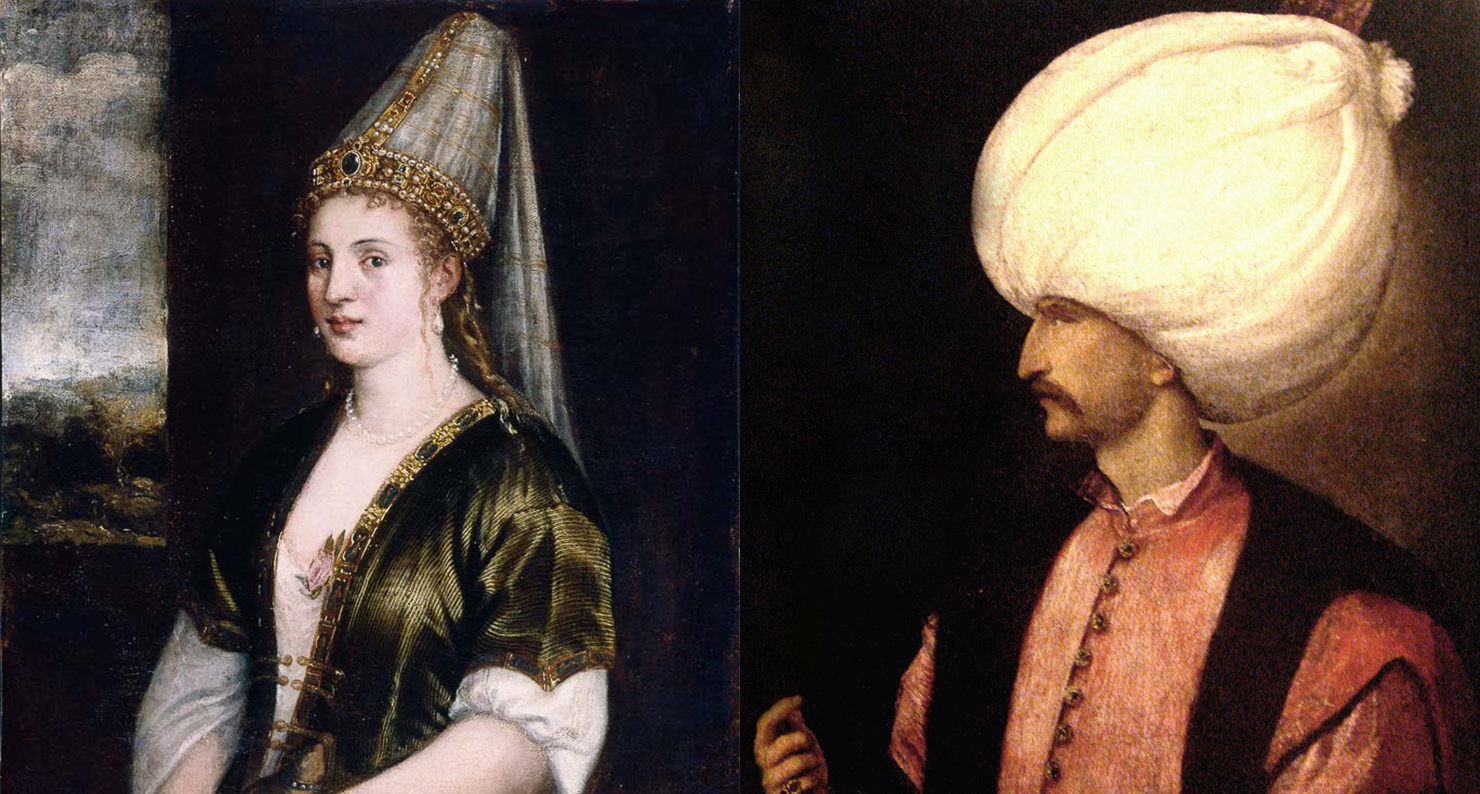

(L) La Sultana Rossa, by Titian, c. 1550. Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota. (R) Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, by Titian, c. 1530–50. Kunsthistorisches Museum.

