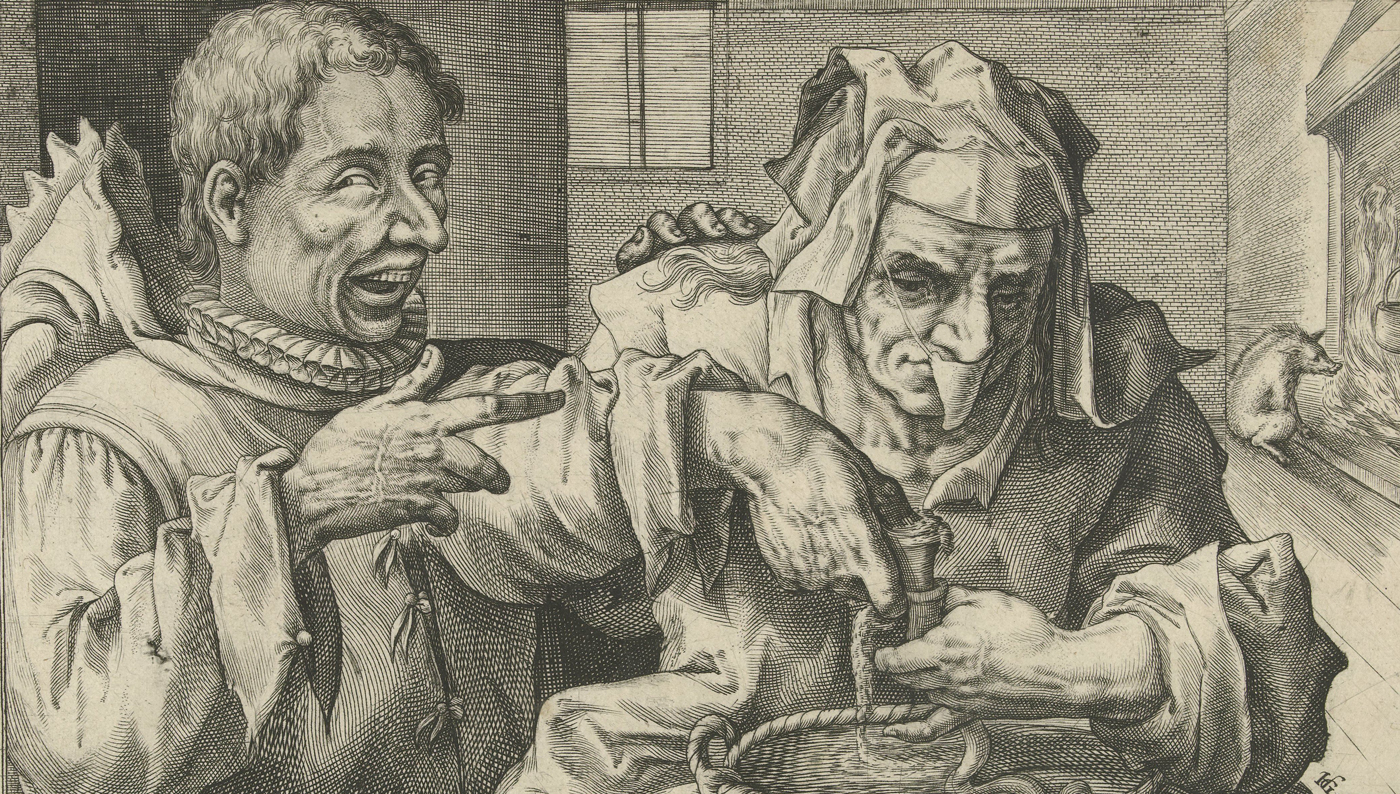

Satire on Hygiene, Crispijn van de Passe (I), after Hendrick Goltzius, 1574–1637. Rijksmuseum.

Wash four distinct and separate times, using lots of lather each time from individual bars of soap.

—Howard Hughes

Uncleanliness, which breeds disease and death, is not only a self-destructive but highly immoral habit.

