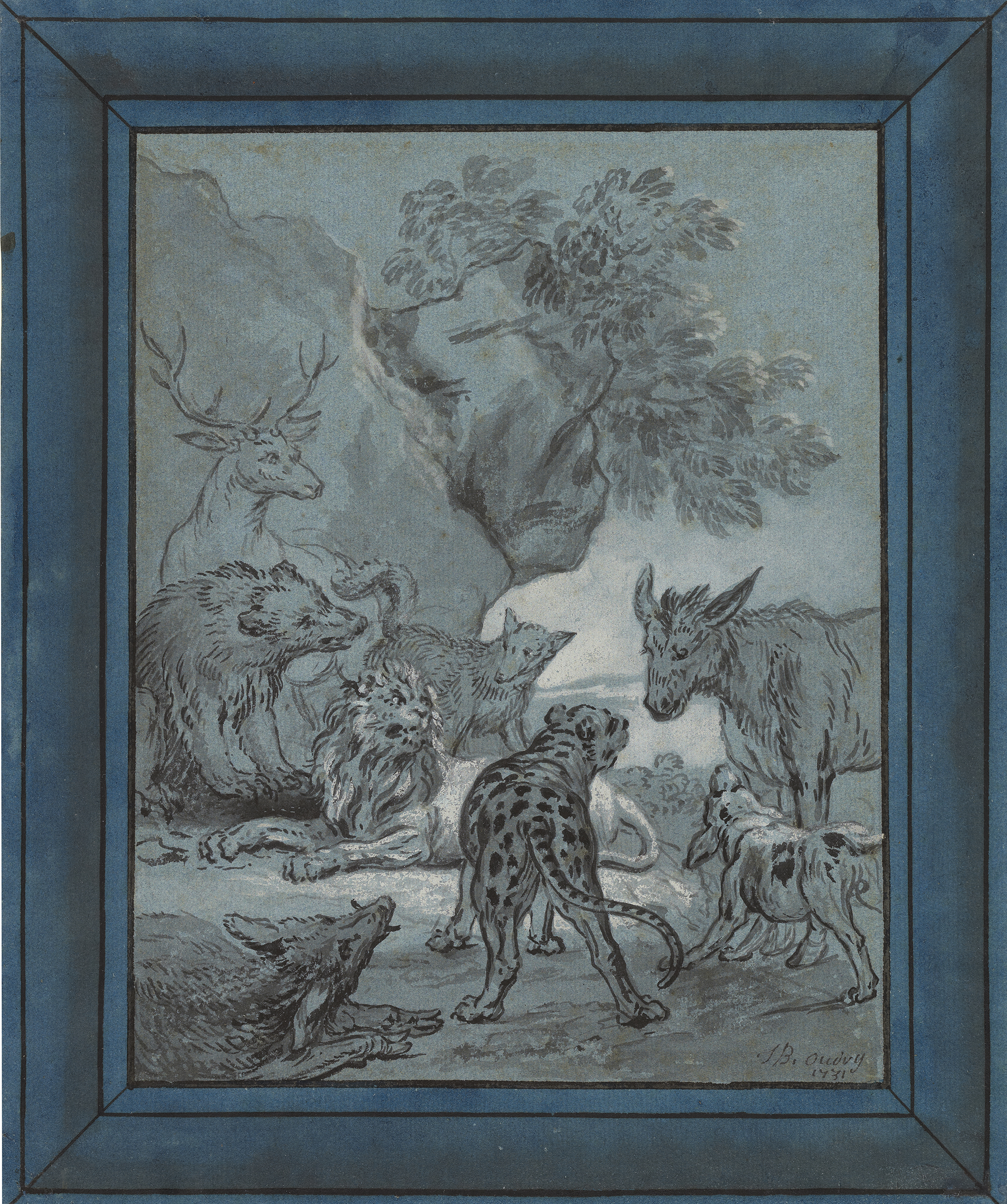

The Plague-Stricken Animals, by Jean-Baptiste Oudry, 1731. © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

A plague falls on the animals. All are attacked and many die. Those who escape death suffer despair. Foxes and wolves lose interest in their prey. Turtledoves no longer coo in pairs, avoiding company instead. Sex ceases.

