Calling Dr. Death (1943), Random Harvest (1942), and I Love You Again (1941) all depend on amnesia for their plots.

If we want to understand continuity and change in film history, it’s useful to assume that cultural attitudes, memes, sticky ideas, and the like serve as materials for movie making. They’re selected and sculpted by filmmakers and the pressures of cinematic tradition. They’re modified by context. As in other art forms, filmmakers swipe cultural elements and submit them to the demands of their craft.

Take amnesia. With so many 1940s characters suffering from it, we’re tempted to interpret their plight as reflecting wider forces. One critic proposes that films featuring amnesia (like movies about angels and ghosts) were the culture’s way of offering solace to those who lost loved ones. A more academic critic might suggest that broader anxieties within American society led to a fascination with “a loss of cultural memory.” But exactly how the U.S. population, 130 million strong, induced Hollywood to make such movies is never explained.

There’s no disputing that a great many 1940s Hollywood films involve amnesia—over seventy, by one count. But we can find over sixty amnesia-driven releases in the 1910s, about fifty in the 1920s, and at least forty in the 1930s. Amnesia is rare in real life but common in movies.

And not only movies. It’s a treasured plot resource throughout the world’s literature. Clinicians may deplore the fact that creative writers almost never represent amnesia accurately, but fictional versions answer to narrative demands, which often care little about realism. Movie amnesia is only one step above the “magic forgetting” we find in folk tales. Folklorists have compiled catalogs of amnesia motifs, such as “forgotten fiancées” and “forgetting by stumbling.” Great authors from Homer and Shakespeare to Dickens and Balzac have had recourse to amnesia, and it has been a common device for modern writers, high and low. The river Lethe, the lotus fields of the Odyssey, the laudanum that causes memory loss in The Moonstone, the problems plaguing the protagonist of Memento (1999)—across the ages, memory breakdowns afford storytellers a wide range of creative options.

I suggest we be cold-blooded and take amnesia not as a symptom of audience anxieties but as a reliable narrative device. News of battle injuries and home front breakdowns offered forties filmmakers a realistic alibi for stories of memory loss. Whatever sympathies a screenwriter may have had for wounded vets or tormented housewives, craft conventions made amnesia an attractive option.

For instance, stories demand gaps in knowledge. One way to spread fruitful ignorance is to create characters who don’t recognize themselves, or who can’t recall things they’ve done, or who can’t remember their loved ones. Amnesia generates curiosity (What has made X forget?) and suspense (Who will X turn out to be?). Amnesia can justify flashbacks and can cover time gaps later to be revealed as important (Calling Dr. Death, 1943). A lost identity can create dramatic crises, as when the protagonist in Random Harvest (1942) finds that for years he has led a double life. Amnesia can also generate changes in character. Sullivan’s Travels (1942) shows a befuddled film director sentenced to a chain gang. Had he remembered who he was, he would not have learned about life at the bottom of society.

