Chafariz d’el Rey in the Alfama District (View of a Square with the King’s Fountain in Lisbon), by anonymous, c. 1570–80. Wikimedia Commons, Berardo Collection Museum.

On Sunday, September 17, 1882, at 8:30 pm, the doors opened on a lavish gala at a grand house in Travessa do Outeiro, a street not far from Lisbon’s Estrela Garden and the Basilica da Estrela, the city’s magnificent late baroque church. Newspaper advertisements, posters and flyers had announced the event. They promised that it would be “dazzling.” The entertainment included rides in a tethered balloon, and there were salutes fired by mortars followed by “a splendid ball.” The occasion merited extravagance. It was the coronation ceremony of the new queen of Kongo, Amália I. It would, the advertisements declared, be a “great party of the Congolese court to mark in a solemn manner such a majestic and august day.”

The coronation in nineteenth-century Lisbon of a West African queen is not as puzzling as it might appear. From the fifteenth century onward the Portuguese went to Africa, and Africa came to Portugal. Most Africans came as slaves, and in large numbers. By the mid-sixteenth century, there were almost ten thousand black slaves in Lisbon, representing around 10 percent of the city’s population. It was a remarkable number that distinguished the city from the rest of the continent. People of African heritage are a common sight today in postcolonial Western Europe, but in the sixteenth century, they weren’t. Vivid traits of Africa have been a Lisbon hallmark for centuries, and remain so. “The city’s history cannot be told,” says Angolan novelist José Eduardo Agualusa, “without talking about those thousands of Africans who over the centuries have settled in the Portuguese capital, enriching it and reinventing it.”

On their voyages during the Age of Expansion the Portuguese made friends where they could. Apart from the slaves they brought home, some Africans stepped onto the Lisbon quayside as free men and women. The Portuguese especially sought to educate in Lisbon indigenous people who might return to Africa as clergy. German physician Hieronymus Münzer, visiting Lisbon in 1494, reported young black men being taught Latin and theology. The goal was to send them back to Africa as missionaries, interpreters, and envoys of the Portuguese Crown.

