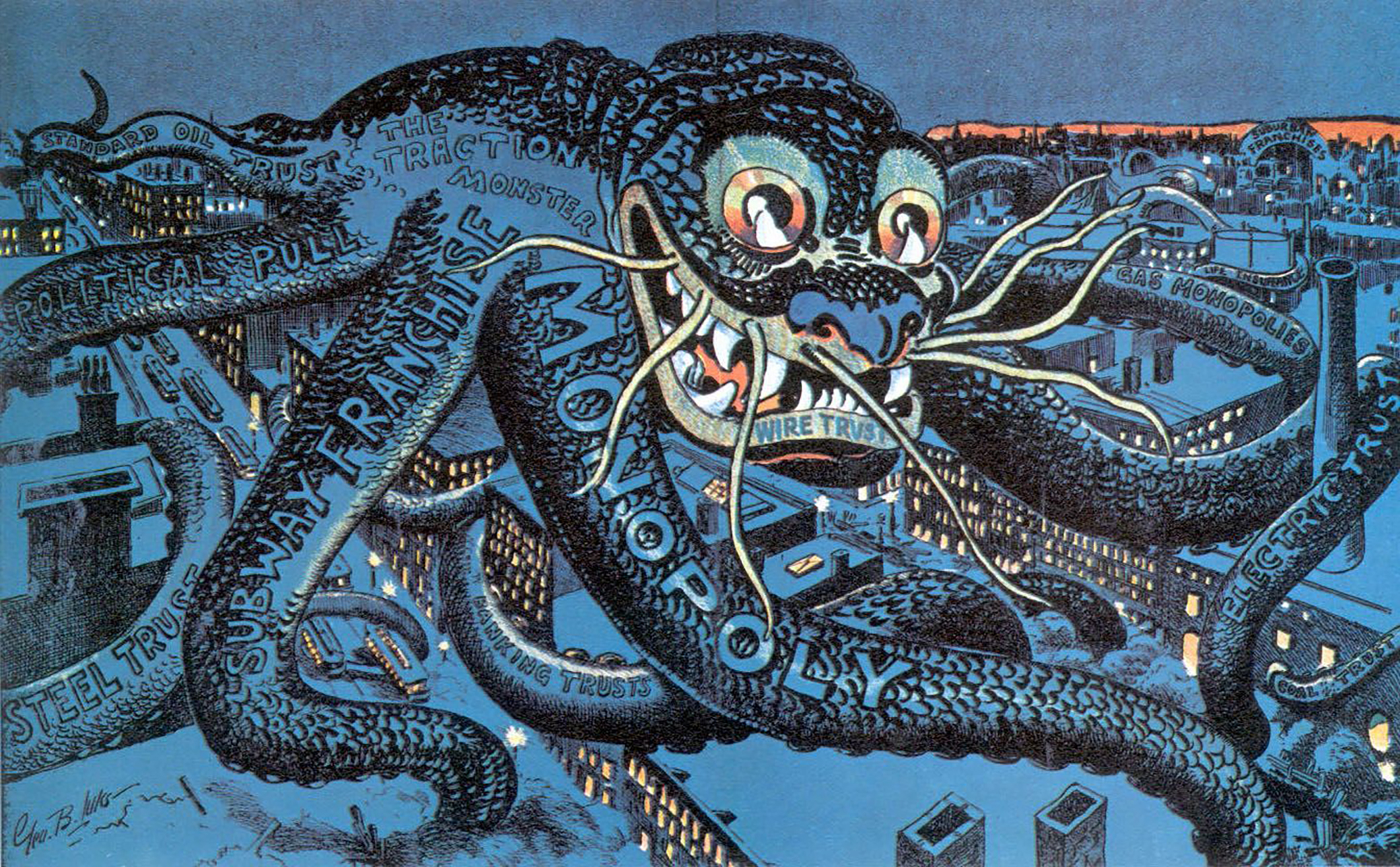

The Menace of the Hour, by George Luks, 1899. Wikimedia Commons.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.

