At first, joining the Ku Klux Klan meant signing up for a fiddle group. On an evening in May 1866, young men in Pulaski, Tennessee, met in a judge’s office, eager to start “a club of society of some description.”

Pulaski was never a battlefield, but long bloody conflicts like the Battles of Nashville and Shiloh took place nearby, and the town was stressed by Union troops. The fiddle players were college-educated ex-Confederates who knew Greek and understood the mystifying powers of a fraternal club. Secret men’s fraternities like Kuklos Adelphon, founded at the University of North Carolina in 1812, had proliferated in the antebellum period. After spitballing, the fiddlers settled on a club name with gibberish origins—the Greek word kuklos means a band or circle, which morphed into kukloi before someone yelled out “Ku-Klux.” Klan completed the alliteration. (Changing c’s to k’s was a linguistic fad of the mid-nineteenth century.)

Newspapers played a sensationalizing role throughout the first wave of the Klan, as historian Elaine Frantz Parsons argues in her 2015 book Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction—the first comprehensive examination of the Reconstruction Klan since the 1970s. Using newspaper archives, Parsons illustrates that the first wave of the Klan was very much a hodgepodge movement deft at wielding media attention. In the nineteenth century political mobilization was closely tied to public amusements like parades and picnics. Supposedly distinct categories like “entertainment” and “politics” were, as always, not neatly separated, and former Confederates saw social utility in tournaments, balls, and masquerades. All of which could be used to rebuild, or enshrine nostalgia for, antebellum Southern culture, including the racial hierarchy of the plantation. The first wave of the Klan, which advertised itself as a nonviolent minstrel group, or an apolitical drinking club, fits neatly in this trend. It was never a proper-noun political organization but instead functioned as a cultural meme that spread primarily through sensational newspaper reporting and the Klan’s own mythmaking.

Stories published in Pulaski’s local newspaper, the Pulaski Citizen, workshopped the Klan’s image, preparing its symbology for growth and geographical reach as it outcompeted similar groups like the Knights of the White Camelia, originating in Louisiana, or the White Brotherhood and the Invisible Empire, in North Carolina. The Citizen advocated for rogue justice against “horse thieves, housebreakers, loafers, and whisky-heads of this community” to correct “their propensities for committing depredations upon the public and reveling in their midnight orgies.” The paper’s reporters and editors decided that an “organized theatrical club” was necessary to combat vice and reassert the classical Southern values destroyed by war. Such a club would also need proper costumes.