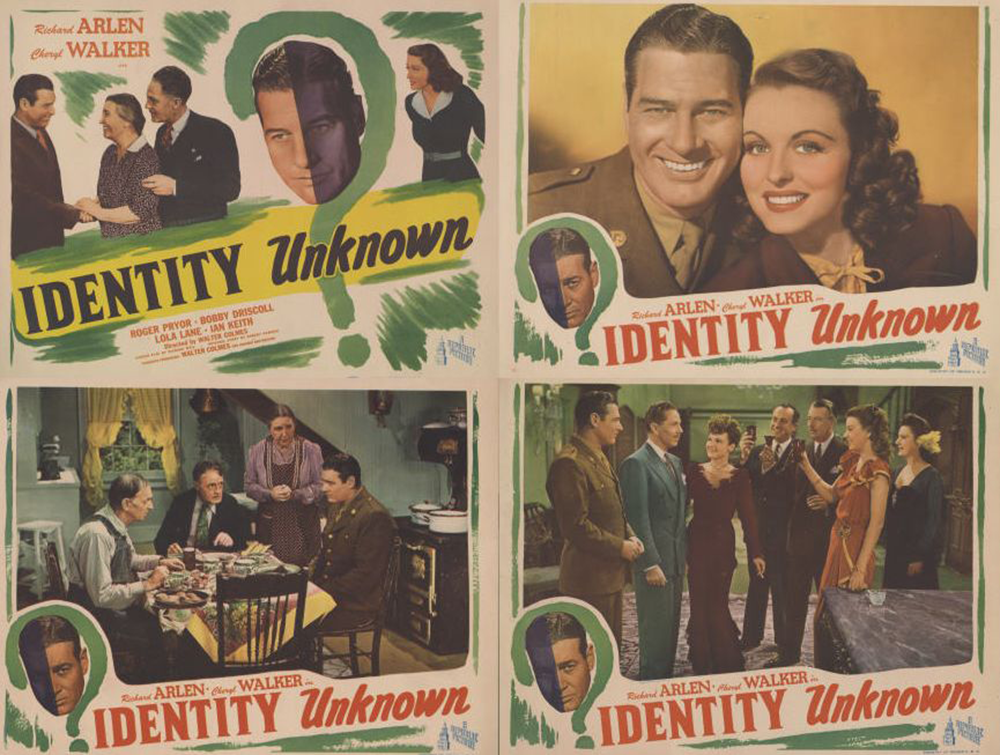

As a momentary device, amnesia can prolong situations and trigger humor or tension. As a more basic premise, it can turn an entire plot into a search. In Identity Unknown (1945) an amnesiac pilot tries to find himself by tracking down the families of all the buddies lost on his mission and asking, by cruel elimination, if anyone recognizes him. Amnesia can be contagious too. The most florid case in Love Letters (1945) strikes a young wife because of a traumatic murder, but forgetting haunts other characters as well.

Filmmakers were well aware of using the ailment opportunistically. “Coming up,” wrote a columnist, “is another picture about amnesia, a common malady these days.” A review criticized Street of Memories (1940) for adhering to “the outdated amnesia formula.” The pressure was on filmmakers to freshen up this old device, and several did. Love Letters, noted Variety’s reviewer, “employs such plot oldies as the Cyrano de Bergerac and the amnesia adventure as foundation, but develops a pattern of gripping interest from them.” In I Love You Again (1941) a prissy small-town Rotarian, conked on the head, realizes he’s had amnesia for nine years. He was originally a slick con man, and now, coming home, he must pretend to still be the hick he temporarily was. I Love You Again was praised for finding a new twist on the cliché.

This isn’t to say that movies’ version of amnesia is sheer plot contrivance. Lost memory has its own appeals. It’s fun to think about. It generates sympathy for its victim and raises thematic questions about what is stable in personal identity. Through the device of amnesia, films can conjure up serious concerns about returning veterans. From the standpoint of craft demands, though, 1940s social conditions can be used to realistically motivate this conventional device. What might be taken for passive reflections of a zeitgeist can better be seen as filmmakers’ fitting bits of immediate actuality to narrative needs.

Back in the 1920s, writers began to argue that Hollywood had created a vivacious art form that fully earned its name, “moving pictures.” Gilbert Seldes, in his influential book The Seven Lively Arts (1924) argued that lowbrow mass entertainments had a spontaneous energy that genteel fiction, poetry, and theater lacked. On the screen, fine as Griffith and DeMille were, it was Mack Sennett’s slapstick comedies, with pratfalls and careening chases, that best fulfilled cinema as an art of movement: “Everything capable of motion set into motion.”

From this standpoint, the coming of sound could only seem a setback. Movies became more dialogue-driven, even stiffly theatrical. Seldes claimed, though, that Hollywood regained its footing in the mid-1930s. The gangster films in particular had achieved “the perfection of the silent movies with dialogue superimposed.” Talkies had recovered a distinctive cinematic pace through merging vigorous action with terse conversation. Critic Otis Ferguson celebrated the crisp, thrusting rhythm of comedies, social dramas, and adventure films.

