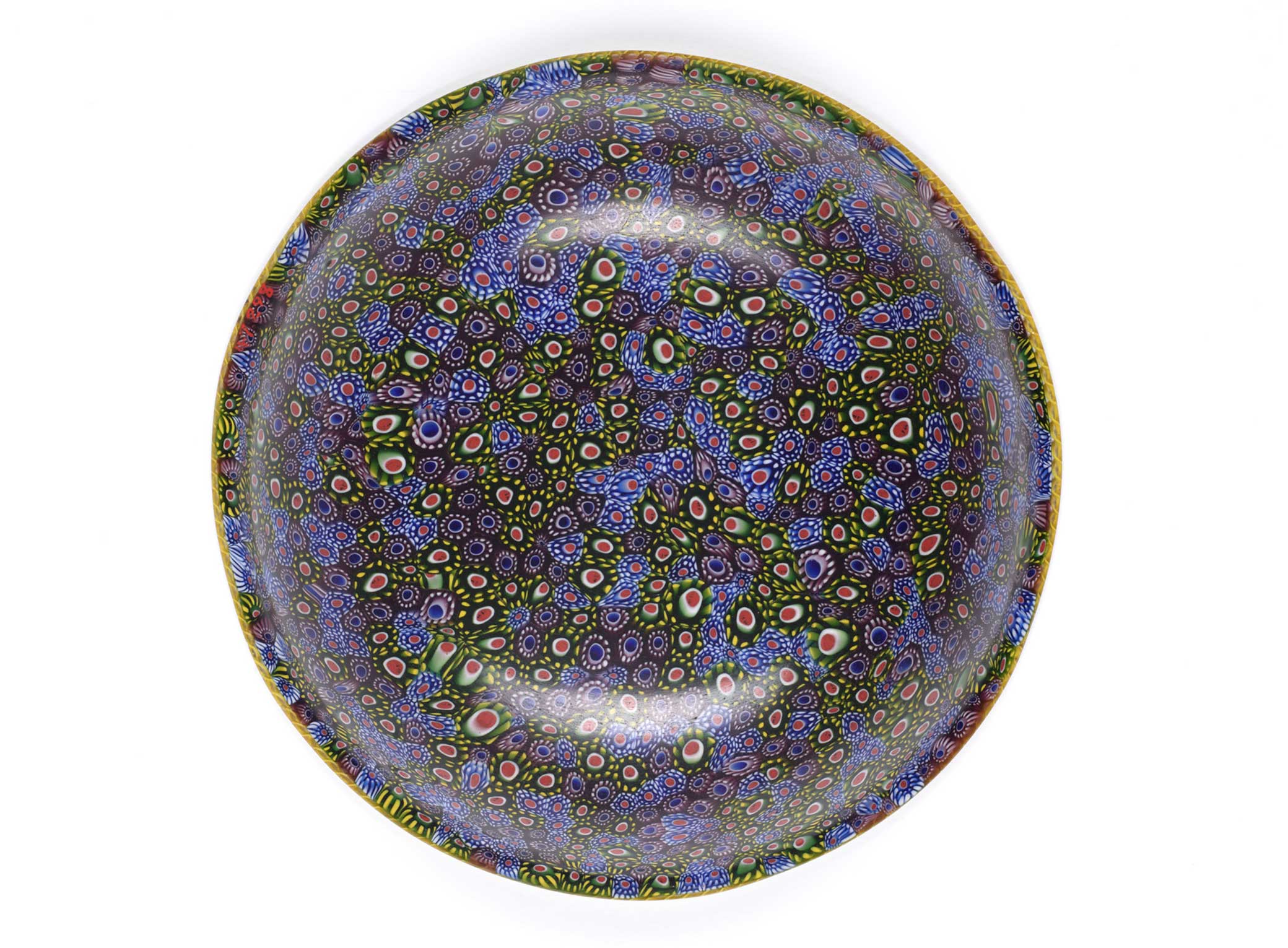

Mosaic bowl, by Salviati & Co., circa late nineteenth century. The Walters Art Museum, acquired by Henry Walters.

For the rest of the year, Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the subject of history and the pleasures, pain, and knowledge that can be found from studying it. For more than fifty issues, contributors from antiquity to the present day have participated in millennia-spanning conversations on themes including friendship, happiness, death, and the future. But what did they make of the idea of studying the past in the first place? Check back every Thursday from now until the end of the year to read the latest.

