Greggs, Tonbridge, Kent. Copyright © N. Chadwick, via Geograph.

Dan Fox is the author of Pretentiousness: Why It Matters and co-editor of frieze. Lynsey Hanley is the author of Estates: An Intimate History and, most recently, Respectable: The Experience of Class. Fox and Hanley recently talked about growing up in England in the 1980s and ’90s—both were born in 1976—and their own experiences of culture and class, then and now.

Dan Fox: I was struck by an observation that you made in Respectable about how it was never a good idea to appear to be too keen at secondary school. To appear keen, trying too hard academically or creatively, would mark you out as being a swot. You write about lads in class affecting disinterest in what was around them, turning everything into a joke, aside from the dynamics of their own friendship group, and you have a sophisticated, empathetic reading of their behavior.

Lynsey Hanley: It’s a tension between social solidarity and wanting to express your individuality ultimately, isn’t it? One of my ambitions with the book was to critique elements of the political left and the political right that try to box in and label people who all the way through their lives—depending on what circumstances they’re in at any given time—are always caught between two poles. On the one hand, working out how much you can be yourself, do something risky, whether that’s in terms of dress or learning about something that’s not generally known about in your milieu and so on. At the same time, wanting to keep your friends and not wanting to take so many risks that you become completely alienated from what you do know. That was a constant theme when I was growing up. It sounds from your book that we went to fairly similar schools at around the same time—the late 1980s, early ’90s, would you say?

DF: Exactly. I started at comprehensive school in 1987, and my experience sounds similar to yours. There was a varied class mix at my school. The area of Oxfordshire that I grew up in is part of the commuter belt for London, so there were kids from well-off, middle-class families at school, but not affluent enough to be sent to private school. There were also pupils from working-class areas, such as Barton, on the eastern edge of Oxford. And then kids from local farms, small rural villages, and the council housing in my village.

LH: You describe in the book a depressing binary divide between Casuals and Goths. Would you say in hindsight that these pop cultural divisions reflected the class differences?

DF: Yes, but it was not a precise demarcation. The Goths—which was the term used in my school for anyone into indie bands—were mostly middle-class, and the Casuals, who were aligned more with rave and dance music, were largely working-class. But in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when the Manchester scene was quite popular across the country, you got some curious crossovers. Goths were getting into rave, and, vice versa, Casuals were getting into guitar bands such as the Stone Roses or Happy Mondays.

LH: I remember Oasis filled that role as well. They were the last truly, massively successful working-class guitar band. But the connotations they brought to that ended up being really depressing. They were making a point of having a go at anything that they regarded as pretentious, at anything that recognized the potential for creative ambition. They were colluding in keeping people in their boxes.

DF: Which is ironic when you think about how much they heroicized the Beatles, who were a truly inventive working-class band, unafraid of experimentation, of moving in avant-garde art circles, for instance, or spending time with Indian classical musicians.

LH: But what the Beatles did is like what David Bowie also brought about: it’s the idea that you could be a totally unremarkable person, from a totally unremarkable place, and then suddenly you could get to do the most amazing things. Do you think that, given that we’re the same age, we grew up in a unique period of media in Britain that brought our attention to a wider range of ideas which, despite today being an age of mass availability of information, people now don’t get exposed to?

DF: We did grow up during a unique phase in British culture. We were teenagers before the Internet and TV on demand. Broadcast media in Britain at that point was narrowcast. We had four TV channels until the late 1990s, when Channel 5 started, and then just four national radio stations, plus local radio. No digital channels, no cable, and—although it was available—I didn’t know anyone who had satellite TV. For me, this lack of choice had happy educational side effects. Stuck inside on a Saturday night all that was on were the football highlights on BBC 1 or snooker on ITV, and I hated sports. My parents didn’t own a VHS player, so what else was there to watch? It was Alex Cox on BBC 2, presenting a Jean-Luc Godard film for Moviedrome, or they were showing Derek Jarman’s Blue on Channel 4. It provided a brilliant cultural education for someone like me, but it was almost an incidental one.

LH: Do you think you came to write a book about pretentiousness because of your exposure to that wide range of culture, accessed through the normal amount of media that was available at the time?