If there is any one thing that the movie people seem to have learned in the last few years, it is the art of taking some material—any material, it may be sound, it may be junky—and working it up until the final result is smooth, fast-moving, effortless…Whoever started the thing in the first place, Hollywood has it now, and Hollywood speaks a different language.

The key, Seldes noted, was not the story itself but “the way the story is told, which is by movement.”

That movement need not be extreme, as F. Scott Fitzgerald pointed out in his unfinished novel The Love of the Last Tycoon. In one scene, studio boss Monroe Stahr explains to a snobbish writer from the East how to grab the viewer’s interest. Stahr sketches a scene: A young woman hurries into an office and furtively burns a pair of black gloves. The phone rings, and when she answers she says she’s never owned a pair of black gloves. Now Stahr reveals that there’s a man already in the office watching her.

The hypothetical sketch isn’t a virtuosic visual turn like a Keaton gag. It depends on a situation that’s articulated in a bit of dialogue, a few hand props, and simple bits of business. No fights or pratfalls here, yet the action summons up curiosity, suspense, and surprise. Stahr’s eastern writer is intrigued. “Go on. What happens?” “I don’t know,” says the tycoon. “I was just making pictures.”

Fitzgerald had worked on screenplays, and like his peers he was aware of the power of visually grounded narrative. In 1937 Frances Marion, a distinguished MGM screenwriter, published a how-to manual that explained everything from double plotlines and character arcs to trick transitions and swift pacing. A year earlier, the journalist Tamar Lane had written a discerning book about the new technique of sound pictures. Lane surveyed a host of creative options, including plot twists, montages, and clever exposition. Clearly, filmmakers of the mid-1930s were confident that sound could be assimilated into their tradition of pictorial storytelling.

We can think of that tradition as a vast set of collective solutions to basic problems: controlling exposition, picking out protagonists, building up drama, sustaining suspense, and so on. By the end of the 1930s, several other collective problems had been solved. Sound technology was improving immensely. Multichannel recording was established, microphones became more sensitive, and fine-grain print stock began to be used during recording, mixing, and printing for final release. Filmmakers had also created a new genre, the musical, and major variants—the revue, the backstage story, the musical as a romantic comedy with songs—had been mapped out.

Thanks to both dramaturgy and technology, then, most 1930s films preserved the fluidity of 1920s storytelling. The action was usually presented chronologically and objectively, and the characters were typically fixed, consistent, and transparent in their traits and motives. Accordingly, the narration was reliable. Except in the case of mysteries, the viewer could take what was shown at face value. The stability of this storytelling system was later celebrated by critic André Bazin, who maintained that studio narrative technique had reached a point of perfection by 1938–39.

In creating this stability, though, filmmakers tended to iron out aspects of 1920s cinema that Seldes and Ferguson had played down. Silent filmmakers had pioneered some flamboyant storytelling techniques. Many 1920s films resorted to self-conscious devices, and some flaunted them to an extreme degree. Such straying into stylization was mostly suppressed after the coming of sound. True, talkies continued to employ the montage sequence, a string of rather abstract images portraying a place or summing up a process (train trip, business success, changing seasons). But most 1930s scenes relied on the sharp, sober presentation of dialogue and behavior exemplified in Monroe Stahr’s phone-call intrigue.

Making pictures, as Fitzgerald’s mogul conceived it, was what Hollywood had learned how to do. But too much repetition wasn’t good for business. Along with stability came a steady pressure toward novelty. As happens in any period, some filmmakers sought to be original in a noteworthy way.