When asked to name the American novel with the greatest continuing social relevance, the literary historian is apt to reply with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the top-selling book of the nineteenth century after the Bible. Scholars credit Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel with broadening abolitionist sentiment in the late antebellum period and with helping to create the divided and resolute mind-sets required for the nation to split over the question of slave labor.

But Uncle Tom’s Cabin has less to teach us about politics in today’s America than does another novel that appeared almost forty years later.

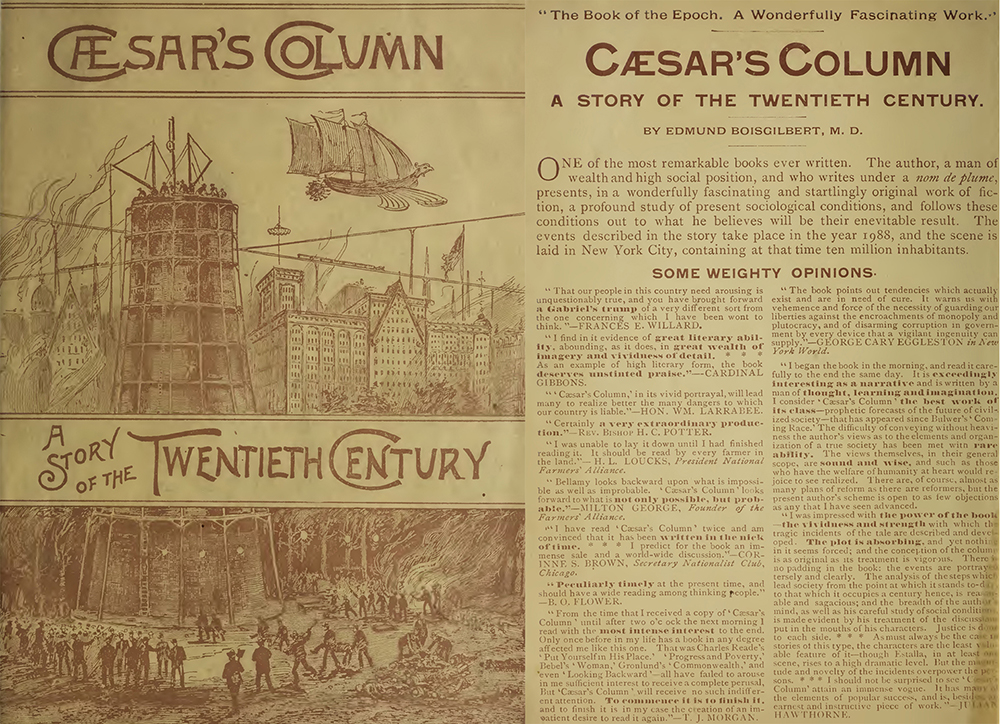

Published under the pseudonym Edmund Boisgilbert, MD, Caesar’s Column: A Story of the Twentieth Century (1890) sold hundreds of thousands of copies in the final decade of the nineteenth century. Despite the author’s belief that his novel was the rightful successor to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it never entered the canon of high school and college curricula; today its readership is largely restricted to enthusiasts of late nineteenth-century culture. Yet perhaps more than any other novel published in the United States, Caesar’s Column illuminates the origins of the present crisis in American race relations unfolding under the banner of a resurgent populist nationalism. Although Madison Grant’s eugenicist tract The Passing of the Great Race (1916) is often cited by twenty-first-century journalists as the urtext of modern American white supremacy, it merely applied the new science of statistics and a welter of demographic data to a narrative that Caesar’s Column had sensationalized a quarter century prior. The novel popularized the paranoid “great replacement” theory that troubled Grant—and now animates twenty-first-century white nationalist movements in the United States and Europe.

Caesar’s Column hit shelves at the peak of the Gilded Age. As a result of the backroom compromises that produced the electoral college victory of President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, the Republican Party had already shifted investments of its political capital from Reconstruction to big business. Industrialists and financiers gained unprecedented political and economic power throughout the following decades, and socioeconomic inequality rose to obscene new heights, provoking deadly clashes between organized labor and the hired hands of industrial capitalists. By 1890 the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Haymarket Affair of 1886 had set the country on edge by exposing the violence required to repress the demands of the working classes. Religious leaders, liberal journalists, and many of those who remained only tenuously in the middle classes feared that the next contentious strike could lead to a wide-ranging insurrection resulting in martial law or mob rule. This dark scenario is brought to life in Caesar’s Column.

