Bullfight in a Divided Ring (detail), attributed to Goya. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1922.

When Ernest Hemingway shared with Max Eastman his guilt over ogling the girls in the dance halls of Paris, admitting that he always came home from his nights on Montmartre “disgusted with myself,” and asked Max if he felt so too, Max snapped back, “No, I don’t, Ernest. I enjoy lustful feelings, and what’s more I don’t think you’re talking real.” A sense of competitive masculinity, a question as to who was the better man and lover, had lurked in the background of Max’s relationship with Hemingway ever since they spent time together in Genoa. At the time, Hemingway was, in Max’s view, merely an “alert and vivid-minded journalist,” a well-mannered but otherwise unremarkable man with a fine set of teeth. Over the years, however, Hemingway had, unexpectedly, succeeded in what Max never accomplished: freed from the shackles of having to earn money as a hired hack, he had become an artist, someone who had succeeded in weaving his life experiences into his fiction. The tension Max felt whenever he read Hemingway erupted in a review he wrote of Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway’s account of the tradition of Spanish bullfighting, a book that challenged the genre of journalism by making the brutal ritual a cipher for Hemingway’s very personal search for meaning in life and nature.

“Bull in the Afternoon,” published in June 1933 in the New Republic, is one of Max’s masterpieces. Effortlessly, he mixes genuine admiration for Hemingway (his honesty, toughness, and, yes, courage, a “courage rarer than that of toreros”) with a scathing critique of his male posturing, his adolescent idealizing of violence. Max offered some of his best writing in a passage in which he imagined the suffering of the bull, “this beautiful creature…gorgeously equipped with power for wild life, trapped in a ring where his power is nothing.” And he poured his contempt on the bullfighters, “these spryer and more flexible monkeys,” who hunt the bull till he sinks down, “leadlike into his tracks, lacking the mere strength of muscle to lift his vast head, panting, gasping, gurgling, his mouth too little and the tiny black tongue hanging out too far to give him breath, and faint falsetto cries of anguish, altogether lost babylike now and not bull-like, coming out of him.” In a passage that would come to haunt Max later, he likened writing that derived pleasure from such senseless bloodshed—writing like Hemingway’s, in other words—to the “wearing of false hair on the chest.” To Papa Hemingway’s supporters this was blasphemy. “I don’t know when I have written anything that I have heard more about from various sources than that article,” sighed Max. Not bothering to read Max’s review carefully, Hemingway’s defenders engaged in the kind of public posturing and muscle flexing that ironically confirmed Max’s concerns. In a letter to the New Republic, for example, Archibald MacLeish rejected what he saw as Max’s psychoanalyzing of Hemingway—the suggestion that any ostentatious display of virility in literature must be caused by a lack thereof in life—as “scurrilous” and attested to having seen Hemingway behave courageously “once at sea, once in the mountains, and once on a Spanish street.” Hemingway chimed in from Cuba and challenged Max to put his speculations in writing: “Here they would be read (aloud) with much enjoyment (our amusements are simple).” In response, Max emphatically denied he had ever implied Hemingway was impotent, “although I have long been familiar with the news that I am—and gymnastic enough to be syphilitic at the same time,” and reminisced about the time he had first laid eyes on him: “He had just been blown out of a bathroom by an exploding gas-heater” and “arrived halfway down the hall with a smile on his face like a man on a toboggan.” Somewhat less helpfully, Max, in his personal note of apology to Hemingway, reiterated his criticism: “I suppose it is fresh to psychoanalyze a man by way of literary criticism, especially one whom you esteem as a friend, but I think there is plenty of cruelty in the world without your helping it along.” Hemingway never forgave him.

The following year Max included the review in his collection Art and the Life of Action. The book received generally positive reviews.

