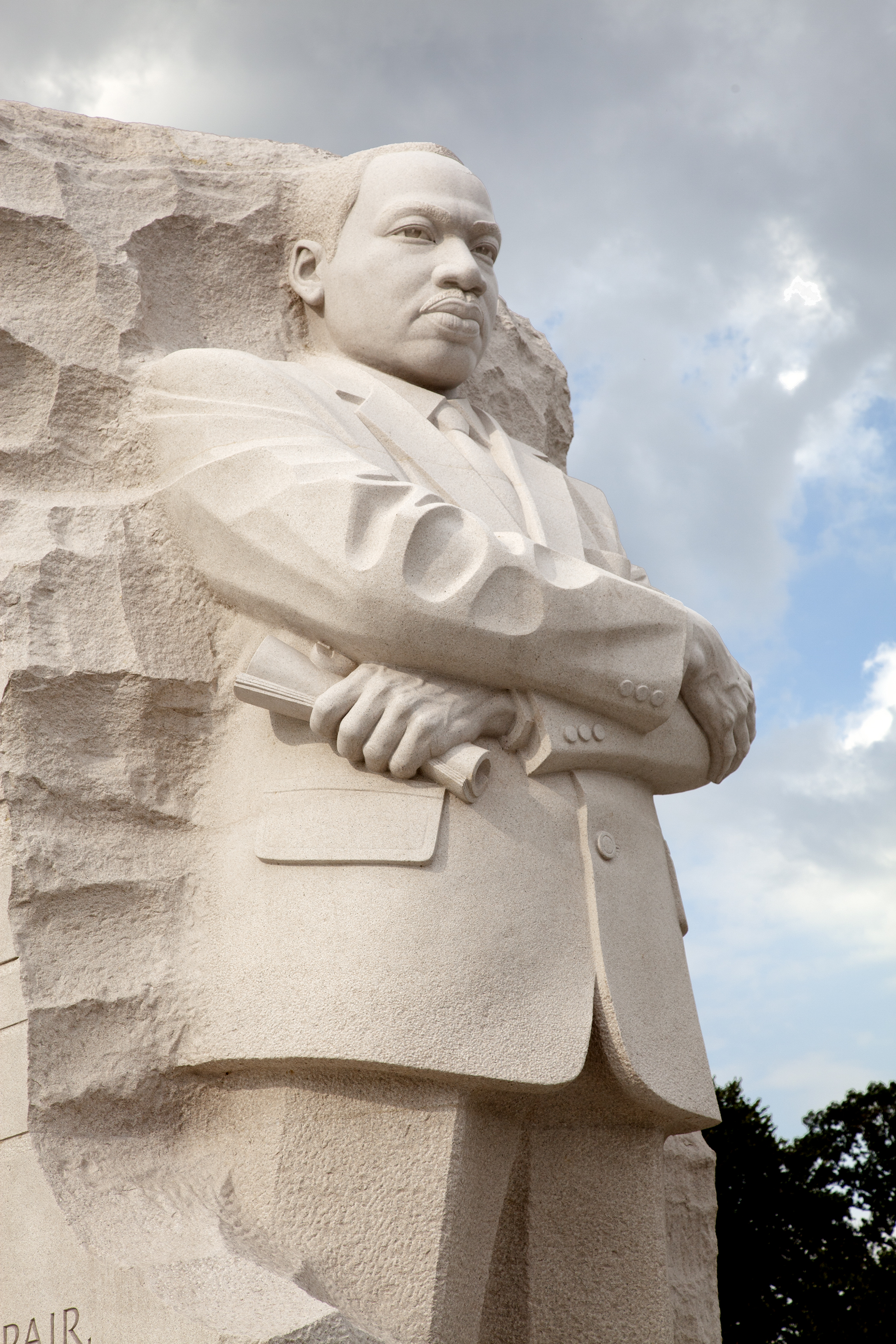

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, Washington, DC, 2011. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

