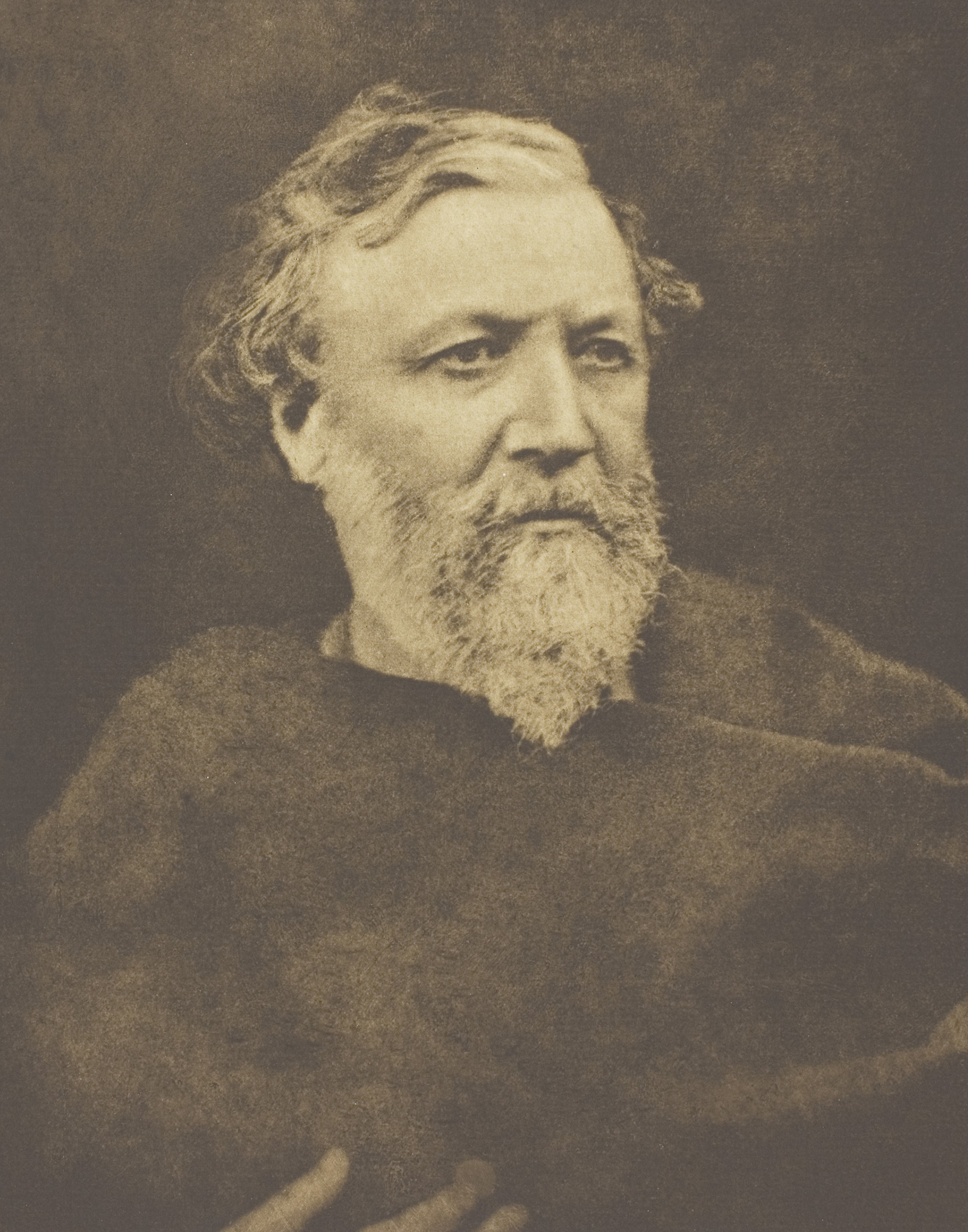

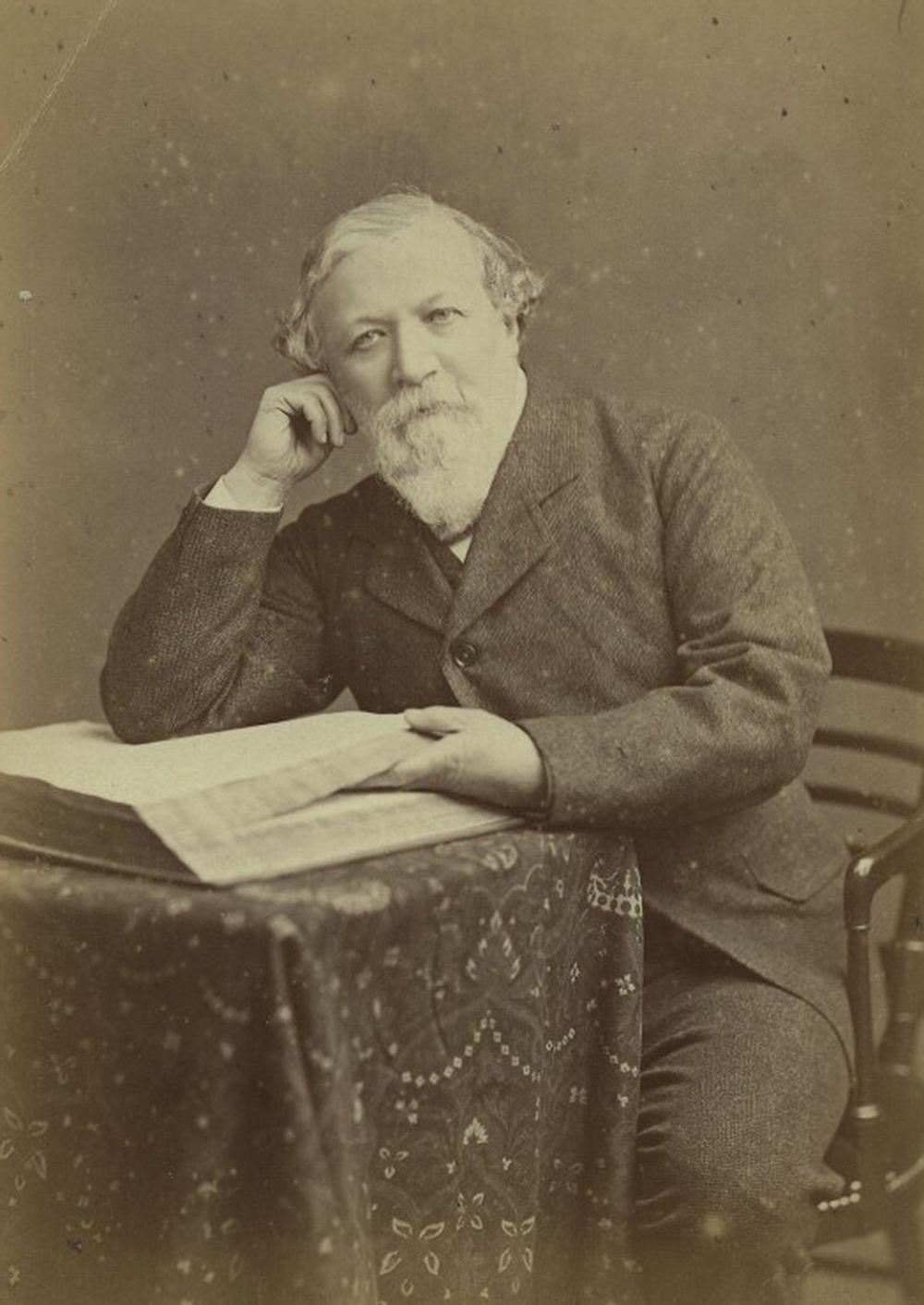

Robert Browning, by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1865. Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mrs. James Ward Thorne.

Hiram Corson was many things: a scholar of Anglo-Saxon literature, a translator of Roman satires, a theorist of education, but above all a diehard fan of the English poet Robert Browning. The Cornell professor dedicated the better part of his career to promoting, explicating, and declaiming Browning’s poems to an American audience, as well as founding a club exclusively dedicated to the poet in 1877. Toward the end of his life, Corson’s steadfast service was rewarded with one last opportunity to converse directly with the man he regarded as the greatest poetical mind since Shakespeare.

Over the course of several face-to-face exchanges, Browning assured the aging academic of their mutual intellectual understanding and thanked Corson effusively for the years spent propagating his poetry. None of this was particularly remarkable in itself—the two had met decades earlier and had even briefly traveled together in Italy. Far more noteworthy was the fact that at the time of these final conversations, Browning had been in his grave for twenty-two years.