Set in 1988, the novel purported to offer a prophetic glimpse into America’s terrifying future, depicting a country where democracy has been corrupted into an oligarchy controlled by the great “Rings” of industrial monopolies. The novel’s protagonist, Gabriel Weltstein, is a Jewish colonist from Uganda who comes to New York with the vain hope of selling his wool directly to the city’s manufacturers, thereby circumventing the despotic Wool Ring, “which has not only our country but the whole world in its grasp.” In America he discovers the folly of his aspiration: the entire country is ruled by a league of monopolists who have the textile manufacturers “tied with hand and foot…It is a shameful state of affairs in a country which calls itself free.”

Such a state of affairs did not require much imagination for readers in 1890 to picture; the novel was pitched to the members of an ascending populist coalition that emerged to oppose the Gilded Age’s great monopolies. This political uprising had its roots in the rural heartland, where small farmers saw themselves as victims of extortion by eastern financiers who blocked the monetary policy reform that could have alleviated their debts, and by railroad tycoons who drove them further into the red with their price-fixing schemes. Organized politically as the Greenback and Anti-Monopoly parties and in fraternal organizations like the Grange—an alliance of Midwestern farmers and laborers fighting against rate discrimination and other monopolistic practices of the eastern railroad companies—this coalition would eventually cohere in 1892 as the People’s Party (also known as the Populist Party), just two years after the publication of Caesar’s Column.

Having succeeded in capturing the electoral and legislative processes, the monopolist cartels depicted in Caesar’s Column effectively control all three branches of U.S. government. The wealth they hoard generates astonishing inventions—airships, air-conditioning, flat-screen monitors, and wearable technology are among the many modern contrivances the novel correctly predicts—but leaves millions of poor workers mired in the misery of industrial city slums. The largely immigrant workforce procreates with abandon, causing the degeneration of the nation’s genetic stock as the overpopulated slums begin to select for strength and cunning over charity and reason. Darwinian evolution quickly reverses the great strides of Western civilization, devolving the masses into an illiterate horde of hypersexualized brutes with a natural predisposition to violence and domination. These nearly subhuman oafs make for hardy factory laborers but require constant subjugation by the hired thugs of the monopolists, lest they wreak the havoc of the slums upon “civilized” sectors of society.

The workers’ coarsened human nature, combined with burning resentments over their exploitation and squalid living conditions, eventually explode into a conflagration that topples the “civilized” society established and maintained by the Rings. As the result of a surprisingly well-coordinated insurrection planned by a secret worldwide trade union known as the Brotherhood of Destruction, the United States and much of Europe are reduced to smoldering ruins while Weltstein and a Brotherhood confrere named Max flee the continent in blimps, escaping to Weltstein’s colonial settlement deep in the mountains of Uganda along with the sweethearts they’ve married during a brief romantic interlude in the narrative. Back in New York, the Brotherhood of Destruction claims victory, but civilization is already slipping back into the barbaric anarchy of warring clans. So much, the story appears to conclude, for American exceptionalism.

Caesar’s Column was a polemical sensation when it was published on April Fool’s Day in 1890. The novel sold sixty thousand copies in the months following its initial release, with sales reaching more than a quarter of a million copies over the course of several editions in the United States and England, as well as translations into German, Swedish, and Norwegian. The dystopian narrative was revealed that November to be the handiwork of political chameleon Ignatius Donnelly, a former lieutenant governor and three-term Radical Republican congressman from Minnesota (serving from 1863 to 1869) whose perpetual candidacies and campaigns made him a fixture of state politics.

