The American Goldfinch and Acacia, by Mark Catesby, c. 1722. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021.

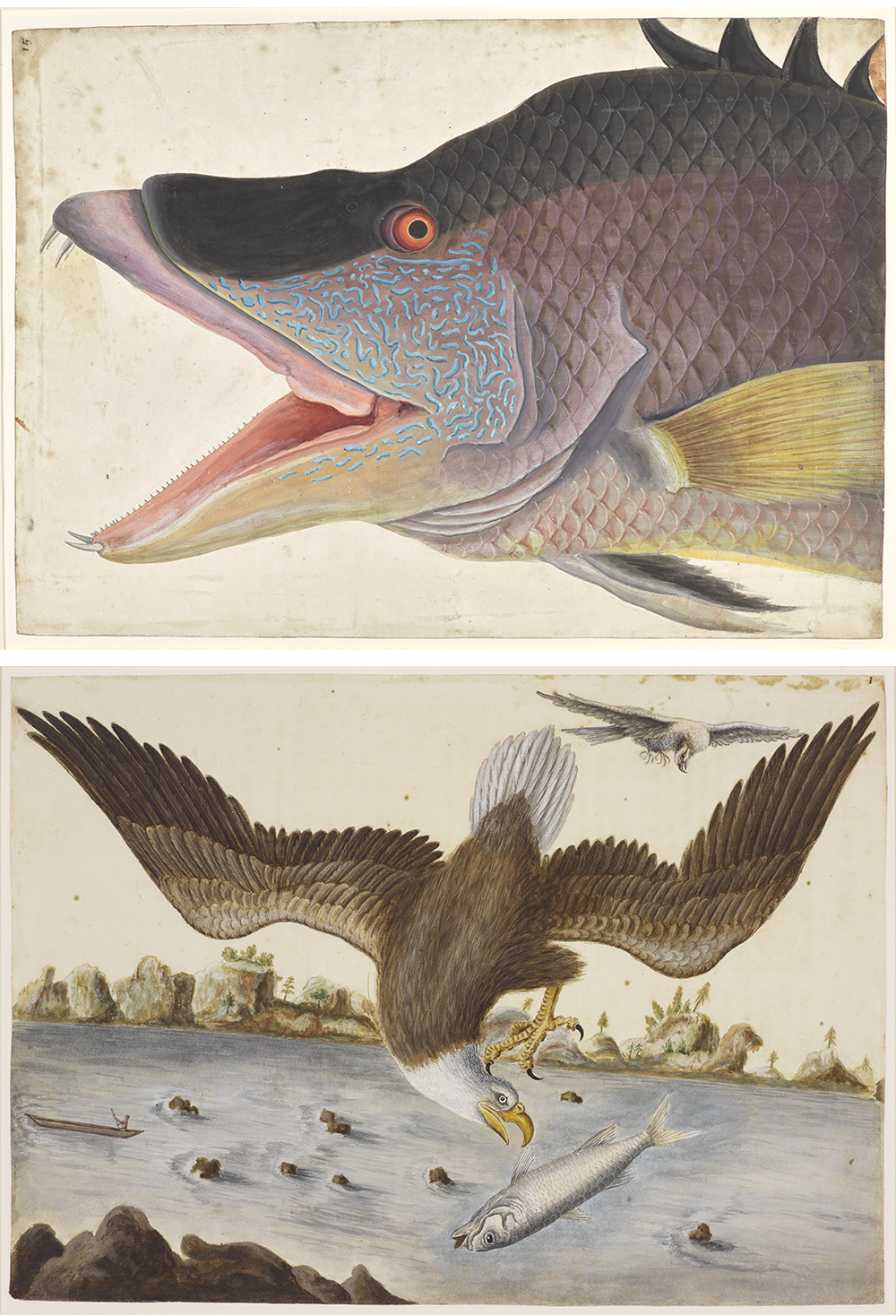

The English naturalist Mark Catesby (1683–1749) began his 1731 Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands with a clear statement about his early vocation to study natural history: “The early inclination I had to search after plants, and other productions in nature, being much suppressed by my residing too far from London, the center of all science, I was deprived of all opportunities and examples to excite me to a stronger pursuit after those things to which I was bent.” What led Catesby to state that London was “the center of all science”?