—Nikola Tesla

Donald Trump’s weaknesses as a presidential candidate are so vast and varied that Hillary Clinton hardly has time to hit them all. But the handshakes at their first debate may have unnerved him as much as any verbal jab: Clinton was coming off a bout of pneumonia, and Trump is a confirmed germaphobe. Afterward he awkwardly slunk away from center stage instead of shaking hands with moderator Lester Holt. Perhaps the forced, fleeting contact with the opponent he had long derided as unhealthy was all he could bear in that moment.

Trump once called handshaking “barbaric” and described it as one of the “curses of American society” in his 1997 book The Art of the Comeback. Despite one feeble primary attack from Jeb Bush on this point, he nonetheless hasn’t failed to press the flesh in the course of his raucous candidacy. Nor did he risk alienating the electorate with an expressed fear of microbes. An admittedly biased Purell hand sanitizer survey conducted in 2010 held that “2 in 5 American adults (nearly 92 million people)—have hesitated to shake hands with someone because they were afraid of germs.” How widespread germaphobia, or mysophobia, might be is difficult to quantify, but if the popular tendency to self-diagnose the affliction is anything to go by (see, for example, BuzzFeed’s “26 Struggles That All Germaphobes Will Understand”), it likely falls into a class of neuroses viewed as prevalent, socially acceptable, and even harmless.

Yet mysophobia is typically considered a symptom or manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder, which has serious effects on at least 2 percent of the population—more common than either panic disorders or bipolar depression. Why do we sometimes dread infection to the point of sterile isolation? In September 2015, researchers led by Chantal Abergel and Jean-Michel Claverie of the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique discovered Mollivirus sibericum, named for the Siberian permafrost where the virus resides. Called a “giant” virus because it can be seen without a microscope, it provoked alarmed headlines including “Frozen Giant Virus Still Infectious After 30,000 Years,” “The Great Arctic Thaw Could Release Giant Viruses,” and “Rise of the Frankenviruses.” The Washington Post ran a debunker cautioning readers not to “freak out”—after all, M. sibericum can set up shop only inside amoebas.

Even so, we take whatever precautions we can, and our front line of defense in this battle speaks to the anxiety and mistrust that accompanies a handshake: handwashing. Half the time, our hands connect us to an environment; the rest of the time, they’re probing our most intimate areas. They are uniquely adapted to transfer sickness, a vector much harder to manage than fluids. This insight can be attributed to both Florence Nightingale, commonly regarded as the founder of modern nursing, who implemented hand hygiene in the treatment of wounded British soldiers during the Crimean War, and to the Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis, who in 1846 deduced that the women dying of “childbed fever” in his Vienna maternity clinic had been infected by students who hadn’t cleaned their hands after dissecting cadavers. The stakes were clear: stem the tide of preventable deaths.

Despite the public health impact of Nightingale’s and Semmelweis’ work, handwashing is often trivialized, as anyone who has witnessed somebody skip past the sinks after visiting a public restroom knows. It was not until the mid-twentieth century, which saw the American restaurant boom and the identification of many foodborne pathogens, that the importance of daily manual hygiene spread beyond hospitals. In its first decade, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (then the Communicable Disease Center) focused primarily on malaria mosquitos; it then studied biological warfare as it related to the Korean War, followed by STDs and tuberculosis, before finally promoting handwashing education in response to outbreaks of illnesses such as Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria the 1970s and 1980s. It wasn’t until 1993 that the FDA issued the Food Code that mandated those “Employees Must Wash Hands” signs. Recently the CDC found that, on average, “healthcare providers clean their hands less than half of the times they should,” while “studies have shown that there is no added health benefit for consumers...using soaps containing antibacterial ingredients compared with using plain soap.”