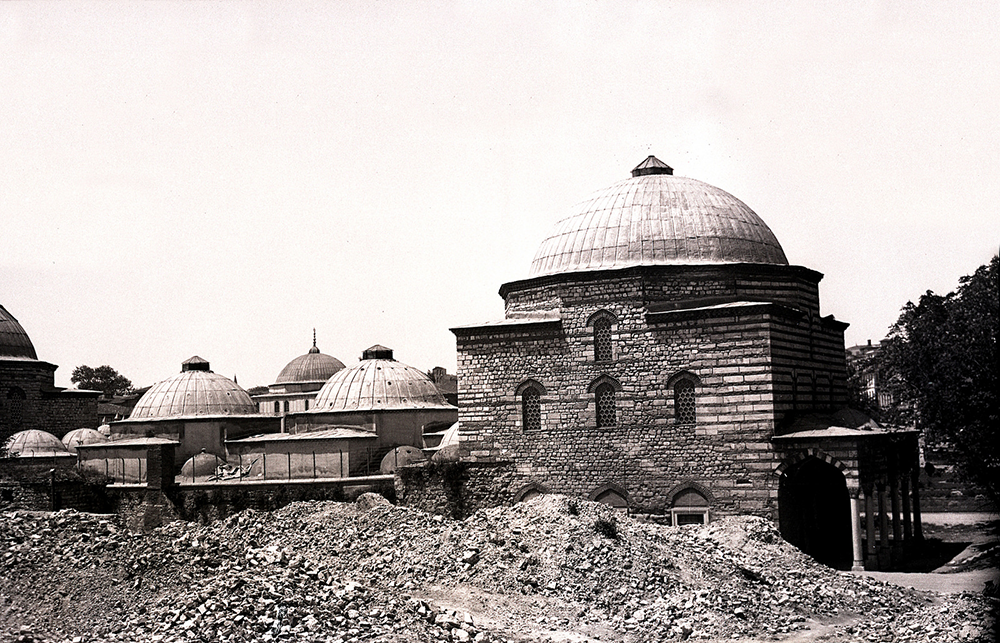

In 1538, construction began on a new mosque in an Istanbul neighborhood somewhat distant from the city’s imperial core. It was the nucleus of a foundation that would soon expand to include two schools—a madrasa to provide advanced education to older youths and a primary school that taught letters and scripture to children of the neighborhood. The next structure to rise up was a large soup kitchen. Some years later, the complex gained a hospital, a rare amenity. A fountain on the soup kitchen’s grounds brought fresh water to neighborhood residents, a further boon.

Roxelana’s Istanbul foundation was the first of the philanthropic efforts that would punctuate the rest of her career as queen of the Ottoman Empire. By the time of her death, major charitable institutions existed in her name in the holy cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem and in the Ottoman capitals of Istanbul and Adrianople, while smaller endowments were scattered across the empire in regional capitals and towns. Works she built or supported financially included hostels for wayfarers, pilgrims, and religious devotees, as well as additional mosques and soup kitchens. Roxelana also attended to the second face of Ottoman piety, the mystical, by building sufi lodges and mosques for revered spiritual leaders. But her first project was the most significant, for it was Roxelana’s debut as a public servant.

Charitable giving was an obligation for all Muslims who had even a small amount of disposable income, and the Ottoman dynastic house was expected to lead. The great Istanbul foundations of Mehmed the Conqueror, his son Bayezid, and their leading statesmen had forged the recovery of Constantinople after its decline in the late decades of Byzantium. Roxelana recognized that undertaking a substantial philanthropic project was the single most effective means of legitimating her extraordinary elevation to queenhood. If anything would win the hearts and minds of Ottoman subjects in a lasting way, it was a graceful edifice that offered tangible benefits to ordinary people.

For Muslims, such donations to the public welfare were hayrat, good deeds or good works that won merit in God’s eyes. Obituary notices of prominent figures regularly included their record of philanthropic projects. In other words, the users and admirers of Roxelana’s mosque complex would recognize—and respect—an intentional act of piety. At the same time, both subjects and foreign observers of the sultanate understood that her foundation was a display of power. In a culture that disapproved of physical representation of the sovereign on statues and in portraits, even on coins, monumental architecture was the most obvious demonstration of wealth and influence. Like the foundations endowed by the sultans and many of their viziers, Roxelana’s eventually gave its name to the area in which it was located—today the busy Istanbul district is officially known as Haseki (the royal favorite).

For prominent women, who did not reveal their persons openly in public, building was an even more consequential gesture. Although her wedding had been celebrated, Roxelana enjoyed no public coronation like that in May 1533 of her contemporary Anne Boleyn, the favorite of Henry VIII. Roxelana was queen by virtue of Suleyman’s desire, as no traditional or legal category legitimated such a position. It was her act of charity toward Istanbul that was both proclamation and justification of her queenhood. It endured long after both Anne and she were dead.