Appearing in book seven of Jean de La Fontaine’s 1678 collection, “Animals Sick with the Plague” is full of animal archetypes easily recognizable 432 years later: the regal lion, the sly fox, the humble donkey. Evoking Oedipus Rex, the fable begins by describing a terrible plague sent on the animal kingdom from heaven with the intention of punishing “the crimes of the earth.” Animals may have been lifeless machines in the eyes of Descartes, but they proved a convenient device for satisfying the Enlightenment fetish of universality. Someone in another country, or another era, might not know what a more individually developed character reflecting local culture was intended to exemplify; a fable’s moral would be unintelligible without widely readable narrative examples. Animals serve well as stock characters, making a story from the seventeenth century useful for examining a plague and our response to it centuries later.

In the sick-animals fable, plague leaves almost no feature of life unchanged. No one eats; no one falls in love or experiences joy; many die. Only two things remain constant: the reach of power and the sanctity of ownership. If La Fontaine did in fact seek the kind of universality to which Enlightenment theorists of literary form thought the fable aspired, he may have achieved it.

Casually considered the French Aesop, La Fontaine—one of the most popular poets of the seventeenth century and a member of the Académie Française—has been a mainstay of French schoolroom literature for centuries. Some critics divide La Fontaine’s fables into two categories. Fables of the first kind hew closely to Aesop, have conventional forms and narrative structures, and issue clear, unambiguous morals: patience is preferable to haste; the one who tries to catch will get caught; beware of flatterers. Fables of the second kind—perhaps more characteristic of La Fontaine—depart from tradition in structure and form. Their morals can be inferred only with difficulty; his fable “The Wolf and the Lamb” builds sympathy for a victim whose actual death is described in completely unsympathetic terms (“the wolf takes him away and eats him”). Supposing we accept this division into two categories, the sick-animals fable would almost certainly be classified in the first.

The oldest attested animal fable (αἶνος) in Greek literature appears in Hesiod’s eighth-century bc Works and Days. Ostensibly concerning a nightingale seized by a hungry hawk unmoved by the nightingale’s pleas for mercy, its true subjects are power and disaster—particularly the kind of disaster visited on the subjects of reckless, evil-minded kings who make “crooked judgments.” Hesiod addresses his fable directly to kings who, he says, “themselves understand,” their conduct notwithstanding. From Achilles’ divine horse warning him against avenging Patroclus’ death in the Iliad follow many examples of animals being used to correct wayward leaders in classical literature, but the fables best known to speakers of modern European languages derive mostly from Aesop. Though the existence of a single, historical person “Aesop” remains disputed, a fifth-century bc collection attributed to him includes many animal fables later recast (often with only minor variations) by La Fontaine. Vernacular variations on Aesop became well-known largely because leading early modern humanists recommended their use in education. This was true of the philosopher John Locke in England and of the then influential poet, polemicist, and theologian François Fénelon in France.

There is widespread agreement that the purpose of the fable, ancient and modern alike, is didactic. There is less agreement about what kinds of lessons the fable was supposed to teach, how it was supposed to teach them, and to whom. The standard view is that, at least in France, fables like La Fontaine’s were meant to inculcate bienséance, good conduct, the propriety of an elite. But their morals are often quite radical. More often than not, La Fontaine is a critic of power. He shows how it can be wielded unjustly in times of crisis, cautioning readers against the self-interest of leaders and those close to them.

