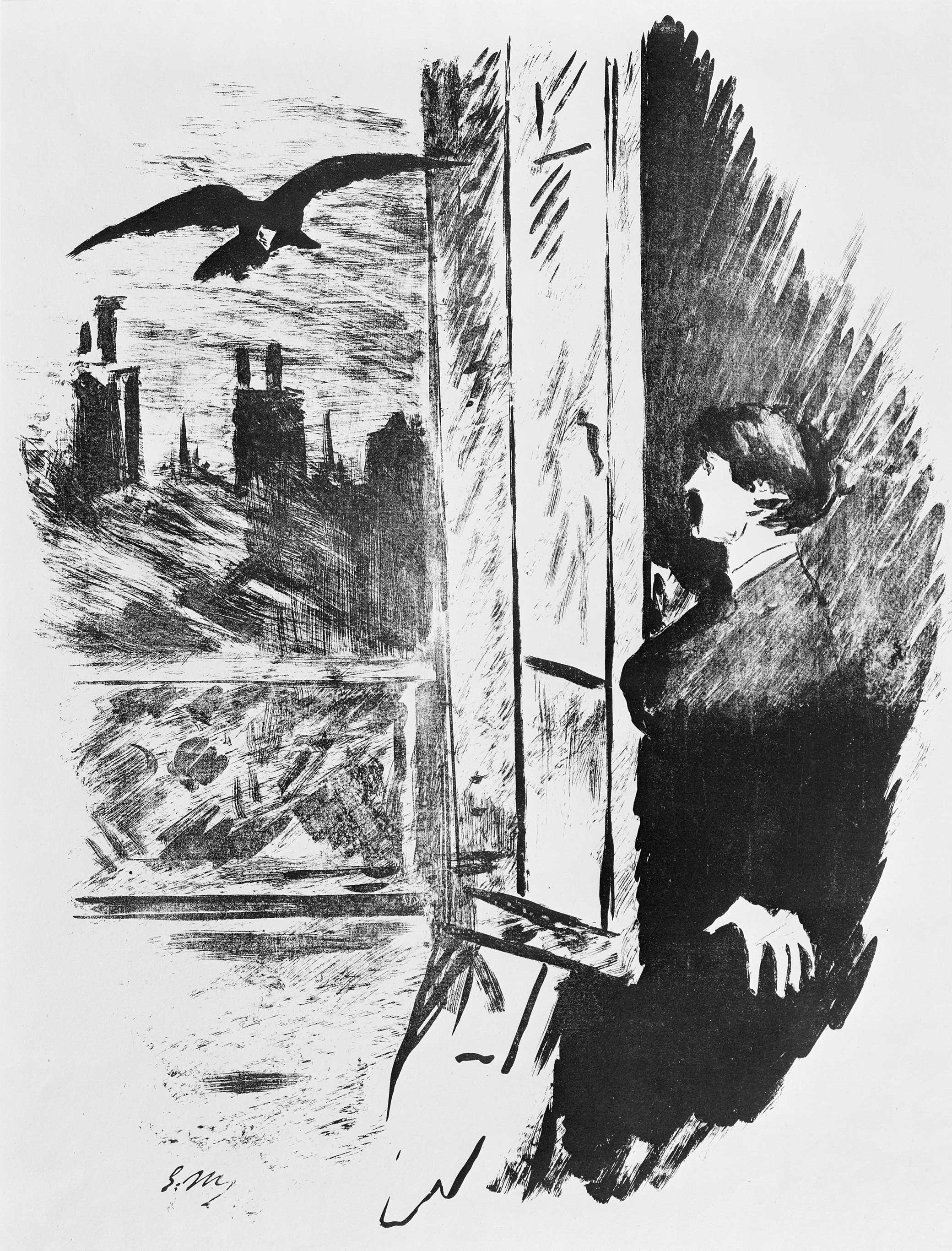

Open Here I Flung the Shutter, illustration to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” by Edouard Manet, 1875. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924.

Type “Edgar Allan Poe” into your preferred image search engine, brace for impact, and press Enter. Instantly you hit a wall of chalk-white faces, each conveying a mixture of despair, dyspepsia, grief, wonderment, and wounded pride. Some are actual daguerreotypes, while the rest are fan art or movie stills inspired by those antique likenesses. In every case, one has the distinct feeling that misery could not ask for better company. This is Poe.

Now try searching “Poe Osgood portrait” instead. What comes up this time is a face totally different from those in the previous set. It can’t be the same person. There is color in his cheeks and light in his eyes, and his brow looks quite unburdened. The expression registers as neither menacing nor miserable, but magnanimous. This too is Poe.