In 1687, four years after Catesby’s birth, Isaac Newton had published his Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy); and in 1703, when Catesby was twenty, Newton was elected president of the Royal Society of London, founded in 1660 “for improving natural knowledge.” Newton was to hold this position until his death in 1727. Under him, the Royal Society was to lead the intellectual quest for gaining knowledge based on empirical observation, experiment, and verification rather than on classical authority.

Naming and classifying new species for the evergrowing catalogue of nature was one aspect of “improving natural knowledge.” The aim of achieving scientific comprehensiveness existed side by side with the urge to collect rare natural objects and identify commodities for potential mechanical and medicinal use. To these various ends, members of the Royal Society and other wealthy individuals sponsored plant collectors and explorers to travel to America, Africa, and the Near and Far East to collect new material which could then be added to the “philosophical stock” or “general bank” of experimental learning. The material collected was incorporated into collectors’ cabinets, used for medicine and for commercial gain from colonial enterprise.

The Royal Society published detailed instructions about the phenomena travelers were encouraged to observe. Robert Boyle wrote a treatise entitled General Heads for the Natural History of a Country, Great or Small; Drawn Out for the Use of Travelers and Navigators, in Which Information Was to Be Sought Under the Headings of Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms. The apothecary James Petiver in his Musei Petiveriani (1695) directed collectors to follow Boyle’s instructions. The prose style in which the findings of collectors should be recorded was also specified, the Royal Society “preferring the language of artisans, countrymen, and merchants before that of wits or scholars.” The aim was that observations recorded in collectors’ accounts and journals, together with specimens, should provide scientists with a new corpus of objective data on which to build a scientific explanation of the physical universe. Some of this data was published in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and some in books written by the collectors themselves.

Preeminent among the academic botanists attempting to catalogue the enormous number of new species arriving from foreign parts, and to incorporate them (with cumbersome Latin polynomials) into a taxonomy, was William Sherard, known as “the Maecenas of botany” by his contemporaries. After studying law at Oxford, Sherard made three grand tours on the Continent as a traveling companion and tutor, where he came into contact with two of the most distinguished Continental botanists—Joseph Pitton de Tournefort in Paris and Paul Hermann, professor of botany at Leiden. He also traveled and collected plants in Italy, and spent a fifteen-year period in Turkey as British Consul in Smyrna, where he studied and collected the plants of Asia Minor. At his death, he left funds for the founding of the first chair in botany at Oxford, named after him. His magnum opus—his so-called Pinax—was an attempt to “to publish an account of the world’s plants” by updating the list of six thousand plants included by the Swiss botanist Caspar Bauhin in his 1623 Pinax theatri botanici (Catalogue of the theater of plants), with every known species discovered since then. Left unfinished at his death, the ambitious project was taken over by Sherard’s German protégé, Johann Jakob Dillenius, who likewise left it unfinished. The “Pinax” survives as an unpublished manuscript in the Department of Plant Sciences at Oxford, a resonant symbol of the belief that it was possible to make an exhaustive catalogue of the world’s known plants.

Plants were sent from foreign parts in the form of the hortus siccus (literally, dried garden) of preserved, pressed specimens which could then be studied and compared with other specimens in collectors’ herbaria. A labeled herbarium was the essential tool for serious eighteenth-century botanists, “providing a link between a plant’s identity and the evidence of its occurrence at a particular point in time and space.” Live plants in barrels of soil and seeds were also sent by collectors, and these, once propagated, became part of the botanical garden or hortus vivus (living garden). Some of these gardens were kept by naturalists for the purpose of studying rare plants. Others were more specifically for growing medicinal plants.