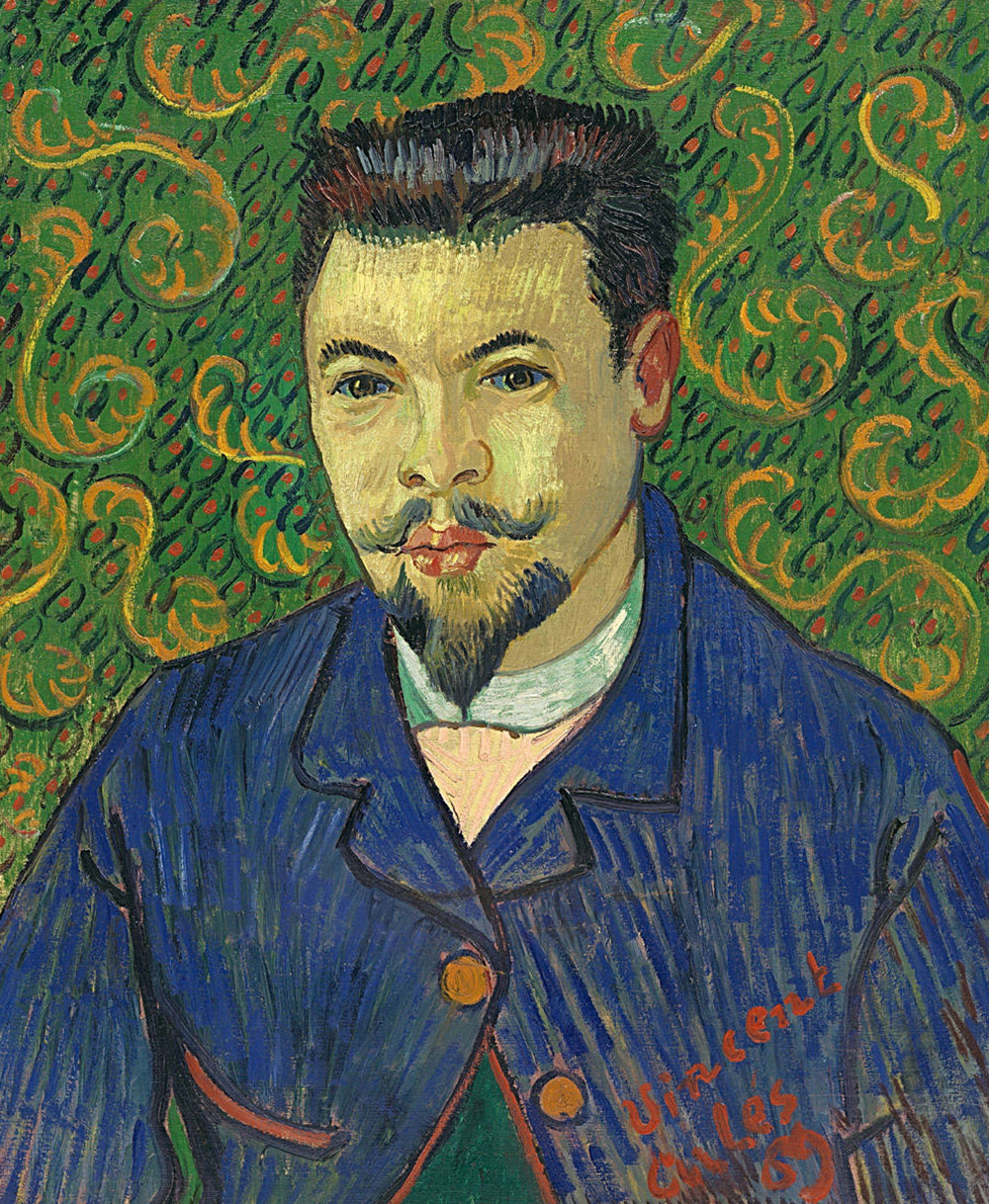

“Ah, the portrait,” Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in 1888, “the portrait with the model’s thoughts, his soul—it so much seems to me that it must come.”

To van Gogh, portraits were not merely a replica of flesh and blood. Rather, the drama of color—expressed through the creative liberty of the artist—revealed the “true man” who would have been hidden by an artist more concerned with precision.

