Lace panel with Lion of Saint Mark, by Scuola dei Merletti di Burano, twentieth century. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, bequest of Gertrude M. Oppenheimer.

Italian lace was reborn on the Venetian island of Burano in 1872. That year Countess Adriana Marcello and Princess Giovanelli Chigi, with the backing of Italy’s Queen Margherita, resurrected the isle’s famed seventeenth-century workshops. Lace had an august history in Venice and on Burano, where women used needles to create minute buttonhole stitches that blossomed into intricate patterns. Punto in aria, or stitching in air, was supposedly invented in Venice and had long been an extremely precious commodity. Venetian needle lace adorned the cuffs and collars of monarchs and clergy across Europe throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In Italy, lace constituted such a potent marker of class that sumptuary laws prohibited women from wearing more than an allotted amount equivalent to their social rank, and sellers measured lace in ounces or carats as if it were a piece of gold or a diamond. The Sun King himself, Louis XIV, commissioned a Burano lace collar for his coronation: the piece took two years to create and cost approximately $20,000 in today’s currency. Italian needle lace was so coveted that French and Flemish producers began to create similar types on larger scales so that by the 1860s, lacemaking on Burano was largely moribund.

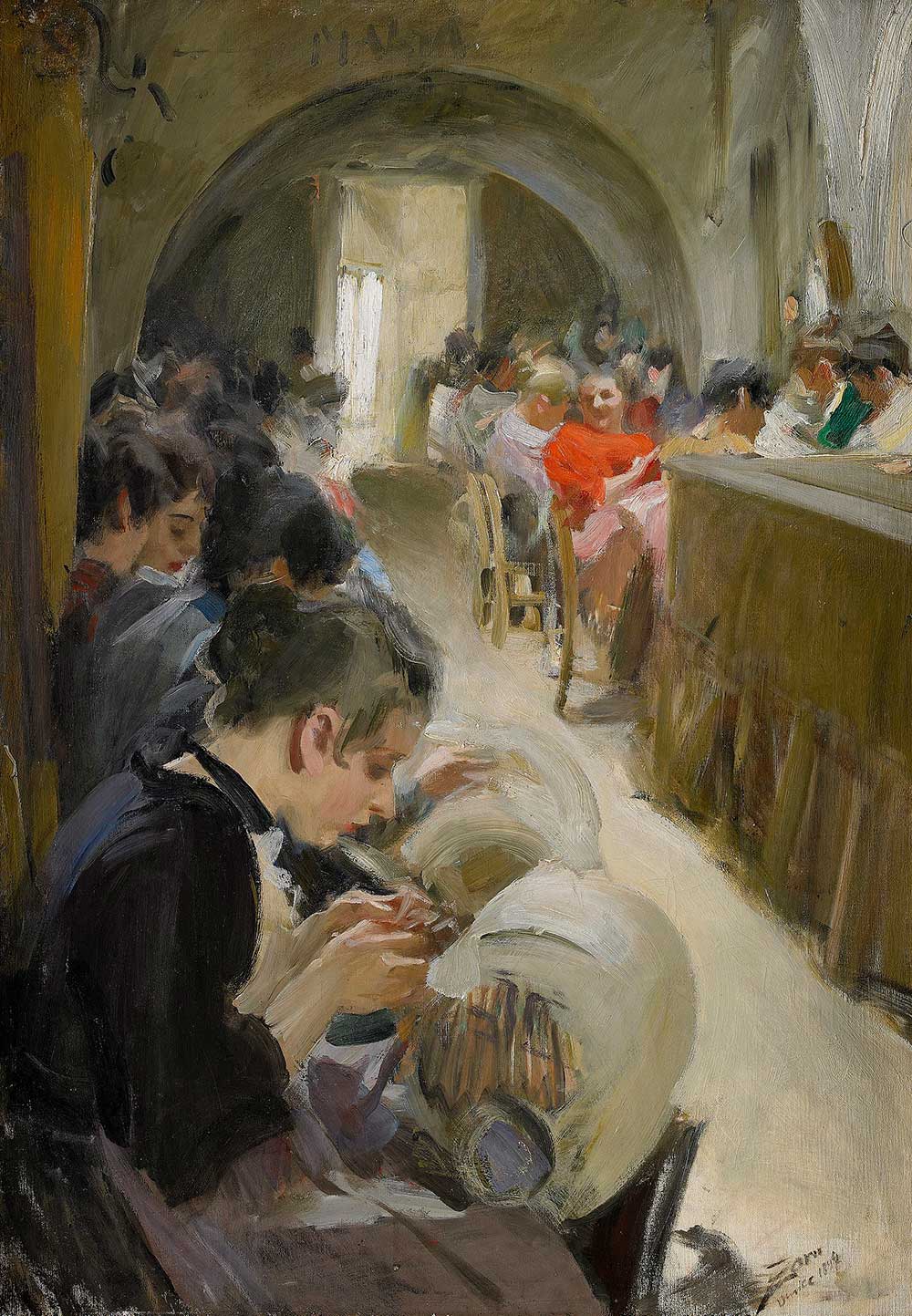

As the story goes, in 1872 only one remaining craftswoman, Cencia Scarpariola, knew how to create Burano’s famed patterns, but she did not have the teaching skills to pass on her craft. Anna Bellorio d’Este, a teacher working at Burano’s school for girls, observed the old woman closely, practiced, and began to teach pupils to re-create Scarpariola’s techniques. By 1900 the Burano Lace School boasted six hundred students and was producing lace in the vein of Venice’s famed antique examples, some even featuring the winged lion of Saint Mark, a nod to the iconic symbol of Venice. One American writer noted that the school produced “only the choicest and most beautiful kinds of lace” and helped a generation of women on Burano earn enough income to purchase homes and bolster their dowries. The women of Burano “made the best possible use of the storehouse of beauty Venice possessed in the old Renaissance patterns” and fashioned new objects inspired by antique designs admired in Italy and beyond.

Like the workshop’s Italian supporters, expatriates Katharine de Kay Bronson and Enid Layard contributed to the school on Burano, intending their philanthropy to support their adopted city. Each also added to the growing literature on Italian lace for American audiences. Layard, whose husband was the Murano glass revival financier Sir Austen Henry Layard, translated a treatise on lace production into English. Bronson published an article in Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine that brought the Burano revival industry to U.S. readers in vivid detail.

Lace was the consummate skilled labor. Traditional lace could only be produced on a small scale and with ample time by trained artists using either a needle or a series of wooden dowels called bobbins. Associated with court culture, the work of lacemaking had, by the late nineteenth century, largely migrated to rural homes and small-scale workshops thanks to the support of a burgeoning group of experts, teachers, and philanthropists. The industries they founded appealed to Arts and Crafts enthusiasts eager to associate products with rural life pursued in concert with the natural world. In Italy, aristocratic families and committed reformers revived lace and embroidery techniques to celebrate a newly formed, unified Italian culture. These industries also provided a means of economic independence for Italians whose agrarian ways of life were disappearing due to dwindling land inheritances and mass migrations northward or to the United States after the Industrial Revolution.

