Seated female, Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, c. second millennium bc. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Norbert Schimmel Trust, 1989.

Modern Central Asia has been shaped by a long history of interactions between the peoples of the Eurasian steppe and those of the agrarian societies (China, India, Iran, and Europe) that ring it. For environmental reasons, the steppe—the vast zone of grassland and desert that stretches from Hungary to Korea—cannot support a dense population.

Early human societies discovered that the best strategy for survival on the steppe was pastoral nomadism, in which animals (camels, sheep, cattle, and horses) provide the basis of livelihood. Nomadic groups laid claim to distinct pasturelands and followed fixed migration routes between winter and summer pastures. Over the centuries, steppe nomads interacted with neighboring sedentary societies through raiding, trading, and conquest. The domestication of the horse gave nomads mobility and a military advantage for a millennium and a half. During this period, they built a number of empires on the steppe that could dictate terms to their sedentary neighbors and occasionally conquer them outright.

Nomads were a constant presence on the frontiers of agrarian societies on Eurasia’s edges, which found it almost impossible to control the vast spaces of the steppe. The agrarian empires saw nomads as barbarians and a problem to be solved. The Great Wall of China, built to keep the northern barbarians out (and Chinese peasants in), is an apt indication of this attitude. The wall is equally apt as a metaphor for the relationship between the two worlds, because it never succeeded in separating them. Instead, they remained intertwined in a symbiotic and permeable relationship. The Great Wall sat in a borderland that was a perpetual arena of interaction. Many Chinese states were founded by “barbarians” from the north or northwest, even if their foreign origins were often covered up in historical narratives.

For a millennium and a half, the steppe was ascendant. Steppe nomads created a number of empires that extracted trading rights or tribute from their neighbors and sometimes conquered them. Such empires had several features in common. They appeared around a charismatic leader who claimed divine sanction of his sovereignty and who was therefore able to knit various tribes (political units imagined along genealogical lines) into viable confederations. The first major steppe empire was that of the Xiongnu, whom we know through the name that Chinese sources use for them. The empire lasted for well over two hundred years (third century bc–first century) and featured substantial urban settlements and a ramified administration.

In the western steppe, the Scythians and Sarmatians built empires about the same time. In the sixth and seventh centuries, a group of nomads called the Türk established another empire in what is now Mongolia. Its center was in the Orkhon valley, and it left behind runic inscriptions that are the oldest surviving texts in any Turkic language. In the eighth century, another confederation of Turkic tribes formed the Uighur empire. (Its name was to be revived in the twentieth century as the national name for the Turkic Muslim population of Xinjiang.) River valleys and oases, where sufficient amounts of water were available, gave rise to sedentary societies and states built on agriculture.

Transoxiana (the Land beyond the Oxus, which the Arabs called Mā warā’ al-Nahr or Maverannahr, the Land Beyond the River) and the oases of the Tarim basin were part of this agrarian world. The so-called Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex dates back to 2200–1700 bc and was a contemporary of civilizations in Egypt, Anatolia, and the Indus valley. In 539–330 bc the Achaemenid empire based in the Iranian plateau extended into Transoxiana, when the region was known as Sogdiana (Sughd). Alexander the Great defeated the Achaemenids, and Sogdiana became the easternmost part of his empire. He is supposed to have founded the city of Khujand as Alexandria Eschate (“Alexandria the Furthest”). Sogdiana was an independent Greco-Bactrian state in the third century bc before it fell to nomadic groups from the east, which eventually established the Kushan empire that expanded south into India. Zoroaster was born in Sogdiana, and Zoroastrianism had a long career in Central Asia. The Kushans adopted Buddhism, and it was through them that it traveled to China.

By the first century, these empires were linked by long-distance trade to China, India, and Iran. This trade is the basis of our contemporary cliché of the “Silk Road.” The term was coined in 1877 by the German geographer Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen, who used it to describe the routes along which Chinese silk was exported from the Han empire (206 bc–220) to Central Asia. Since then, however, the term has expanded to cover all trade that ostensibly linked “China” to “the West” for several centuries until it was displaced by maritime trade during Europe’s Age of Discovery. This trade is supposed to have underpinned Central Asia’s economy and made its civilization viable.

