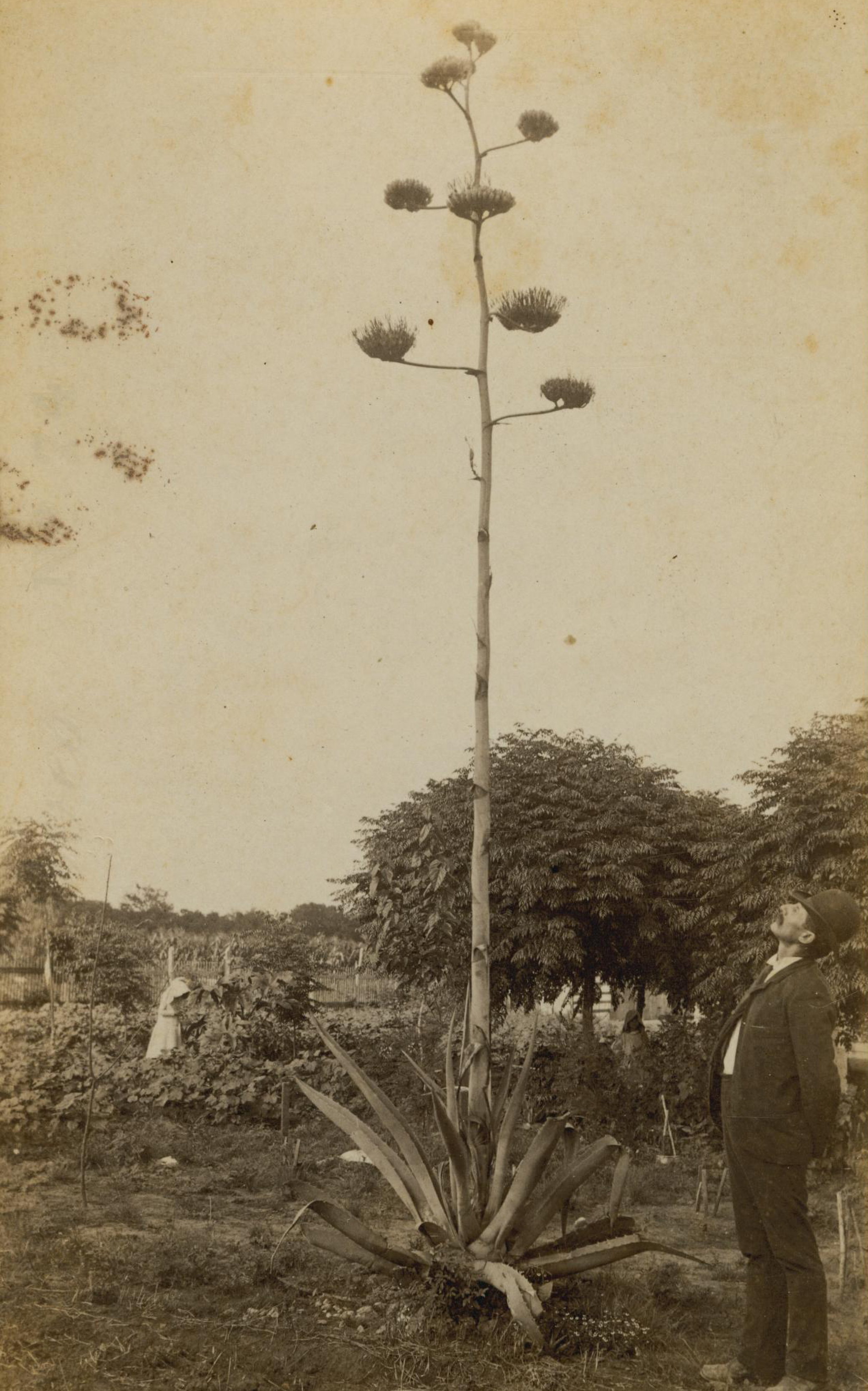

Photograph of a man standing by a century plant, c. 1889. Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Reies López Tijerina never forgot the first time that he visited Jesus. The visit occurred during a dream when he was only four years old. As he liked to recount, he had gone to bed extremely hungry and deeply hurt one evening. The son of Texas migrant farmworkers, Tijerina had been upset to discover that dinner consisted of only half a cup of tea brewed from the bark of a pecan tree. He was too young to understand that, as the Great Depression raged, the family had no money with which to buy food. That night, the exhausted and probably malnourished little boy fell into such a profound sleep that his family became convinced that he was dead or dying. His mother sent his brother Anselmo, the eldest and Tijerina’s senior by six years, to go fetch a doctor. But Tijerina woke up the next day not only fully recovered but convinced that he had seen heaven and walked with Jesus: “He took me by the hand and was showing me great green pastures and a garden full of flowers, a beautiful place, and then he was pulling me along in one of those small, little toy wagons, a red one, you know—I never did have one—he was pulling me along in that.”

