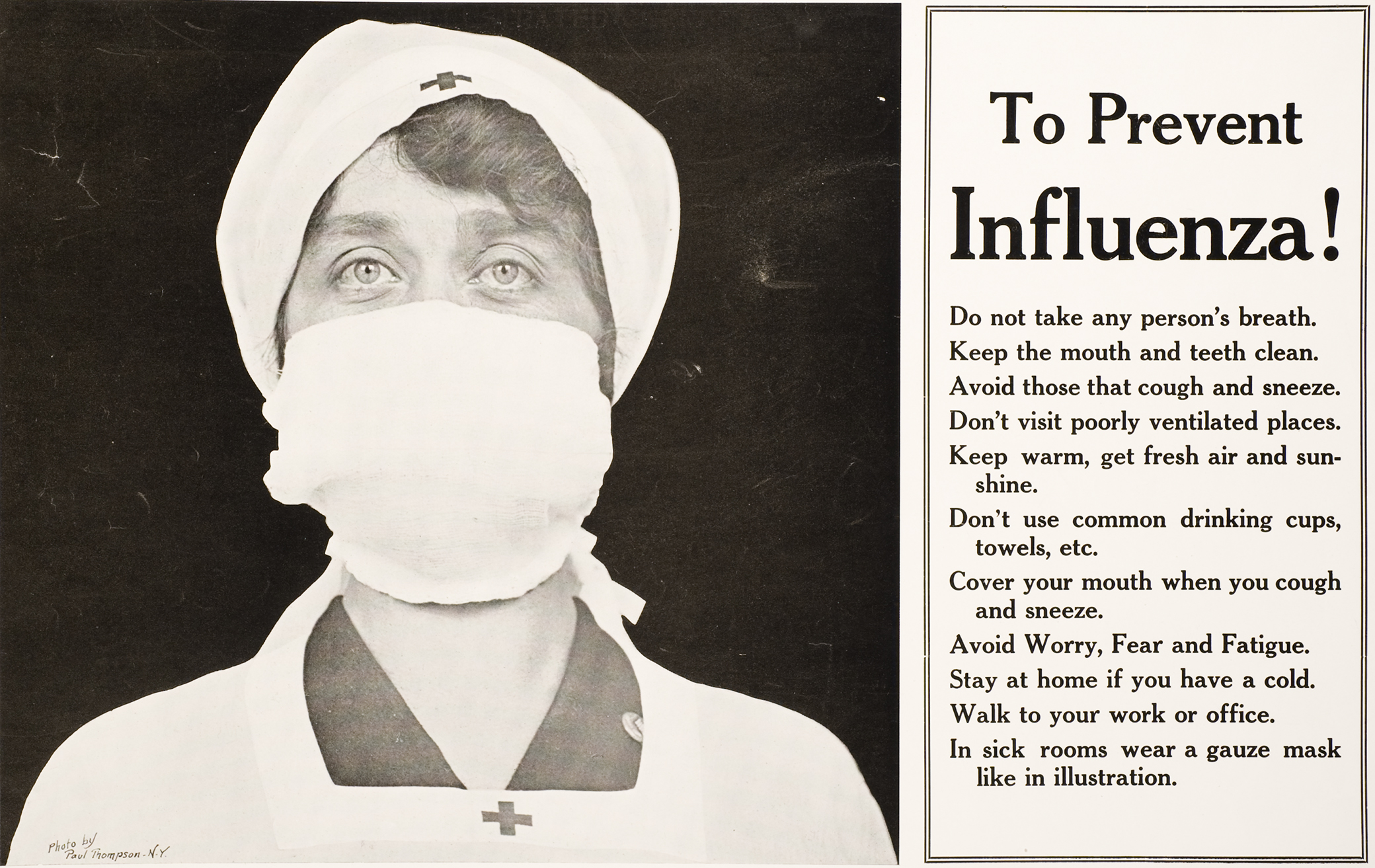

“To Prevent Influenza!” poster, from Illustrated Current News, 1918. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