There is much that is problematic about this view. The most lucrative trade moved along a north-south axis, and not from east to west, nor was “the West” (that is, Europe) a significant partner in the east-west trade. Few goods and fewer people traveled from one end of the road to the other. But more significantly for our purposes, the concept of the Silk Road turns Central Asia into simply a pathway, rather than a place of interest in its own right. The Silk Road works better as a metaphor of connectivity across cultures than as a description of a concrete historical phenomenon. The nomads of the steppe spoke a variety of languages belonging to the Altaic family, which includes Mongolian, Tungusic, and a host of Turkic languages. Most of the sedentary population spoke various Indo-Iranian languages, which it shared with peoples in what are now Afghanistan and Iran. Transoxiana was always a frontier zone where the two linguistic families interacted the most intensely. It was the boundary between “Iran” and “Turan,” the land of the nomads. The “Iran” here is much more expansive than the present-day nation-state of that name.

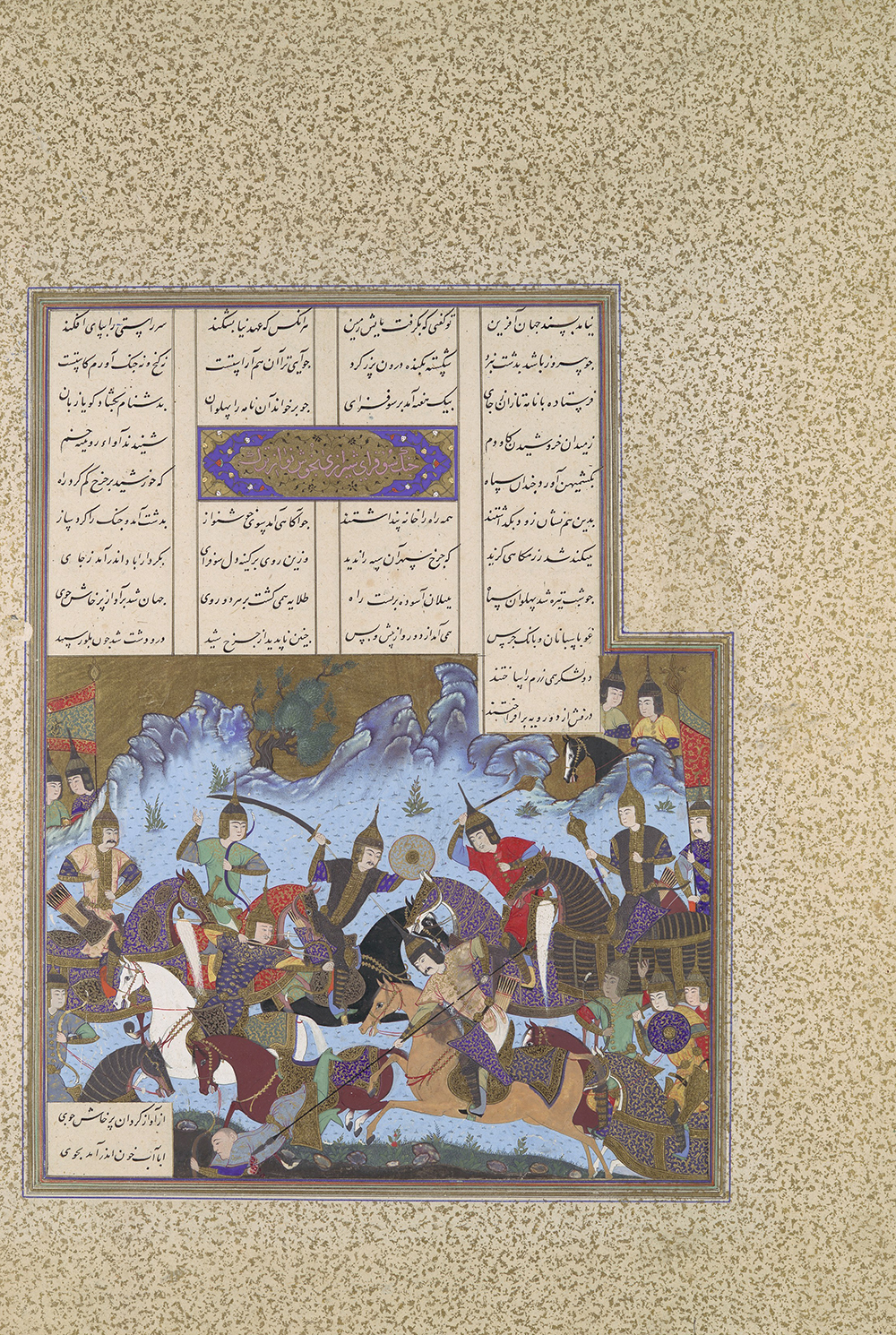

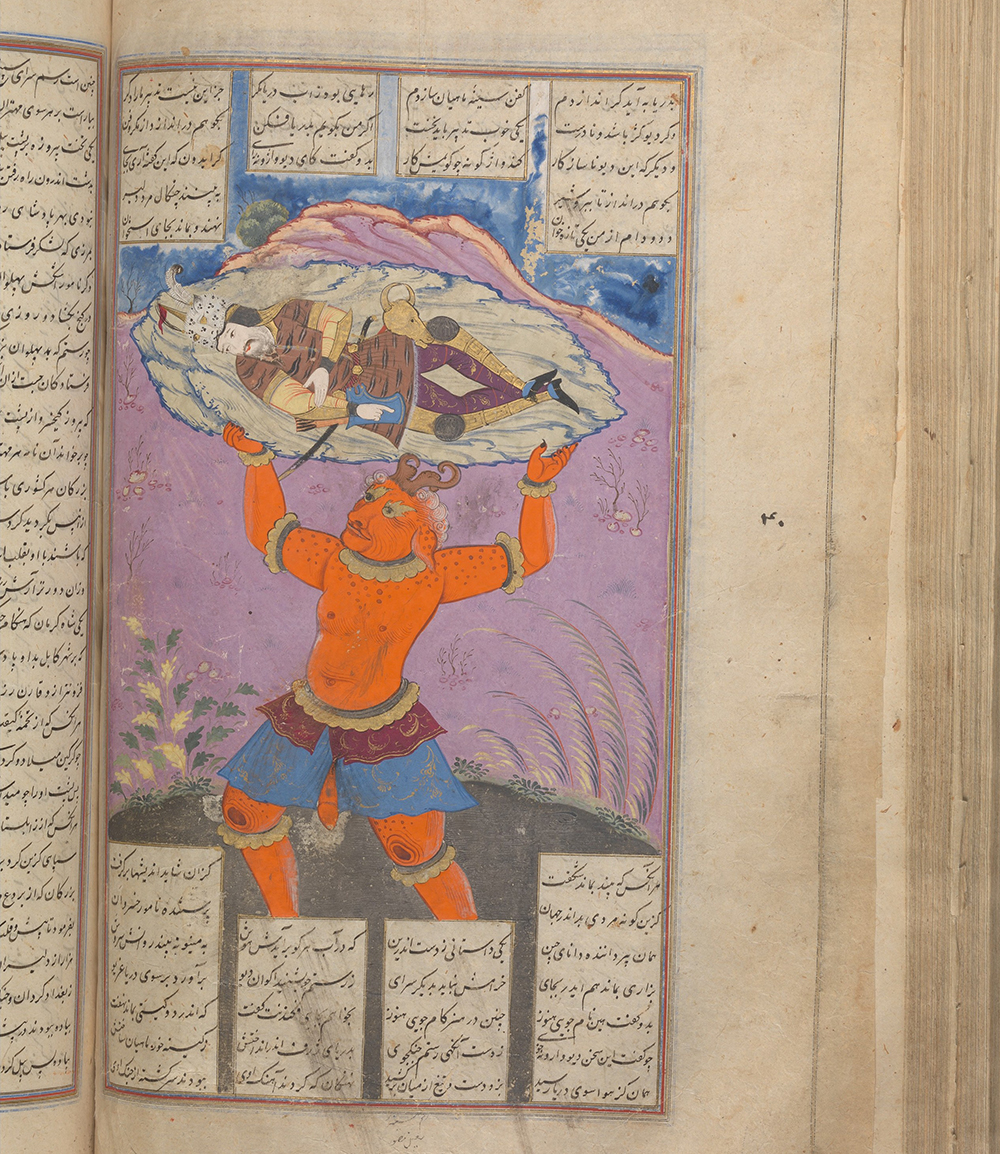

Much of the action in the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), the epic poem by Ferdowsi (c. 940–1020) commemorating the pre-Islamic Persian kings, is set not in present-day Iran but in Transoxiana. Central Asia was also heterogeneous in its religious heritage. The nomads were shamanist—that is, they believed in the ability of certain individuals to travel back and forth between the material and the spiritual worlds, either to enlist the support of various spiritual forces in pursuit of success in war or to ensure people’s health and well-being. Zoroastrianism and Buddhism were the prevalent religions among the sedentary population. In the eighth century, the Uighurs adopted Manichaeism, and Nestorian Christianity flourished in the oasis cities of the region in the first millennium. The religious heritage of Central Asia was truly diverse.

In the early eighth century, Transoxiana was conquered by Arab armies belonging to the Umayyad caliphate. Islam had emerged in the oasis cities of Arabia in the early seventh century, and its adherents, also pastoral nomads, embarked on a series of astonishing conquests that brought about the demise of the Sassanid empire in Iran, beat back the Byzantine empire into Anatolia, and created an Arab state that stretched from Spain to Transoxiana by the early eighth century.