In another recounting, Tijerina remembered that he had done the pulling. Otherwise, the central elements of his story remained remarkably consistent over the years: the tea, the hunger, the little red wagon, and the presence of Jesus. Tijerina also repeatedly labeled his deep sleep a “death,” a word that suggested his awakening was akin to a resurrection.

In a later interview, Tijerina made sure that no one missed the story’s strong connection between himself and Jesus. After he woke up from his deep sleep, Tijerina explained, his uncles used to say about him, “There goes the dead boy…there goes the resurrected boy.”

As this oft-revisited childhood memory suggested, Tijerina’s earliest years were defined by severe poverty and intense religiosity. His first name was a gift from his mother, who wished to name her son after Jesus Christ, the King of Kings, el Rey de los Reyes. According to the baptismal registry of the Church of the Annunciation in St. Hedwig, Texas, just east of San Antonio, Reyes López Tijerina was born in that town on September 21, 1926. Tijerina, however, always maintained that his mother gave birth to him atop a pile of cotton sacks along the edge of a field in Falls City, Texas, some forty miles to the south. Perhaps his Spanish-speaking parents, Erlinda López and Antonio Tijerina, had a difficult time communicating with the church’s pastor, the Reverend S. Przyborowski. In a way, the discrepancies hardly matter. Whichever town marked his actual birthplace, and whatever spelling his parents intended for his name, the meager circumstances of his entry into this world were clear enough. Like so many other Mexican-descent children in the United States at the time, Tijerina was born poor, a member of a despised racial minority, and, like his parents before him, seemingly destined for the backbreaking life of a migrant farmworker.

Yet looking back upon the same set of circumstances, Tijerina saw in himself a boy and then a man destined for greatness. God told him so in dreams and via other signs from above.