Antique lace collecting and revival lace workshops linked women through surprisingly broad networks of exchange that transcended centuries, continents, and class divides. By charting the translation of age-old Italian lace patterns and techniques into new forms and settings, we begin to understand the migration of ideas, cultures, and people between Italy and the United States in new ways. Wealthy Americans traveled to and settled in Italy and transformed its institutions, just as many middle- and working-class Italians were immigrating to the United States in unprecedented numbers and altering American culture in durable ways, which lace, both old and new, records and visualizes.

Europeans had produced lace since the fifteenth century, but in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the craze for collecting examples from Italy, France, Belgium, and Britain helped preserve an antique art form and encouraged revival industries. The late nineteenth century’s financial, political, and social upheavals, combined with debilitating droughts across Europe, forced many landed families off their estates and increased the circulation of luxury goods such as lace on the open market. Shifting political boundaries also loosened the Catholic church’s grip on vast holdings, so that ecclesiastical textiles began to appear for sale through dealers in Venice, Paris, and New York.

American women living abroad or mindful of international stylistic trends found these meticulously rendered works fascinating and bought them with abandon. As historian Rosanna Pavoni has described, Italian material was of particular interest for upper-class American collectors because “Italy was regarded as the depository of a tradition which sprang directly from the master craftsmen of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.” Renaissance artisanship and its associations with skilled makers and small-scale, guild workshops suited collectors enamored of the Arts and Crafts movement and its emphasis on the handmade.

Every consequential Gilded Age doyenne, it seems, collected lace. Isabella Stewart Gardner, Arabella Huntington, Jane Morgan, and Charlotte Schermerhorn Astor all maintained extensive collections, many of which eventually found their way into public institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the United States National Museum (now part of the Smithsonian Institution). The market for these materials was cutthroat, with collectors on both sides of the Atlantic vying for fragments and offering tremendous sums of money to secure them. In 1895 writer Maud Howe Elliott declared, “Old lace is now almost priceless; there has been a tremendous run on it…Most of the good old lace has gone to America.” The New York Times compared Italian laces to fine oil paintings and remarked, “The market price for a flounce of old Venetian point is $1,000 a yard…It is so rare that it is registered like a fine old Rembrandt and like the picture the location of a Venetian point flounce is known to collectors and dealers all over the world.”