Donnelly had already cultivated a reputation of considerable notoriety by the time Caesar’s Column was published. He had moved to Minnesota from his native Pennsylvania to establish a model town called Nininger, which he hoped would be settled by immigrants shepherded to America by an aid society to which he belonged in Philadelphia. After the project faltered within a few years, Donnelly was elected to Congress, where he distinguished himself as a reformer and friend to the railroad industry, which he viewed as crucial to the development of the western states. He voted to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, and advocated for the political and economic equality of freed slaves. He also launched an investigation into the federal government’s treatment of American Indians. And he sponsored a bill to establish a national bureau meant to encourage immigration by protecting and supporting those who arrived from abroad.

After losing his bid to be reelected to a fourth term in Congress in 1868, Donnelly ran and lost again in 1870, this time as an independent endorsed by the Democrats. Ever the pragmatic changeling, Donnelly reinvented himself first as a railroad lobbyist, then as the Washington correspondent for the St. Louis Dispatch. In a reversal inspired by his insider’s view of the railroad business and his intimate acquaintance with the ways it had corrupted elected officials, he returned to the Midwest as a spokesman and lecturer for the Grange, and continued working on behalf of central and northern European immigrants in Minnesota. Involvement with the Grangers led Donnelly to become a propagandist for the Anti-Monopoly Party, a third party he helped establish in 1874 to organize populist opposition to the railroad monopolies. The Anti-Monopolists advocated numerous causes later championed by the Greenback and Populist parties, such as the adoption of fiat currency, the direct election of senators, expanded labor-union rights, and the enactment of antitrust legislation.

Although Donnelly seemed to adopt and abandon certain populist causes as they came into and went out of fashion, no one ever doubted his radical bona fides. This was particularly true when it came to his defiant proclamations regarding the corrosive influence of monopoly capitalism at a time when both major parties endeavored to win the favors of big business. Relentless activism propelled Donnelly back into elected office in the Minnesota state senate, where his 1874–78 term was largely characterized by a crusade against monopolistic “combinations.” Speaking at the Greenback National Convention in 1876, he became one of the first American political leaders to call for the creation of a People’s Party.