The Postimpressionist weighted subjectivity higher than accuracy. In 1889 van Gogh painted Dr. Felix Rey, who cared for the artist after he mutilated his ear in Arles, France. A green background punctuated by orange flourishes and red dots makes the doctor pop, and what would be the whites of Rey’s eyes are painted light blue. In his royal blue jacket of broad brushstrokes, Rey looks at once stern and comforting. Van Gogh could not help but paint the man who had been so sympathetic to him with so much heart and perspicacity. Yet Rey did not care for this illustrative baring of his soul—he later admitted he was “horrified” by the portrait’s eccentricity. Rey’s vision of himself and van Gogh’s vision of Rey were worlds apart. But the mind of the artist, not just the hand, enhanced the character of the portrait. The presence of the artist’s perception in the portrayal of the subject was not folly but clarity of artistic vision and recognition of shifting viewpoints.

When art and U.S. politics enthusiasts gazed at Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley’s official portraits of Michelle and Barack Obama in early 2018, they were well acquainted with this subjectivity in perspective. The reception of the colorful, daring paintings was mixed. But despite any disappointment surrounding the almost garish background of Wiley’s portrait of Barack, and the delight over Michelle’s unexpected expression in Sherald’s, these paintings depict single moments in time, sore thumbs among many other moments depicted in the National Portrait Gallery in which the Obamas were rendered inferior or invisible. In context, the portraits are a jarring representation of black power within a history of black persecution.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s many sculpted likenesses exist in a similar realm. His statues inhabit the all-too-familiar role of saint among sinners. Sculptural tributes to King proliferate as valiant depictions of Confederate figures topple. Cities all around the United States are removing and relocating monuments to the Lost Cause, pressured by protests of the statues as homages to people who endorsed and committed crimes against humanity. But many statues of known white supremacists still stand resolutely, propped up by the advocacy of concerned citizens, state laws barring statue removal, or lack of local interest in the issue. At the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta, King is surrounded by segregationists and Confederate generals, like alleged Ku Klux Klan head John Brown Gordon.

I am reminded of the duality of America as I stare up at this King statue, a jacket draped over his arm and a book in his hand, poised to walk toward the street that bears his name. Dedicated on the fifty-fourth anniversary of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 2017, the statue stands on a dark pedestal of Georgia granite. His famous words from that August 28, 1963, speech are etched around the top of the pedestal, as if forming protection from the impure or a portal for the ancestors. To be black in a country that recognizes its racist past and present but does not willingly reckon with it is to be torn and disoriented. But this tension is not unfamiliar. The statue’s unwavering defiance despite being surrounded by monuments to racist former Georgia governors—including slavery supporter Joseph Emerson Brown and segregationist Eugene Talmadge—mirrors that of King’s nonviolence and civil disobedience. “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue,” King wrote in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” And the clash of the Two Americas—the one that values freedom and the one that takes it away—was a problem that King acknowledged and sought to reconcile.

If any memorial is worthy of holding space for such discord, it is that of the capitol of the last state readmitted to the Union, the state that also birthed this minister and activist. The “spiritual geography” of the South, as author Michael Eric Dyson once called it, ignites the land and informed King’s work. Martin Luther King Sr. was born in Stockbridge, Georgia, a city where I lived for much of my childhood. North of that city lies the house King Jr. grew up in. Ebenezer Baptist Church is a couple of miles from my current home. On my drives, I pass the eponymous street where John Wesley Dobbs—civic leader, friend of the Kings, and christener of the “Sweet Auburn” neighborhood—lived with his wife and children. Not far from there, a bridge displays a black-and-white painting of King’s visage alongside a quote from one of his sermons: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.” Our memory of King is woven into the landscape of the city. And though we celebrate King, Atlantans are as accustomed to these historic monuments as we are to humid heat and congested traffic.