DF: It’s certainly one reason. I did not grow up in a remarkable place. I didn’t have a private education. Although my parents didn’t have a great deal of money, they did, however, encourage me and my brothers to follow our interests, and that was invaluable. One of the points that I wanted to make in the book is that pretension is so tangled up with assumptions about class. The assumption that if you are interested in, say, art house films, you must be higher up the class ladder, or that you’re aspiring to climb that ladder, just seems absolutely ridiculous to me. That an interest in art, music, film, and so on is representative of self-serving class ambition, of getting ideas above your station, rather than having a curious mind. I’ve got friends in the art world who grew up in lower-middle-class or working-class families who had experiences similar to mine. They got into David Bowie or Pop Art because the books they read at the local library, or the records they heard on the radio, caught their imagination. These were windows onto other worlds, and an interest in them was not a put-on.

I was struck by the passage in your book in which you talk about the band Broadcast and how, the first time you heard them, you could not believe that the area of Birmingham you grew up in was being mentioned in the lyrics of a song that you were hearing on the radio. Your book describes a journey, a class migration, from your origins on a council estate in Birmingham through to a middle-class life now. You write about hoping one day you’d be living a life where you could talk about intellectual ideas and culture and not feel embarrassed or under threat from the groupthink for doing so. But how did culture function for you?

LH: I definitely have an overactive imagination, and I had an early exposure to a lot of media because I learned to read very early—I was reading the papers at an inappropriately early age [laughs]. But I also had this sense that I just didn’t seem to fit in. And so I developed this sort of Shangri-La idea in my head, that one day I would get to this place and it would be a reality in my life as well as just in my head. And that was always quite a sort of desperate, propulsive idea, really.

DF: There’s a real emotional force to the description you give in your book of your first day at sixth-form college, where you hoped to fit in, and yet felt different there as well.

LH: On the surface I seemed to fit in straightaway at sixth-form college, partly because everybody liked indie music and I’d never met anybody who liked indie music before. Everybody was very polite and nice. I made friends quickly. But they were all from the other side of Solihull, from the posh parts of town. I just couldn’t get my head around the fact that everything I’d always hoped for, I would get to do, but it would take literally going outside of the council estate in order to make friends and find like-minded new people. That happened. I met people who I am still friends with now, nearly twenty-five years later, but I had to undergo a complete cultural re-immersion in order to get up to speed with their ways of doing things, their milieu, their expectations. I felt accepted as a person for the first time in my whole life, but still my life was completely different to theirs. I think the extremity of this transition—from a totally working-class environment to a totally middle-class environment—brought about the central preoccupation of my life since then, which is the question of where you fit in and what class has to do with this.

DF: You describe it in the book as learning to speak middle-class. I had a similar experience going to Oxford University. I grew up as a townie outside Oxford, which was the nearest city to my village, about ten miles away. I never knew what went on behind any of those beautiful, ivy-clad college walls in the city. My experience of Oxford was the Our Price record shop, WH Smith’s newsagent, Blackwell’s Bookshop, the public library, the shopping center, and the Covered Market. The city’s tiny Museum of Modern Art felt like the threshold to another world of experience, although I used to just like going to the café there, maybe browsing in the bookshop. Even when I was old enough to go to the pub in Oxford, I went to townie pubs, never the student ones. And then when I became a student it was as if I had entered some sort of Jorge Luis Borges short story, discovering a city within a city.

LH: Exactly! Reality almost turns inside out.

DF: I was in the exact same city but suddenly inhabiting different buildings and going to student pubs and experiencing it in a completely new way. I found myself in an environment alongside many people from affluent or upper-class backgrounds, and some of these people have remained my closest friends of the last twenty years. But I remember how my cultural knowledge—of art, music, and so on—was the only currency with which I had to trade initially, because I didn’t have similar social experiences to share.

LH: Having moved to the U.S., would you say there are comparable examples?

DF: The U.S. clings to the myth that there is no class system and that it’s a meritocracy. People don’t talk about class in the same way in the U.S. as they do in the UK, but it certainly exists and intersects with issues of education, geography, race, and immigration in particular, which become other ways of talking about class.

LH: Was it going into the art world that led you to want to write a sort of survey of pretension?

