Leech Finders, by George Walker, 1814. The New York Public Library, Rare Book Division.

First, Do No Harm…Oh, Never Mind

Some surgical innovations were skin-crawling but brilliant. In the Samhita, written by Indian surgeon Sushruta in 500 BC, he recommended, “Large black ants should be applied to the margins of the wound and their bodies then severed from their heads, after these have firmly bitten the part with their jaws.” Voilá. Insect’s mandibles as natural staples for wound closure. Genius, right?

But many surgical history books tell of the not-so-ingenious stories of surgically altering what probably shouldn’t be altered. Stuttering is a classic example. In the nineteenth century, German surgeon Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach would cut out a triangular wedge near the root of the tongue to cure stuttering. Others tried to “resize” the tongue, or cut the frenulum, the delicate piece of tissue between the tongue and the floor of the mouth. None of these procedures worked.

In 1831 a Mr. Preston decided that it would be a good idea to tie off a carotid artery on the side where a patient had a stroke. There’s just one problem: Strokes often occur from lack of blood flow to the brain. Trying to help by cutting off the blood supply is like helping a drought by telling a rain cloud to do business elsewhere. The patient somehow survived. Preston also recommended that perhaps both carotid arteries be tied off for treatment of strokes, epilepsy, and insanity. Thankfully, no one took his advice.

As the fear of autointoxication—the theory that the normal end products of digestion contain poison—grew, many tried to cure constipation with myriad devices and purgatives at the turn of the twentieth century. One British surgeon, Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, took it a step further. He cut out the colon altogether. He performed more than a thousand colectomies, mostly on women. Surely, slow colons were the cause of women’s mental shortcomings like stupidity, headaches, and irritability. Luckily, you can snip out your colon and survive, but you’ll likely have the side effect of lots of diarrhea. Like most functioning parts of your body, colons are better left intact.

Lane also was a proponent of fixing misplaced organs. Yes, you heard that correctly. In the early twentieth century, many believed that vague abdominal and whole-body discomfort could be due to “dropped” or “misplaced” organs. The kidney was perhaps the most misplaced organ of all time. Lane blamed dropped kidneys, or nephroptosis, for causing suicidality, homicidality, depression, abdominal pain, headaches, and the more obvious physical symptoms of urinary problems. Removing even one kidney killed too many patients, so surgeons instead performed a “nephropexy”—more or less tacking kidneys back in place using sutures and occasionally rubber bands and wads of gauze. By the 1920s, this procedure was falling out of favor with some surgeons claiming that “the most serious complication of nephroptosis is nephropexy” and that urologists seemed to have “an orgy of fixation of kidneys.” (To be fair, part of a urologist’s job is to fixate on kidneys, but the orgy part was a bit dramatic.)

Kidneys weren’t the only body part atrociously fiddled with by surgeons. Tonsils, the glands at the back of the throat, were also removed in excessive numbers in an effort to put a stop to all childhood infections—a well-meaning but misguided aim. Of course, the tonsillectomy has its place as a modern-day therapeutic in cases of sleep apnea and recurrent tonsillitis, but as a last resort. Most would be shocked that in 1934 a study in New York showed that of one thousand children, more than six hundred of them had had tonsillectomies. They weren’t risk-free surgeries, either; many children died annually from the procedure.

Arsenic

Meet Mary Frances Creighton—a wife, sister, and mother with a talent for getting away with murder. The first time she killed, the victim was her mother-in-law in 1920. People thought the wealthy forty-seven-year-old woman died of ptomaine poisoning. But Mary had fed her some toothsome hot cocoa just before she began to violently vomit. She was dead within hours. In 1923 Mary struck again. She’d persuaded her teenage brother, Charles, to move in with her and her husband, even feeding him chocolate pudding before bedtime. Charles fell sick with stomachaches and a dry mouth. He died a rather horrible death soon after, stricken with vomiting and shaking.

It was blamed on a bad stomach virus. But how convenient that Mary had just become a beneficiary in a $1,000 life insurance policy for Charles. The police were alerted via an anonymous letter that Mary Frances was a liar and the boy a victim. Bodies were exhumed, and forensic chemists tested the bodies of both Charles and Mary’s mother-in-law. The answer? Arsenic.