The location and timing of her architectural debut announced Roxelana’s maverick status. Her foundation was the first in Istanbul donated by and called after a woman. Tradition dictated that it was only after a royal mother graduated from the imperial center together with her son that she acquired the privilege of public patronage. Her projects tended to be located in or near the province where her son served as governor. And she typically initiated foundations only once her son was well established in his public career.

Philanthropic giving, in other words, was a privilege of mature political motherhood, a status Roxelana had yet to achieve by traditional measures. When the planning for the Haseki foundation began, her eldest son, Mehmed, age sixteen, had not yet departed from Istanbul for a provincial governorship; nor was it clear when he would. Roxelana’s project was only the latest challenge to established dynastic practices already pushed aside to make way for the concubine’s unprecedented ascent to freedom and marriage to the sultan. Moreover, the Haseki was the first foundation constructed in the builder’s own name by a member of the current royal generation. At the outset of his reign, Suleyman had built a mosque complex in memory of his father Selim, but nothing since.

Hindsight allows us to see that the Haseki helped to redirect the momentum that drove Suleyman’s reign. The execution of grand vizier Ibrahim Pasha in March 1536 signaled a shift in priorities. Instead of lavishing resources on the splendor of the sultan’s person, palace, and retinue, political work Ibrahim excelled at, spending would now be conspicuously focused on channeling resources into the public welfare. Roxelana’s philanthropic donations were instrumental in Suleyman’s efforts to consolidate a stronger sunni Muslim identity after his recent victory over the shi`i Safavids of Iran.

Roxelana doubtless received advice in the choice of a site for her foundation, but the final decision bore her imprint. The neighborhood selected for the mosque was associated with females—it held a weekly market commonly known as Avrat Pazar (women’s market). John Sanderson, secretary to the English embassy at the end of the sixteenth century, described it as “the markett place of women, for thether they come to sell thier wourkes and wares.” It must have been unusual for the times, for the neighborhood had come to be popularly, if not officially, known as Avrat Pazar.

Writing a century later, the famous traveler Evliya Çelebi noted that people commonly called Roxelana’s mosque “Haseki Avrat.” Apparently the benefactor, her female beneficiaries, and the neighborhood had become intimately linked in the popular mind. Women of the neighborhood could gain much from the queen’s foundation. Males might be the sole beneficiaries of its madrasa, but women could pray discreetly in the mosque and line up for the fountain’s water and the soup kitchen’s dole. Little girls sometimes attended primary schools, and Roxelana perhaps encouraged coeducation in hers. She herself had had excellent teachers and a cohort of fellow students as she struggled to learn, and she might hope to offer something of the same opportunity to the less fortunate girls in her adopted neighborhood. They lacked the privilege enjoyed by daughters of better-off families, who might learn alongside the brothers for whom private tutors were hired.

That Roxelana had a strong hand in the early planning of the Haseki is suggested by her close oversight after the complex was completed—she appointed herself for the duration of her lifetime to the executive office of endowment supervisor. The careful detail with which the queen specified the qualifications and daily wages of the staff employed in the complex provides yet further proof of her intimate involvement in the implementation of her foundation.

The complex’s Avrat Pazar location raises the question of whether Roxelana had as one of her goals the specific welfare of females. That one of the key administrative positions she specified for her foundation was a female scribe suggests that she did, but we can only surmise her motives. This was an unusual stipulation, since female functionaries of the times were virtually unknown in public institutions. Perhaps the lady secretary’s job was to facilitate women’s access to the complex’s services or to receive their petitions or complaints. It is not hard to imagine a neighborhood woman voicing concern about long lines at the fountain, or asking about her child’s eligibility for the primary school, or perhaps seeking the dole from the soup kitchen.

But how was the female staff member of the foundation trained for the job? The one place in the capital that we know had a staff of skilled female scribes was the harem quarters of the imperial palaces. That a trained scribe put to paper Roxelana’s own letters is evident from their refined penmanship. Even after the queen mastered enough Turkish to write her own communications, she continued to call on the services of a scribe and doubtless kept at least one on her personal staff. Entrusted with intimate or politically revelatory knowledge, a personal secretary was recognized as a confidential intimate, in Turkish a “scribe of secrets.” Some palace staff would also be skilled in bookkeeping and budget balancing as they kept the accounts of high-ranking women’s income and expenditures.

Whether Roxelana was a forward-looking equal opportunity employer or merely wanted a direct hand in the foundation’s business is hard to say—perhaps it was both. But if anyone were to challenge the etiquette of women’s employment, it would be Roxelana, who was busy fashioning an innovative career for herself.

Adapted from Empress of the East: How a European Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire by Leslie Peirce. Copyright © 2017 by Leslie Peirce. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.