King was the author of many lectures, speeches, sermons, and writings over the course of his abbreviated life. Yet only a small percentage of those words tend to resound in the current cultural consciousness—not because they’re somehow better than his others, but because we decided they would. Plucking his words like the best grapes in a bunch, we appropriate King’s sentiments to help craft our own stories. That’s how we end up with spectacles like the 2018 Super Bowl commercial attempting to sell Ram trucks with King’s views on service from “The Drum Major Instinct” sermon. It was not lost on astute viewers that in that same 1968 sermon, King addressed the manipulative goals of advertisers and the pitfalls of the manufactured public persona. The King presented through these tweet-sized excerpts of his monumental proclamations is the same King presented through his public sculptures. Every bronze King with his hand raised in expressive oration, every stone King with a look of selfless determination is decontextualized and frozen in time because we made it so. Taken separately, each statue imagines one fleeting beat in King’s storied and dynamic life. Taken together, the statues compose a curated assemblage that reflects our desire to construct an icon made of hardy and awe-inspiring materials. Rather than attempting to convey some kind of greater truth about King—as van Gogh wished to do with his portraits—many King statues present polished, rigid versions of the adored orator. Though by nature statues romanticize and magnify the legacies of historical figures who were more human than superhero, the overwhelming number of monuments dedicated to Dr. King emphasizes just how eager we are to idealize his activism and messages of hope and peace among races and nations. And this idealization is evident beyond the art world. Politicians, pundits, and everyday people have misconstrued King’s words to justify “color-blind” policies or deem black rights activism divisive, constructing a false utopia where race does not matter and can be ignored without repercussion.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, DC, the most high-profile of the attempts to set these imagined universal desires in stone, has been dismissed as a failure. Standing thirty feet tall, the centerpiece features a serious Dr. King carved into white granite. This “stone of hope” emerges from a “mountain of despair,” two boulders yards behind it. Fourteen of King’s quotes border the memorial. The sculptor and its workers were Chinese, a fact that critics denounce considering King’s focus on advancing African American civil rights. King’s stony stare, crossed arms, chunky suit, and enormous size spell dictator and in no way embody his humanity, they say. And to top it off, an inaccurate quote had to be removed from the monument years after it debuted. “I was a drum major for justice, peace, and righteousness,” it read, a cherry-picked version of a statement the civil rights leader made during a sermon two months before his death. Not only did King not utter these words, but he would never be so pompous, the memorial’s detractors argued.

Ella Baker, instrumental in the launch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, would have disagreed. A champion of collaborative leadership and critic of the subjugation of female organizers and leaders in the movement, Baker was not quiet about her disdain for leaders who had risen to cult-like status. “Martin…wasn’t the kind of person you could engage in dialogue with, certainly, if the dialogue questioned the almost exclusive rightness of his position,” she said in a June 1968 interview. Of course, people intent on tearing apart the civil rights movement viewed King as larger than life, too—such a sentiment was explicitly expressed by the government when it put targets on his back because of his great stature. Calling King’s “I Have a Dream” speech “demagogic,” head of FBI intelligence operations William Sullivan foretold danger in King’s power. “He stands head and shoulders over all other Negro leaders put together when it comes to influencing great masses of Negroes,” Sullivan said. “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national security.” One of COINTELPRO’s goals in 1968 was to “prevent the rise of a ‘messiah’ who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement.” King was one of the figures on a messianic path. And his rise to messiah ended when he was assassinated on April 4, 1968.

Like the Obama portraits, the Washington memorial (dedicated in 2011) is in stark contrast to the surrounding war veteran memorials and monuments honoring past presidents, a reminder of America’s contradictory values and problematic history. And it is predictable in its caricature of Dr. King as the wellspring of hope in an otherwise hopeless society. King, the sole figure depicted on the imposing monument, is portrayed as a lonely and self-important purveyor of optimism. Though King is known to have displayed male chauvinism, particularly toward female movement leaders, he did not claim to be the only one lighting the way. Removing the condensed quote from the back of the centerpiece could not fix this woeful misrepresentation. The inspiration for the memorial is from the “I Have a Dream” speech: “With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” King did not claim to be the stone carved out of mountain—in fact, King emphasized how only our collective efforts would catalyze the transformation necessary to achieve freedom and harmony. Aggrandizing King’s role as a hero who accomplished major civil rights feats without obstacle and without blunder is a motif present when viewing the dozens of King memorials in the U.S. through a wide-angle lens, thought that’s not reflective of reality.