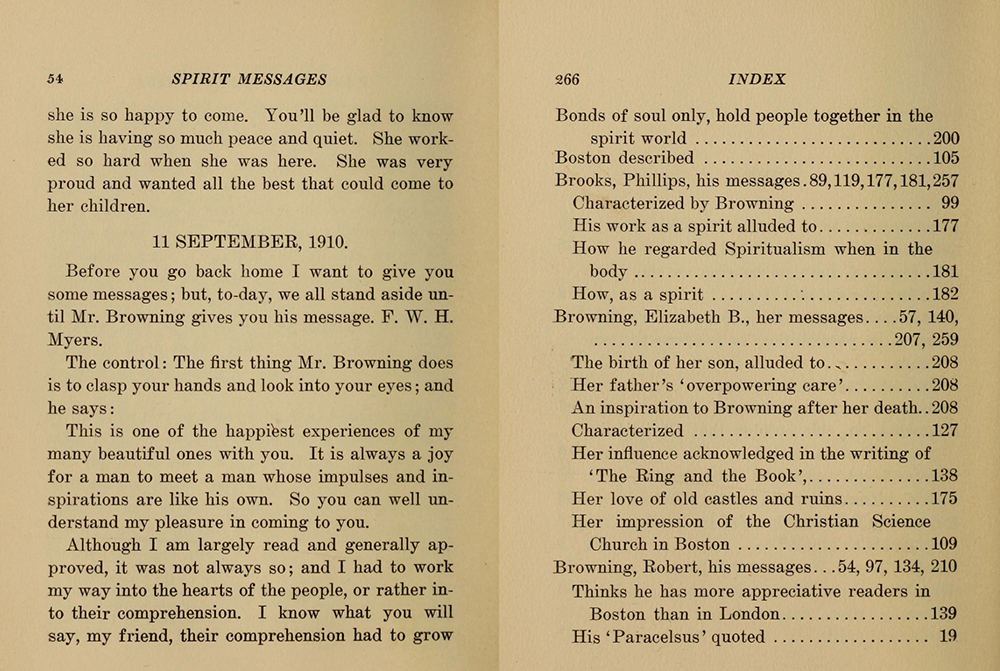

These spectral testimonies, recorded in Corson’s book Spirit Messages, were the product of a series of séances held at the home of a Boston medium named Minnie Meserve Soule in 1910. They were celebrity-studded affairs—deceased interlocutors from the sessions included Robert’s wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning; Nathaniel Hawthorne; Alfred Tennyson; William Gladstone; and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who obligingly brought along a “large band of Indian spirits” to protect the séance from otherworldly interference.

Browning, the book’s unquestionable star (despite having himself implicitly accused mediums of fraud in his poem “Mr. Sludge, ‘The Medium’ ”), speaks on a wide range of subjects, from the spirit world’s intermittently active interest in worldly affairs and the time he spends in the afterlife chatting with Tennyson about the metrical defects of contemporary poets to the enduring postmortem love between him and Elizabeth.1 Corson doesn’t ventriloquize the poet in any way contrary to Browning’s basic principles, and if the language doesn’t sound exactly like Browning, neither does it sound particularly unlike him. It is, in a sense, a formal mimicry of (or perhaps homage to) Browning’s own modus operandi: the adoption of others’ voices.

As a brazen bid for posterity by appealing to famous ghosts, Spirit Messages is both the product of an overly robust professorial ego and an artifact of the turn-of-the-century vogue for spiritualism. But Corson’s lingering obsession with Browning is also symptomatic of a particular, decades-long cultural fixation with the poet. In fact, the small club Corson established at Cornell in 1877 heralded the blossoming of hundreds of such Browning Societies across America and Browning’s native United Kingdom, a trend that continued well into the twentieth century. The fad was known as the “Browning craze,” “Browning fever,” or, as one periodical christened it, “Browningismus,” a prolonged flourishing of transatlantic devotion to the study and dissemination of all things Browning.