It is Samuel Stillman Osgood’s more human version of the poet, novelist, and critic that interests us here. That the portrait has become emblematic of a close friendship between Poe and Frances Osgood, the artist’s wife, makes it still more surprising, because Poe is not supposed to have had friends. Even granting that authors are not their works, it is hard to imagine chatting amicably with the man behind “The Pit and the Pendulum.” Yet evidence shows that plenty of people did. Poe formed many generative friendships through the years, even as time, circumstance, and his own complicated temperament conspired to deny him others. In the twilight of his short life, having survived or somehow alienated everyone he loved most, Poe seemed to feel the absence of friends as both a fate worse than death and a harbinger of it. He did not want to be alone with himself.

“I believe God granted me the spark of genius,” Poe told his acquaintance Thomas Morrison Alfriend a few weeks before his death, “but he quenched it in misery.” From the beginning, life certainly was not disposed to do him many favors. Born to stage actors David and Eliza Poe in 1809, he saw his tubercular father desert the family and his mother succumb slowly and painfully to the same disease before he was three years old. Wealthy, childless Frances Allan, visiting the Poe household in her Victorian capacity as a sympathetic woman of means, took pity on a resourceless boy and made him her foster son, complete with an expanded moniker: Edgar Allan Poe. As all his biographers have noted, for the rest of his life—and, remarkably, even after death—Poe would depend for his survival on the charity of others.

In our mind’s eye, the child Poe is haunted by the ghost of his adult self. Signs of sadness or struggle swell out of proportion, blanketing his early life in uniform gloom. No Gothic anecdote can surprise us. Of course little Edgar is rumored to have stood up in the family carriage while riding past a cemetery and exclaimed, “They will run after me and drag me down!” It would be more surprising if there were no such rumor. When Poe confesses to a friend in later years that his youth was “sad, lonely, and unhappy,” fans instinctively judge these words an understatement.

But the veil of perpetual sadness that we draw over Poe’s young life does the child and his world a disservice. He was not some imp of the perverse, but a lively, charismatic, and intelligent boy who showed both promise and fine personal qualities to anyone paying attention. Neighbors effused about the “lovely little fellow, with dark curls and brilliant eyes, dressed like a young prince.” As he grew older, Poe proved to be an excellent student, particularly of French and Latin. His accomplishments were not limited to the classroom; he was a strong swimmer and a natural at field sports. He even taught one of his friends how to play bandy, a sport similar to ice hockey. (My kingdom for an image of Edgar Allan Poe on skates.)

By 1826 Poe was attending the University of Virginia. While there were limits to how much sway the orphaned son of impoverished actors could hold over his wellborn Southern schoolmates, Poe’s personality and keen intellect won him friends and admirers. His love of gambling didn’t hurt his popularity either, though it would severely strain the goodwill of his foster father, John Allan. Surviving letters show Allan’s growing disgust with such prodigal behavior. As Poe’s debts and Frances Allan’s tuberculosis both worsened, Allan’s dialogue with Poe swung between acrimony and mercy. Though Allan had praised his foster son’s literary talents when Poe was a child, he rejected writing as a career for the young man and insisted on something more practical. Forced to leave UVA when Allan stopped financing his studies, an eighteen-year-old Poe enlisted in the U.S. Army, posing as twenty-two-year-old Edgar A. Perry and quickly attaining the rank of sergeant major. He was discharged, entered West Point, and impressed his superiors there for a while; but the poet finally bested the soldier, and “gross neglect of duty” and “disobedience of orders” brought his military career to a close.

From UVA onward, Poe’s ambitions as a young poet seemed to grow in inverse proportion to his shrinking funds. By the time he was ready to publish his second volume of poems, an expanded reprise of the first that included the cosmic meditation “Al Aaraaf,” Allan had cut off his allowance, leaving him no way forward. Yet that second volume, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems, appeared in 1829, after Frances died and shortly before he entered West Point. His fellow privates, sympathizing with the orphan’s disappointed hopes, took up a collection among themselves so that his book might come out as planned.

In other words, Poe’s friends saved him. They did not have to do this. Nor would the experience often repeat itself over his turbulent career.

Baltimore. New York. Philadelphia. Poe’s adult life saw him crisscross between these cities, finding in none of them the full measure of security and acceptance that he craved. Now determined to live by his pen, he kept body and soul together by writing horror stories and working as a magazine reviewer, all the while hoping for a lifeline from some unlikely source. In his last letter to John Allan that we know of, Poe laments, “Without friends, without any means, consequently of obtaining employment, I am perishing, absolutely perishing for want of aid…for God’s sake pity me and save me from destruction.” There was no answer. Thus Poe lost his father a second time.