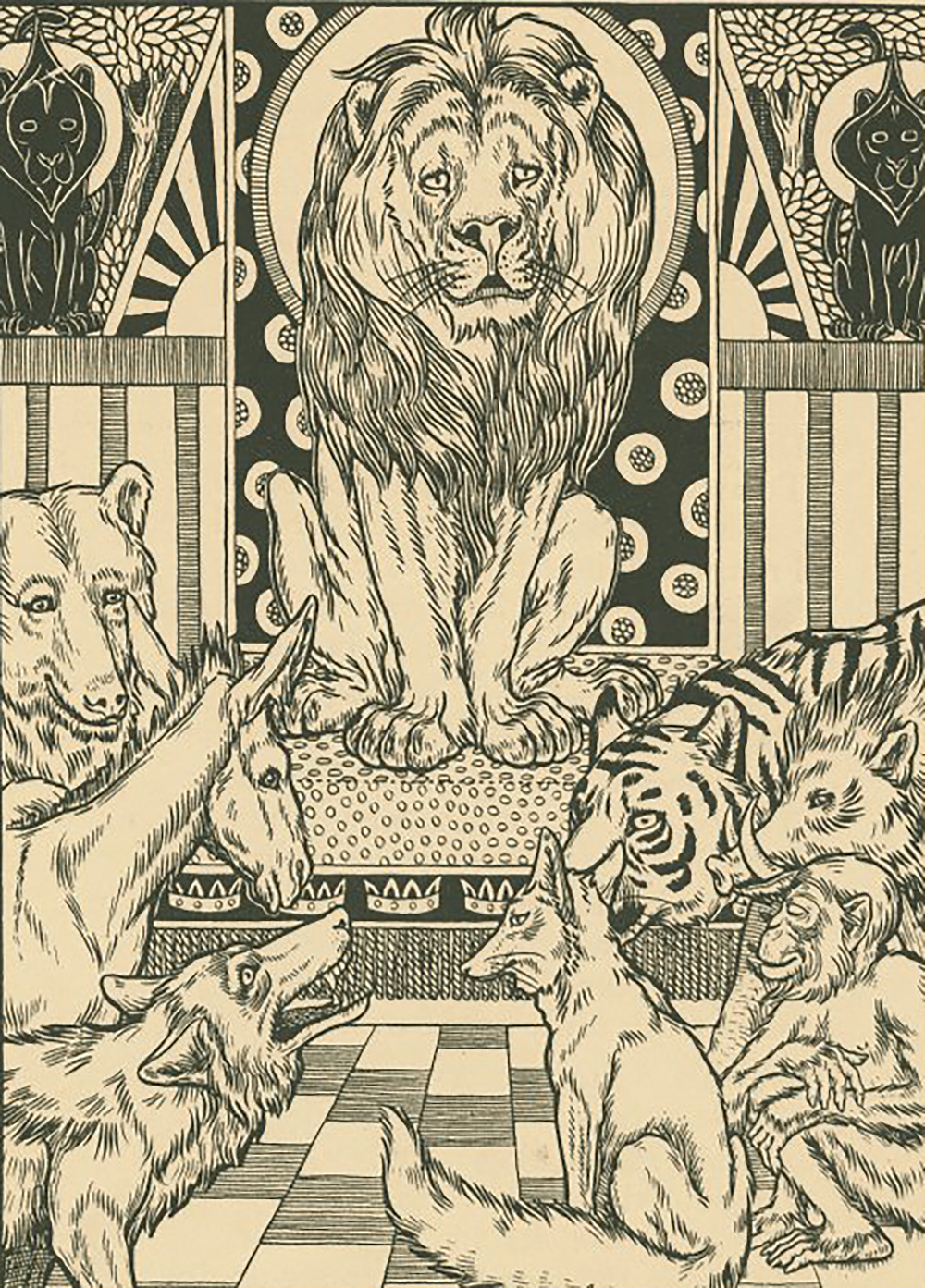

In La Fontaine’s fable, after the plague strikes, the lion calls a council. Speaking first, the lion is careful to preserve the appearance of equality despite his obvious authority. “My dear friends,” he begins. The lion observes what the fable’s narrator has already told its readers: that heaven has sent a plague to punish the crimes of the animals, and that a sacrifice is required to appease the “celestial wrath” and achieve “communal recovery.” Again, the collective of the animals is emphasized, though only the sovereign speaks. The example of history is cited: this is what is done in cases like these.

Whose crimes occasioned so indiscriminate a calamity as this terrible plague? Like a Jesuit confessor, the lion proposes a collective examination of conscience—a comparative study of misconduct on the fly, with standards that will prove to be less objective than exculpatory. He leads by example, admitting his own gluttonous sheep-eating. He knows the sheep did nothing to deserve being eaten: they committed “no offense.” Sometimes, the lion admits further, he has even gone so far as to eat their shepherd. The lion offers to make of himself a willing sacrifice, if this should prove necessary. But in order that justice be done, he insists on a general confession so that only the most guilty might perish.

