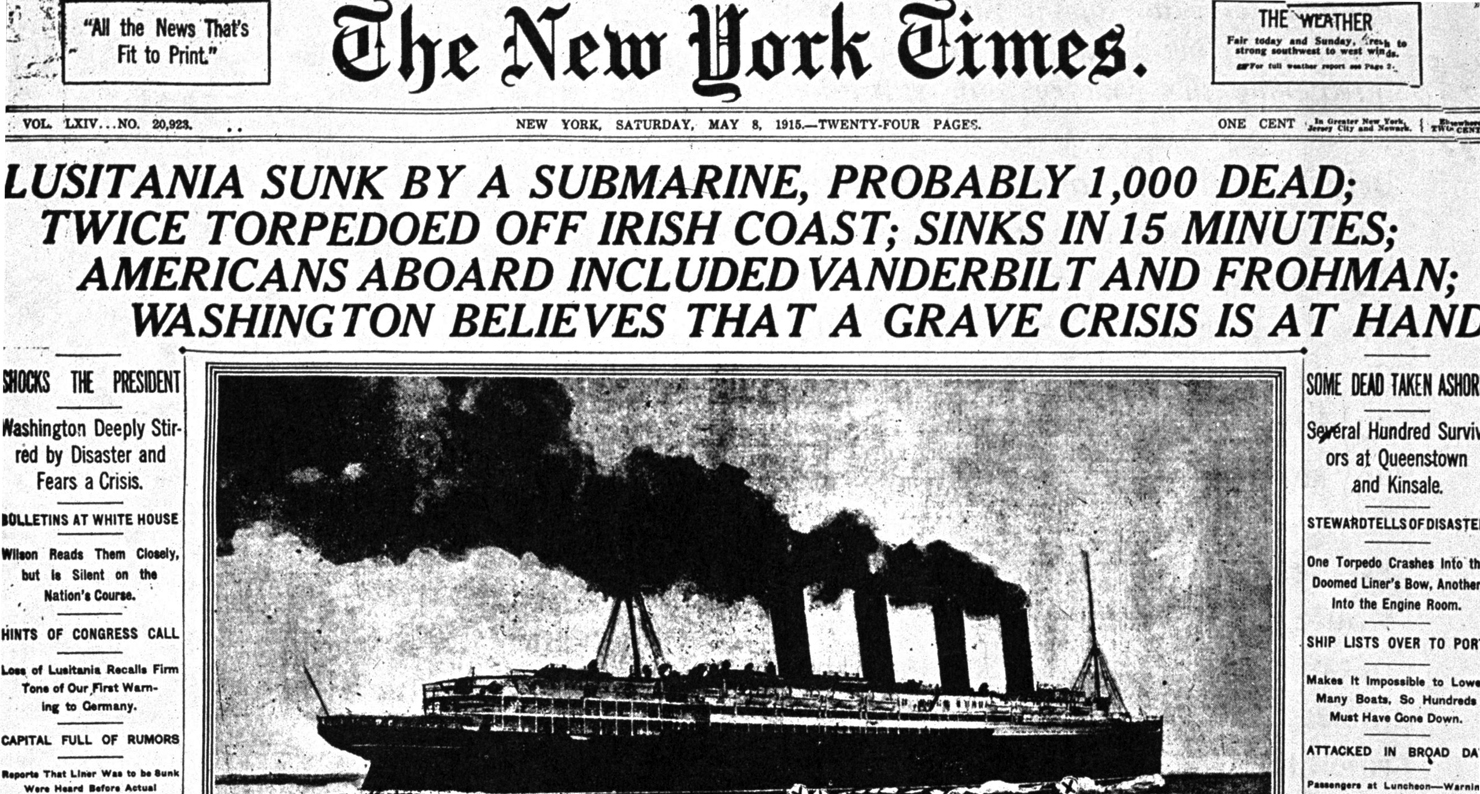

The front page of the New York Times, May 8, 1915.