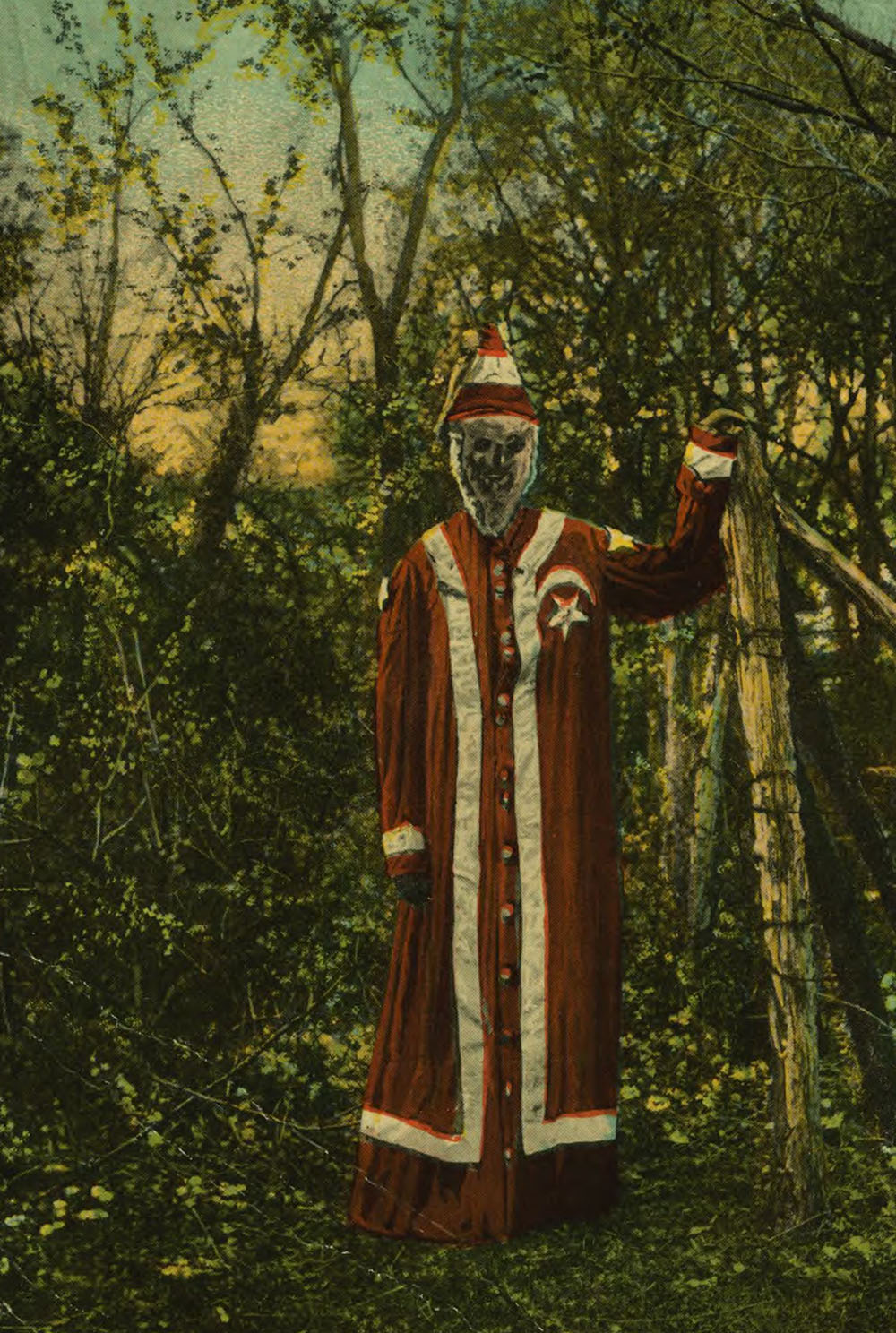

Technological innovations in fabrics, dyeing, and sewing made cheap costuming a popular novelty as public carnival processions became more common during the postwar period. As described by Pulaski Klan members J.C. Lester and D.L. Wilson in a 1905 book, the original Klan preferred a domino mask for the face and a “fantastic cardboard hat, so constructed as to increase the wearer’s apparent height; a gown or robe of sufficient length to cover the entire person.” The cone hat was a co-option of the capuchon—a mocking rip-off of the medieval clergy’s miter hat worn during Mardi Gras. The wearer of the Klan’s towering headpiece struck an imposing figure while projecting a kind of religious authority. The hat made its public debut at the Pulaski Klan’s first parade, in the summer of 1867.

As the Klan evolved into an intensely violent terrorist movement, the occultism and alternately intimidating and mocking costumes created a fog of doubt about the group’s membership and intentions. That mystery lent power to the group, which is often portrayed as a sui generis American phenomenon. But from the start, the Klan had no stable truth or message. It adopted an ad hoc and incoherent ideology, drawing from pop culture sources such as minstrelsy and New York theater. The tall paper hats and robes jeer a long-gone French aristocracy, because the Klan’s combination of music, parade, and dress-up used for intimidation did not originate in North America. The costumery of the first Klan is the American adaptation of a European harassment ritual called charivari.

White supremacist groups like the Klan have always depended on a myth of consistency and tradition while frequently changing costumes, symbols, and ideology. Understanding the made-up aesthetics of historical hate movements can undercut the fear they demand, and provide us with a useful clarity for today.