The American literary landscape of Poe’s era was a steep cliff with few footholds. Since the lack of an international copyright law enabled U.S. publishers to pirate European works with impunity, they had little incentive to support homegrown talent. Meanwhile, American authors poured their frustrations into fiery debates over the essence of their national literature. It was all too easy a place to make enemies, and the hotheaded Poe made plenty. Some of his troubles, like the fallout from a baseless feud with cultural giant Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, were his own fault, while others were inflicted on a critic who would not kowtow to cliques or praise terrible writing merely because it came from an American’s pen. When he was not excoriating bad books like Morris Matson’s Paul Ulric: Or the Adventures of an Enthusiast (“too purely imbecile to merit an extended critique”), he drank heavily and endured nervous depression, his overall health never again so firm as in boyhood. His career was often the kind of disaster from which one cannot look away. Some did more than look. Onetime ally Thomas Dunn English accused him in print of both plagiarism and ugliness. Poet Elizabeth Ellet leveled possibly accurate charges of an affair between Poe and Frances Osgood, severing their personal and professional association. Most damaging of all, the critic Rufus Wilmot Griswold, Poe’s rival in literature and love (they both flirted with Osgood), fought him to the grave and beyond. His fictional “memoir” of Poe, published just months after the latter’s death, was a hatchet job worthy of the Rue Morgue or the House of Usher’s depths.

The sense of being cast adrift in a vast and hostile world finds expression in Poe’s only completed novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, published in 1838 and later disavowed by the author himself as “a very silly book.” The plot follows Pym, a young wanderer frustrated by his lack of an inheritance, and his closest friend, Augustus, on an epic maritime journey, tracing a course that leads to the South Pole and finally (probably? somehow?) off the face of the Earth and onto a higher plane of existence. Long before that metaphysical ending, Poe inflicts images of intense physical and psychological pain on the reader. During the harshest sequence of all, three sailors dying of starvation resort to cannibalism, casting lots to decide which of them will be devoured. Even dear Augustus finally dies and is eaten by sharks. Pym’s journal places his death on August 1, which was also the death date of William Henry Leonard Poe, an older brother raised separately by relatives in Baltimore, whom Edgar had always yearned to know better. Poe is sometimes most candid when most imaginative.

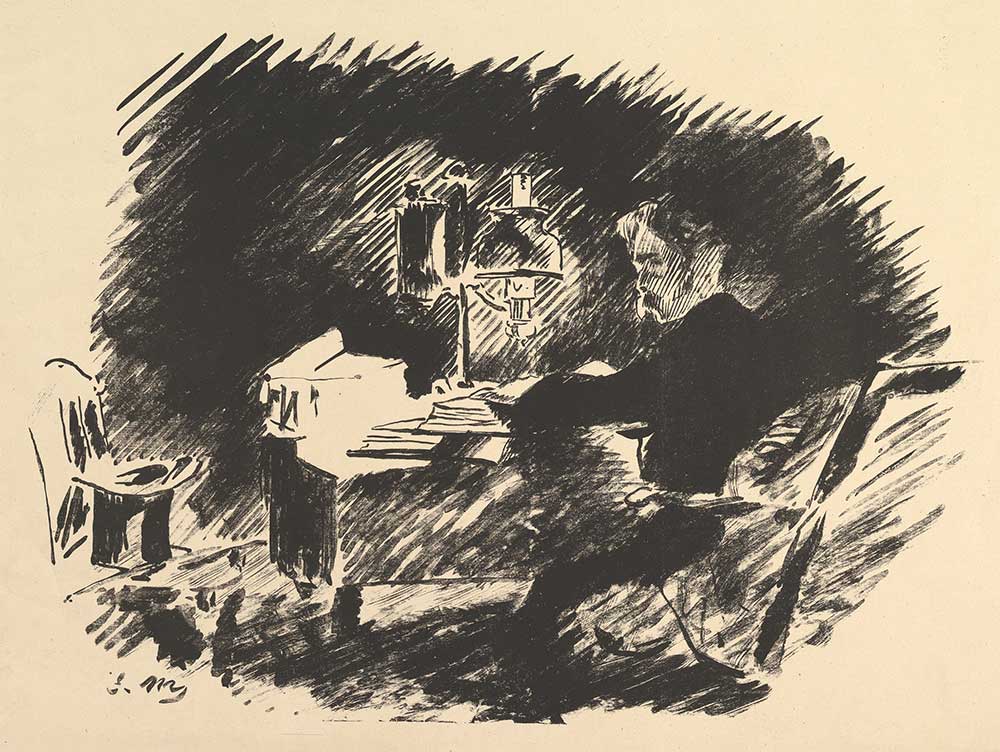

I was discussing this novel with a student recently. We agreed that Poe can more easily represent people eating one another than enjoying true friendship. If dread, betrayal, and violence sprang naturally from his imagination, perhaps it was life as a “Magazinist” (his word) that seeded them. Yet in this line of work Poe also demonstrated his best self. George Graham, whose eponymous magazine thrived under Poe’s editorship, would later praise him as “punctual and unwearied in his industry—and the soul of honor, in all his transactions.” Steering each new issue of Graham’s, The Evening Mirror, and The Broadway Journal to print while hungry competitors shadowed the boat, ready to usurp his role if circulation dipped, he became, as colleague Nathaniel Parker Willis put it, “a man who never smiled.”