The morning of Friday, May 7, 1915 was still and foggy off the coast of Ireland. The weather was getting warmer, and the anticipation of the first spring and full summer of the Great War would change the weapons strategy for both Germany and the Allies on land and at sea. The opposing armies in Belgium and northern France were dug deep into parallel trenches, a stalemate that would come to define the war. In late April, the Germans had fired more than 150 tons of chlorine gas across the lines to force the enemy into retreat. In dry conditions, with the wind in the right direction, the effects of gas could be devastating. And in the seas around Great Britain, the lurking German submarine fleet was becoming more practiced and more audacious in its targets.

The fog was still dense as the massive RMS Lusitania ocean liner, the jewel of Britain’s Cunard fleet, approached the coast of Ireland on its way to Liverpool. The U-boat captain who had the ship in his sights couldn’t see in the foggy conditions and turned for home. But as the morning wore on, the fog lifted, and the sky grew clear and bright. He could now see and be seen, so he stayed below the surface—just low enough that at 11:50 a.m.. a large British warship passed directly overhead, moving too fast for him to catch. Ships were ordered to zigzag at top speed through these dangerous waters to try to elude the lumbering submarines. The technology was not sophisticated enough to chase the heat of a passing target, it was a matter of eyesight, radio interception, and luck. Just two hours after his frustrating near miss, the U-boat captain, Walther Schwieger, got absurdly lucky. Around 2 p.m., he spotted the Lusitania’s distinctive four funnels and fired off a torpedo. People on deck could see it rushing toward them, a twenty-foot missile racing through the clear water, too late and too fast and too shocking to dodge.

As is meticulously detailed in Dead Wake, Erik Larson’s recent bestseller about the Lusitania’s sinking, the passengers aboard the liner were well aware of the risks of sailing through British waters, as were the American and British governments. The German government had declared the area a war zone, and announced they would not hesitate to attack even neutral ships. President Woodrow Wilson declared that any German attack on American civilians would be taken seriously. He did not spell out the consequences, but the threat of American entry into the war was obvious. Americans sailed to Britain at their own risk, although the Cunard Line claimed that the Lusitania’s speed, size, and maneuverability made her as safe as it was possible to be. But even the most modern luxury liner could not survive a direct hit to its hull. Two huge explosions—the torpedo’s impact and another blast, probably a ruptured steam line—sank the ship within minutes, killing 1,195 people, including 123 Americans. On May 10, the Irish coroner of the district where five of the dead had come ashore declared that the Kaiser and his submarine officers were guilty of “willful and wholesale murder.”

Why didn’t the sinking of the Lusitania propel the U.S. more quickly into war? It would be two years before the first armed American destroyers sailed for Europe, and there was no shortage of pro-war activism in the American press. Britain and Germany were not strange and distant lands, and their citizens were not strange and foreign people. They were the homelands and the ancestors of the American ruling class.

Why, too, did Britain not do more to capitalize politically on the tragedy, instead seeking to blame the ship’s captain for negligence? After all, it was in British interests to goad the U.S. into war. Looking back, Winston Churchill, first lord of the Admiralty, was convinced this American hesitation had prolonged the war. He wrote in his memoir that if the sinking of the Lusitania had brought the U.S. into the war in 1915, “what sparing of agony, what ruin, what catastrophes would have been prevented!” But this was hindsight. At the time, the British had their own asset to protect—Room Forty, the secret decoding lab within the Admiralty. The Room was a precursor to Bletchley Park that intercepted and translated messages about German U-boat activity. Agents in the lab knew with remarkable accuracy where U-20, the sub that attacked the Lusitania, was moving and what it was planning. After the files relating to Room Forty were declassified in the 1970s, a conspiracy theory took hold among naval historians that the British had deliberately let the Lusitania glide into harm’s way in the hope of forcing Wilson’s hand. When that strategy failed, it was imperative that the whole thing look like a tragic mistake.

Attacks that precipitate military action of course invite conspiracy theories. But President Wilson seems to have gone out of his way to avoid the implication that the U.S. could be forced into war by the emotions roused by an attack on its civilians. He was criticized in the press in the days that followed the sinking for appearing cold and detached. His overt response, ripe for popular parody, was to issue Germany with a series of “notes” throughout 1915, which began by urging Germany to stop attacking merchant ships. He did not, however, warn Americans to stop traveling to Europe. In early June, after further attacks on other civilian ships and more American losses—although nothing on the scale of the Lusitania—the President took the moral high ground and appealed to the Germans to share it.