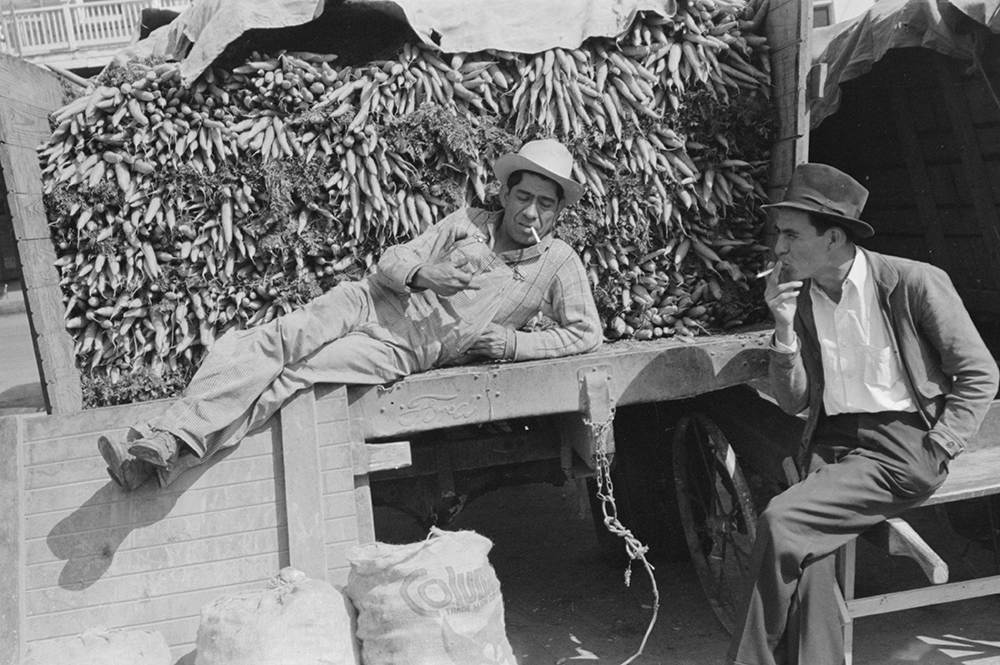

Tijerina’s early years coincided with the worst economic downturn in U.S. history. Migrant families like the Tijerinas had barely scraped by during more prosperous times. During the 1930s, their plight became truly desperate. Hunger and want stalked Tijerina’s childhood. As a boy, owning the little red wagon that appeared in his dream was just that—a dream. He played instead with what the jackrabbits left behind, their cagarutas, or droppings, which he and his brothers used as marbles. Shoes were almost as much of a luxury as toys. While on the migrant trail, home meant a shifting array of one- or two-room wooden shacks or adobe huts that his parents rented on someone else’s property. Starting as a little boy, Tijerina worked in the fields alongside his parents and elder siblings. “We moved from town to town looking for work,” he recalled. “Poth, Whiteface, Lubbock, Wilson, Levelland, Floresville. We picked beans and melon, we picked cotton, twenty-five cents a hundred pounds, chopped cotton, ten cents a row, topped turnips and hoed onions and cultivated broom corn and shelled pecans.” Off-season, the Tijerina family returned to San Antonio. There, Tijerina and his brothers scoured the city dump to gather anything of value for resale, from scrap iron to glass bottles.

In Tijerina’s memory, his mother stood out as a physical and spiritual amazon, a tremendous source of comfort in an otherwise cruel world. Tijerina credited her with giving birth to all of her children without the aid of a midwife or even the presence of her husband. Poverty took its toll: three of his siblings died in infancy. Nonetheless, as he liked to relate, after giving birth to him, his mother jumped up from that pile of cotton sacks and, passing the newborn Reies to an older child, resumed working. Tijerina remembered Erlinda López Tijerina as almost superhuman, catching poisonous snakes using only a stick and her own lightning-quick responses; selling them apparently brought some extra income. His mother was so strong, Tijerina insisted, that she routinely carried hundred-pound sacks of cotton on her back, so strong that she even carried her husband to and from the fields when he was unable to walk himself. Why his father could not walk at times was unclear: Tijerina once asserted that some Anglo Americans had slashed his father in his thigh instead of paying him wages; another time he wrote that his father suffered from terrible calluses on his feet, and another time that his father’s feet were so bad that he had amputated toes. Consistent in his memory, however, was the notion that his father was a weak and timid man compared to his powerful mother.

“My father feared the Anglos very much,” Tijerina once wrote; “my mother did not fear them.”

Erlinda López died when Reies was just seven. One day near Coleman, Texas, Tijerina later explained, the family was “heading toward the cotton fields in a Model-T, [when] my dad had an accident and the car overturned and my mother hurt one breast. Later they operated on her in San Antonio, Texas, at that city’s Robert Green Hospital [but] it [the injury] became cancer, or more precisely, gangrene, and from that she died.” While Tijerina was uncertain about the exact cause of her death, he never forgot listening to his mother’s cries of agony before she died; the family was too poor to buy painkillers for her. Always during times of trouble and confusion, he asserted, he would recall her valor and spirituality. “My mother…planted in my blood, soul, and spirit, the seed of justice, of truth, and of mercy,” Tijerina wrote many years later. “She was great, robust, and very brave.”

The family suffered greatly from her absence. Left a widower with seven children, Antonio Tijerina immediately asked a neighbor to raise the youngest, an infant named Cristóbal. Still, he had troubling providing for the remaining six: Anselmo, Margarito, Ramón, Reies, Maria, and Josefa. On occasion, Reies’ two sisters were farmed out to relatives. Sometime around 1940, Antonio Tijerina began to travel with his family to Michigan to cut beets, following a well-established migrant path that bisected the country north to south. For the next several years, the family traveled back and forth between Texas and Michigan.

The poverty that robbed Tijerina of his mother also robbed him of an education. His scholastic career was short and sporadic. Two surviving San Antonio elementary school report cards indicate that Tijerina enrolled in elementary school three times, once every year at the ages of ten, eleven, and twelve. In a pattern that plagued migrant families, he repeatedly dropped out to return to work. Tijerina often estimated that he never gained more than a third-grade education, perhaps six months in total. The report cards also listed four different home addresses over the course of three years, strongly suggesting that, even when living in San Antonio, the Tijerina family remained on the move, unable to pay the rent.