The most forceful response to the book came three years later. On August 17, 1937, Max was visiting his editor Maxwell Perkins’ office, discussing a new edition of Enjoyment of Poetry, when Hemingway sauntered in. He was not in a particularly generous mood: his marriage with Pauline Pfeiffer was on the rocks, and he was about to return to Spain, where the civil war he had been covering had reinforced his contempt for literary refinement. Opening his shirt, he encouraged Max to assess the authenticity of his chest hair, while he mocked Max’s chest, which was, remarked Perkins, as “bare as a bald man’s head.” Then everything went haywire. Seeing the well-fed, white-clad, good-looking Max, tanned from tennis and hours spent napping on the beach, Hemingway erupted. The way Max remembered it, Hemingway was crude and aggressive. “What did you say I was sexually impotent for?” he snarled. Conveniently, a copy of Art and the Life of Action was sitting on Perkins’ desk. Max attempted to point out a passage—a positive one, we might imagine—that he thought would clarify that he had never wanted to trash Hemingway. But Hemingway, muttering and swearing, zeroed in on a different passage, and a particularly good one it was, too: “Some circumstance seems to have laid upon Hemingway a continual sense of the obligation to put forth evidences of red-blooded masculinity.” This was Max at his best, the use of the plural “evidences” giving the line a rhythmic lilt: “évi / dénces of / réd-blooded/ máscu / línity.” An altercation ensued, during which Max, as both parties agreed, got “socked” on the nose with his own book. Everything was happening very fast after that. Max charged at Hemingway. Books and other stuff from Perkins’ desk went flying to the ground. Convinced that the much younger Hemingway was going to kill his friend, Perkins rushed in to help. By the time he had reached the two men they were both on the floor. Max was on top, although Perkins felt this was by accident only. But Max would later tell everyone who cared to listen that he had been the winner. Recognizing the disadvantage imposed on him by age and lack of physical fitness (“I would have kissed the carpet in a fistfight with Ernest Hemingway”), he claimed he had used a wrestling move to throw Hemingway on his back over Max Perkins’ desk. Hemingway assured the Times no such thing had taken place, that Max instead had taken his slap “like a woman.” He went on to challenge Max to meet him in a locked room and read to him his review in there, with “all legal rights waived”—the Hemingway equivalent to challenging his adversary to a duel. There is one detail, however, that does make Max’s account credible: he did know how to wrestle.

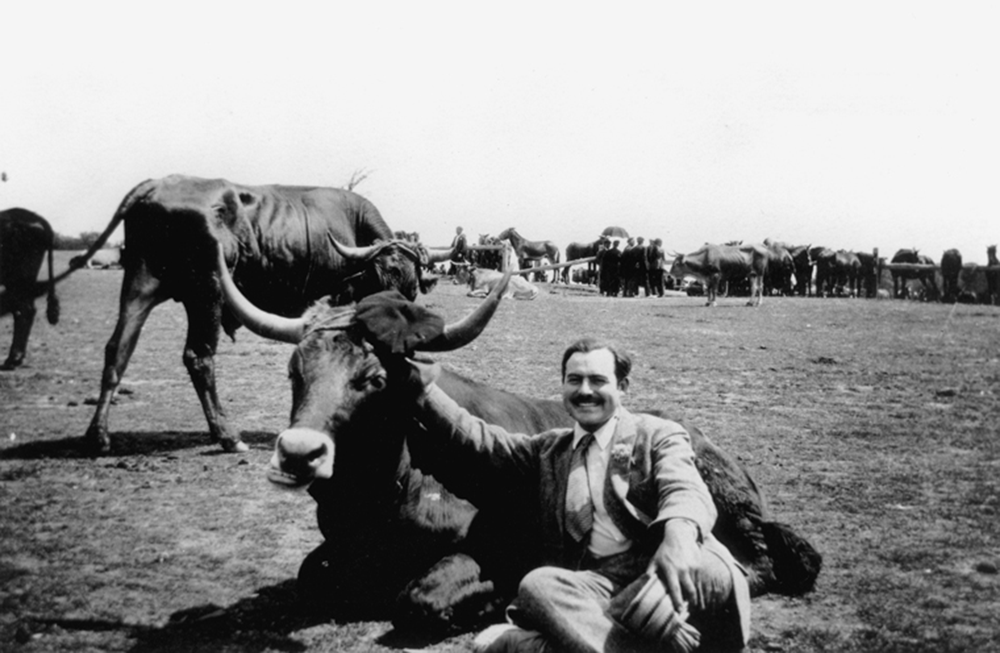

The literary “battle of the ages” was widely covered in the papers. The Herald Tribune noted that while Max was older, both he and Hemingway were in the “heavyweight category.” That said, Max would have been pleased to see he was trimmer than his younger antagonist:

Hemingway

Age: 39

Height: 6 feet

Weight: 197 pounds

Eastman

Age: 54

Height: 6 feet

Weight: 180 pounds

The accounts of the fight differ, but there is independent confirmation of one other detail: the book Hemingway used, now kept at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, which features, on the flyleaf, a clumsy drawing of a paw with the resonantly poetic inscription, “This is the book I ruined on Max (the Prick) Eastman’s nose, I severely hope that he rots forever in a hell of his own digging. Ernest Hemingway.” It seems Hem had nicked the book from Perkins’ office. His besmirched masculinity (when he talked to the Times he sported a bruise on his forehead that he claimed had not been caused by Max) required that he document his accomplishment for posterity.

Max’s friends and supporters rallied to his defense. In a telegram to him a group of ladies, the Ladies of Kings Beach on the Vineyard, felt the need to reassure Max that “you have got hair on your chest.” Edna St. Vincent Millay and Eugen Boissevain told him he had seemed “dignified and lovely” throughout the entire unpleasant episode. Some less generous observers thought the Hemingway–Eastman scuffle was a mere publicity stunt, hyped by Max to counteract his declining relevance in a changing world. One thing is sure: Max “the Prick” had gotten his point across. In September, the New Yorker ran a cartoon showing a rather unhappy-looking man at a physical being diagnosed as a writer merely because of the fluff on his chest.

In the decades that followed, Max almost obsessively revisited the scene, seeking reassurances from others who had seen or heard what had happened—men who were now old, like Max, too—that Hemingway had not had the upper hand in their scuffle. What was at stake was more than literary criticism or Max’s right to say what he wanted about a fellow writer. As Hemingway went from one well-publicized risky adventure to the next, Max continued to insist on his own version of masculinity that involved not loud displays of virility but a deliberate celebration of the human body and its infinite capacity for pleasure.

As it turned out, Max was not the only one with a grudge against Hem. Decades after the battle in Perkins’ office a mutual friend of the two men, the painter Waldo Peirce, presented Max with a surprise gift. In the 1920s Peirce had been Hemingway’s fishing buddy in Florida, and on one of those occasions Peirce persuaded Hemingway to pose for his camera wearing nothing but a kind of turtle shell or sponge on his head and the butt-rest of a fishing rod covering his privates. Waldo, despite his rough exterior, was a devoted family man, a “domesticated…cow,” as Hemingway unkindly called him in a letter to John Dos Passos, and it’s possible Peirce saw sharing the photograph with Max as an opportunity to get back at Hem. He inscribed it on the back: “The great Pescador hiding his light under a but[sic]-rest.” When he got the picture, Max, with evident satisfaction, noted the near absence of chest fur. And he published it in the second volume of his autobiography, accompanied by the sarcastic caption, “Hemingway in the twenties.” By then Hemingway had been dead for three years.

Whether Max or his publisher balked, we don’t know. But in the published version of the photograph Hem is wearing a pair of dainty swimming trunks. No matter, Max had finally won the battle.

A trip to Cuba in early 1946 brought Max face-to-face with his nemesis Hemingway again; neither had been spared by the ravages of time. Max and his wife Eliena had run into him by accident at the Bar Florida in Havana, where the Eastmans had gone to cash a check and had stuck around watching the delicate-handed barkeeper mix daiquiris. “Hello, Ernest,” Max said when he recognized Hemingway and extended his hand. But he also quickly calculated what he would do if Hemingway decided to hit him: “He’s in a perfect position to be tackled and thrown through the door on the sidewalk.” Hemingway did not do him the favor: “Hello, Max,” he responded quietly. The two men talked, cordially, and when Eliena joined them, Max said, as if they were at a cocktail party and nothing had ever happened between them, “You remember Eliena, Ernest?” Eliena couldn’t believe this fussy, “top-heavy,” soft-spoken man with eyes as brown and expressionless as a beetle’s peering at her through small steel-rimmed glasses was the same “blood-lusty he-man” she had known in Paris. He looked like an overweight English professor on vacation; when someone tried to take his picture Papa fumbled with his glasses, took them off, and then smiled: “Now I look more like I used to.”

Adapted from Max Eastman: A Life by Christoph Irmscher. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.