Greeting card with four spoonbills, by Theo van Hoytema, c. 1878. Rijksmuseum.

In 1695 the British naturalist and apothecary James Petiver was unsure of the whereabouts of his correspondent John Smyth. He thought that the Royal African Company minister should have long departed Cape Coast, and he had been in “great hopes” of seeing him in London. Surmising that Smyth might still be in West Africa, the apothecary sent one last letter to the Anglican minister by means of a slave ship surgeon bound for the Gold Coast. Petiver thanked Smyth for a collection of African plants that he had sent in 1693 but also confided that a second collection Smyth intended for Petiver had never made it to England. Although Petiver was uncertain whether the chaplain was still at Cape Coast Castle, he was not one to turn down a chance—however slight—to obtain more specimens. Petiver therefore reminded Smyth that he would gladly welcome any further collections he made before departing West Africa. “Rev’d Sr,” the apothecary pleaded, “We having as yet very few either shells or none Insects from that part of Africa where you are I must humbly beg you will be pleased to have some Native or poor man to make me what Collections of these and Plants may come in his way.”

The work of early modern naturalists required that they consult, compare, and analyze natural historical specimens or their visual representations. As Petiver informed Smyth, there were few such specimens from West Africa for British naturalists at the turn of the eighteenth century to consult. Naturalists therefore enthusiastically welcomed—and relied upon—the flora, fauna, minerals, and other objects obtained by British slave ship surgeons, captains, and slaving agents in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The group of British slaving mariners and agents engaged in collecting natural historical specimens was likely small, yet their impact on British natural history was significant. Slave traders and mariners collecting on behalf of British naturalists, in turn, relied on Africans as guides, informants, collectors, and knowers.

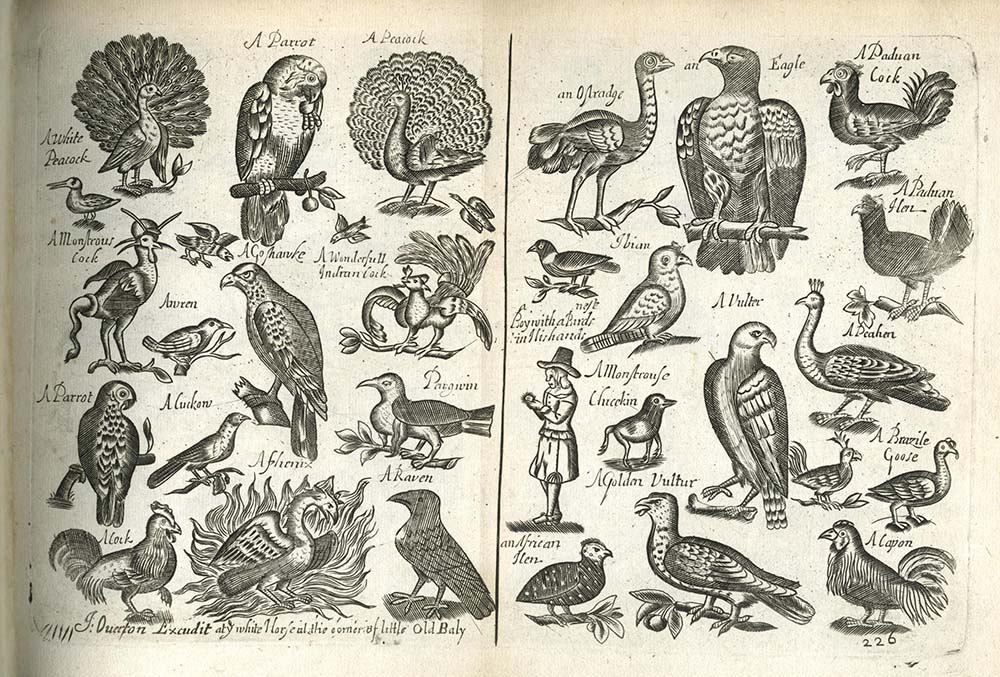

A specimen gathered by a Fante person in the Gold Coast, then acquired by a British slaving mariner, transported on a slaving vessel to an American port of disembarkation and then to London, might find its way into the collection of a metropolitan naturalist and eventually into the Royal Society’s meeting rooms in Gresham College. There, naturalists such as Petiver and Hans Sloane presented the specimens and observations obtained by means of the British slave trade to the assembled members of the learned society. In December 1698, for example, Petiver “produced a Strange leaf from Calabar in Guinea” that was “perforated after a very odd manner.” The following year he displayed the bill of the African spoonbill and a cashew nut “from Guinea.” Later that same year Sloane reported that “Cap’t Forty” (likely Captain Henry Forty of the slave ship Neptune) described the mouth of the Gambia River as “accessible and wide Enough, without Shoal, for a Ship to go up, and he added that in the Country thereto belonging, there are Ostriches.” Petiver regularly presented specimens he obtained from slaving mariners, including the Anglo-African company agent Edward Bartar, during meetings of the Royal Society, often elaborating on the descriptions he provided in his published accounts of the same objects. For example, he noted that the specimen of “Bartars dark Guinea Butterfly with white spotts” displayed before the society was “of the same magnitude and delineation” as the one he had published in his natural history Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis. The naturalist added that the wings were transparent “if held to the light” and that the body “sparkles with white on a black ground.”