Despite these obstacles, the boy whom the teachers called “Ray” earned top marks during his limited schooling. He did so at a time, moreover, when even the best-intentioned teachers assumed that children of Mexican descent were culturally handicapped if not mentally deficient. The Americanization of “Reies” to “Ray” on the report cards underscored the limited value that mainstream society then placed upon Mexican culture and the Spanish language. While Tijerina never commented directly on the imposed name change, he did like to recount how his older brother Ramón, after being spanked for speaking Spanish in the classroom, left school that day in anger and never returned. Poverty reigned as only one of the injustices that framed Tijerina’s young life.

Racism flourished in the intense anti-Mexican atmosphere of Depression-era Texas. Across the country, the economic crisis spurred anger toward Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans alike who stood accused of taking jobs away from “real” Americans. This animosity culminated in a series of repatriation and deportation campaigns whereby local authorities ejected tens of thousands of Mexicans and, in some cases, their American-born children from the country. Texas formed an epicenter for these efforts. One estimate is that more than half of all the people sent to Mexico during the era’s deportation and repatriation campaigns were from Texas. The virulence and staying power of anti-Mexican sentiment throughout the decade almost certainly contributed to the Tijerina family’s decision to move to Michigan at least on a part-time basis. Indeed, American citizenship offered the Tijerina family only one tangible benefit during the 1930s: Anselmo Tijerina, Reies’ oldest brother, landed a job working for the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps.

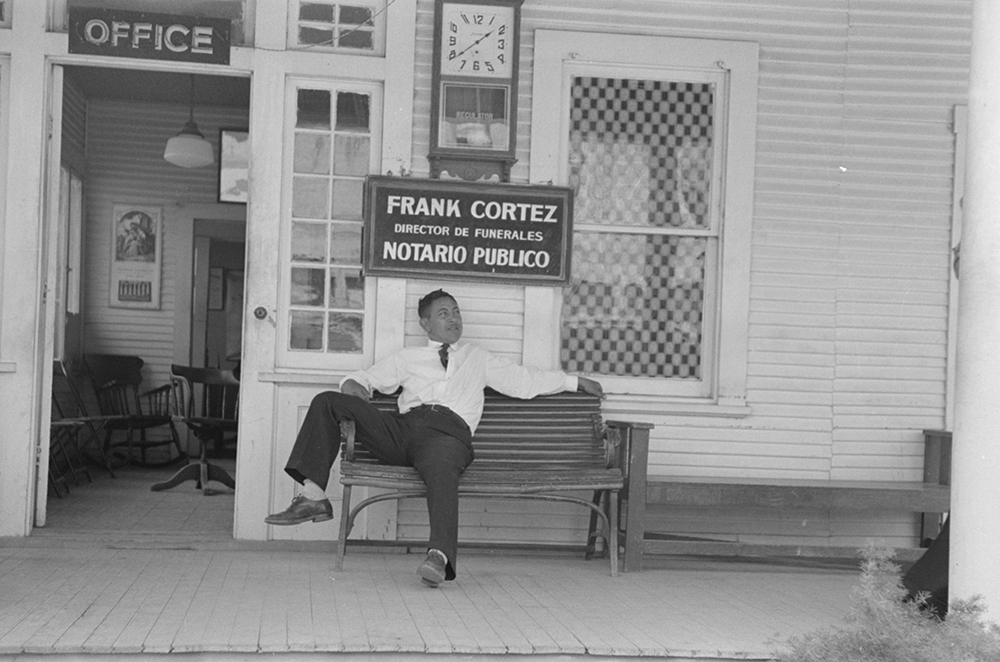

Although the Depression marked a low point in race relations between majority society and ethnic Mexicans, strong antipathy toward Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants had a much longer history in Texas. Starting with the establishment of the independent Texas Republic in 1836, intertwined racial and economic hierarchies cast Spanish speakers in Texas as a politically suspect, racially stigmatized, and economically exploitable minority. Although many Tejanos (Mexican Texans) had supported Texas independence, afterward they soon lost their political standing and, within a few decades, most of their economic fortune. Key here was the gradual but inexorable loss of land. The legal and extralegal dispossession of property holdings that began in Texas was to have its echoes elsewhere across the new American Southwest after 1848. As David Montejano summarized in his study about south Texas following the American takeover, “Taxes, mortgage debts, legal battles, the effects of the erratic cattle and sheep market, outright coercion and fraud, as well as the cash offer of land speculators, all combined to reduce the number of Mexican landowners.”