In sixteenth-century France, the term charivari designated a form of public reproach that cut across all strata of society. It was a “ritualized mechanism of community control,” as defined by historian Bryan D. Palmer. Charivari was a performance, often carried out at night, and sometimes used as a rite of passage for newlyweds. More often it served as a form of punishment for a violation—legal or otherwise. Commonly conducted by young, unmarried men, a European charivari regularly policed women and sexuality. In a 1990 article in The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, the scholar Loretta T. Johnson notes that victims could be

foreigners who married young local women, women who jilted a well-liked lover to marry richer or older men…young brides pregnant at marriage who made a pretense of virginity, young men who “sold” themselves to rich women or widows, married women proven adulterous, women whose lovers were married men, women who remained unmarried beyond the usual time, cuckolds, and even marriages sterile after one year.

A charivari attack could entail rogue economic justice as well—revenge for a theft, wanton gambling, fraudulent trading, fencing stolen goods, or holding unpopular views. All were punishable by a shivaree, or skimmington, as they were called in England. Though a charivari was often used by the established order to enforce a power structure extralegally, anyone who challenged the social order, rich or poor, could be a victim. This ritual did not require majority consent, and it sometimes ended with the beating or murder of the target. Charivaris created a powerful role in early modern society for listless men, who could adopt the tradition and become the policemen of morality, puckish gang leaders, and unelected vigilantes.