Somehow, then, we fail on two fronts: Either we gravely underestimate the importance of handwashing, or we buy into misleading marketing that ignores the clear perils of overreliance on antibiotics. Both attitudes are unscientific. Is it obtuse ambivalence or our latent imperfection that keeps us from “winning” the fight against germs? “Who among us really washes their hands in such a way as to satisfy the requirements of food handling?” asked chef Anthony Bourdain in his book about Typhoid Mary, positing a kind of original sin when it comes to human cleanliness—there will always be some stain that doesn’t wipe off. That’s why germaphobes can be driven to irrational extremes of precaution; that’s why white supremacists adopted the “one-drop rule” to establish inferior bloodlines and Donald Trump Jr. compared terrorists to a few poisonous Skittles in a bowl of innocuous ones. But, aside from a few Silicon Valley billionaires and religious-test demagogues, nobody seems to truly believe we can fully eradicate that which rots us from within or without. The terrors of nature are too complete and too effective. They do not discriminate based on economic class, social status, ethnicity, or nationality.

Perhaps that’s why, for every science-fiction fantasy in which a utopian civilization has eliminated all plagues (like Arthur C. Clarke’s 3001: The Final Odyssey), we have dozens that dramatize the great leveling and internal collapse precipitated by unforeseen, undetectable aggressors. Reactions to news stories about newly discovered but long-dormant strains of germs typically invoke these scenarios rather than colonial smallpox blankets or the 1918 flu pandemic. The Post once jokingly referred to the “bad Val Kilmer movie” The Thaw, while other commentators refer an early episode of The X-Files, “Ice,” which found Agents Mulder and Scully up against an extraterrestrial parasite in a remote Arctic lab, its carriers one by one turning first suspicious and then pathologically violent. It owes a debt to John Carpenter’s The Thing, a cinematic masterpiece of Reagan Cold War paranoia—and paranoia is closely related to ideas of contamination—that in turn is a remake of 1951’s The Thing from Another World, itself an adaptation of John W. Campbell Jr.’s 1938 novella Who Goes There?

The idea, in all its guises, is simple: at the ends of the earth, a small band of humans unleashes an alien force capable of disguising itself as a terrestrial being. Imitating the entities it kills or inhabits, it becomes an epidemic contained within the desolate, lifeless landscape—until it figures out how to escape and spread around the globe. This is precisely what’s terrifying about Carpenter’s version of the tale: the Thing arrived in a spaceship but may no longer properly know what it’s doing. Like its distant B-movie cousin the Blob, it divides and conquers according to advantage, yet pursues its survival mindlessly. It is, one inuits, like a virus, which is to say a dire and savage form of unintelligent life.

And not for nothing have we wrestled over the quandary of whether viruses are, in any meaningful sense, alive. Scientific American paints the problem this way:

For about 100 years, the scientific community has repeatedly changed its collective mind over what viruses are. First seen as poisons, then as life-forms, then biological chemicals, viruses today are thought of as being in a gray area between living and nonliving: they cannot replicate on their own but can do so in truly living cells and can also affect the behavior of their hosts profoundly. The categorization of viruses as nonliving during much of the modern era of biological science has had an unintended consequence: it has led most researchers to ignore viruses in the study of evolution.

Since first emerging in the sixteenth century, germ theory has challenged the concept of Homo sapiens’ supremacy in subtle ways that dragons and devils never could: they project into distant futures and untouchable pasts that have nothing to do with us. Steven Millhauser ties this knot of dread in the short story “The Invasion from Outer Space.” Contrary to the blockbuster draw of the title, contact with extraterrestrial life involves no ray guns, spaceships, or little green men. Instead the township confronts a kind of unicellular algae, yellowish powder that floats down onto the planet on cosmic winds. The humans, denied the catharsis of a showdown with another race of self-aware bipeds, are disappointed by these piles of dust.

Then they realize it’s a soft coup:

We have been invaded by nothing, by emptiness, by animate dust. The invader appears to have no characteristic other than the ability to reproduce rapidly. It doesn’t hate us. It doesn’t seek our annihilation, our subjection and humiliation. Nor does it desire to protect us from danger, to save us, to teach us the secret of immortal life. What it wishes to do is replicate. It is possible that we will find a way of limiting the spread of this primitive intruder, or of eliminating it altogether; it’s also possible that we will fail and that our town will gradually disappear under a fatal accumulation…The invader has entered our homes.