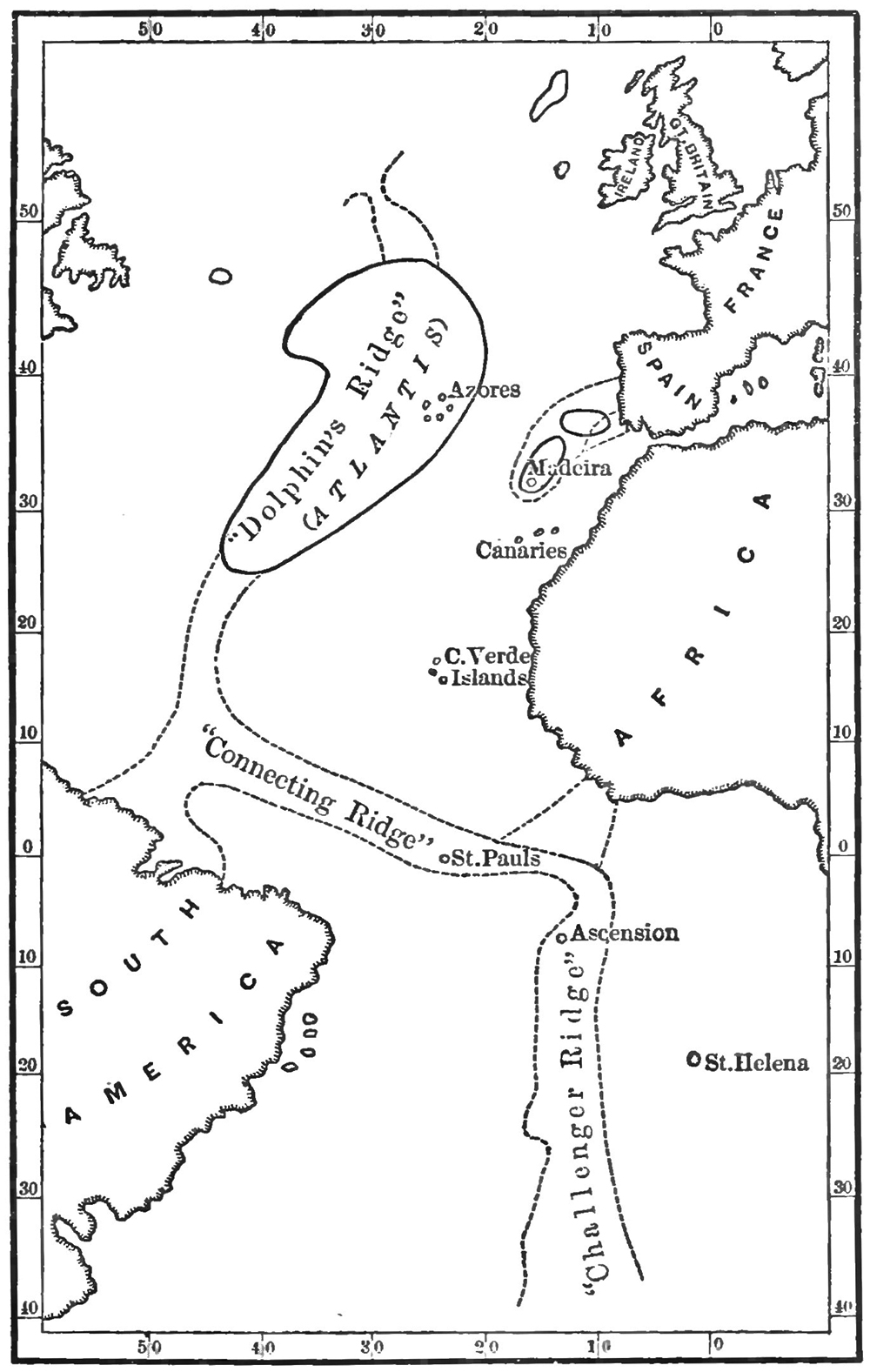

It was not until the next decade that Donnelly, out of office once more, finally found his true métier as a best-selling author. His 1882 book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World was responsible for popularizing the modern myth of the lost continent. It made Donnelly famous and went through more than twenty editions in the United States and England. Fan mail came pouring in, including a letter from British prime minister W.E. Gladstone. Donnelly’s rapid follow-up to Atlantis was Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel (1883). Written in just seven weeks, this “scientific” text offered an alternative geological history of the earth’s formation. Initial sales were brisk, but the book failed to live up to expectations set by Atlantis.

Meanwhile, the author had used some of his royalty earnings to buy a facsimile edition of Shakespeare’s first folio, in order to research the next chapter in his rapidly forming canon of factually challenged exposés. In 1887 Donnelly attempted to prove the fringe theory that Francis Bacon had written the works commonly attributed to William Shakespeare in an essay titled “The Shakespeare Myth.” The article generated a $6,500 advance (approximately $180,000 in today’s currency) for Donnelly’s book The Great Cryptogram, in which he claimed to have discovered a cipher that Bacon had hidden in Shakespeare’s historical plays. The book was a commercial failure, and was dogged by criticism from Shakespeare scholars. After that humiliation, Donnelly published Caesar’s Column under a pseudonym, revealing his identity only after the novel had become a resounding triumph.

Although it still trafficked in conspiracy theories, Caesar’s Column was a shrewd and calculated return to Donnelly’s populist concerns. The novel was aimed at recruiting the crucial urban labor constituency into a burgeoning populist revolt against the monopolistic interests that increasingly set the policy agendas for both major political parties. It dramatized, in sensational fashion, several postbellum anxieties that had matured into Gilded Age obsessions. Chief among these was the fear that “the race”—usually understood to be restricted to a socially constructed Anglo-Saxon identity—was in danger of degenerating or devolving as a consequence of extreme social inequality and the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor in Northern urban slums, where liquor and Catholic intemperance combined with machine politics, child labor, and crowded, unsanitary living conditions.

Race suicide, the popular term to describe this phenomenon, would not be coined until 1901, when the sociologist and eugenicist Edward Alsworth Ross used the phrase in his article “The Causes of Race Superiority.” But the concepts behind Ross’ term had rapidly evolved (so to speak) during the decade since the publication of Donnelly’s novel. Ross’ thesis was a culmination of the ideas that paved the way for later Progressive Era endeavors in eugenics and immigration restriction: two related concerns that many Progressives believed were allied with the democratic crusade for social reform they had inherited from late nineteenth-century Populists after the People’s Party collapsed in the wake of its defeats in the elections of 1896.