What new things might be accomplished in the 1940s? Well, filmmakers could consolidate and expand certain options already developed. Thirties screwball comedy could be sustained in Ball of Fire (1942), The Major and the Minor (1942), and other pictures. The A-level Western, exemplified by Stagecoach (1939) and Dodge City (1939), became the “super-Western” of Duel in the Sun (1947) and Red River (1948). Opulent costume dramas and turn-of-the-century Americana persisted through the decade. In the face of slumping box office in the late forties and early fifties, biblical spectacle was revived in Samson and Delilah (1950), David and Bathsheba (1951), and Quo Vadis (1951). Comedy teams like Abbott and Costello and Hope and Crosby recalled the heyday of the Marx Brothers but brought their own sensibilities to the genre. New trends in all areas should be encouraged, noted one commentator: “Without such pictures, there would be no progress in picture making, no competition in picture making, and no fun in it at all.”

Forties musicals epitomize the urge for constant, expansive novelty. Some musicals took on a populist or nostalgic tenor (Meet Me in St. Louis, 1944; State Fair, 1945), while others benefited from merging conventions with the biopic (Yankee Doodle Dandy, 1943; Night and Day, 1946). Production values became more flamboyant thanks to rich Technicolor, bigger budgets, and ambitious special effects. Esther Williams’s aquatic spectacles, the banana ballet of The Gang’s All Here (1941), the sailors’ urban adventures in On the Town (1949), and Fred Astaire’s pipe-cleaner body stretching in slow motion in Easter Parade (1948) made even the excesses of 1930s musicals look staid. Still, these sequences had their roots in earlier song-and-dance extravaganzas. Astaire’s signature special-effects cadenzas, for instance, were ambitious revisions of his “Bojangles of Harlem” number in Swing Time (1936).

Beyond revamping older traditions, filmmakers could push some boundaries. Could movies become sexier? Yes. The Breen Office, the industry’s censorship agency, was letting its guard down, and David O. Selznick, Preston Sturges, and Howard Hughes, among many others, found ways to heat up the screen. And could movies tackle social problems like racism and anti-Semitism? Yes. A wave of “message pictures” garnered prestige and box office revenues. “Exploitation pictures,” once relegated to Poverty Row, went upmarket as studios based combat pictures, spy films, and crime movies on the day’s headlines. The Lost Weekend (1945), The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), Naked City (1948), Home of the Brave (1949), and other films were rewarded for risky themes and more adult attitudes.

Most films in these genres and cycles display Ferguson’s “smooth, fast-moving, effortless” technique. Yet the forties demand for movies, almost any movies, yielded an opportunity to experiment with narrative as well. In conditions that favored risk taking, some filmmakers tried revising the storytelling conventions they inherited. That meant, in many cases, returning to possibilities sketched in the 1920s—greater subjectivity, playing with time and viewpoint, a willingness to create highly stylized narration. And revival led to revision. Filmmakers, recognizing the new demands of sound cinema, could develop those tendencies in ways unavailable to silent movies.

Exploration and variation come with the territory. A filmmaker deploying any technique is forced to choose among fine-grained options. If you opt for flashbacks, will they be memories or testimony? Will they be anchored in a single character, or will they provide different characters’ perspectives on a situation? Will the flashbacks be fully informative about past events, or will they leave out crucial items—to be provided, perhaps, by other flashbacks? Will the flashbacks be arranged chronologically or shuffled out of order? If you choose a voice-over, will it be subjective, flowing inside a character’s mind? Or is it more detached, recounted by the character at a later time? Or might the voice-over issue from an external narrator? Will it hold back information we need to follow the action? Apart from forced choices, there’s the need for novelty. After many filmmakers have embraced one option, how can the next film distinguish itself?

Which is to say that many forties filmmakers constantly set themselves fresh creative problems. This effort made filmic storytelling rich, complex, and engaging. By consolidating new narrative norms, filmmakers encouraged further innovations. It’s this flowering of forms that partially explains the “thickening” we sense in forties classics, their demand that we rewatch and discuss them.

Bazin thought the turn of the decade marked the beginning of a new cinema style, on display in the deep-focus, long-take works of Orson Welles and William Wyler. It was the beginning of something else as well. From 1939 onward, collective efforts at narrative innovation wound up recasting the entire Hollywood tradition.

Reprinted with permission from Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling by David Bordwell. Copyright © 2017 by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.