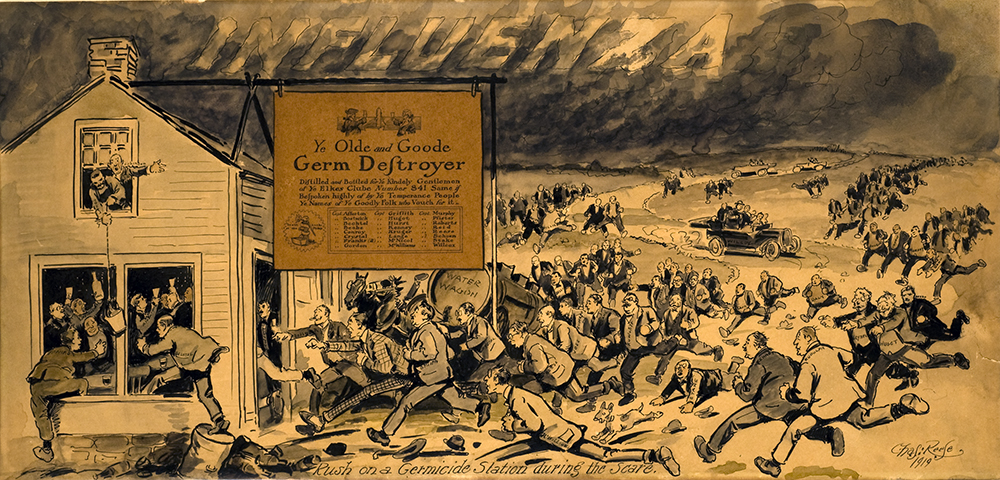

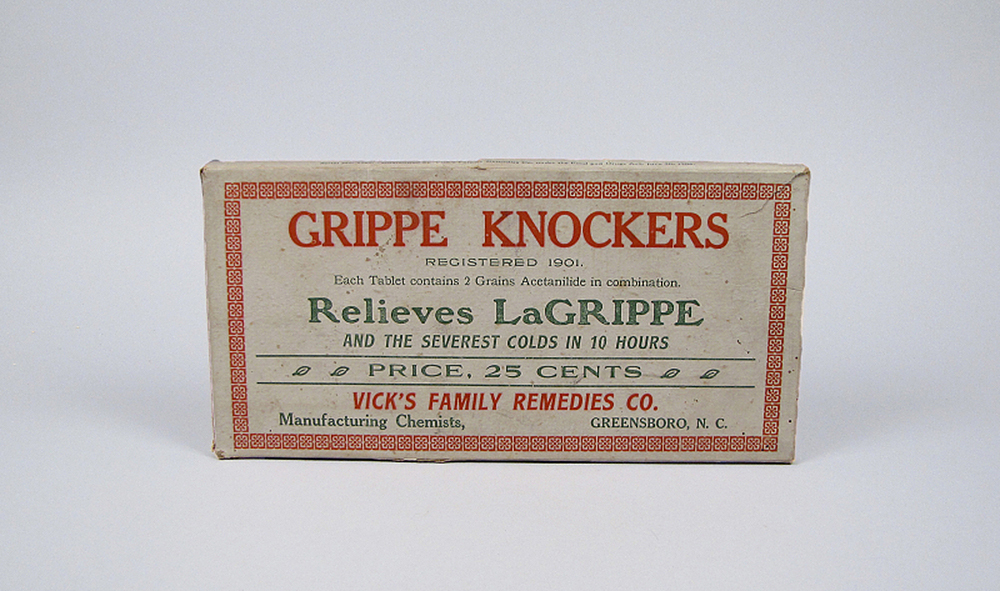

As the 1918 flu continued its campaign of global terror, food and pharmaceutical manufacturers seized on the commercial potential of the epidemic. Respectable proprietary brands bought advertising space alongside quacks and snake oil salesmen, all keen to persuade a desperate public to purchase their wares. Alongside over-the-counter products, frightened families also turned to folk remedies, traditional and reassuring cures familiar to their heritage, whether this be onions, asafetida (a fetid-smelling herb historically used for chest complaints), or opium. As the mortality rates soared, so too did the willingness to try something, anything, to save themselves and their loved ones from a horrible death. And while attempts to develop a vaccine against Spanish flu floundered, doctors pioneered other methods to care for its victims, from the “rooftop cure” where patients were exposed to the elements to an experiment with potassium permanganate on British public schoolboys. From the apparently innocuous first wave during the early spring of 1918 to the escalating second wave of Spanish flu that gripped the world in the later months of the year, daily newspapers carried an increasing number of advertisements for influenza-related remedies as drug companies played on the anxieties of readers and reaped the benefits. From the Times of London to the Washington Post, page after page was filled with dozens of advertisements for preventive measures and over-the-counter remedies. “Influenza!” proclaimed an advert extolling the virtues of Formamint lozenges. “Suck a tablet whenever you enter a crowded germ-laden place.” Another advertisement announced “as Spanish Influenza is an exaggerated form of Grip,” readers should take Laxative Bromo Quinine in larger doses than usual, as a preventive measure. For those who had already succumbed, Hill’s Cascara Quinine Bromide promised relief, as did Dr. Jones’s Liniment, previously and mysteriously known as “Beaver Oil” and intended to provide relief from coughing and catarrh. Demand for Vick’s VapoRub, still popular today, was drummed up by press adverts warning of imminent shortages:

