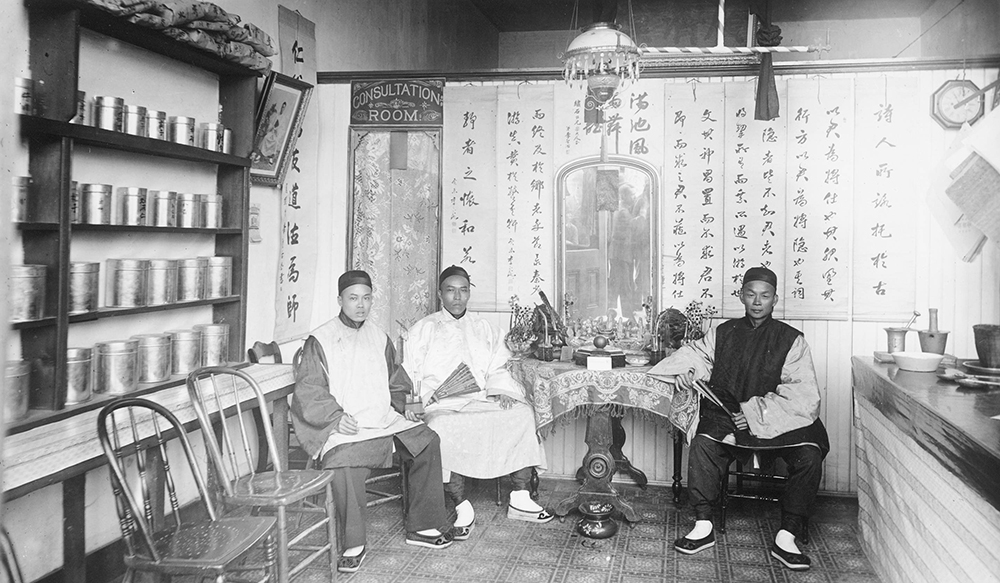

Dr. Henry Yee’s herb shop, 1935. Photograph by Frederick-Burkett Foto Service. Sacremento Public Library, Sacramento Room Photograph Collection.

In the fall of 1878 California healers engaged in a legal experiment. Two years earlier California had passed its first “Act to Regulate the Practice of Medicine in California,” known more colloquially as the “Anti-Quackery Act.” It stipulated that anyone practicing medicine in the state had to present a diploma from a “legally chartered medical school in good standing” for authentication by the Board of Examiners. To test the law’s constitutionality, E.J. Fraser, the president of the Homeopathic Medical Society, offered himself up for arrest. He was followed swiftly by a trio of irregular practitioners, including a man named Samuel H. Hall. As Hall stood for trial at San Francisco’s Criminal Court, he fingered another local physician practicing without a license: the celebrity Chinese herbalist Li Po Tai. Li was the first of many Chinese doctors arrested under the Anti-Quackery Act. In the next year, six other Chinese physicians practicing in San Francisco were charged under the same law. All were convicted, paid their fines, and went back to work as if nothing had happened.

California’s 1876 Anti-Quackery Act was at the forefront of a nationwide movement to regulate medical practitioners through public licensure. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, states organized one or more medical boards. They took responsibility for interviewing applicants, receiving fees, and issuing certificates to practice medicine and surgery in the state. Elite, formally trained physicians, with the support of national professional organizations like the American Medical Association, used their dominance on state boards to make their medical education the standard for licensing. Beginning in the 1890s state boards administered mandatory licensing exams that focused on recent medical science and pharmacology. Those exams contributed to the gradually consolidating meanings of medical science and helped distinguish regular from irregular medicine. Doctors practicing without a license faced the threat of fines and short prison sentences.

Regular physicians assisted law enforcement with the arrest and conviction of unlicensed doctors by studying, surveilling, and entrapping “quack” doctors in their midst. Chinese physicians were doubly vulnerable to such campaigns. Unlicensed and socially marginalized by nativist groups, they became prime targets, particularly in California and the West, where they were a more visible segment of the medical market. Although many Chinese physicians claimed to have degrees from Chinese medical colleges, their qualifications carried little weight among American professional societies. Arrests for practicing without a license became an expected part of doing business. With very few exceptions, Chinese herbalists did not acquire medical licenses nor did state boards create alternative examinations for Chinese doctors as they did for homeopaths, chiropractors, and osteopaths. Through the legal persecution of Chinese doctors, practitioners of scientific medicine asserted their power over the politics of public health and the American medical marketplace.