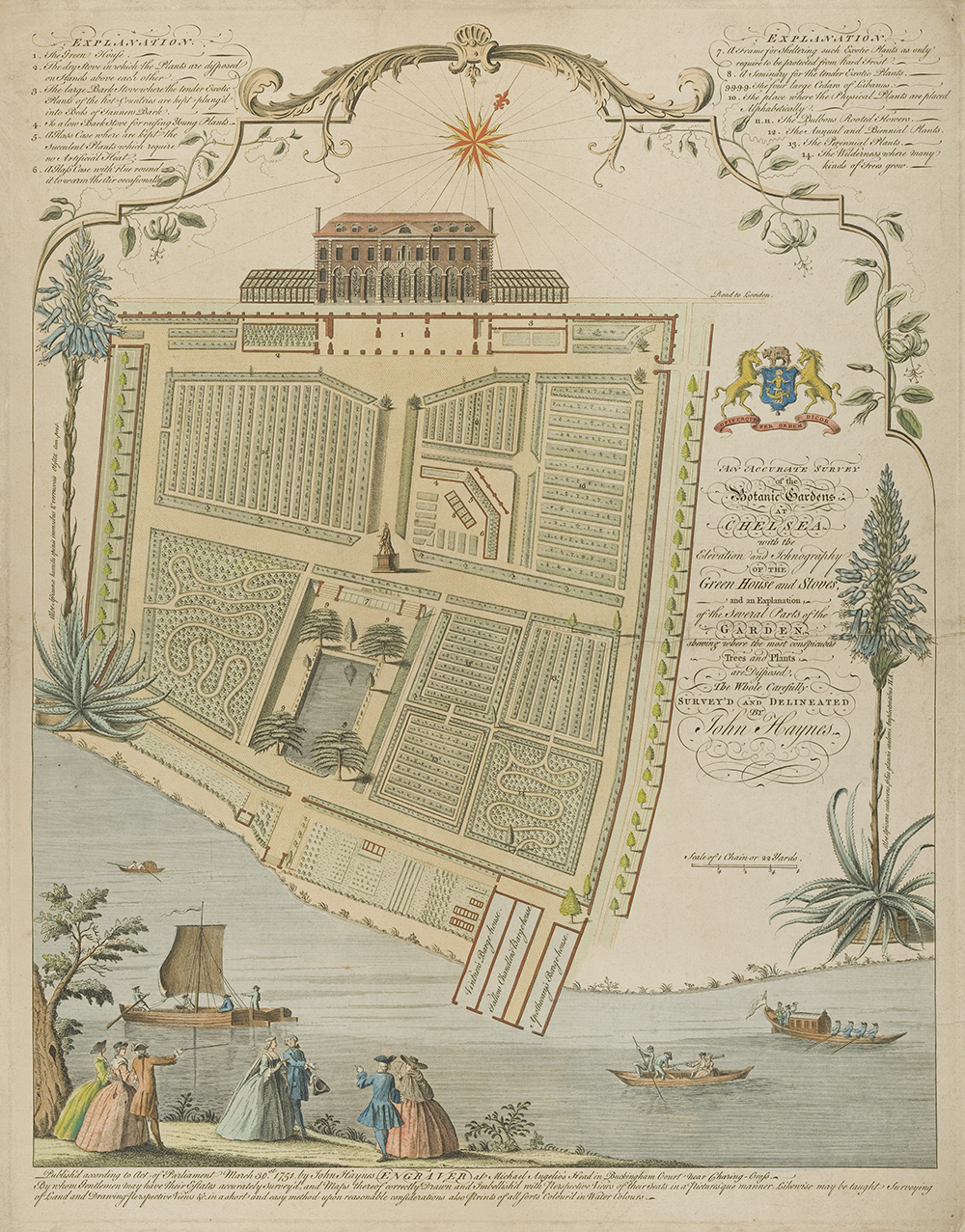

One of the most famous of these dedicated physic gardens was that of the Society of Apothecaries—the Chelsea Physic Garden—founded in 1673 for the purpose of training apprentice apothecaries to study the medicinal plants grown there; the plants or simples from the garden were then processed in the laboratories in the Apothecaries’ Hall at Blackfriars. From 1722 the Apothecaries were required to supply fifty herbarium specimens a year to the Royal Society, and during this period, under the direction of Philip Miller (1722–70), their garden became the most renowned physic garden in Britain and a “pivot of horticultural debate and plant dissemination.” Plants sent from all over the world were grown in the Chelsea garden, and in its turn, it exchanged seeds with other physic gardens such as the equally famous Hortus Botanicus at Leiden.

In 1728, under Philip Miller, a group of the most prominent nursery gardeners based in and around London joined together to form a Society of Gardeners; in 1730 they published the first volume of their Catalogus plantarum, or A Catalogue of Trees, Shrubs, Plants, and Flowers Both Exotic and Domestic Which Are Propagated for Sale in the Gardens near London. Their stated purpose was “to promote the introducing among us such foreign trees, as may contribute either to usefulness or delight,” with the aim also to bring order into plant nomenclature.