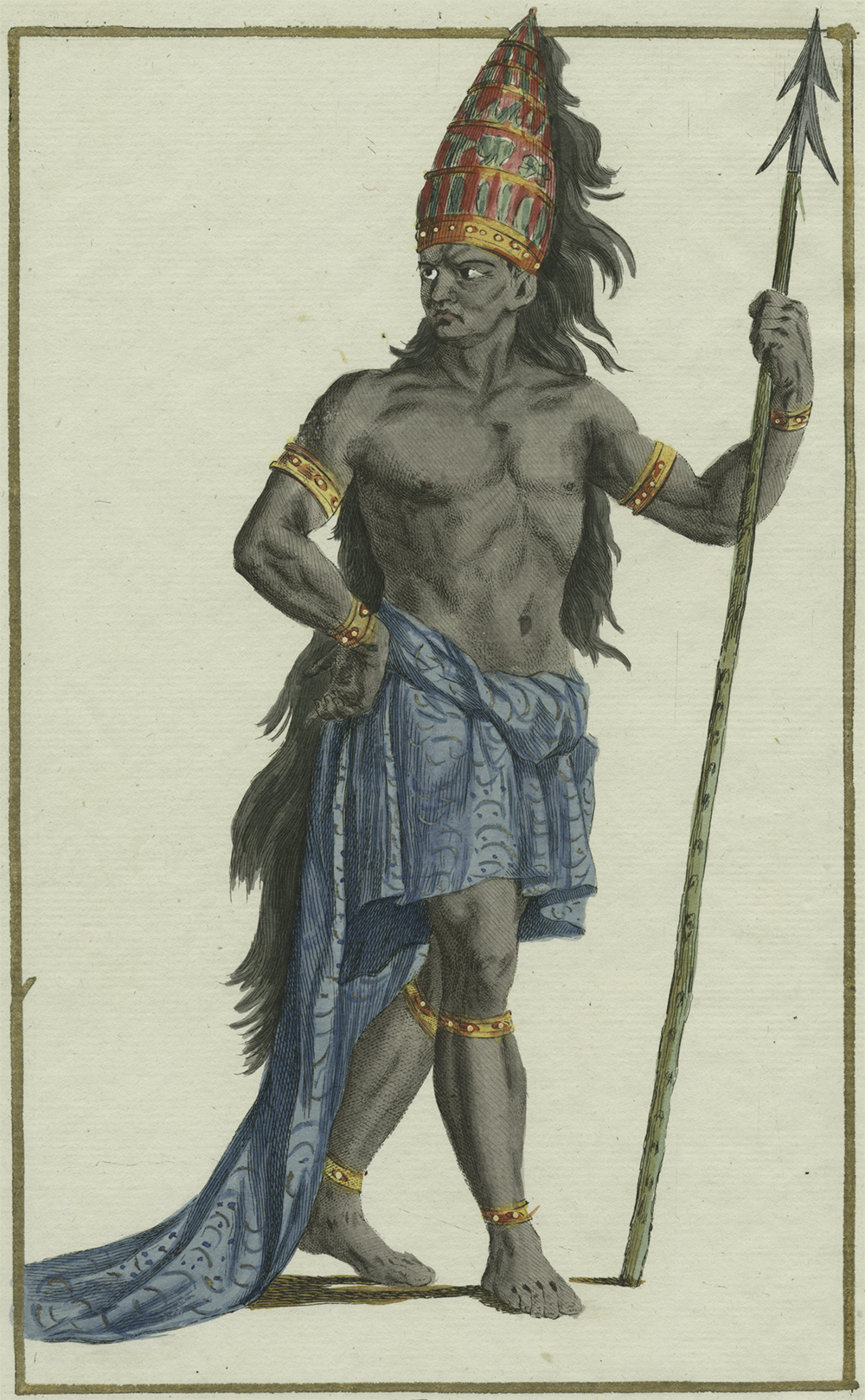

The distinguished visitors to Lisbon from distant outposts of empire included royalty from the then Kingdom of Kongo, in west-central Africa, now partly Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Portuguese explorers reached Kongo in 1483 and forged alliances. Eight years later, Kongo’s tribal leader Nzinga a Nkuwu was baptized and took the title João I of Kongo. His son, and eventual successor, Mvemba a Nzinga also took the sacrament and later became Afonso I of Kongo. Their ambassadors and family relations traveled freely to the Portuguese capital.

Several centuries later, princesses from these lands still had a residence in Lisbon, in a quarter called Mocambo that had a strong African presence. They held balls at which dishes from both Europe and Africa were served, according to Isabel Castro Henriques, a Lisbon University historian.

Queen Amália I’s coronation party was advertised in the weekly Lisbon newspaper O António Maria. As well as entertainment, the ceremonies included “the granting of honorary distinctions, commendations, titles, etc.” That detail was not as innocent as it seemed. The queen’s trip to Portugal and her sojourn in Lisbon were a drain on the royal Kongolese purse. Her retinue was composed of a private secretary, six high dignitaries with their consorts, and a cook. As a consequence, not only were the titles and commendations for sale, but an entrance fee was charged at the door. The newspaper advertisement was appropriately egalitarian.

“All Portuguese and others are invited to join the party, thus deepening the ties of friendship and fraternity with the subjects of the new queen,” it said. Above this phrase was a sketched silhouette of a plump African woman wearing a crown and with two attendants. At the bottom was a similar sketch in negative, showing a portly male figure—bearing a resemblance to King Luís I of Portugal—and two attendants, white on a black background. Beneath it was the phrase “Black or white, all courts look alike.”

Queen Amália’s story has a twist in the tale. She eventually gave up the throne and ran away with a wealthy Portuguese farmer to the country’s southern Alentejo region, near Évora. She reportedly bore many children and lived to the age of eighty-two. Lisbon City Council named a street after her, Rua Rainha do Congo, in 1989. The plaque describes her as a “celebrated personage.”