Regular physicians recognized Chinese doctors as competitors as early as 1870. A newspaper article on Chinese medicine noted, “In San Francisco, the regular physicians complain bitterly of the inroads made upon their incomes by the Chinese doctors, and they will make an effort to keep the healing business entirely in their own hands.” In the decades that followed, Chinese doctors often became part of an undifferentiated assault on irregular medicine. Dr. George Lee Eaton, a president of the San Francisco Board of Health, declared, “The psychological effect of these fakers, whether they are beauty doctors, so-called specialists, or Chinese herb doctors…cannot be estimated. One and all they are of the same stripe. They prey on the ignorant and the morbid.” There were a few instances in which legislators proposed bills that specifically targeted Chinese medicine, but more commonly Chinese doctors were arrested under state legislation or municipal ordinances restricting general “quackery.” Chinese physicians selling prescriptions through the mail also found themselves in violation of postal statutes passed by Congress in 1872. Although the original intention had been to prevent fraudulent financial schemes from circulating via the mail, the postmaster general began to apply the statutes to “quack medicines” around the turn of the twentieth century. The postal statutes worked in concert with the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, overseen by another federal agency, the Bureau of Chemistry. Because the postal statutes adopted a wider definition of fraud, the Postal Service could pursue cases outside the jurisdiction of the bureau.

Local medical societies sometimes threw their support behind regulatory schemes that promised to sweep up Chinese competitors. In 1891 the regular physicians of Butte, Montana, lobbied for a public health ordinance “for the suppression of quacks,” which required all practicing physicians to show a certificate from the state medical board. A newspaper article quoted various doctors supporting the ordinance including Dr. R.L. Gillespie, who claimed it would “stop the practicing of the Chinese doctors, whose only certificate is heredity,” and Dr. G.W. Monroe, who agreed that “it would shut out Chinese doctors and their tomfoolery. People should be protected against these Chinese doctors.” A judge in El Paso, Texas, appointed a board of medical examiners in 1887 and tasked them with “coppering the many Chinese doctors practicing there.” In Oregon, too, Multnomah County physicians organized a special committee to hire lawyers to prosecute complaints against “the quacks and charlatans now preying on the public” in Portland by practicing without a license, among them a man named Wing Lee, who was convicted and fined seventy-five dollars. Professional pharmacists also joined the push to restrict Chinese physicians. As early as 1893, a New Mexico newspaper reported, “The druggists of Las Vegas are persecuting a Chinese doctor under the provisions of the pharmacy act.” In 1907 the California State Board of Pharmacy identified the Chinese as the “most flagrant violators” of state medical laws and vowed to “pay particular attention” to them. The Los Angeles branch of the American Pharmaceutical Association devoted time at their meetings to discuss the popularity and dangers of Chinese drugs circulating in the city: “A great many of the drugs from Japan, China, and the Philippines are adulterated and mislabeled…It is an astounding fact, but nevertheless true, that Chinese pharmacists and physicians practice without legal restriction on the coast.” Such anti-Asian rhetoric called on a prevalent nativism. As historian Alan M. Kraut has argued, American nativists wielded scientific medicine as a “weapon” against non-Anglo-Saxon immigrants. In the case of anti-quackery campaigns, medical scientists deployed nativism to advance their own objective of marketplace dominance.

Regular physicians and pharmacists engaged in playacting when they helped gather evidence against Chinese doctors. Doing their part to suppress the illegal Chinese herb trade, members of the California State Pharmacy Board acted out a frontier vigilante fantasy in San Bernardino in 1914. Three inspectors, disguised “in rough attire,” swept into town to entrap unregistered druggists. The Los Angeles Times reported that the sting secured the arrest of seven sellers of morphine, a black woman in possession of opium, and three Chinese herbalists. Sting operations were not always so elaborately staged. In 1883 a member of the San Francisco Medical Society, F.A. Kelly, caught Joe Gong practicing medicine without a license. Pretending to be ill, Kelly went to Gong’s office on Waverly Place to ask for treatment. When Gong could not show his license, a San Francisco police offer was at the ready to arrest him.

Between 1914 and 1942, the California Board of Medical Examiners recorded 516 violations of the state’s Medical Practice Act by Chinese physicians. The board recorded 230 guilty verdicts, among which 161 were sentenced to pay a fine. In twenty-four cases, the judge offered a choice: either a fine or a short jail term. In all instances, the violator chose to pay the fine, which was typically one hundred dollars but occasionally as high as six hundred. Many physicians were brought up on charges multiple times over the course of their career. Between 1914 and 1942, forty-seven Chinese physicians were accused of committing three or more violations. One herbalist, Wah Quack, was arrested twice within twenty-four hours for violating anti-quackery laws in 1919.