Many private owners—both in and outside London—likewise had gardens of rare plants in which new discoveries were prized. One such garden owner was William Sherard’s brother, James, also a botanist, and an apothecary who had made a fortune from his London practice. His garden at Eltham, Kent, then a small village around nine miles outside London, included hothouses for exotics and became renowned as one of the finest in England for rare and valuable plants, containing “many species new to science or little known and never before illustrated.”

The Duchess of Beaufort’s garden at Badminton, Gloucestershire, was another private garden renowned for its rarities grown using newly developed hothouses. The duchess, Mary Somerset, was a serious, self-trained botanist who assembled over a quarter of a century (until her death in 1714) an enormous geographical range of plants, both in her garden and in the twelve volumes of her herbarium. Live plants and dried specimens, which she identified from her extensive library of botanical works, came from as far afield as the West Indies, Africa, India, Sri Lanka, China, and Japan. The duchess employed William Sherard as a tutor to her grandson, no doubt so that she could benefit from his botanical expertise.

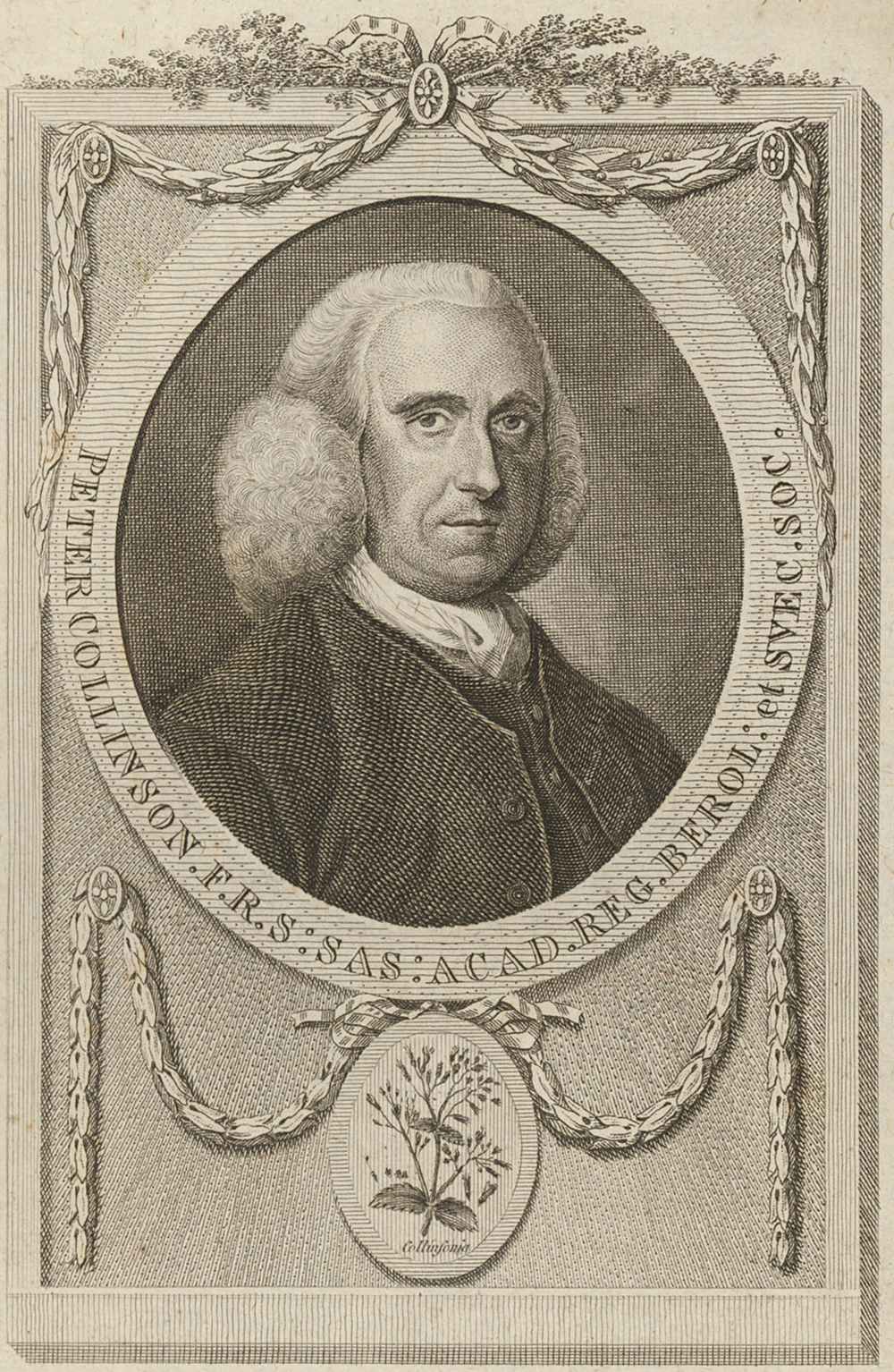

The Quaker merchant and botanist Peter Collinson (1694–1768) was responsible for introducing many new plants into cultivation in his gardens, which became celebrated for their American exotics. His first garden was at his house at Peckham, then a small hamlet south of London; from 1749, he spent two years transplanting his trees and shrubs into what was to become a more famous garden at Ridge House, Mill Hill, Middlesex, a property inherited from his father-in-law. Its contents were later to be catalogued in Hortus Collinsonianus, drawn up from unpublished lists Collinson had begun in 1722. A nineteenth-century biographer was to write, “Natural history in all its parts, planting, and horticulture were his delight. He cultivated the choicest exotics and the rarest English plants. His garden contained, at one time, a more complete assortment of the Orchis genus than, perhaps, had ever been seen in one collection before.” Equally known as a promoter of botany and a friend of everyone in the horticultural world, Collinson himself was to record late in life: “I often stand with wonder and amazement when I view the inconceivable variety of flowers, shrubs, and trees now in our gardens and what there were forty years ago; in that time what quantities from all North America have annually been collected by my means of procuring.”

