Mummy masks

After first wrapping the dead in strips of linen, some ancient Egyptians in the Ptolemaic and early Roman periods covered mummies in cartonnage, a papier-mâché-like substance made of old papyrus—scraps of writing that were no longer needed—or linen and covered in plaster. Cartonnage was also used to make masks painted with idealized likenesses of the deceased. By examining the papyri preserved in cartonnage masks and coverings, scholars now know that Egyptians used papyrus to write shopping lists, land surveys, tax bills, and notes. Cartonnage papyri are one of the most important sources of information about the lives of average Egyptians.

Palimpsests

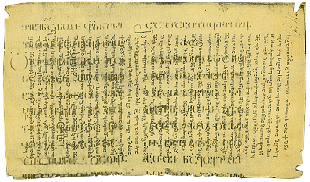

Because parchment was expensive and time-consuming to produce (a Bible on parchment used the skins of approximately two hundred sheep), the pages from unwanted, unused, or even banned books were often washed of their words and reinscribed. These double-inscribed pages, called palimpsests, can sometimes give us access to books that would otherwise have been lost. If the recycler did a good job of cleaning the parchment, deciphering the undertext can be difficult, requiring the help of multispectral imaging technology. A tenth-century manuscript from Egypt housed in the British Library is a rare double palimpsest: both its undertexts are in Latin, a seventh-century grammar and the fifth-century fragments of a second-century history.

Book bindings

Vellum and parchment were common bookbinding material in the early modern period. The vellum—often undecorated and used for everyday or common books—could cover boards or be used on its own. Because vellum was expensive, recycled vellum from unwanted manuscripts, called manuscript waste, was often used in bookbinding. Some important manuscript fragments survive only because they were repurposed as bindings. In 1984 the Folger Shakespeare Library’s head of conservation discovered the oldest extant manuscript from England—a seventh-century ecclesiastical history—in the binding of two sixteenth-century medical texts. When printing began to outstrip manuscript production, damaged, defective, or leftover printed material (printed waste) also found their way into bookbindings.

“Brown” paper goods

Rag paper, made of recycled textiles, overtook parchment as the preferred substance for books in the fifteenth century. Up through the nineteenth century households collected rags to sell or trade to a rag peddler. When rag-paper books were themselves pulped, the resulting pulp, adulterated by the book’s ink, was used for brown paperboard or packing paper, rather than the white rag paper used for printing and writing. In the 1770s a German jurist named Justus Claproth experimented with washing printer’s ink out of recycled rag-paper pulp so that the pulp could be used for new books, but de-inking would not be widely adopted until wood-pulp paper came to dominate book manufacturing.

Toilet paper, insulation, new books

Once books were made from wood pulp, rather than rags or skins, and an industrial process for de-inking was invented, it became possible to turn unwanted books back into pulp; that de-inked pulp could in turn produce more books or other paper goods. When raw materials became scarce during World War I, the U.S. government set up the Waste Reclamation Service, which sent remaindered books to recycling plants to be pulped. As of 2012 13 percent of pulp in books was recycled from old books or other paper goods. Book pulp is routinely recycled into toilet paper, paper towels, tissues, animal bedding, and insulation.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.