As the historian Beryl Satter has written of the 1890s in her book Each Mind a Kingdom: American Women, Sexual Purity, and the New Thought Movement, 1875–1920, a desire to bring about the perfection of “the race” characterized an emergent political discourse she calls “evolutionary republicanism,” associated with reformers such as Benjamin O. Flower and visible in the work of cartoonist Thomas Nast, among others. A complement to social Darwinism, this school of “reform Darwinism” held that active measures to ensure the progressive evolution of the population were the patriotic duty of the nation’s fortunate and enlightened citizens. What made Anglo-Saxon society so desirable and successful, these reformers believed, were its socially enforced inclinations toward sobriety, restraint, and economy. These were qualities that could and should be cultivated in new Americans as part of the assimilation process—provided that immigrants were not viewed merely as a source of cheap, powerless, and disposable labor. Where social Darwinists believed that only the harsh realities of market capitalism could ensure the natural selection needed for a strong and healthy society, reform Darwinists believed that monopolists had created artificial conditions for the literal devolution of the species by disregarding the negative social consequences of laissez-faire capitalism. Many late nineteenth-century reformers feared that if left unchecked, industrial exploitation of the urban working classes, which were increasingly comprised of cheap immigrant labor, would ultimately result in a social degeneration that would spell the end of Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism. Following the turn of the century, similar concerns and ambitions led Progressive Party reformers down the disastrous detour of “scientific” eugenics.

In the opening pages of Caesar’s Column, Donnelly made it clear to which camp he belonged. Arriving in New York, the novel’s protagonist checks into a luxury hotel called the Darwin, whose fantastic comforts and technologies amaze him nearly as much as the miseries of New York’s slums will later appall him.

Today the outlines of evolutionary republicanism resurface in the rhetoric of white nationalists who oppose all but the most selective immigration policies. New terms have once again displaced the old and in the process have warped the progressive, albeit assimilationist, aims of evolutionary republicans like Donnelly into their inverse: a nativist, exclusionary, and reactionary variant of the same theory. A terminological sleight of hand signals this transformation: rather than warn against potential “race suicide” resulting from the social ills that proceed from a surrender to market forces, contemporary white supremacists decry a liberal plot to commit “white genocide.”

More than just the modern argot for race suicide, white genocide is a term devised by far-right activists and pundits to describe an alleged leftist conspiracy to make white Americans a demographic minority, and then to use the democratic process, or mere strength in numbers, to advance an anti-American political agenda that requires the subjugation of the white race and everything it supposedly stands for. This shift from self-inflicted harm to malicious homicidal intent corresponds to a broader adjustment in white nationalist discourse: the conscious adoption of victimhood status. Radical variants of the prophecy warn that nonwhite populations plan the eventual extermination of the white race, either through violent means or through simple arithmetic, citing the increased rates of interracial marriage and mixed-race offspring that they believe are likely to result from liberal immigration policies. Similarly, nativists selectively cite birth-rate statistics to support their claims that immigrants tend to have more children than native-born Americans. White nationalists caution that unless these demographic trends are vigorously opposed, they will doom Anglo-Saxon America to inexorable demographic decline and eventual extinction. This is the same “great replacement” narrative pushed by late Victorian evolutionary republicans, now purged of its concern for housing justice, human welfare, and labor reform and distilled instead to pure xenophobia.

The white-genocide conspiracy theory manifested during the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, with white nationalists chanting, “You will not replace us.” An alternate rhyming chant, “Jews will not replace us,” indexed another consistent element of conspiratorial white-supremacist discourse: the conviction that Jews have masterminded the great replacement for their own nefarious ends. Adopting the pose of victims once more, white nationalists frame demographic changes in the United States as the result of an international Jewish conspiracy.