DF: I know a lot of artists, critics, art teachers who have dedicated their life to what seems to be quite an esoteric and often opaque world, full of hard-to-learn codes and languages. And the great majority of people I know who work in the art world do not make a lot of money. Some have independent means that allow them to survive, but many struggle to get by, and yet they are totally dedicated to contributing to this area of culture, wrestling with many political and social contradictions that the art world throws on to them. And so whenever I would read one of the newspapers back in the UK—and interestingly it was almost always one of the middle-class broadsheets—and come across an article fulminating about contemporary art being a waste of the taxpayers’ money, or a con job being pulled on some illusory “Great British Public,” that word pretentious would always come up. And I began to think about the gap in perception between what I knew of the people who are making this stuff and what these commentators writing about it argued was going on. The idea that it’s a great big conspiracy—that we all meet up in a Masonic Temple one mile beneath the Tate with Damien Hirst and plot to overthrow the world using Jeff Koons artworks—is a narcissistic, paranoid, and facile fantasy, and I wanted to make a counterargument to that. As I started compiling examples of the word pretentious in use, I started to detect much more pernicious subtexts. For instance, the number of times you see the word pretentious bolted onto the words foreign film suggests an underhanded way of being xenophobic and classist—the idea that if you enjoy films in a language other than English, you must both be unappreciative of Anglo-American culture and think yourself the type of person who is better than other people because you speak French or Italian. I wanted to put a bomb under that way of thinking.

LH: What you’ve got to in the heart of the book is the fact that the accusation of pretension comes from all sides. From the likes of populists such as Nigel Farage or Donald Trump but also supposedly open-minded liberal commentators such as Andrew Marr, whom you describe criticizing people like the musician Momus for having a Japanese girlfriend and enjoying contemporary art. The accusation comes from the left and the right, it comes from above and below, squeezing people who are daring to try to do something different.

DF: The media perpetuates these attitudes, and you write brilliantly about your youth through the lens of the British media. You talk about the 1980s and ’90s partly through headlines from newspapers such as the Mirror. How does media construct class and the experience of it in Britain?