Millhauser’s vision of a motiveless intruder from nowhere has roots in spontaneous generation and miasma theory, discredited spooky pseudoscience that contrasted divinely created mankind with simple organisms and pestilence, allegedly born from nonliving or decaying organic matter. Who Goes There? opens with an extended malodorous riff, as if Campbell’s shapeshifting Thing were the product of fetid human enterprise and not an autonomous creature.

The place stank. A queer, mingled stench that only the ice-buried cabins of an Antarctic camp know, compounded of reeking human sweat, and the heavy, fish-oil stench of melted seal blubber. An overtone of liniment combated the musty smell of sweat-and-snow-drenched furs. The acrid odor of burnt cooking fat, and the animal, not-unpleasant smell of dogs, diluted by time, hung in the air.

Lingering odors of machine oil contrasted sharply with the taints of harness dressing and leather. Yet somehow, through all that reek of human being and their associates—dogs, machines, and cooking—came another taint.

As those who witnessed the worst of the Black Death might attest, phobia and panic exacerbate the impact of disease; the origin of the threat is often less of a concern than how it will harm us or scramble our behavior. Researchers are only now discovering the direct effects of the Zika virus on adult brains, though mere misinformation and hysteria about it have already had an observable impact. The Thing, meanwhile, given the all-male cast, accusatory plot twists, and notoriously hair-raising blood test scene, is occasionally read as an allegory for the AIDS crisis despite hitting theaters in 1982, just a year after the syndrome was first clinically observed. Chronology is similarly subverted by those who believe that AIDS was developed by the U.S. government in the 1970s, potentially with the aim of decimating gay and African American communities, though various documented cases of HIV predate any such conspiracy timetable. “I am sure people know where it came from,” Wangari Muta Maathai, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, told Time in 2004. “And I’m quite sure it did not come from the monkeys.”

Her suspicion is not wholly anomalous. Plum Island, New York, a government property maintained by the Department of Homeland Security, is the site of a bioweapons program that, according to dubious investigations by truthers such as lawyer Michael Christopher Carroll and former Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura, can be blamed for domestic outbreaks of West Nile virus and Lyme disease. (Hannibal Lecter mocks the place as “Anthrax Island” when Clarice Starling tries to tempt him with the promise of a supervised vacation there in The Silence of the Lambs.) These legends derive in part from midcentury visits by Erich Traub, a Nazi brought to our shores by Operation Paperclip, though Carroll seems more frightened by the possibility that we may accidentally release nefarious plagues of our own design out of ineptitude.

Is it a comfort to imagine civilization steering these horrors, no matter how evil that makes us? War against microscopic enemies warps our psychology as surely as the climate change debate. Ignoring our hypothetical borders and riding the currents of globalization, germs became geopolitical and polarizing agents—in New World settlers’ smallpox, in Ellis Island’s quarantines, in the ghettos of World War II. They serve as political symbols for today’s anti-vaccination crowd, whose skepticism of medicine has “gone viral,” with all the randomization and epidemiology of media exposure the phrase entails. The politics of germs are present in the claims of Anatoli Brouchkov, head of the Geocryology Department at Moscow State University, who says that he “started to work longer” and hasn’t had the flu for the past two years because he injected himself with a 3.5-million-year-old bacteria that he personally discovered, like M. sibericum, entombed in Siberian permafrost. “After successful experiments on mice and fruit flies, I thought it would be interesting to try to inactivated bacterial culture,” he told the Siberian Times, explaining that because trace amounts of the germ show up in the region’s water, and the Yakut people there “seem to live longer” on average, “there was no danger for me.”

Perhaps nowhere is the existential, elemental dread of mysophobia clearer than in white nationalists’ rants about minority contagion and in accused germaphobe Donald Trump’s dog-whistle denunciation of immigrants, who take on the proportions of a swarming, cancerous mass in his rhetoric. Whether it’s a Western democracy hostile to hopeless refugees or Howard Hughes performing his stranger domestic rituals, what people fear is being overrun, defiled, or invaded in a way that cannot be overcome or negated—except by the most drastic cleansing of all. Few places we go in the course of a life are as antiseptic as the morgue.