King points assuredly as he stands atop a monolithic marble pedestal at Morehouse College. At the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama, a bust of King stares solemnly ahead, as if contemplating the weight of his work. Homage to King in Atlanta is a steel sculpture that presents a silhouetted but indisputable Dr. King with his arm outstretched. The ubiquity of this specific portrayal of King’s character is undoubtedly a by-product of the wistful sentimentality and rose-colored glasses through which the world looks back at his legacy. The longing for King to be the perfect peacemaker and evangelist of love, rather than the complex, outraged, self-sacrificing person he was, typifies the impulse to preserve the purity of our “good” leaders—especially the black ones—within the morally stained history of America. It is also reminiscent of society’s tendency to view African Americans as superhuman, indestructible, and principled despite their hardships. King’s status as a real-life “Magical Negro” is all but spotlighted in the Washington memorial.

Yet the monument’s missteps are also its strengths. It succeeds in an area where other memorials come up blank: its self-awareness. Exaggerating King’s size to five times his actual height, inflating his pride, and hardening his edges show that we shaped that towering image of King. Both King’s allies and his enemies noted his meteoric rise to civil rights stardom. Perhaps the memorial’s imperfections serve double duty: highlighting our hyperbolic views of King’s character while challenging us to rethink the edited narrative we’ve constructed around his legacy. King’s contributions to civil rights were incontrovertibly world-changing and monumental, the memorial suggests, but what are the consequences of elevating his status to myth, making him a legend? Ella Baker, ever the community builder, brought him back down to earth: “The movement made Martin rather than Martin making the movement.”

The King that the movement made is present among the multitude of King sculptures in America. Take the image that Geraldine McCullough sculpted of King that now stands across the street from a statue of Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois. Dedicated in 1988, this bronze statue of King nonchalantly flings his jacket over his left shoulder, a lean in his step, his necktie loose. He looks at ease, yet full of charisma and energy. But if memorials are to be judged on their ability to invoke a person’s legacy and commemorate some truth of his life, then the best are those that allow the most space for complexity and rumination. Dr. King looked toward a better future for black Americans and ultimately paid for it with his life. But he was not immune to the agonies of being black in twentieth-century America, nor the privileges of being a man in a patriarchal society, no less the difficulties of being a flawed human under scrutiny of the public eye.

A steel and bronze tribute to King called Radiance (1989) in Toledo, Ohio, presents four King heads with different expressions mounted on a reflective sphere at cardinal directions. Though decried as ugly and not nearly as impressive as grander King tributes, the artwork depicts a King who has been disembodied posthumously. He has many faces, yet his humanity is absent. As spectators look into the shiny sphere and a reflection stares back between King’s countenances, they are forced to see King as their equal—also constantly changing, also human, even if cast in bronze.

It is impossible to carve the nuances of a life as meaningful as King’s into a statue. It is also impossible to distill the impact of a life as intricate as King’s into a few acres in a public park. Each monument is at worst an uninspired tribute to an American hero and at best a thoughtful contemplation of our connection to a life offered to the cause of racial equality. For decades we’ve honored King through memorials and statues commemorating his activism, commitment to justice, and messages of love and peace. But there are plenty of other black leaders from U.S. history whose legacies also have been recognized through public sculpture: Harriet Tubman, Octavius Catto, Rosa Parks, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X. And America’s wrongs haven’t gone unacknowledged. In Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham, Alabama, a sculpted water cannon is aimed at statues of cowering black teenagers. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, opened in Montgomery, Alabama, in April 2018, holds America accountable for its history of racial terrorism by documenting in steel the names of lynching victims across the country. Even if our selective memory has flattened King’s complexities, his memorials still make up only one storyline in the grand and tangled narrative told through all of the monuments we choose to build.

In the last years of his life, King turned his sights toward economic injustices, and his ideology and campaigns met brick walls of resistance. But the King that persists in our memories is not this King. We remember him as a leader beloved by all races, despite his radicalism—an unshakable beacon near the end of a dark tunnel. Though we’ve repressed facets of King’s character from our collective memory, the sheer number and breadth of King memorials signifies our understanding of his mortality and its gravity, even if we have not fully deciphered his soul, as van Gogh so aspired to in his portraits. But at a time when polarization reigns and empathy falters, it’s a relief to know that America can still fervently honor a legacy marked by so much dissonance and revolution.