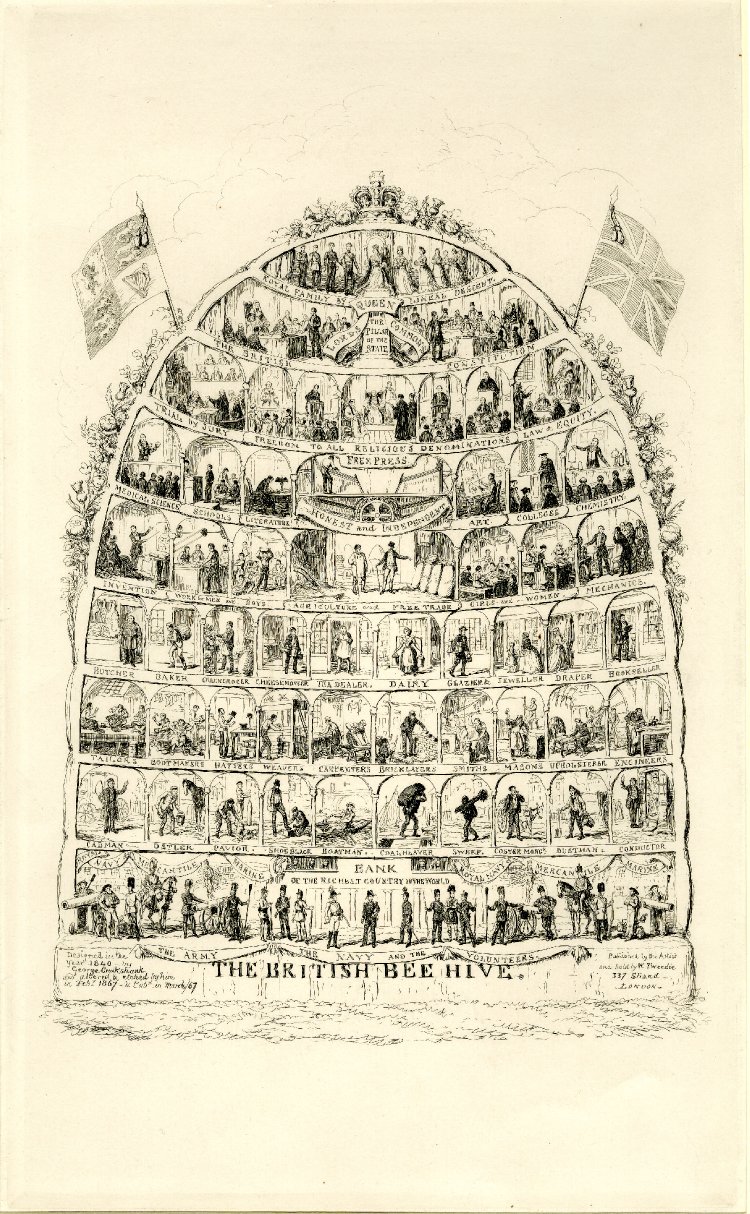

LH: I was keen to try and reclaim individual experience, to reclaim its “sovereignty” [laughs]—that word, with all its connotations. I wanted to retain the perspective of the individual mind in order to think away from, crudely speaking, both a left-wing position of total solidarity and a right-wing one of absolute individualism. So much of our understanding of what you should think, basically, comes from the fact that we have different newspapers for different places on the class spectrum. You’ve got the Daily Star, whose readers are more likely to come from class DE—unskilled working-class and nonworking, using the NRS social grading system. Then you’ve got The Sun, which is more C2—skilled working-class. Then more people from C1, lower middle-class, read the Daily Mail. And then you’ve got all the broadsheets—The Guardian or The Telegraph—which cater to A and B, the middle and upper-middle classes. And there really is one for each place on the ladder. And if you just stick to those papers, then you get a class-specific view that’s based around what you’re told is right to think for someone of your social group. We have the red-top papers as the working-class papers: “We’re all the working common man, everybody goes to the toilet in the same way.” And then the Daily Mail: “You must live in fear all the time!” And that means living in fear of foreigners, it means living in fear of middle-class people who want to destroy the social fabric with their liberal ideas. And then of course the broadsheets have, nominally at least, this sense that they’re above all that. You know, “We treat our readers like individuals.” And yet I think if you’ve spent your life reading the tabloids, and come to the Guardian or Telegraph as an adult, then I think it gives you a bit more of a skeptical eye on what they’re trying to do.

I write for the Guardian, and that’s the one I go to every day. But I think there are forms of class-based symbolic violence that it enacts—for example, the assumption that you live in London. And if you don’t live in London, then you must surely want to live in London. Or the assumption that you’re a high-ranking official in the public sector [laughs], and if you work in the private sector then you’re a bit suspect. Or if you don’t know what do with quinoa, then you obviously live on junk food. I mention a couple of these examples in my book; for instance, when somebody writing about Highgate in London describes it as an ordinary neighborhood. No, Highgate is one of the most socially and economically elite places in the whole country. And the person living there writes a column because it’s their ordinary life and so they believe it’s ordinary. They’ve got absolutely no idea how unordinary it is. When contributors to a newspaper come from a set of backgrounds that is too narrow, then symbolic violence goes completely unnoticed because there’s nobody there to challenge it and say, “Hang on a minute, you don’t seem to realize that most people’s lives aren’t like that.”

DF: Even when I was living in London and reading the Guardian, there was a strange kind of cognitive dissonance between opinion pieces that might espouse leftish ideals and what you might find in the lifestyle section, for instance—

LH: “Everybody’s going to South Vietnam this year!” [Both laugh]

DF: Or the joys of restoring a lovely Georgian terrace house in Islington—great if you’ve got a spare couple of million in order to buy one. [Both laugh] It puts me in mind of something that I feel is slowly happening in the British art world, which is tied up again with education. Going to art school in the UK, for instance, used to be an option for people from working-class backgrounds. These art schools fed a more varied class mix of people into the art world. You’d get super posh people, and you’d also get artists from working-class backgrounds. This rub-up could be creative or at least productively volatile. Whereas now, because an education is something that costs money, and because a lot of arts education has had funding cut at a comprehensive school level and been undermined ideologically by the Conservative government, you just don’t get as many kids from working-class backgrounds going into an arts higher education. This has a knock-on effect in terms of the people that populate the professional art world, and so it becomes more homogeneous, class-wise. That creates an echo chamber of the topics that artists make work about. You don’t get any kind of sense of difference or dissent from within the art world itself.

LH: It points to a concentration of cultural capital. If people in certain jobs are increasingly drawn from a narrower sector of society, then it’s going to reduce the number of viewpoints and reduce people’s understanding of each other’s viewpoints.

DF: The subtitle of your book says so much: The Experience of Class. The experience of class is also what shapes your worldview, of course. It shapes your attitude to money but also to so many other factors: your confidence moving in cultural circles, your relationship to community or family, your expectations and what you prioritize in your life.