Many female collectors focused solely on lace, creating a comparably high-stakes corollary to the male-dominated market for old master paintings. American women amassed fragments for use as clothing and as household decoration, but also systematically for study and presentation. As The Queen Lace Book noted in 1874, “Formerly lace collections were hidden in presses and cabinets, now they are for public inspection.” Wealthy American socialite Rita de Acosta Lydig acquired an admirable collection of antique lace and employed Europe’s finest designers to transform her collection into stylish outfits showcasing the latest silhouettes. Lydig owned more than three hundred pairs of shoes by famed shoemaker Pierre Yantorny, many of which he adorned with fragments from her storehouse. Isabella Stewart Gardner spent lavishly on her lace collections, paying prices for some fragments that far exceeded what she spent on Venetian panel paintings. In 1894 Gardner recorded spending a staggering $2,860 for an “old Rosalino point flounce” and $413 for an “old handkerchief and coverlet.” She purchased examples from dealers and through connections to fellow Americans in Venice, such as Bronson and her daughter, Edith, the Countess Rucellai. Gardner was the type of educated collector who put together a well-respected group of laces for decorative purposes but also to display as art objects in her museum. Even as she commissioned seamstresses to combine fragments into curtains that divided the grand second-floor chamber and the central court of her purpose-built museum in Boston, she also featured individual examples in glass cases within the galleries themselves. Like many of her peers, Gardner also collected revival textiles alongside antique materials, acknowledging and celebrating the enlivened interest in leveraging aspects of Italy’s past to bolster its present.

The collection and classification of antique lace fragments gained popularity with elite American collectors through manuals, largely written by women, that helped buyers identify various techniques and regional characteristics. Fanny Bury Palliser’s 1865 History of Lace weighed the value and rarity of various forms. Reprints of antique pattern books such as Cesare Vecellio’s 1591 Corona delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne also popularized Renaissance designs among makers and collectors. In 1908 Italian writer Elisa Ricci produced a richly illustrated three-volume guide to Italian laces, Antiche Trine Italiane, a work that presents a chronology of forms illustrated with examples from private collections in both Italy and America. In 1920 Metropolitan Museum textile curator Frances Morris and Marian Hague published Antique Laces of American Collectors, a publication that detailed the history of European textile collections in the United States in public institutions and private hands. In the United States, associations such as the Needle and Bobbin Club and a journal associated with the group also sprang up to bring together upper-class women with shared interests in fostering antique lace appreciation and supporting the production of contemporary textiles.

