patriot-king. Utopian texts thus echoed the wider debate of the period between opponents of commercial development, notably Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and its defenders, like David Hume and Adam Smith.