Specimens gathered along the routes of the slave trade were regularly shared, bartered, and borrowed among British naturalists. The English physician and naturalist Martin Lister, for example, borrowed African specimens from Petiver’s collections to complete his masterpiece on conchology, Historiae Conchyliorum. The botanist Leonard Plukenet described Gold Coast plants gathered by Bartar in his Almagestum Botanicum. Similarly, the herbarium of plant collector William Sherard included a plant gathered by Bartar near Cape Coast Castle even though there is no evidence that Sherard directly corresponded with the slaving agent. Specimens gathered along the routes of the British slave trade continued to circulate among and be consulted by British naturalists long after the means of their collection were forgotten. Herbaria specimens sent by Smyth, for example, were used in a recent study comparing historical and contemporary ethnobotanical knowledge of Ghanaian plants.

Specimens obtained by means of the British slave trade were also described and depicted in metropolitan naturalists’ publications. Early modern naturalists regularly relied on images of specimens in the course of their studies. The illustrations in Petiver’s texts were modest compared to the lush engravings found in other natural histories of the period. Yet they still allowed European naturalists to study specimens that they likely would never view in person. Decades after Petiver’s death, Swedish systematist Carolus Linnaeus referenced illustrations from the apothecary’s publications in order to classify various African species. For example, slaving surgeon Richard Planer obtained a West African moth “from the Guinea Coast” around 1700, which he gave to Petiver. Petiver described the moth as “Phalaena Guineensis flava perelegans & pulchre oculata” and included an image of it in Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis. Half a century later, Linnaeus used this image to define the species he called Phalaena paphia. Through the circulation of images, a specimen gathered by slave ship surgeon in West Africa could serve as the basis for taxonomical study decades later. In similar fashion, objects gathered by British slaving mariners and agents shaped the development of natural inquiry throughout the eighteenth century and beyond.

West African specimens played an important role in establishing Petiver’s reputation as a naturalist. The collections that Smyth sent from Cape Coast Castle in 1693 became the basis for Petiver’s first contribution to the Royal Society’s journal, Philosophical Transactions. “A Catalogue of some Guinea-Plants, with their Native Names and Virtues; Sent to James Petiver, Apothecary, and Fellow of the Royal Society” appeared in 1697, just two years after Petiver’s election to membership in the Royal Society. The society promoted itself in the late seventeenth century as a clearinghouse for useful knowledge and aspired to catalog the world’s natural productions. “Catalogue of some Guinea-Plants” thus provided a means for Petiver to prove himself worthy of his election by publishing descriptions of over three dozen Gold Coast plants at a time when specimens from West Africa were difficult for English naturalists to obtain.

As the title indicated, “Catalogue of some Guinea-Plants” indexed West African plants and “their Native Names and Virtues.” Enslaved or free Fante peoples living along the Gold Coast likely selected, gathered, and preserved the forty specimens described in the text. Each entry began with the name by which Smyth reported the plant was known along the Gold Coast. It then briefly described the preparation and use of medicaments derived from the plant. Most of the entries included additional information such as Latinate classifications, citations to natural historical or medical texts, or morphological descriptions. Each entry ended with Smyth’s name or initials. For example, the first entry explained that aclowa, “so called by the Natives in Guinea, dried and rub’d on all the Body is good for the Crocoes (or Itch.) Mr. John Smyth.”

The title Petiver himself most frequently used for the text—his African or Guinea materia medica—framed it as a practical guide to medical substances along the Gold Coast. Petiver had a professional interest in West African drugs as an apothecary and would have known well the growing global market for medical substances. Further, a “Guinea materia medica” served the interests of British commerce and colonialism at a moment when British slaving along the West African coast was expanding rapidly. “Catalogue of some Guinea-Plants” promised relief to the perennial problem facing Britons in West Africa: how to stay alive in the “white man’s grave.” Although many places in the early modern period had a reputation for having an unhealthy climate for Europeans, West Africa was among the most deserving of such a reputation. “Catalogue of some Guinea-Plants” reflected the principle that one should use local plants to cure local diseases, as well as the pragmatic interest in local healing techniques and knowledges that frequently characterized the behavior of individuals navigating a new or deadly disease environment. To do so, the catalog relied upon Gold Coast natural knowledges. The text noted, for example, that in Cape Coast, local people used acroe for recovering one’s strength, aconcroba to cure smallpox, and concon for killing worms in the legs. “Catalogue of some Guinea-Plants” informed readers not just which plants to use but also how to use them. For example, it reported that aconcroba should be boiled in wine but that concon should be pounded and mixed in oil. It explained that afto dried and snuffed would cure a headache, that assrumina “pounded and rub’d on the Legs, kileth the Worms that breed there,” and that atanta added to broth gave strength to a sick person.

Petiver simultaneously desired and dismissed the African knowledges that he urged British slaving mariners and agents to collect. The naturalist framed the importance of “Catalogue of some Guinea-Plants” in terms of the “many Advantages” that would be brought “to the Art or Mystery of Physick, if the Vertues of all Simples were more nicely inquired into, or better known.” For naturalists such as Petiver, the process of “better knowing” the virtues of West African plants involved abstracting them from their social, spiritual, and political contexts. Further, Petiver understood that the healing properties of the plants described in the catalog were known among the peoples living along the Gold Coast. He framed West African knowledge, however, as something less than true natural knowledge, declaring that Africans’ “innocent Practice consists of no more Art than Composition.” The naturalist suggested that the Fante had not improved upon the God-given therapeutic properties inherent to plants and, instead, that Fante medical knowledge was limited to rudimentary composition. In actuality, the ethnobotanical systems that developed over generations along the Gold Coast were highly sophisticated and well adapted to their material and cultural contexts. Petiver eagerly sought to coopt and abstract West African natural knowledge while at the same time asserting that it merely represented “innocent” or unknowing practice.

From Captivity’s Collections: Science, Natural History, and the British Transatlantic Slave Trade by Kathleen S. Murphy. Copyright © 2023 by Kathleen S. Murphy. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.