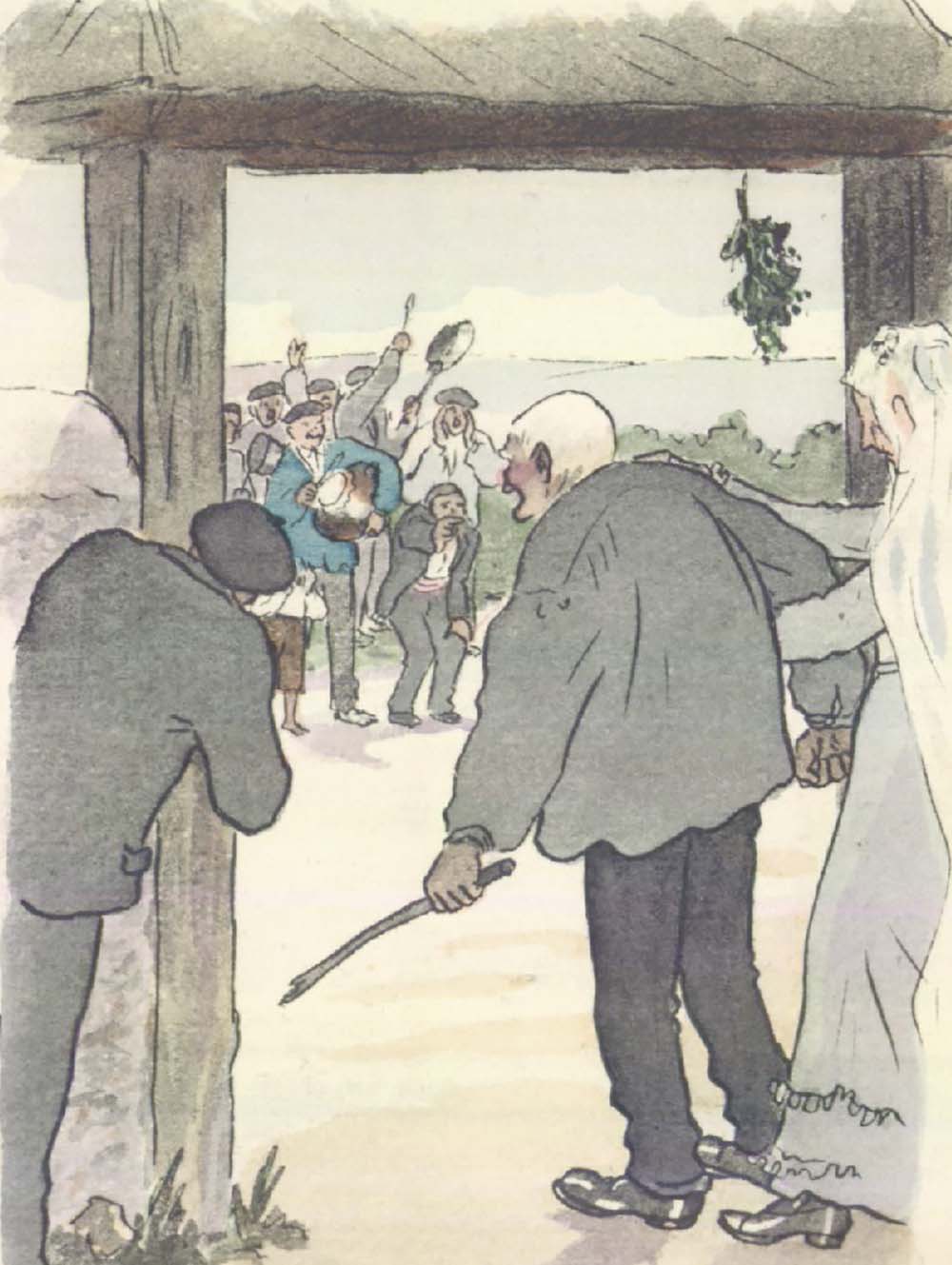

During a nighttime charivari, a band paraded through the dark, arriving at the home of a victim while clanging pots and playing music. Small groups of motivated participants improvised disguises, often parodying aristocratic French fashion trends or mimicking priests’ robes and other church garb—inverting the dress of community authority, turning the world on its head in the carnivalesque tradition. The targeted home was surrounded and an effigy of the resident was sometimes burned—that is, if the inhabitant was not dragged out of bed and beaten or humiliated. Thomas Hardy’s 1886 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge, written after the practice had faded but set earlier, in the mid- to late 1840s, features a charivari wherein a man named Jopp—who harbors a grudge against the mayor, having been cheated out of the position of grain trader—opens intercepted love letters and reads them out loud at an inn. Some of the townsfolk are so scandalized by the mayor’s letters and his implicit affair that word of community retribution spreads around town:

“What do they mean by a ‘skimmity-ride’?” [a visitor] asked.

“O, sir!” said the landlady, swinging her long earrings with deprecating modesty; “’tis a’ old foolish thing they do in these parts when a man’s wife is—well, not too particularly his own. But as a respectable householder I don’t encourage it.”

“Still, are they going to do it shortly? It is a good sight to see, I suppose?”

“Well, sir!” she simpered. And then, bursting into naturalness, and glancing from the corner of her eye, “’Tis the funniest thing under the sun!”

In Hardy’s novel, dummies resembling the couple are paraded through the streets atop a donkey. The mayor’s former lover, Lucetta, is so devastated by the spectacle that she collapses, has a miscarriage, and dies. The mayor does not meet as quick an end, but the humiliation causes him to return to alcoholism and retreat into obscurity. His dying wish is to be forgotten.

The novel’s charivari is a tragedy in the middle of a comedy of errors. The reader understands the complicated truth of the mayor’s love life and of Jopp’s jealousy, but the crowd, too caught up in the electric fun of ritual humiliation, has no incentive to examine its misunderstanding. Siding with power lends people the semblance of power—the false sense of protection of not falling outside the accepted norm.

The individual pain and shaming of a charivari was important in the moment, but its true power was in the way its effects lingered. It was a public spectacle meant to be observed and discussed later on, elaborating a network of unspoken fear and sounding a warning to those who might be next.

Brought to North America by the French, charivaris were recorded from Upper Canada to Louisiana in the mid-seventeenth century. A famous charivari campaign involved the mobbing of Madame Don Andrés Almonester’s home in New Orleans in March 1804. Thousands of people in costumes gathered to punish a rich older woman and her new Cajun husband. The mob was appeased by a $3,000 donation to the city’s orphans.

Decades later, as Black community leaders began to assert their political rights during Reconstruction, racists adopted charivari in the project of reconfirming white supremacy’s grip on power and resources. Ku Klux costuming and amusement helped conceal the group’s true intentions from those in power, while creating plausible deniability amongst their allies. The tactical ambiguity delayed response or retribution while authorities attempted to determine whether the rebels were playing or in earnest. The answer was both.