Better known for its ability to kill than heal, arsenic is a potent liver toxin and a carcinogen. A lethal dose (around 100 mg) will usually render the victim dead within several hours. From the Middle Ages until the turn of the twentieth century, arsenic was fondly known as “the king of poisons,” “the poison of kings,” and “inheritance powder.” Even Hippocrates knew of its toxicity in ancient times, describing a type of abdominal colic seen in miners who uncovered arsenic. Roman Emperor Nero found these effects to be quite handy, using arsenic to kill off his brother Britannicus and ensure his own title.

Why was arsenic the go-to poison for everyone, from housewives to emperors? For starters, it’s virtually undetectable. Its most famous form, “white arsenic,” is odorless and, when concealed in food and drink, often tasteless. The symptoms are also helpfully similar to food poisoning. In times before refrigeration, when a king suddenly started having stomach cramps, vomiting his brains out, and filling the chamber pots with diarrhea, it wasn’t always obvious a killer was at hand. The Medici and Borgia families in Renaissance Europe used arsenic generously to kill off whomever got in their way. English essayist Max Beerbohm once said, “No Roman ever was able to say, ‘I dined last night with the Borgias.’” And even though Mary Frances Creighton earned nicknames like “the Long Island Borgia,” she was found not guilty of either suspicious death. In fact, she would go on to poison yet another person with arsenic years later.