At first glance, the poet was an unlikely candidate to inspire an outpouring of public worship. After all, the most common complaint about his work was that it was frequently impenetrable, whether through density of allusion, breadth of diction, or intricacies of syntax. This forced his defenders into adopting frequently amusing critical defenses of Browning’s more abstruse passages. For instance, Corson argued that the seemingly cryptic lines “To be by him themselves made act, / Not watch Sordello acting each of them” from Sordello make perfect sense when one realizes that Browning simply refuses to abide by the syntactical laws that govern an uninflected language like English. “There are difficult passages in Browning which, if translated into Latin, would present no difficulty at all,” Corson insists, as though this were self-evident.2 It was precisely the demanding quality of Browning’s work that made it so suitable for endless, obsessive scrutiny and debate, however—the tantalizing promise that enough close attention would deliver some form of coherence. Scottish critic Andrew Lang provided a telling anecdote in the year of Browning’s death:

There is a story of two clever girls who set out to peruse Sordello, and corresponded with one another about their progress. “Somebody is dead in Sordello,” one of them wrote to her friend. “I don’t quite know who it is, but it must make things a little clearer in the long run!”

Further jeopardizing Browning’s prospects as a figure of popular devotion was the fact that his major work consisted mostly of dramatic monologues, spoken in the voice of figures as various as Pope Innocent XII, the Renaissance painter Andrea del Sarto, and Shakespeare’s Caliban, not to mention dozens of anonymous murderers, madmen, and eccentrics both historical and contemporary. Given this choice of genre, some critics argued, how could Browning have any unified sense of poetic self, any discrete personality or philosophical vision? What could anyone know about what Browning thought about anything, if all we have are his characters?

Again, however, Browning societies could transform this difficulty into a kind of useful provocation: through close study, perhaps Browning’s many masks could be penetrated, his true self made accessible. In this sense, the poet’s elusiveness, along with the obscurity of whatever spiritual or moral “message” he might have been offering, provided infinite interpretive possibilities, making possible an infinite number of Brownings. And so many Brownings promised a lot of spilled ink.

A significant portion of that ink would issue from the most prominent Browning society of them all, the London Browning Society. Its founders were Frederick James Furnivall and Emily Hickey, two Victorian curios who may as well have been Browning monologuists themselves. Hickey was a precocious poet (she published her first long poem at twenty and would ultimately produce twelve volumes of verse) who supported herself by working as a governess, secretary, and journalist. She would eventually convert to Catholicism and spend the rest of her days in monastic seclusion, writing for an explicitly Catholic audience (for which the pope awarded her the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice decoration), but she remained a devoted Browningite until death.

Furnivall was the more outspoken and visible of the two. “No man in England has done so much work for nothing, so perseveringly, as I’ve done,” he once declared. If this was hyperbole, it was relatively modest in its exaggeration. An ever-zealous philologist, educator, and reformer—and friend of Thomas Carlyle, Charles Kingsley, Elizabeth Gaskell, John Ruskin, and seemingly every other spirit of the age—Furnivall helped establish the Christian Socialist Working Men’s College, cofounded the Oxford English Dictionary, and instituted England’s first all-women’s rowing club in 1896 (years earlier, he had also invented a new, more efficient model of sculling boat). He agitated on behalf of cooperative stores, argued in favor of women’s suffrage, and once allegedly sold his library to benefit a group of striking woodcutters. A close friend dubbed him the “Grand Old Optimist.”

Above all, Furnivall was a compulsive creator of literary societies. The Early English Text Society, the Ballad Society, the Chaucer Society, the New Shakespeare Society, the Wycliffe Society, and the Shelley Society all could claim Furnivall as their father. (“Of making societies there is no end, and there never will be as long as Dr. F.J. Furnivall lives,” quipped one contemporary magazine.) But the Browning Society was a unique venture insofar as it was dedicated not only to a living poet, but to one both its founders personally knew. Days before announcing the society’s establishment, Furnivall and Hickey visited Browning, informing him of their plans. Accounts of Browning’s response vary, but it seems fair to say that he was neither beside himself with enthusiasm nor entirely opposed to the idea. (This was despite the fact that he had recently concluded an unpleasant tenure as president of Furnivall’s New Shakespeare Society, marked by a ferocious dispute between Furnivall and the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne over whether and how the plays should be dated). In the end, however reluctantly, Browning gave the society his blessings.