The Klan went unremarked upon by the Freedmen’s Bureau and remained confined to the Pulaski area until 1868, when the New York World printed a report of Klan violence elsewhere in Tennessee with this bit of commentary: “Outsiders have generally looked upon it as an outlandish but harmless order, whose chief aim was sport and frolic.” They were often called “Kuklux” or a “gang of Ku-Klux” in the papers because, Parsons argues, there is a linguistic distinction between how the first and second waves were described. Ku Klux suggests a disembodied power manifesting, more like ghost visitations or wizard happenings than the actions of an organized political group like the organized, uniformed, 1920s Ku Klux Klan.

The first wave’s costumes and lore became focal points for reportage, which scandalized and intrigued audiences in both the North and the South. Newspapers spread the implied threat of violence, but they also instructed Southern men in how to appropriate the costume and turn into a Ku Kluxer. During 1872 congressional hearing testimony, later published in the KKK Report, one victim described “white gowns…some had flax linen, and red calico, and some red caps, and white horns stuffed with cotton. And some had flannel around coon-skin caps, and faces on…only a little hole at the eyes, not bigger than a man’s fingernail.”

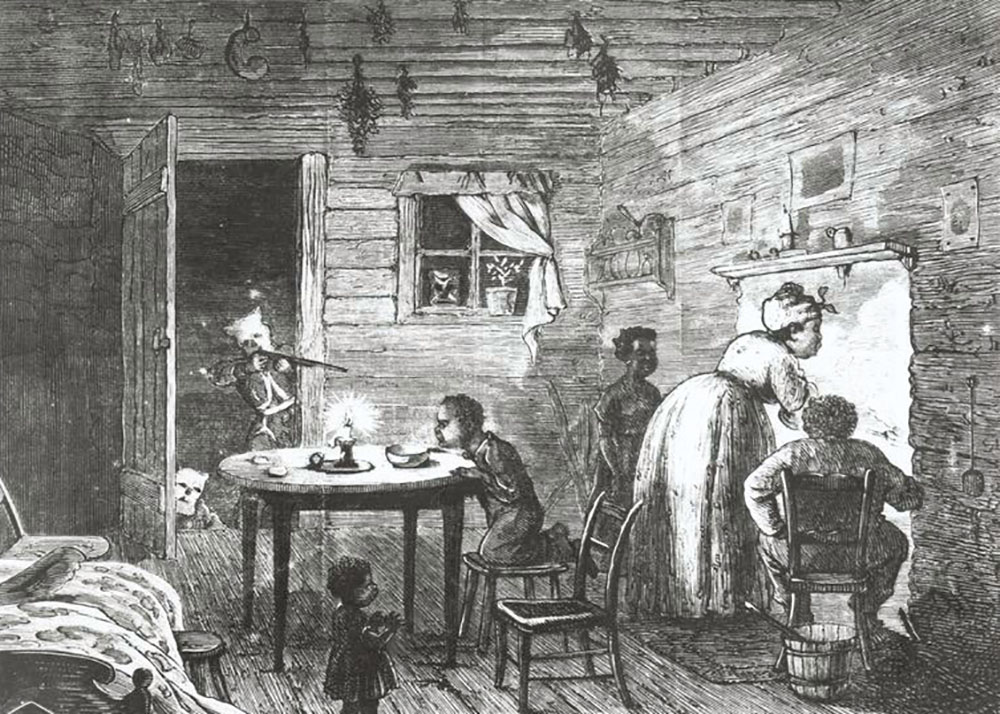

Sensational character backstories were important to the violence. Ku Kluxers would furnish narratives for their costumes so that victims could better report their encounter—and so that the Klan could atomize blame. According to the Klan’s framing, their violence was waged by agents of another realm.