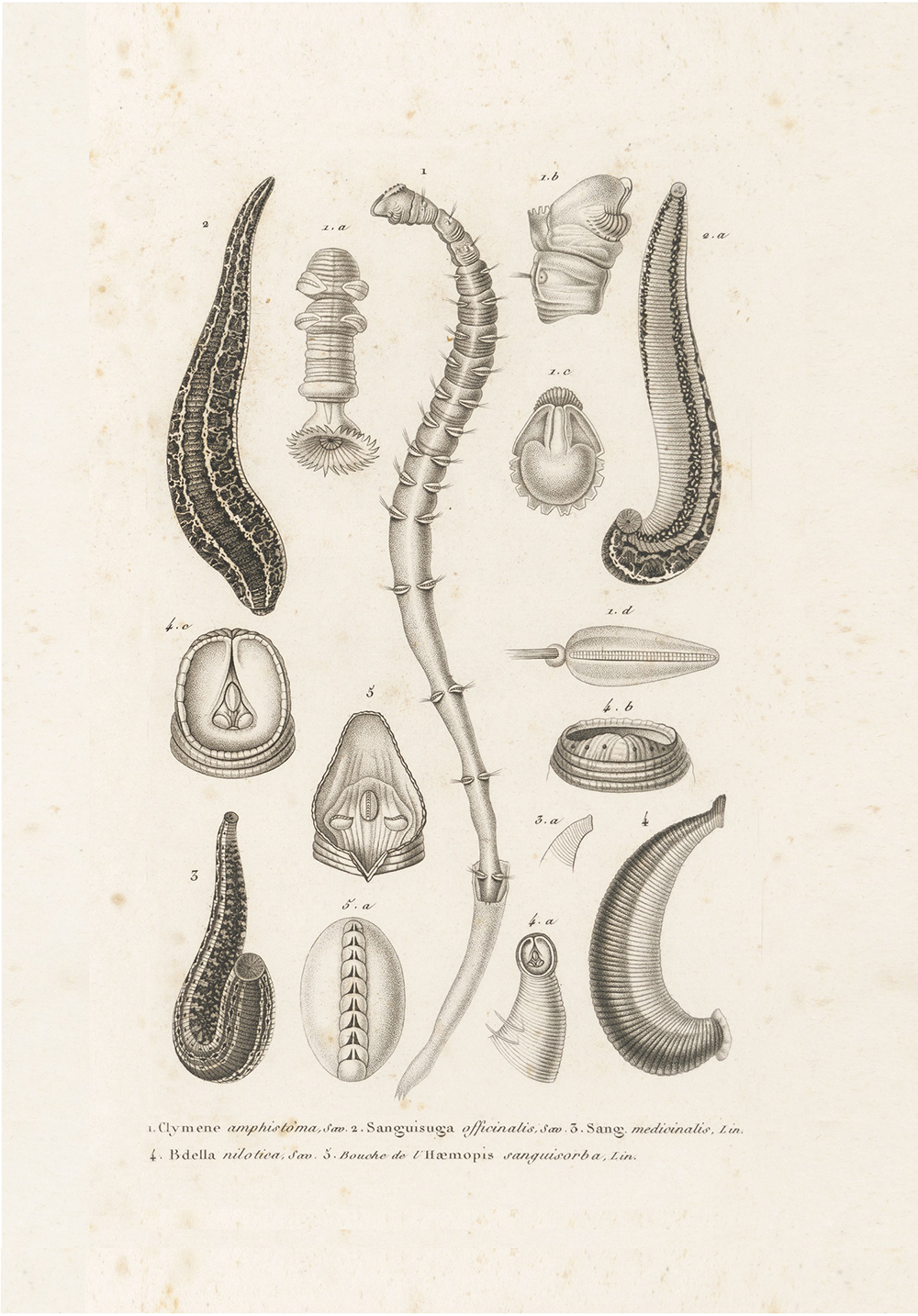

Making the Most of Your Leech

Leeches prefer to bite clean, freshly shaved skin. No stubble! “I have found the sharp points of the incised hairs so greatly to annoy them,” declared Mr. Wilkinson, a leech expert in 1804 London. Something to remember when wading in muddy ponds—prickly legs can be a good thing. But even with the smoothest of skin, the dainty beasts sometimes needed a little coaxing. The Lancet reported in 1848 that they bit more vigorously if dunked in a nice dark beer or some diluted wine. The area of skin could be bathed in milk, sugar water, or best, a little bit of fresh blood. Even a tiny knick from a knife tip could do the trick. This latter technique is still used today.

After fifteen minutes or so, the blood-filled leech usually fell off the patient, but occasionally the practitioner had to remove it. A sprinkling of table salt over the leech’s head helped because yanking it off might traumatize the skin. If the leech appeared to have fallen asleep from a food coma, a hard flick of the finger and a splash of water quickly revived it. Often after leeches were removed, further bleeding was coaxed from the bites by wrapping the area in warm linen to dilate the patient’s blood vessels. Others recommended perpetuating the ooze by submerging the patient in a warm bath.

In 1816 Dr. James Rawlins Johnson published his Treatise on the Medicinal Leech. Besides the aforementioned methods of leech use, he studied the leech itself with exacting care. He tested to see if they were cannibals (they were); he froze them with or without salt to see if they would die (snow plus salt was worse). He even had leech fights between burly horse leeches and medicinal leeches (the horse leeches won). He also tortured them with carbonic acid, mercury, gas pumps, and olive oil, and was surprised to find that the leech “is very tenacious of life.” (The authors stopped reading after they reached this choice sentence: “Hermaphroditic impregnation may occur in a single leech.” The visual is…never mind. Just don’t.)

As noted earlier, leeches were used inside the body, as well as outside. This, of course, begs the question: How to get the parasites out? Philip Crampton, an avid practitioner in 1822, had a solution: Thread the poor things. After applying these leeches directly to swollen tonsils, he noted that threading “causes them to bite with increased ardor, and, in fact, may be used to stimulate torpid leeches.”

They needn’t have worried: If a leech was swallowed, it would likely be digested by stomach acid. But not knowing this, medieval practitioners recommended gargling with goat urine, coaxing the leech out with a cautery iron, or making the patient thirsty as to “bait” it to crawl out for a refreshing drink of water. The ends did not justify the means by any extent because it didn’t work. Come to think of it, nothing justifies the drinking of goat urine.

There was also the matter of recycling. Leeches weren’t always tossed after a feeding. They could be reused up to fifty times if the animals were “encouraged” to disgorge: just dab a little salt on their mouths (which is really starting to sound like the leech equivalent of dabbing hydrochloric acid on a human). The leeches would then vomit like Ozzy Osbourne in his heyday. The cost savings were considerable. Other doctors would drop the engorged leeches into vinegar (a whole bath of acid!) and they’d perk up. Or so we imagine. In this manner, they could be used twice a week for up to three years.

The care and keeping of leeches was no small task. Mr. Wilkinson explained, “In short, so much patience, as well as dexterity, is required in the management of these capricious, or rather irritable animals.”

Excerpted from Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything by Lydia Kang MD and Nate Pedersen. Copyright © 2017 by Workman Publishing. Reprinted by permission.