The Arabs conquered Merv in 671 and Bukhara in 709 and annexed Transoxiana to their empire. The Arab conquests coincided with the greatest expansion of any Chinese dynasty until that point. The Tang controlled much of what is now Xinjiang. The two armies came face to face in 751 at the Battle of Talas (in what is now Kyrgyzstan), where Tang forces were routed and the dynasty’s westward expansion came to an end. In 750 the Umayyad dynasty was toppled by the Abbasids, a great deal of whose support came from insurgents in Iran and Transoxiana.

Conversion to Islam was a long-term process, however, and it took several generations for the majority of the sedentary, Persian-speaking population to become Muslim. Nonetheless, by the ninth century Transoxiana was solidly Muslim and had become an integral part of the Muslim world. Over the next two centuries, it produced a number of luminaries of the most fundamental importance in Islamic history. The sayings (hadith) of the Prophet Muhammad soon acquired a religious authority second only to that of the Quran, and their collection and categorization became a major preoccupation among scholars. Sunni Muslims hold six collections to be canonical. Two of the six compilers, Abu Isma‘il al-Bukhari (810–870) and Abu ‘Isa Muhammad al-Tirmidhi (825–892), were from Transoxiana, as were the influential jurists Abu Mansur Muhammad al-Maturidi (died c. 944) and Burhan al-Din Abu’l Hasan al-Marghinani (died 1197). The mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (780–850), who founded algebra (and whose name, through its Latin corruption, gives us the word algorithm); the astronomer Ibn Kathir al-Farghani (died 870); the great scientist Abu Nasr al-Muhammad al-Farabi (died c. 950), known as “the second teacher” (after Aristotle); the rationalist philosopher Abu ‘Ali Ibn Sina (known in the West as Avicenna, 980–1037); and the geographer Abu Rayhan al-Beruni (973–1050)—figures of absolutely central importance in the history of Islamic civilization in its so-called classical age—were all born in the region. They were part of broader networks of travel and learning that served to make the cities of Transoxiana part of the heartland of the Muslim world. It was in this age that Bukhara and Samarqand acquired their reputation in the wider Muslim world. To a thirteenth-century historian, Bukhara was “the cupola of Islam” in the Muslim East, “like unto Baghdad” (the capital of the Abbasid caliphate), and “its environs are adorned with the brightness of the light of doctors and jurists and its surroundings embellished with the rarest of high attainments.”

Given its vast expanse, the caliphate was always largely decentralized, and regional governors had a great deal of leeway. By the middle of the ninth century, they had begun to act as they pleased, paying only the most nominal allegiance to the caliphate. It was in this context that a certain Ismail Samani, a local governor in Transoxiana, established his own dynasty with its capital at Bukhara. Ismail received investiture from the Abbasid caliph, but he was to all intents and purposes a sovereign ruler. The Samanid dynasty that he founded presided over the rebirth of Persian as an Islamicate language. The great scholars we just encountered all wrote in Arabic (and therefore are often misidentified as Arabs), but neither they nor their compatriots ever used Arabic as a language of everyday intercourse. After the Arab conquests, Persian, the language of Transoxiana, had sunk to the level of a vernacular. The Samanids reversed this trend and raised it to a language of administration and culture. Their court patronized the creation of a new literary language, which we now call New Persian (even though today it is over a thousand years old). Written in Arabic script, with a large number of Arabic loanwords, it was Islamic in its sensibility. Its first great poet was Rudaki (858–941), but it was the Shahnameh, composed at the Samanid court, that laid the foundations of Persian as an Islamicate language of high culture.

Islam spread more slowly in the neighboring steppe. The first historical reports of large-scale conversion among the Turks date from 960, when 200,000 tents (households) are said to have embraced Islam. By the end of the tenth century, Muslim Turks had become quite common and begun to assume political power. Turkic nomads belonging to the Ghaznavid and Qarakhanid dynasties conquered Transoxiana and launched campaigns of conquest far and wide, going south into India and competing with other Muslim dynasties in eastern Iran and what is now Afghanistan.

Other Turkic groups entered military service in dynasties in the Middle East and became an integral part of the political landscape in that region. Over the ensuing centuries, Turks were to found a number of dynasties in the Muslim world. The Saljuqs fought the Byzantines and opened up Anatolia to Turkic settlement, where two centuries later the Ottomans established what became a mighty world empire. Yet the Islamization of the steppe was a long drawn out process that continued into the eighteenth century. Muslim societies interacted with non-Muslims along a long religious frontier that extended from Tibet to Zungharia and beyond.

Excerpted from Central Asia: A New History from the Imperial Conquests to the Present by Adeeb Khalid. Copyright © 2021 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.