“In your studies, you have yet to begin a system,” Vice President John Adams wrote to his twentysomething son John Quincy Adams in 1790. “From all I have seen and read, I have formed an opinion of my own, and I now give it you as my solemn advice, to make yourself master of the Roman learning.” After consuming a rasher of it, “you will say that you have learned more wisdom from it than from five hundred volumes of the trash that is commonly read.” In particular, he advised, “Polybius and Plutarch and Sallust as sources of wisdom as well as Roman history must not be forgotten, nor Dionysius of Halicarnassus.”

Polybius’ Histories were written during the second century bc and covered roughly the same time period. When the Greek historian was sent to Rome as a hostage after the defeat of Perseus, the last king of Macedonia, his friendship with the general Scipio Africanus the Younger made it possible to stay while other detainees were shipped elsewhere—and also allowed him the chance to occasionally serve as his own eyewitness to Roman history, which came in handy when he sat down to write it.

“He came to the writing of history,” the classical scholar and historian F.W. Walbank wrote in 1972,

not as a scholar, but rather in the spirit of the Roman senatorial writers, who saw this activity as a complement to their public careers, and also as a man who believed fervently and often repeated that the study of history was the best way of acquiring experience in war and politics. That, rather than mere bookishness, is why he was widely read in the Greek historians, especially those of the fourth and third centuries.

Of the forty books Polybius wrote for the Histories, only five made it to the present day in their entirety. Adams treasured the Histories for the discussion of the Roman constitution and the separation of powers. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, close behind Polybius in Adams’ syllabus, found his predecessor a bore, deeming him among those who “have left behind them compositions which no one endures to read to the end.”

Polybius also left behind influential feelings about how to write history. He did not consider himself a storyteller, as he makes clear in Book II.

The object of tragedy is not the same as that of history but quite the opposite. The tragic poet should thrill and charm his audience for the moment by the verisimilitude of the words he puts into his characters’ mouths, but it is the task of the historian to instruct and convince for all time serious students by the truth of the facts and the speeches he narrates, since in the one case it is the probable that takes precedence, even if it be untrue, in the other it is the truth, the purpose being to confer benefit on learners.

Polybius begins Book I with a longer discussion of history, or at least his version of it.

Had previous chroniclers neglected to speak in praise of history in general, it might perhaps have been necessary for me to recommend everyone choose for study and welcome such treatises as the present, since men have no more ready corrective of conduct than knowledge of the past. But all historians, one may say without exception—and in no halfhearted manner, but making this the beginning and end of their labor—have impressed on us that the soundest education and training for a life of active politics is the study of history, and that the surest and indeed the only method of learning how to bear bravely the vicissitudes of fortune is to recall the calamities of others. Evidently therefore no one, and least of all myself, would think it his duty at this day to repeat what has been so well and so often said. For the very element of unexpectedness in the events I have chosen as my theme will be sufficient to challenge and incite everyone, young and old alike, to peruse my systematic history. For who is so worthless or indolent as not to wish to know by what means and under what system of polity the Romans in less than fifty-three years have succeeded in subjecting nearly the whole inhabited world to their sole government—a thing unique in history? Or who again is there so passionately devoted to other spectacles or studies as to regard anything as of greater moment than the acquisition of this knowledge?

How striking and grand is the spectacle presented by the period with which I purpose to deal will be most clearly apparent if we set beside and compare with the Roman dominion the most famous empires of the past, those which have formed the chief theme of historians. Those worthy of being thus set beside it and compared are these. The Persians for a certain period possessed a great rule and dominion, but so often as they ventured to overstep the boundaries of Asia they imperiled not only the security of this empire but their own existence. The Lacedaemonians, after having for many years disputed the hegemony of Greece, at length attained it but to hold it uncontested for scarce twelve years. The Macedonian rule in Europe extended but from the Adriatic region to the Danube, which would appear a quite insignificant portion of the continent. Subsequently, by overthrowing the Persian empire they became supreme in Asia also. But though their empire was now regarded as the greatest geographically and politically that had ever existed, they left the larger part of the uninhabited world as yet outside it. For they never even made a single attempt to dispute possession of Sicily, Sardinia, or Libya, and the most warlike nations of Western Europe were, to speak the simple truth, unknown to them. But the Romans have subjected to their rule not portions but nearly the whole of the world and possess an empire that is not only immeasurably greater than any which preceded it but need not fear rivalry in the future. In the course of this work it will become more clearly intelligible by what steps this power was acquired, and it will also be seen how many and how great the advantages that accrue to the student from the systematic treatment of history.