Although it was initially confined to fringe far-right groups and white nationalist websites like the Daily Stormer, “white genocide” has become such a familiar trope in far-right circles that Fox News commentators have begun to echo elements of the conspiracy theory in their broadcasts. QAnon, an online community of anonymous conspiracy theorists who believe they are unraveling a worldwide network of child sex exploitation, usury, assassination, and propagandistic social control, has also taken up the “great replacement” narrative. General consensus among the Anons is that the Central American migrant caravan of 2018 was a publicity stunt orchestrated by the Jewish financier George Soros, an American citizen who emigrated from Hungary; they allege Soros hoped the caravan would cultivate sympathy for Latin American immigration to the United States and result in a PR disaster that would halt the Trump administration’s efforts to tighten immigration controls.

Adherents to the “great replacement” theory also ascended to positions of power and influence in the Trump administration. These include Stephen Miller, who since 2017 has been a policy adviser in the Trump White House, overseeing the administration’s controversial changes to immigration policy. Emails leaked in 2019 by former Breitbart editor Katie McHugh show that in July 2015, while still serving as an aide to Alabama senator Jeff Sessions, Miller sent Breitbart staffers links promulgating the “white genocide” and “great replacement” narratives. One of the books Miller recommended in his emails to the Breitbart team was Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints, a 1973 French novel that depicts a dystopian future in which France has been overrun by nonwhite immigrants who fail to assimilate.

The Camp of the Saints has inspired dozens of anxious essays in liberal American publications, fretting over the book’s popularity in white-supremacist circles. Likewise, Madison Grant has become the whipping boy of liberal journalists endeavoring to dig out the roots of modern American white supremacy and nativist fervor. Seldom, if ever, does the name Ignatius Donnelly appear to merit mention in these hand-wringing analyses of reactionary populism, even though Caesar’s Column relied on similar themes. This may be because Donnelly was a different sort of populist than the reactionaries who crowd into Donald Trump’s rallies: born in Philadelphia to an Irish immigrant father and second-generation Irish American mother, Donnelly spent his early years working for various immigrant-aid societies, and used the latter half of his career to crusade against tycoons whose corporations exploited immigrant labor. He and other evolutionary republicans saw the misery in which immigrants to Gilded Age America were forced to live as a threat both to democracy and to ennobling human development, whereas contemporary white nationalist republicans blame demographic change for any number of undesirable cultural problems.

Despite the tremendous success of Caesar’s Column, and the novel’s role in entrenching the great-replacement narrative in left- and now right-wing populist discourse, Donnelly and his work are largely forgotten. Although the novel found hundreds of thousands of buyers and may have entertained millions of readers, its evolutionary republican message was too easily misread as nativist alarm by Populists and leftists who, like Edward Alsworth Ross, were already inclined to scapegoat immigrants: why aid the powerless when they can be made to take the blame? Because this line of thinking transcended other political divisions, it insulated powerful corporations—the ultimate beneficiary of racist divisions among the working class—from the concentrated wrath of a consolidated urban–rural populist alliance. Donnelly’s narrative stratagem had dangerously backfired.

The obliteration of Caesar’s Column from the canon is also due, in part, to twentieth-century critical evaluations of the novel as intolerably racist. Caesar’s Column contained racist stereotypes and anti-Semitic tropes that confused its progressive, anti-corporate, pro-worker, pro-immigrant message. The Brotherhood of Destruction is led by a crafty Jew and the mixed-race Caesar Lomellini, who builds a monument in New York City’s Union Square with the bodies of dead oligarchs, entombing the stack of human remains in a tower of concrete: a warning to future generations that becomes known as Caesar’s Column. Like the People’s Party that overtook the Grange and Anti-Monopoly movements, Donnelly embodied one of the signature contradictions of the era: a progressive populism that yoked racist paternalism to its defense of workers’ rights and a Jewish conspiracy theory to its opposition of corporate “money power.”

Decried as dangerous anarchist propaganda by its contemporaries and ejected from the canon for relying on racist stereotypes, Caesar’s Column should not escape the attention of historians endeavoring to understand the origins of the present crisis. The novel laid the groundwork for the paranoid fixation on cultural dilution and genetic pollution that continues to bedevil the United States.