A few months later, on October 28, 1881, in the Botany Theatre at University College, about three hundred Londoners convened for the London Browning Society’s inaugural meeting. As its prospectus noted, the society’s goals were ambitious: beyond encouraging the “study and discussion” of Browning’s poems, it would foster “the publication of Papers on them, and extracts from works illustrating them…the formation of Browning Reading-Clubs, the acting of Browning’s dramas by amateur companies, the writing of a Browning Primer, the compilation of a Browning Concordance or Lexicon, and generally the extension of the study and influence of the poet.”

The society’s monthly gatherings were scrupulously documented. Papers and talks given were preserved, abstracts of meetings were drawn up, byzantine organizational charts were carefully maintained. Members created wildly complex critical bibliographies, obsessively precise records of publication, and comprehensive lists of rhyme changes between various editions of some of the longer poems, all the while squabbling over interpretive minutiae. Furnivall was, in effect, bringing the same philological tools to bear on Browning’s corpus that he had on Middle English poetry through the Early English Text Society, the same obsession with textual authority and scholarly meticulousness. Why wouldn’t the preeminent poet of the age (in Furnivall’s estimation) be worthy of the same study as Chaucer? As Shakespeare?

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Corson’s endless advocacy work and famously theatrical recitations had spawned Browning societies in nearby Rochester and Syracuse. Browning enjoyed a kind of countercultural reputation, his experimentation a welcome reprieve from the fusty Fireside Poets that had dominated nineteenth-century literary culture. Soon other groups were cropping up in the major cities: Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Chicago. By some counts, there were some nine hundred American Browning clubs throughout the United States at the craze’s pinnacle. Their internal affairs were the subject of national press attention. An 1894 New York Times article describes in great detail one society’s censure of a member for acting with “untimely levity” during a reading of one of Browning’s plays. The headline: boston browning society offended.