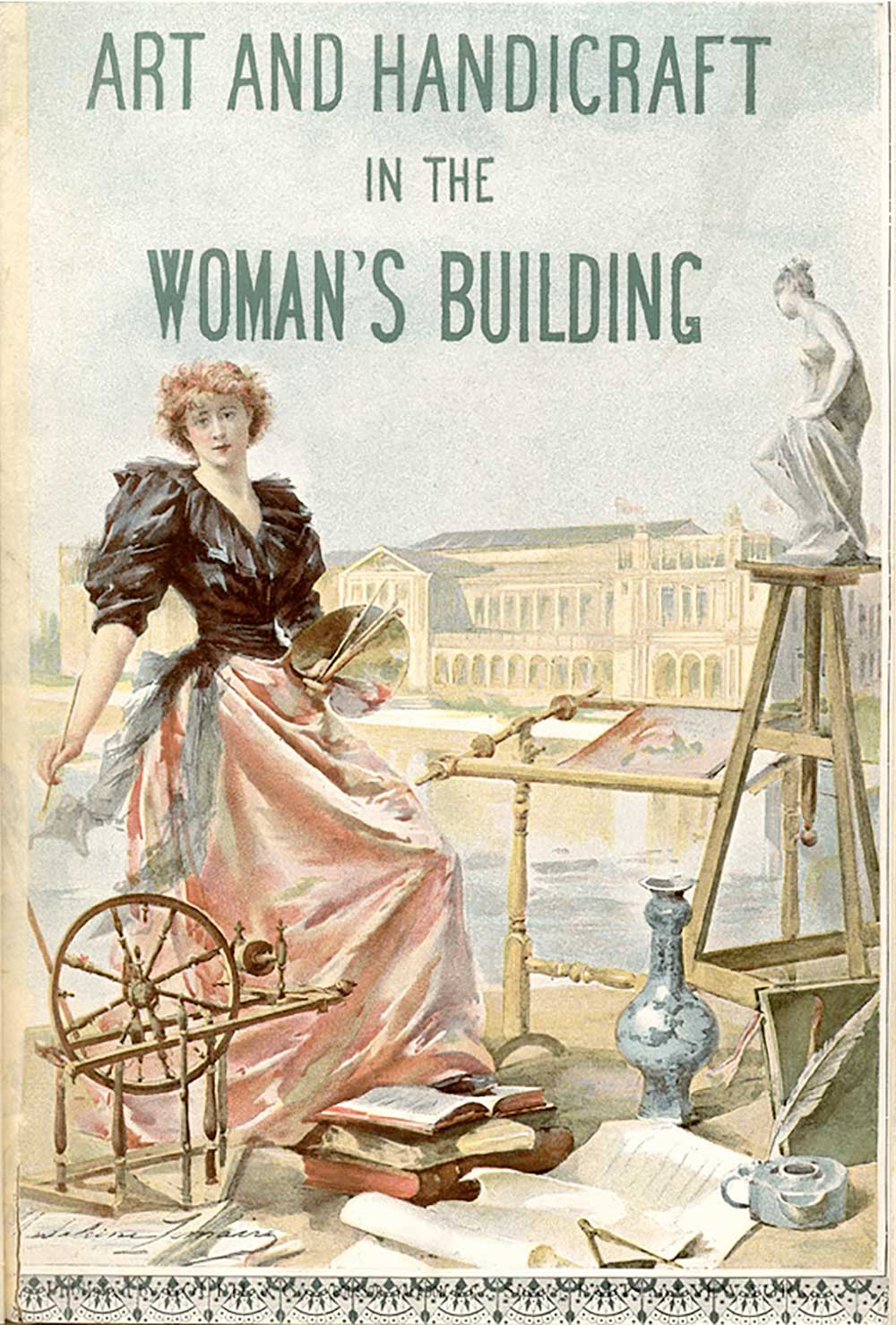

Americans’ interest in lace also peaked thanks to its prominent presentation at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a premier venue for art and craft display. Collector, Italian workshop director, and American expatriate Cora Slocomb di Brazzà shepherded Queen Margherita of Italy’s prized collection of historic and contemporary textiles to Chicago for the festivities and oversaw their installation in the Woman’s Building. The array of finely worked examples celebrated the history of lace from blocky sixteenth-century reticella to figurative baroque needle and bobbin laces. On view within hand-carved wooden and wrought iron constructions evoking Renaissance architecture, the displays offered examples “from prehistoric times to the most perfect specimens of the modern school of Burano,” positioning lace as the epitome of Italian craftsmanship past and present. As historian Hubert Howe Bancroft observed, “These are heirlooms descended through many generations, some of them articles the secret of whose manufacture is known only to the royal household, and others samples of varieties which the queen is introducing among the women of Italy, reviving an industrial art that was well-nigh lost.”

As private collections coalesced and lace went on view at major international expositions, museums across the United States also began receiving donations and exhibiting antique European lace. The Metropolitan Museum of Art received its first major lace collection in 1879 and augmented it at intervals until 1938, by which time its holdings had mushroomed to well over four thousand objects. The Met’s list of lace donors reads as a veritable who’s who of New York society with names such as Astor, Bliss, de Forest, Harkness, Morgan, and Skyler. In 1921 the Met had two full galleries dedicated exclusively to lace, suggesting the medium’s tremendous popularity. True to its founding mission as a space to inspire working-class craftspeople, the museum also welcomed visitors to examine materials up close in the Textile Study Center. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin declared, “Here one may study the history of lace from its primitive conception in the Coptic network of the early centuries of the Christian era to the highest perfection of the art in the Venice points; and from this stage one can follow its development in the different countries under varied conditions, each with its marked characteristics, but few attaining the perfection of the early Venetian workers.” As lace gained importance in American art institutions, a small group of experts also entered curatorial departments to care for and enlarge the collections. The craze for lace ushered in the first generation of American female museum professionals, women such as Frances Morris at the Met and Sarah Gore Flint Townsend at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, both of whom rose through the almost exclusively male ranks to maintain and augment these materials with the help of European experts such as Carolina Amari. Knowledge of antique lace paved the way for women to enter the curatorial profession with an expertise all their own.

Excerpted from Sargent, Whistler, and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano, edited by Crawford Alexander Mann III. Copyright © 2021 by the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.