DRUGGISTS!! PLEASE NOTE VICK’S VAPORUB OVERSOLD DUE TO PRESENT EPIDEMIC.

Americans were informed that it was their patriotic duty to “Eat More Onions!” as part of a “Patriotic Drive Against the ‘Flu.’ ” One placard proclaimed:

An onion car arrived today

Labelled red, white, and blue

Eat onions, plenty, every day

And keep away the “Flu.”

An American mother took this suggestion to extremes, and fed her sick daughter syrup made from onions before wrapping her in onions from head to toe. Fortunately, the outcome was successful and the child survived.

Conventional medical advice for the treatment of influenza included morphine, atropine, aspirin, strychnine, belladonna, chloroform, quinine, and, disturbingly, kerosene, which was administered on a sugar lump. Alongside these, folk remedies thrived. If a product from the drugstore failed to alleviate the symptoms, many patients and their families turned to more traditional methods. One popular remedy in South Africa was to place a block of camphor in a bag and tie it around the patient’s neck. One eight-year-old girl, who was taking no chances, announced that she was wearing a camphor bag around her neck “to keep off the Germans.” The practice was so widespread that, over half a century later, an elderly South African lady in a nursing home, who had survived the 1918 outbreak, refused inoculation against the 1969 epidemic of Hong Kong flu. “Not for me,” she maintained. “I still have my camphor bag.” In North Carolina, young Dan Tonkel had taken to wearing a bag of asafetida around his neck, in the belief that the stinking extract would protect him. “It smelled to high heaven,” he recalled. “People thought the smell would kill germs. So we all wore a bag of asafetida and smelled like rotten flesh.” In Philadelphia, Harriet Ferrel was rubbed with tree bark and sulfur, and forced to drink herbal teas and take drops of turpentine and kerosene on a lump of sugar. Harriet was also subjected to the asafetida treatment but was philosophical: “We smelled awful, but it was okay, because everyone smelled bad.” Robert Graves’ “Welsh gypsy” housemaid had an even more unusual form of protection, consisting of “the leg of a lizard tied in a bag around her neck.” She was the only person in the Graves household who did not develop Spanish flu.

Whiskey had always been a traditional remedy for colds and influenza, and whiskey prices soared in the United States during the epidemic. In Denmark and Canada, alcohol was only available by prescription, while in Poland brandy was regarded as highly medicinal. One brave soul in Nova Scotia recommended fourteen straight gins in quick succession as a cure for Spanish flu. The result of this experiment was unknown; if the patient had survived he had doubtless forgotten the proceedings entirely. In Britain the Royal College of Physicians stated that “Alcohol Invites Disaster,” a conclusion which was ignored by many. The barman at London’s Savoy Hotel created a new cocktail, based on whisky and rum, and christened it “the Corpse Reviver!”

In the universal panic of the Spanish flu epidemic, many believed that the air itself was poisonous. One woman in Citerno, Italy, sealed up her house so effectively that she died of suffocation. Lee Reay of Meadow, Utah, recalled one family who sealed their house up. They plugged keyholes, sealed the windows, and even closed the dapper on the stove. Roy Brinkley’s father, a sharecropper in Max Meadows, Virginia, decided that fresh air could be fatal during the epidemic and sealed up his wife and four children in one room. The family spent seven days sitting around the wood-burning stove until it caught fire. As his family fled the house and took refuge in the vegetable patch, Brinkley was convinced that the fresh air would kill them. For the rest of his life, Roy remembered a sudden rush of fresh air and the sight of cabbages, as big as washtubs. But, once outside, the entire family soon recovered.

Excerpted from Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History by Catharine Arnold. Copyright © 2018 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.