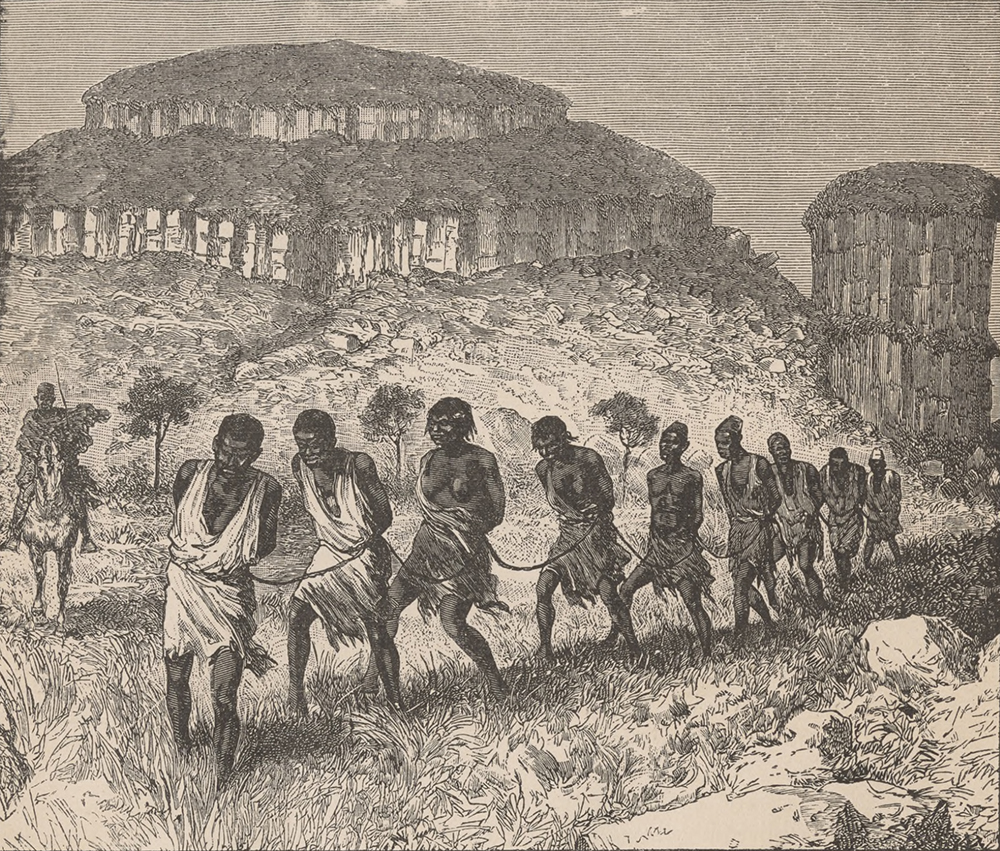

Queen Amália, however, was one of the exceptions in the frequently grim narrative of Africans in Portugal. The Portuguese were the world’s biggest slavers. They trafficked around 5.8 million across the Atlantic, mostly from Africa and mostly to plantations and gold mines in Brazil, between 1501 and 1875, according to data gathered from archives in a dozen countries by Emory University. That was almost double the total of Britain, which had the second-highest count. It is a dark side of the voyages of discovery, and a truth seldom spoken in Portugal. There is no slavery museum in Lisbon like the one in Liverpool or at the Museum of London. A memorial to slaves was planned for the riverside area in 2018, however, after the project won enough votes in the city council’s annual participatory budget, which balloted local people on how they wanted part of Lisbon’s revenue spent.

The first major delivery of African slaves in Portugal—and perhaps Europe—occurred along the southern Portuguese coast, in Lagos Bay, on August 8, 1444. The arrival of the 235 slaves was watched by Prince Henry the Navigator, mounted on a horse. The scene was memorably recounted by chronicler Gomes Eanes de Zurara, who wondered, “What heart, however hard, could fail but to be stung at the sight of such an event?” In Africa, the slaves were commonly exchanged for glass beads or tin or copper baubles.

A papal bull of 1454 required slaves to be baptized. They were then given Christian names. Following King Manuel I’s 1512 decree that slaves could be offloaded only in the port of Lisbon, centralizing the trade in the capital city, they were baptized at the Igreja da Conceição, behind Terreiro do Paço. The church stood on the site of Little Jerusalem’s onetime synagogue. The church is still there, pinched by the heavy downtown traffic, though little more than its elaborate Manueline-style doorway survived the 1755 earthquake. The church’s location made it convenient to serve the profitable sixteenth-century West African slave business. The Casa dos Escravos (Slave House) was a department of the Casa da Guiné (Guinea House), which stood on the nearby riverbank. That was where the slave registrar had his office, as well as two large, lockable rooms for the latest batch of arrivals. Norms written in 1509 established procedures for new arrivals: a detachment of royal officials went out into the river to inspect arriving slave ships. The slaves were brought on deck and counted. They were then taken to the Casa dos Escravos, where they were physically assessed. A price was written on parchment and hung around their necks.

They were sold in public, usually in the square called Largo do Pelourinho Velho, by Rua Nova dos Mercadores, though sometimes they were paraded through the city streets and sold to whoever made a bid. Sales were overseen by a licensed “trader in beasts and slaves.” The sale and the owner’s name were recorded at the Alfândega (Customs House) on the other side of the square, though those duties later moved to the new Casa da Índia (India House). The Crown levied a 25 percent tax, known as a quarto, on sales.

Though records are far from complete, a census in 1551–52 suggested Lisbon had just shy of 10,000 slaves. That was equivalent to roughly 10 percent of the city’s population. In 1620 there were just over 10,000 slaves in a city with a population of some 143,000. In the first half of the eighteenth century, the proportion was 22,500 in 150,000 residents. Anthropologist Didier Lahon reckons that from the second half of the fifteenth century to 1761, when new slave arrivals were banned, around 400,000 slaves were brought to Portugal. Almost all were Africans, though some came from kingdoms around the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea.

“Do you know what the difference was between the king and a prostitute?” asked French writer and anthropologist Jean-Yves Loude, who has explored Lisbon’s African legacy. “None. They both kept slaves. It was said that the only ones who didn’t have slaves at that time [in the sixteenth century] in Lisbon were the beggars.”

Excerpted from Queen of the Sea: A History of Lisbon by Barry Hatton. Copyright © 2018 by Barry Hatton. First published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by Hurst & Co. Distributed in the United States, Canada, and Latin America by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.