You write in your book that learning formal codes of middle-class speech brings about a permanent change. So it’s almost like a kind of neural remapping of your brain. Can you talk about your experience of that?

LH: I was careful not to suggest that any of this literally changes your brain because there’s so much kind of discredited pseudo-neuroscience [laughs] around at the moment that I didn’t want to get into that. But at the same time, of course, the change in language does bring about a permanent change in how you meet the world. It has to do with valuing abstract knowledge. In the book I talk about the sociolinguist Basil Bernstein, who argued that working-class people use language in a way that tends to be present tense, based on contingency, based on the present moment, whereas with the middle class, the code elevates ideas to a more formal, universal level. It emphasizes your agency in the world, and it doesn’t accept contingency.

I suppose a more straightforward way of putting that is that the greater facility that you have with language, the more confidence you have in your ability to make things work for you. It affects your whole life.

DF: You write vividly about the details of your upbringing, about the fine grain of everyday life—the way things looked, how things smelled, or the kind of music you were hearing on the radio. That resonated with me precisely because it wasn’t on the level of abstraction. You use examples, such as the way a doughnut tasted at Greggs, where you had a part-time job, as a way of evoking other specifics of class experience.

LH: It’s almost like a sort of synesthesia really [laughs] that I would get with experiences, and I developed a really intense memory of things. Like Proust and his cake [laughs], it just brings to life a whole world of imagining. And I think that is potentially a sort of experience that you can take beyond class, because it’s human.

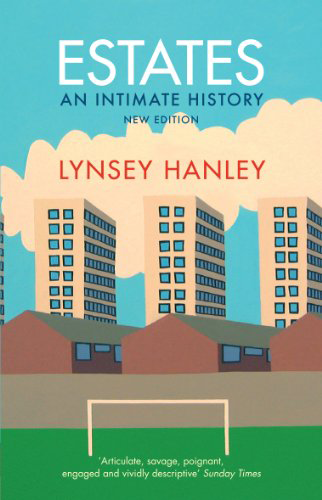

In my first book, Estates, I describe a chip shop next to a playground my mum used to take me to. Every Thursday we used to get fish and chips. Of course, you have to be in a place that sells food in batter to actually have that experience. But once you have it, it is a totally delicious experience, and it’s something that you will value wherever you are. It makes me think about how people describe some food as “street food” or “dirty food”—“dirty burgers,” for instance—the idea that food with working-class connotations is automatically dirty. It’s not dirty, it’s just bloody tasty.

And that’s what I love about Richard Hoggart’s book The Uses of Literacy. He writes so well about the importance of just having some of those treats available to you, just to make life sort of livable. If you’ve only ever known comfort, if you’ve only ever experienced a pretty smooth and navigable pathway through life, then appropriating deep-fried food and calling it “dirty” is just another way of somebody perverting the classless truth [laughs] of tasty food.

DF: I remember going into a shop in east London some years ago called Labour and Wait. It’s a homeware shop selling kitchen utensils and gardening implements. I saw a metal saucepan being sold for some astronomical sum, and it was exactly the same design, and made from the same materials, as one owned by my Welsh grandmother—my nain, as they say in Welsh. I remember that saucepan from Nain’s house in North Wales, and she owned it because it was practical and she couldn’t afford anything else. Seeing it kind of recast in the context of “authentic” postwar austerity aesthetics—1950s revivalist fetishism—was upsetting. It felt exploitative and insensitive. I know it sounds ridiculous to say that about a saucepan, but…

LH: No, there’s nothing wrong with getting upset about that. It actually gets to the heart of what I am trying to get at in the book.

DF: This over-valorization of “authenticity” is disturbing because it elides or covers up the much more complicated truths about, say, working-class culture that have often been concerned precisely with getting away from all of that stuff. Think about 1960s mod culture, for instance—that was born of wanting to look really good, wearing Italian suits. Or a band such as Spandau Ballet, who were working-class lads wearing ridiculous, voluminous jumpsuits and makeup and looking for a different experience of the world.

LH: There are two sides to “getting away,” though. In my first book I basically said that I grew up on a council estate and I didn’t like it and I couldn’t wait to get out. Saying that was in itself, potentially, a massive act of symbolic violence against the place I grew up in, the people I grew up with, and the people who live there now. So with this book I was desperate to recognize and put as much value as possible into the things that were good.

DF: Like a Greggs doughnut.

LH: Exactly.