Ku Kluxers frequently claimed to be the walking Confederate dead returning from hell, as historian Stanley Horn explained in his 1939 book Invisible Empire. This lie involved a parlor trick: “The leader of the Klansmen would tell the Negro visited, in a hollow voice, that he was thirsty and wanted a drink,” Horn wrote. After the victim provided a water bucket and drinking gourd, the Ku Kluxer would cast aside the gourd and drink the whole bucket using “a funnel inside his mask connected by a rubber tube to an oilcloth bag under the flowing robe. ‘That’s good,’ he would say, smacking his lips. ‘That’s the first drink I’ve had since I was killed at the Battle of Shiloh; and you get mighty thirsty down in Hell.’” According to Horn, this was a standard routine, “almost the hallmark of a Ku Klux raid—none genuine without it.”

Ku Kluxers in Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia, on the other hand, took a science-fiction approach, often introducing themselves as aliens from the moon. Others dressed in the traditional carnival costumes of domestic animals. Cows, goats, mules with tails and ears—Ku Kluxers hooted like owls, howled like dogs, and, as victims told Congress, “made all kinds of noises, from an ant to a buffalo, and finally ended by bellowing like oxen when they smell blood.”

Many used cork ash to perform their violence in blackface or claimed to be Native Americans. Some purported to be Germans, Mexicans, or Irishmen. Others dressed as plain old circus clowns. When the costumes were donned at night, Ku Kluxers seemed to erupt from an anarchic carnival world, enforcing the extralegal parameters of white supremacy while building a new Southern white male identity.

By 1870 the Klan and similar groups were entrenched in every Southern state, but even in its heyday, the group did not have a well-organized structure. Like the charivari harassment of France, the violence was committed by local groups sharing “a unity of purpose and common tactics,” as Eric Foner puts it in Reconstruction. Such decentralization meant that the Klan could try out a variety of charivari tactics while attempting to brand them as their own. Some witnesses reported Klan parades with a more military than carnivalesque ambiance, describing Ku Kluxers marching in a silent pattern that made their numbers seem multiplied. Others reported that these parades were ill-attended and unimpressive.

Street performance, mysterious letters printed in newspapers, threatening notes left in public, sensational stories of occult violence—larger and faster than the whisper network of early modern Europe—all forms of Reconstruction-era media were exploited to create a paranoid dread that built on the charivari model, enhanced through technologies such as the telegraph, train, and newspaper.

Ku Klux harassment was used for petty local gain and general terrorism, but it was also an assassination program. During Reconstruction, young Black men were becoming political actors with real agency in American public life. If they were too successful or effective, they were murdered by Ku Kluxers, stunting the growth of a community newly freed from slavery and discouraging further political involvement.

The federal government didn’t intervene to stop the Klan until 1870 and 1871, when President Ulysses S. Grant signed legislation designed to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1872 Grant was elected to a second term, and hundreds of Klan members were arrested under the Enforcement Acts, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, which was spurred by the KKK Report. Thousands were hit with fines for “disguise,” or covering the face while out on public highways.

Although the Enforcement Acts were successful in breaking apart what little structure Ku Kluxers had built, key elements of Klan identity continued unabated into the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, albeit in different guises. In 1883, for example, the White Cross Army formed in England, pledging to promote “social purity,” adopting a motto from the legend of Sir Galahad. The movement spread to Australia, Canada, Germany, India, and the United States—an omen that the Christian cross, whiteness, and chivalry would play a larger role in the second Klan movement, in the 1920s.

The White League, also known as the White Man’s League, picked up in Louisiana in 1874, and the Red Shirts harassed freedmen in Mississippi while developing chapters in the Carolinas. Farther north, the White Caps, in Indiana, carried out vigilante justice and lynchings while dressed in masks, hoods, and robes. These groups “likely borrowed heavily from the experience of the Ku Klux Klan, and must have attracted many to the ranks of the movement,” writes Palmer: “From 1888 to 1905, ‘whitecapping’ took up where charivari and the Klan left off.” Adrian Linville reported his attack to the Daily Republican of Rushville, Indiana, in 1908: “The first I knew I heard some men walking out on the porch when I raised up and there were men on both sides of the bed, and they were all masked or had handkerchiefs on but one, and he was blacked,” meaning that he had darkened his face with burnt cork or shoe polish. A similar “whitecapping” group farther west, the Bald Knobbers of Missouri, wore horned black hoods with white-outlined faces.