The government of the United States is contending for something much greater than mere rights of property or privileges of commerce. It is contending for nothing less high and sacred than the rights of humanity, which every government honors itself in respecting and which no government is justified in resigning on behalf of those under its care and authority.

And in July, still urging Germany to respect fundamental human rights, Wilson declared that any further attacks on merchant ships would be regarded as “deliberately unfriendly.” But he stopped well short of suggesting that such “unfriendliness” would be met with force.

With the pro-war factions in the U.S. becoming more impatient—notorious hawk Teddy Roosevelt wrote a friend in the summer of 1915 that he was “pretty well disgusted with our government and with the way our people acquiesce”—the wrangling continued, and Wilson was reelected in 1916. In December, the president was still hoping to keep the U.S. neutral, encouraged by Germany’s claims that it had made overtures of peace to Britain, which the British had rejected. Yet at the same time, the German government was itself divided. Even the Kaiser had his doubts about the morality of submarines’ attacking ships that carried civilians, especially women and children, and it was not in his interest to provoke the Americans. But several high-ranking politicians, bolstered by the public’s faith in this magical naval weapon, were pushing to lift the remaining restrictions on submarine warfare, making any vessel fair game. By 1917 Germany had over 100 U-boats prowling the seas, more than three times the number it had when the Lusitania was attacked.

The pro-submarine faction won. On January 31, 1917—the day before the no-holds-barred campaign was to begin—the German ambassador announced the new policy to Wilson. The British, who had intercepted the message from Germany some days before, waited anxiously to see if this new threat would by itself be enough to prompt American entry into the war. By now, in the wake of unimaginable losses in the Battle of the Somme—a months-long fight that had daily set new, horrifying standards for what losses the nation could bear—American military assistance was a matter of urgency. So there was jubilation in Room Forty when another message from Germany was intercepted in February. This message seemed to threaten the last vestiges of American isolationist policy.

On February 24, the British presented the American ambassador with what came to be known as the “Zimmermann telegram.” This flimsy document suddenly threatened to bring the distant war right up to the American border. Purportedly sent by Arthur Zimmermann, the German foreign secretary, the telegram offered the government of Mexico a tempting prize for entering the war on the German side: the restoration of land it had lost to the U.S. in New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona. The Mexicans, embroiled in their own revolution, ignored it. The British held their breath. They had already sat on the message for a few days, in order to give credence to the idea that they had obtained the message directly from a spy in the Mexican telegraph office, rather from the secret Room Forty. During that time, the relentless German U-boat campaign continued, and another Cunard passenger liner, the Laconia, was sunk off the oast of Ireland, killing two American women. But the Admiralty’s greatest fear was that the Germans would simply laugh at the message and declare it a forgery, as many American skeptics were already doing. Who but the British would gain by such a message? But to everyone’s surprise, Zimmermann himself admitted to having sent the message.

In March 1917, three more American ships were sunk by German submarines. The Russian Revolution was underway, and the shape and direction of the war was changing rapidly. What had begun as a war of territory between several large empires was fracturing into a war of ideology. The U.S. could not stand aloof any longer. When Wilson gathered his cabinet, the members all agreed that they were essentially already at war with Germany. On April 2, the president addressed Congress to request permission to declare war; that same day, a report came in that twenty-eight Americans had been killed when the steamship Aztec was torpedoed. Wilson did not mention the Lusitania in his speech, but its presence was felt; it had become such a familiar shorthand for German cruelty and immorality that there was no need to name it. Congress agreed. On April 24, the first American destroyers sailed from Boston to Queenstown in Ireland, just up the coast from where the Lusitania’s survivors and dead had come ashore. Crowds waved American flags in greeting. The British marine artist B.H. Gribble immortalized the scene in a painting that would be purchased in due course by a cousin of Teddy Roosevelt’s, who would hang it in the Oval Office when he became president in 1933, and who is credited with suggesting its title to the artist: The Return of the Mayflower.