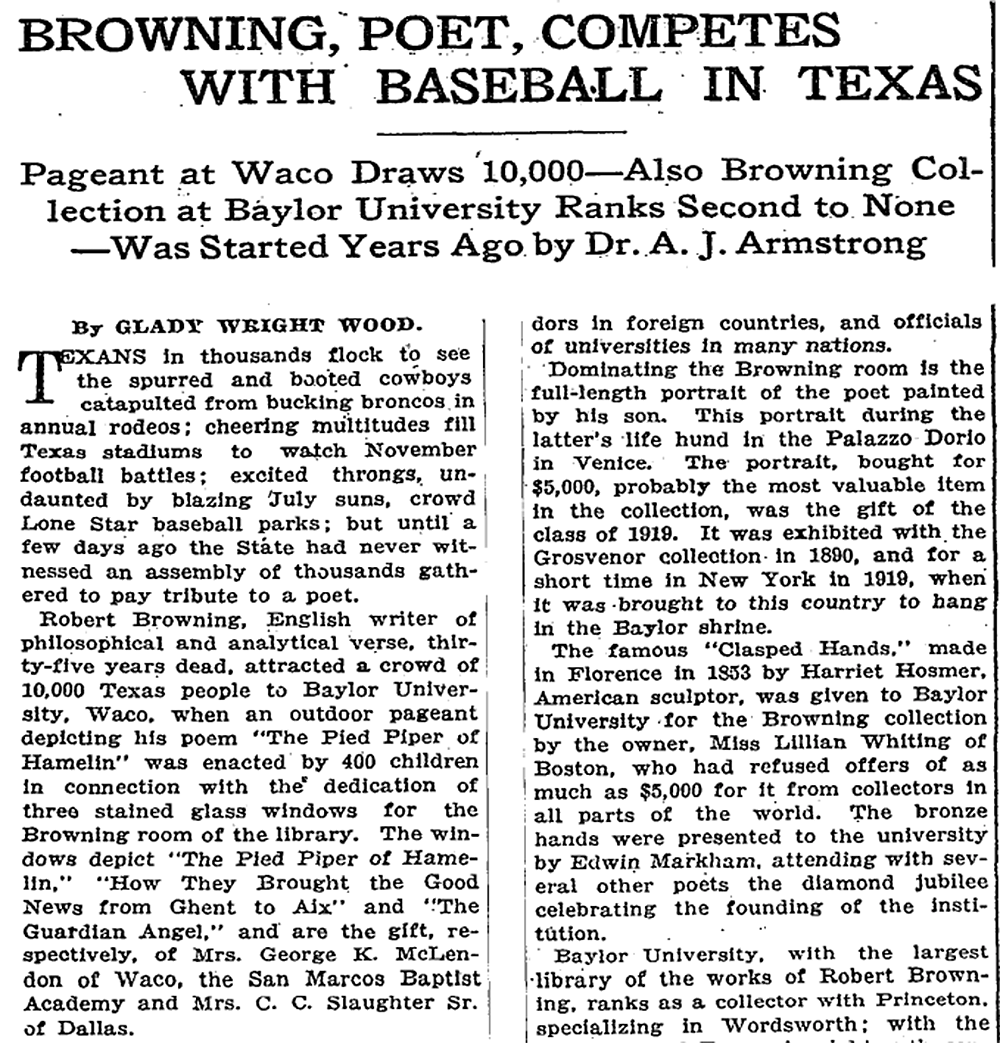

Browning himself recognized Americans’ particular affinity for him, purportedly claiming that Chicagoans were his most ardent and sophisticated readers. It’s not improbable—the Chicago and Alton Railroad reprinted Browning’s poetry in its official guide during the 1870s, so that passengers might read it on their journey. The world’s largest Browning archive is located in the unlikely city of Waco, Texas, the product of one early twentieth-century Baylor professor’s career-long infatuation. Dr. A.J. Armstrong fell in love with Browning as a young academic—at one point he was studying the poet’s works for up to thirteen hours a day—and began to amass a large collection of Browningiana that ultimately grew into the Armstrong Browning Library. Armstrong’s enthusiasm seems to have been infectious: a 1924 children’s performance of Browning’s Pied Piper of Hamelin at Baylor supposedly drew an audience of ten thousand (the New York Times again: browning, poet, competes with baseball in texas).

Back in England, some members of the London Browning Society demonstrated their affinity for the poet through their own literary production. One Society member, the poet and critic Arthur Symons, published “A Fancy of Ferishtah,” a poem in which Browning is cast as an ancient Persian sage (“Thrice-honored Master, Light of Nishapur / Star to whose shining Persis gazeth up!”) whose poetry inspires a Symons-esque youth eager to “make some day some / Small, small, however small name for himself.” Another passionately committed member, the physician Edward Berdoe, expressed his appreciation by penning a bizarre novel called St. Bernard’s: The Romance of a Medical Student under the pen name Aesculapius Scalpel, in which a morally errant young doctor returns to the path of righteousness through careful study of Browning’s Paracelsus, a poem about the titular sixteenth-century Swiss alchemist.

The fact that so much Browning adulation was carried on without a whiff of self-consciousness or humor made the societies inevitable targets of satire. Arthur Conan Doyle’s justly forgotten 1899 novel A Duet, with an Occasional Chorus, for instance, crudely dismisses Browning societies as the domain of parochial suburban housewives. The novel describes the first meeting of one such society, consisting of just three women, whose attempts at engaging with Browning’s poetry are continually derailed by ancillary discussions of ball gowns, hairstyles, and the seasonality of oysters. By the time they get around to tackling “Caliban upon Setebos,” they are totally bewildered. “Dear me, I had no idea Browning was like this,” notes one member. “What nonsense it is.” Another remains confident that there is something in Browning, even if it escapes their analysis: “It is very easy to call everything which we do not understand ‘nonsense’…I have no doubt that Browning had a profound meaning in this.” If so, they don’t discover it. The meeting concludes after a mere hour, and the members all resolve to read Tennyson instead.