The fox goes next. Addressing the lion as “sire,” the fox praises the lion as a generous king, making explicit the latter’s sovereignty. The fox dismisses each of the lion’s admitted misdeeds. It is no crime to eat sheep, the fox argues, because they are foolish and ill-behaved. On the contrary, the lion’s jaws did them honor. As for the shepherd, the fox insists he deserved what came to him; he was, after all, one of those who pretend to rule over the animals. The fox plays the part of the staunch royalist. The king can have no guilt: his weaker animal victims should be honored by his criminal attentions. The lion’s human victim earned his fate by his false pretense of sovereignty. In each argument, the lion’s political sovereignty absolves his guilt.

At the conclusion of the fox’s speech, the council of animals applauds. The other animals are of the same mind. But the fable’s narrator begins to cue a different judgment, calling the fox and his allies in council “flatterers.” The other meat-eating animals—from tiger to bear to watchdog—follow the fox’s example, lining up to lessen their own crimes (“the least pardonable,” the narrator reminds us) and praise their king. The fable’s narrator tartly observes the irony of such aggressors preening like “little saints.”

Then the donkey confesses: he has eaten a mouthful of grass. He was hungry—a pasture’s tender grass beckoned. He knew it was wrong; the field belonged to a monastery. His apology is sincere. He knows he had “no right,” he says. No one has been eaten or killed, but property has been violated.

All at once the far guiltier animals—much higher on the food chain—turn on the donkey. With great ferocity the wolf harangues him, denouncing him as hairless, mangy, and the source of all evil. To eat someone else’s grass—what an abominable crime! The wolf urges without hesitation: nothing but death is possible for the wicked donkey.

The narrative action of the fable comes to an end with the donkey’s implied demise, but the narration delivers a further conclusion. “As you are mighty or meek,” the fable warns, “the court’s judgments will find you innocent or guilty.” What we have been shown, La Fontaine leaves little doubt, is the conviction of the innocent (the weak) by the guilty (the powerful). The innocent’s “unforgivable” crime? To eat, out of hunger, what is not his: to violate the law of property, the mainstay of power.

Plagues were commonly regarded in the literature of the early modern period as punishments for sin, though the sin being punished was not always so readily discerned. Nevertheless, it would be difficult to read La Fontaine’s fable of the sick animals and see him as anything but a skeptic of sovereignty. La Fontaine’s intended readers had often not yet assumed power. La Fontaine’s 1668 collection was dedicated to Louis de France, the seven-year-old dauphin; in 1692 the collection’s last book was written for the dauphin’s son, the then ten-year-old Duc de Bourgogne. Following Hesiod, La Fontaine critiques wicked kings under the guise of educating good ones. On the other hand, he remained popular after the Revolution. Indeed, in the sick-animals fable, the mechanism of legitimate authority is depicted as vapid, a self-serving exercise in flattery. The operation of justice is shown as wholly independent of innocence or guilt, being tied instead to power and the privilege of judgment. Murder, even serial murder, is not a condemnable offense. Every crime in the sick-animals fable has its apologist except one: the crime of theft. Power protects property. The weak will be condemned and the guilty judged innocent.

If there’s any unresolved question about La Fontaine’s sick-animals fable, it’s how this radical critique of power and property achieved canonical status in a genre dedicated to the cultivation of propriety—bienséance. Hiding in plain sight, La Fontaine offers a simple story of hypocrisy and inequality that has more to teach those excluded from power than those who exercise it. The fable is brief and darkly philosophical. It has no real ending. In the world of the fable, would heaven really be placated by the unjust sacrifice of the almost innocent donkey? If not, wouldn’t the plague continue? Won’t the lion, at length, fall? Who might then replace him—a more equitable collectivity? It is tempting to think that still wider disaster can correct the errors of a more temporary social order—though at what price, one may wonder. Everything is earth in the long run; power can defer sickness, but no one can escape it altogether. Ecology takes over; a more immutable order of law, harsh and blind, is installed.

In the best-known modern example of plague literature in French, Camus’ The Plague, contagion again provides a pretext for the oppressive exercise of power. Animals, however, play a very different role. A rat is merely a carrier of disease, a limited and unknowable other; people are depicted with interiority, intention, agency. Camus’ evocation of fascism, for all its humanistic interest, obscures the stark reality of politics under emergency. La Fontaine’s stock animals make this clear: the strong will sacrifice the weak. What happens next, when plague continues, is less clear.