The 8th Baron, Lord Petre, was at the forefront of the new taste in landscape gardening, to which Alexander Pope was a major influence, both in his poetry and prose and in the example of the garden he created with Charles Bridgeman at Twickenham. Pope’s line “First follow Nature and your Judgment frame” pointed the way to a more natural and “painterly” style to replace the formal taste for geometrical and architectural framing of nature. As part of the new school of gardening, “amphitheaters” of evergreens were created to balance “wilderness” plantations and open parkland, and straight lines replaced by serpentine shapes and vistas on to rolling landscapes. Petre was perhaps the most ambitious of the nobleman garden enthusiasts, and his garden at Thorndon Park in Essex became renowned for its rare trees and shrubs and stoves (heated greenhouses) for tropical plants.

North American shrubs and trees were supplied by the nursery trade and collectors. In addition, Collinson established a scheme whereby John Bartram, a Quaker farmer in Philadelphia, supplied seeds and seedlings at five guineas a box to wealthy English garden owners. As Collinson observed, “The present excellent taste of the nobility and gentry to embellish their plantations with all the variety of trees, shrubs, and flowers which are produced in our North American colonies has given great encouragement to the annual importation of plants and seeds which arrive here in the spring months.” Collinson recorded that Petre “planted out forty thousand of all kinds of trees to embellish the woods at the head of the park on each side of the avenue to the lodge and round the esplanade…His stoves exceed in dimensions all others in Europe.”

When Petre died of smallpox in 1742 aged twenty-nine, Collinson wrote to Linnaeus that his death was “the greatest loss that botany or gardening ever felt in this island,” adding that “he spared no pains nor expense to procure seeds and plants from all parts of the world, and then was as ambitious to preserve them.”

Collections of rare plants in gardens were complemented by collections of rarities of all sorts indoors. The Royal Society had a repository from soon after its foundation. Many of the objects were displayed in a room lined with cabinets, fitted with drawers below for small objects such as fossils and shells, and glazed above to display the larger items on shelves, including varnished “animal parts” and mounted animal skeletons. Members were allowed to borrow items, but the repository suffered from the lack of a curator, and its contents fell into a state of disrepair. When Zacharias von Uffenbach saw it during his visit to London in 1710, he noted: “Hardly a thing is to be recognized, so wretched do they all look.”

Excerpted from Illuminating Natural History: The Art and Science of Mark Catesby by Henrietta McBurney, published by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Copyright © 2021 Henrietta McBurney. Reprinted by permission of the Paul Mellon Centre.