The date from which I propose to begin my history is the 140th Olympiad, and the events are the following: in Greece the so-called Social War, the first waged against the Aetolians by the Achaeans in league with and under the leadership of Philip V of Macedonia, the son of Demetrius II and father of Perseus; in Asia the war for Coele Syria between Antiochus and Ptolemy IV Philopator; in Italy, Libya, and the adjacent regions, the war between Rome and Carthage, usually known as the Hannibalic War [or the Second Punic War].

These events immediately succeed those related at the end of the work of Aratus of Sicyon. Previously the doings of the world had been, so to say, dispersed, as they were held together by no unity of initiative, results, or locality; but ever since this date history has been an organic whole, and the affairs of Italy and Libya have been interlinked with those of Greece and Asia, all leading up to one end. And this is my reason for beginning their systematic history from that date. For it was owing to their defeat of the Carthaginians in the Hannibalic War that the Romans, feeling that the chief and most essential step in their scheme of universal aggression had now been taken, were first emboldened to reach out their hands to grasp the rest and to cross with an army to Greece and the continent of Asia.

Now were we Greeks well acquainted with the two states that disputed the empire of the world, it would not perhaps have been necessary for me to deal at all with their previous history or to narrate what purpose guided them, and on what sources of strength they relied, in entering upon such a vast undertaking. But as neither the former power nor the earlier history of Rome and Carthage is familiar to most of us Greeks, I thought it necessary to prefix this book and the next to the actual history, in order that no one after becoming engrossed in the narrative proper may find himself at a loss, and ask by what counsel and trusting to what power and resources the Romans embarked on that enterprise which has made them lords over land and sea in our part of the world; but that from these books and the preliminary sketch in them, it may be clear to readers that they had quite adequate grounds for conceiving the ambition of a world empire and adequate means for achieving their purpose.

For what gives my work its peculiar quality, and what is most remarkable in the present age, is this. Fortune has guided almost all the affairs of the world in one direction and has forced them to incline toward one and the same end; a historian should likewise bring before his readers under one synoptical view the operations by which she has accomplished her general purpose. Indeed, it was this chiefly that invited and encouraged me to undertake my task, and secondarily the fact that none of my contemporaries have undertaken to write a general history, in which case I should have been much less eager to take this in hand. As it is, I observe that while several modern writers deal with particular wars and certain matters connected with them, no one, as far as I am aware, has even attempted to inquire critically when and whence the general and comprehensive scheme of events originated and how it led up to the end. I therefore thought it quite necessary not to leave unnoticed or allow to pass into oblivion this the finest and most beneficent of the performances of fortune. For though she is ever producing something new and ever playing a part in the lives of men, she has not in a single instance ever accomplished such a work, ever achieved such a triumph, as in our own times. We can no more hope to perceive this from histories dealing with particular events than to get at once a notion of the form of the whole world, its disposition and order, by visiting, each in turn, the most famous cities or indeed by looking at separate plans of each: a result by no means likely. He who believes that by studying isolated histories he can acquire a fairly just view of history as a whole is, as it seems to me, much in the case of one who, after having looked at the dissevered limbs of an animal once alive and beautiful, fancies he had been as good as an eyewitness of the creature itself in all its action and grace. For could anyone put the creature together on the spot, restoring its form and the comeliness of life, and then show it to the same man, I think he would quickly avow that he was formerly very far away from the truth and more like one in a dream. For we can get some idea of a whole from a part but never knowledge or exact opinion. Special histories therefore contribute very little to the knowledge of the whole and conviction of its truth. It is only indeed by study of the interconnection of all the particulars, their resemblances and differences, that we are enabled at least to make a general survey, and thus derive both benefit and pleasure from history.

Read the other entries in this series: Michel de Montaigne, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hardy, Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto, Voltaire, Charles Lamb, al-Biruni, Ibn Khaldun, Germaine de Staël, and Agnes Strickland and Elizabeth Strickland.