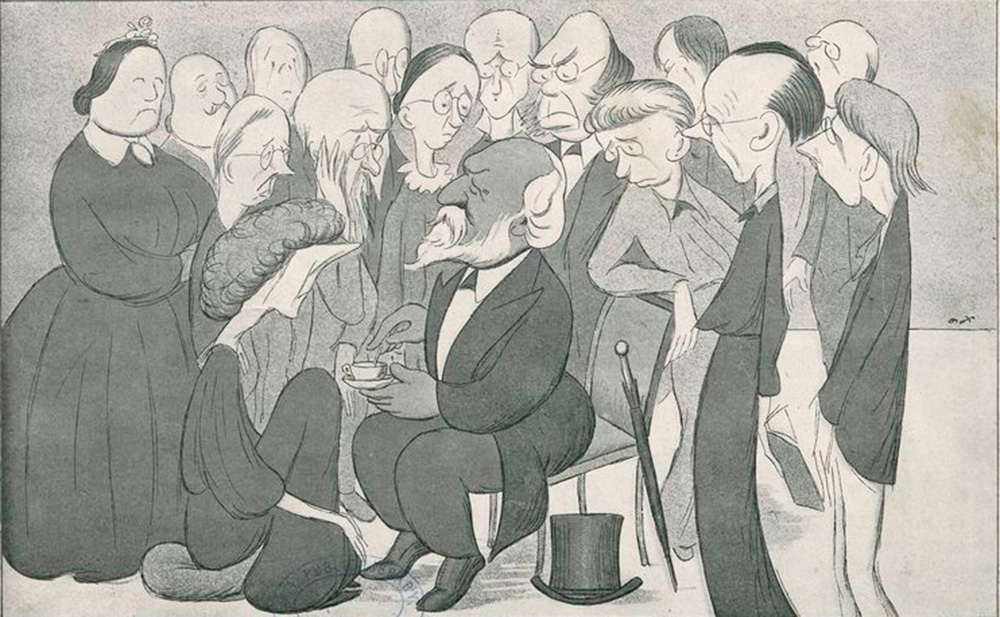

In the popular press, satirical treatments of Browning’s disciples were ubiquitous in both the United States and England; most, like Doyle’s, portrayed society members as the ignorant thralls of literary modishness. A particularly well-known Max Beerbohm drawing in Punch tweaks the formula slightly, depicting Browningites as fawning, austere sycophants. Illustrated in black and white, Browning’s admirers cluster around the master—himself rendered in color—looking both unmistakably dour and wholly rapt. One elderly woman sits directly in front of the poet, looking as though she’s either about to wash his feet or administer some shoe polish. The archetypal Society member, it seems, was either an unsophisticated suburbanite or a pitiable flatterer.

There is some kernel of truth to these caricatures: society members were often middle-class women who found a welcome opportunity in Browning societies for public “literary” discourse. The clubs also resonated with the religious, particularly those inclined toward evangelicalism. The inaugural meeting of the London society, as one speaker noted, included a “great proportion of clergymen and ladies.” Yet Browning societies on both continents were more diverse than the satirists would suggest, encompassing a wide range of perspective and experience—amateurs and experts, young and old, men and women. It was nevertheless difficult to shake a reputation as the realm of doting dilettantes. (George Bernard Shaw, while a card-carrying member of the London society, later claimed he joined only to make fun of the “pious ladies.”)

The London Browning Society, bankrupt and torn apart by internal debates between Christian and agnostic factions, disbanded in 1892. Punch, unsurprisingly, found the occasion a cause for celebration. “Hark! ’tis the knell of the Browning Society,” it declared. “Windbags are busting all round us today.” Other societies would persevere for decades, but by the 1920s and ’30s, it’s safe to say that the network of Browning societies across the UK and America had largely collapsed. Perhaps Browning had been outmodernized by the modernists, perhaps the clubs founded in his name had fallen victim to the professionalization of literary study, or perhaps they had simply gone the way of all fads.

Yet certain societies endured and still do, though in far more modest iterations. In his 1969 history of the London Browning Society, the scholar William S. Peterson (to whose work I’m much indebted) noted that, “Browning clubs today…carry a slightly musty odor about them, as if they do not quite belong to the twentieth century.” Needless to say, the same is true fifty years later, though clubs still soldier on. The contemporary Browning Society based in London, despite having to cease publication of the Journal of Browning Studies and awarding of its Poetry Prize, still promotes events in honor of both Robert and Elizabeth: a “flower festival” at Pembury Parish Church, where the Brownings’ son was married; a “Browning Sunday” at St. Marylebone Parish Church to commemorate the anniversary of the Brownings’ marriage; an annual wreath-laying ceremony in Poets’ Corner. Musty, yes, but undeniably charming in its commitment to honoring the legacy of not only Robert Browning but also the assortment of oddballs who conspired to enshrine his status as an actual cult favorite in the first place.

1 In what is perhaps the most outrageous moment in Spirit Messages, Corson has Robert misquote Elizabeth’s poem Aurora Leigh, then corrects him in a footnote. ↩

2 Sordello in particular was renowned for its inscrutability. One story has it that the writer Douglas Jerrold, while recuperating from an illness, found himself so unable to make sense out of Sordello that he was convinced the disease had cost him his mind. ↩