Street theater proved a refuge for Ku Klux costuming. In the aftermath of St. Louis’ Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the city’s elite rallied around a Ku Klux character adapted from New Orleans’ Mardi Gras. During the strike, a multiracial coalition of St. Louis workers had shut down the city with street parades for nearly a week, humiliating the city’s leaders. Workers demanded an end to child labor, improved wages, and the eight-hour workday. In response, civilians were gunned down and arrested, and the strike was crushed.

In the aftermath, St. Louis’ leaders began an annual Veiled Prophet Parade—a citywide skimmington that marched a Ku Kluxer through working-class neighborhoods atop a parade float, accompanied, in the first year, by an executioner and bloody butcher’s block. Announced as a “Panorama of Progress,” the parade was a dazzling spectacle with thousands of torchlights, candlelit Japanese lanterns, and a fireworks show. Float tableau featured a gigantic silver dollar, “so vast in its dimensions that in a circle cut from its center stood a chair of state in which sat Minerva, goddess of wisdom and protectress of industrial arts from which in their pursuit wealth developed,” wrote the Missouri Republican. The streets were jammed with so many people that, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “at the head of the procession came a squad of policemen, mounted and fully equipped, breaking away the great surging crowd.” The police chief responsible for breaking the strike, John Priest, was crowned Veiled Prophet for the first parade; ever since, the Veiled Prophet’s identity has been kept secret. In St. Louis, Ku Klux vigilantism was now reunited with official civic law.

As it spread, the Ku Klux name was employed in advertising to attract attention, “no matter how irrelevant it was to the product being sold,” Allen W. Trelease writes in his 1971 book White Terror. “Ku-Klux branded everything from baseball teams, to local burlesque shows, to “knifes, paint, pills, a circus act, and a ‘Ku Klux Smoking Tobacco,’ containing the ‘spirits of a hundred faithful KKKs.’” Even after the movement became illegal under Grant, the naming conventions persisted. The fad of turning c’s to k’s took on Ku Klux connotations.

Impressed with the results of the Veiled Prophet Society’s parade and its accompanying debutante ball, business leaders of Kansas City, Missouri, began a knockoff group called the Priests of Pallas in 1887, advertised as the Kansas City Karnival Krewe. In 1894 the Priests elected a parade leader called King Ki Ki and advertised the festivities as a “Karnival Klimax.” While the Kansas City Public Library denied the connection between King Ki Ki and the Klan, in a blog post about this history, it noted that, “Some parade participants wore stereotypical ethnic costumes and blackface makeup to impersonate people of color.” Audience members of the 1880s would have understood the subtext of a Southern-style “Kansas City Karnival Krewe.” The intense violence and threat of the first Klan lingered in public consciousness while disavowing any influence.

The Priests of Pallas are no more, and the Veiled Prophet Ball continues by invitation only, but contemporary visitors of the French Quarter can see the disguised Captain Bathurst of the Rex Krewe in person during Mardi Gras. The Rex Krewe is composed of a secretive membership that was restricted to those of “European ancestry” until 1991.

During the second wave in the 1920s, the Klan’s charivari costumes were replaced with what we now associate with the Klan: white robes, white steepled hats, burning cross. That Klansman has become a hated icon in American culture, dominating the archetype of open white supremacy, but as we can see in the Klan’s European origins, this ideology shifts and changes its costumes constantly. Many of the terrorist tactics remain the same, wielded by antisocial morality police and defeated racists alike.

Today, the last century’s Klan characters have been replaced by paramilitary ensembles influenced more by Call of Duty than by Sir Walter Scott. But male aimlessness, confused chivalry, and violent racial and gender performance remain a mainstay. The names, lore, and costumes change, but the media objective remains the same: convey the threat of genocidal white supremacy while playing dress-up.