Consequently, few Mexican Texans were in the position to benefit from the economic shifts that followed the American takeover. Before 1836, Mexican Texas had been a place where Spanish-speaking people made a living mostly through ranching and by growing their own food through small garden plots. It turned out that the vast, flat plains of the state proved as ideal for growing crops as for grazing animals, especially after the introduction of commercial irrigation systems. By the start of the twentieth century, agribusiness had become a mainstay of the Texas economy, along with a booming cattle industry. As a mostly landless population, however, people of Mexican descent, whether they were born north or south of the Rio Grande, rarely rose above the position of farm laborer in the state’s economic hierarchy. To agribusiness, the value of Mexican-origin people was that they kept hiring costs down. A 1928 advertisement boasted as much. Showing seven dark-skinned men standing with their hoes in front of row upon row of cabbage plants that faded into the distance, the accompanying text bragged, “mexican labor—Cheap and plentiful—wages $1.50 a day, ten hours—efficient, loyal and plentiful.”

Just as the advertisement drew no distinction between immigrant and native-born, neither did the tremendous amount of violence, much of it officially sanctioned. First formed in the 1870s, the Texas Rangers acted as “an army of occupation” in south Texas, dispensing their form of vigilante justice against Mexicans and Mexican Americans alike. One of the worst episodes occurred between 1915 and 1917 when Texas Rangers and other law enforcement agents aggressively responded to a far-fetched plan to return the U.S. Southwest to Mexico. Although the Plan de San Diego attracted only a few adherents on either side of the border, law enforcement engaged in suppressing this perceived threat indiscriminately killed as many as five thousand people of Mexican descent in Texas over this two-year period. As late as 1922, just four years before Tijerina’s birth, the New York Times noted in an oft-cited editorial that in the Texas border region, “the killing of Mexicans without provocation is so common as to pass almost unnoticed.” At the time, Texas was home to tens of thousands of members of a reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan. Not until the end of the decade did segregationist practices imported directly from the South begin to replace violence as the new means of keeping the state’s Mexican-origin population contained.

Although much of this violence predated Tijerina’s birth, family lore and Texas history often met and merged in his recollections. He looked to his paternal grandfather, Santiago Tijerina, to trace a genealogy of persecution and heroic resistance within his own family. According to Reies Tijerina, both the Tijerina and López families had been landowners until the arrival of the Americans. As he often recounted, one day the Texas Rangers murdered his great-grandfather, a terrible crime that young Santiago witnessed. In Reies’ estimation, Santiago went on to become a “lion” of a man, someone who spent the rest of his life fighting against an oppressive racial order. According to his grandson, Santiago escaped across the border from the Texas Rangers three times and, when fleeing was impossible, fought them with his bare fists. He even survived vigilantes stringing him up in a tree. Luckily for him, the story went, a judge told the crowd that they had the wrong man, and he was cut down.

In contrast, Reies Tijerina seemed to view his father’s life as a cautionary tale of the failure to resist injustice. His son maintained that Antonio Tijerina suffered more than a knife wound to the thigh. As a young family man, Reies wrote, Antonio had tried to make a living as a sharecropper, but three times he was run off the property before being paid at the end of the harvest. The last time, the landowners ordered him at gunpoint to depart the field and, when Antonio refused, dragged him away by a rope. Even after his father had descended the economic ladder from sharecropper to migrant worker, his son recalled, Antonio still had to worry about anti-Mexican hooligans. Another of Reies Tijerina’s childhood memories was of his father and fellow fieldworkers keeping close watch, especially after payday, in case members of the Ku Klux Klan decided to visit them.

Although impossible to confirm in every detail, these family narratives were in keeping with the violence that marked Texas during the first decades of the twentieth century. They also injected a mythic quality to Tijerina’s own origin story. In revisiting stories about his youth, Tijerina repeatedly cast himself as a fighter in the mold of his paternal grandfather and his own mother. For example, later in life, he recalled challenging a teacher who proclaimed the United States the home of the brave and the land of the free. After all, it was not a land of freedom for people like him!

Adapted from The King of Adobe: Reies López Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement by Lorena Oropeza. Copyright © 2019 by Lorena Oropeza. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.