At first, Chinese physicians attempted to comply with the new statutes to protect their businesses. In the 1880s state boards of health adopted a registration system for physicians, which typically required only a diploma from a medical college. Under this system, some Chinese doctors successfully secured their right to practice medicine, although often with the understanding that they would only treat members of their own race. States and municipalities initially accepted diplomas from Chinese medical colleges but dealt differently with the problem of translating them. When Dr. Lou See On of Buffalo, New York, presented a degree signed by the Chinese emperor in 1880, the county clerk agreed to register the physician, stipulating only that a copy of his diploma would need to remain on file, perhaps in the off-chance that a skilled interpreter would pass through town to verify its contents. In Sacramento, a clerk took on the unenviable task of copying a Chinese diploma, measuring a foot and a half square, by hand. He described the document as consisting of a “mass of Chinese hieroglyphics” as well as “fifty coarse outline sketches of the human figure, each being full of similar characters.” Other states required diplomas to be authenticated by Chinese officials in the United States. In 1887 the Louisiana Board of Health unanimously voted to approve the request of New Orleans doctor Kwai Ding Kwai to treat his fellow Chinese immigrants. As part of the registration process, Kwai had his diploma certified by the Chinese foreign minister in Washington and the Chinese consul in New York.

In these early decades of regulation, accommodations for Chinese doctors were not the product of their talents but rather a reflection of the fact that state boards of health and medical examiners were still insecure about their jurisdiction. They were therefore prone to adopting the most liberal interpretations of regulatory statutes. When the Louisiana Board of Health allowed Kwai Ding Kwai to practice medicine among his Chinese brethren in 1887, a member of the Committee on Registering Physicians justified the decision by asserting that the “board [of health] had no power to restrict any physician in his practice” so long as he had a “properly authenticated diploma.” In 1893, when Omaha doctor Chang Gee Wo appealed his conviction for practicing without a license and challenged the constitutionality of medical licensing, the Supreme Court of Nebraska denied his appeal but insisted that “the board…is not to use its power arbitrarily nor to refuse a certificate in a proper case, nor to attempt to build up any particular system.” Implicit in the language of the court’s decision was a common fear that one medical sect would monopolize licensing, as regular physicians endeavored to do.

American courts tended to agree that the state should be responsible for protecting the public from harm but favored regulation that gave different systems of education equal consideration. By the 1910s, however, federal courts had become more comfortable with differential licensing. In 1915 four San Francisco herbalists appealed their convictions for practicing without a license and filed writs of habeas corpus arguing that not only did licensing statutes unconstitutionally discriminate against certain medical sects but that they violated international treaties with China that guaranteed certain rights to Chinese immigrants. Lawyers for the complainants argued that “accredited practicing physicians from other countries…were permitted to practice without examination or license.” The federal court denied their appeal, insisting that the decision to issue licenses according to different standards was within the jurisdiction of California’s State Board of Medical Examiners.

When all else failed, Chinese physicians deployed extralegal strategies to circumvent discriminatory laws. They undoubtedly presented many fraudulent diplomas to licensing boards. Chinese doctors also bribed officials to “overlook” the law. In 1908 Los Angeles’ civil service commission charged Nick Harris, a sanitary inspector in the health department, with accepting bribes from the city’s Chinese doctors. Tom She Bin testified that he had given Harris gifts of a phonograph and a clock as well as money, and in exchange Harris had not prosecuted him for practicing medicine without a license. Witnesses for the defense countered that Harris arrested Chinese doctors with impartiality and that the phonograph in question was old and useless, but the commission dismissed him nonetheless. In 1919 Lowe Bin was caught in a sting operation after attempting to bribe Frank M. Smith, a special agent of the State Board of Medical Examiners, with seventy-five dollars in exchange for immunity from prosecution for three Chinese doctors practicing without a license in Oakland. Some Chinese doctors partnered with licensed practitioners, effectively using them as a legal cover for the illegal operations. Upon the death of Chinese doctor Pang Suey, it came to light that he had hired a registered physician named Robert Swift to work out of his office two days a week. Swift consulted with patients, diagnosed them, and then allowed Pang or his assistant to write and fill their prescriptions. Los Angeles–area physician S.P. Lee relied on his family members. One of his sons was a licensed chiropractor and the other a licensed osteopath. Both worked out of the family’s herb shops. The cover of licensed medical practitioners allowed Chinese doctors to keep up the pretense that they were simply selling herbs.

From Herbs and Roots: A History of Chinese Doctors in the American Medical Marketplace by Tamara Venit Shelton, now available from Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Tamara Venit Shelton. Reproduced by permission.