Poe must have smiled at some point during 1845, the best year of his literary life. In January he published “The Raven,” a smash hit. He was thrilled by the poem’s success, and later tried to capitalize on it by writing an essay, “The Philosophy of Composition,” that purports to give readers a behind-the-scenes look at his process. Throughout this essay, Poe styles himself as the ultimate clinician, a student of human nature, poetic form, and how they relate. Arguing that words have power as words, apart from their referents, and that aesthetic effect is “the rigid consequence of a mathematical problem,” he propounds a concept of language that would not have its day until the rise of formalism eight decades later.

Scholars agree that “The Raven” was inspired by Charles Dickens’ 1841 historical novel Barnaby Rudge, a rambling panorama of the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots in 1780. Among the cast of characters are a kindly boy named Barnaby and his closest friend, a talking raven named Grip that hops about the novel with cries of “Nobody!” and “I’m a devil! I’m a devil! I’m a devil!” Poe reviewed Barnaby Rudge twice for Graham’s Magazine: first when only three installments had been published (Dickens’ novels almost always appeared first in serial form), and again when the final numbers were out. In the first review, Poe expresses the utmost love for Grip’s character but also the certainty that Dickens had stumbled on a creation whose potential he did not fully understand: “In fact, beautiful as it is, and strikingly original with him, it cannot be questioned that he has been led to it less by artistical knowledge and reflection than by that intuitive feeling for the forcible and true, which is the sixth sense of the man of genius.” Poe’s second review finds his worst fears confirmed. Grip has turned out to be just a funny little talking bird instead of the real devil that Dickens’ readers deserved. “Its croaking chorus,” he opines, “might have been heard prophetically in the course of the drama.” Having found the great English novelist’s vision sorely lacking, Poe would take it on himself to give the devil his due.

This he accomplished using an unforgettable mix of camp and pathos. At the outset of “The Raven,” a man languishes in his study, alone with the memory of his deceased love and the books that have failed to distract from his grief. Suddenly a raven enters the room. Noticing the bird’s power of speech, if also its limited vocabulary (“Nevermore!”), the speaker becomes increasingly consumed by a single question: Is this bird merely the pet of “some unhappy master” or a demon sent to prey on his weak and weary mind?

It would be easy to read “The Raven” as a corruption—or at least a Gothicization—of the sweet interspecies friendship that grounds Dickens’ novel. It would also be right to some extent. But before the bird makes its historic entrance into American literature, Poe’s speaker tries to manifest another kind of encounter on this dreary night:

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

“’Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door—

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;—

This it is and nothing more.”

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

“Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you”—here I opened wide the door;—

Darkness there and nothing more.

As in Pym, Poe’s macabre fantasies suggest a shred of the artist’s inner life. His wife, muse, and best friend, Virginia, was dying of tuberculosis, like his mother, foster mother, and brother before her, when he wrote “The Raven.” With her would go the strongest restraining influence on his unstable nature, as he himself must have known. The fear of something wicked—from outside his study, or else from deep within his own mind—renders the speaker desperate to find an ordinary human guest at his door. How different a universe the poem would depict if someone were standing there to greet the young widower. Instead he finds only darkness.

For as long as Poe is read and remembered, the circumstances of his last days will remain impenetrably obscure. The facts in the case are few. He left Richmond, Virginia, on September 27, 1849, bound for his home in New York. One week later, on October 3, he was found wandering the streets of Baltimore, delirious and without his luggage. In a truly bizarre development worthy of a detective story, he was wearing clothes that did not belong to him. What had happened? “The most commonly accepted theory,” Peter Ackroyd explains in his slim and necessarily speculative biography, “is that he was used as a ‘stooge’ for polling purposes, being dressed up in someone else’s clothes so that he might vote more than once for a particular candidate.” Forced intoxication was often a factor in these election schemes, meaning that Poe’s recently made promise of sobriety may have been broken, albeit against his will.

Whatever the truth, Poe was now suffering from a terrible fever. Told by a sympathetic doctor that friends would soon be with him, he replied that a friend could do no better for him than to blow his brains out. He died a few days later, on October 7, 1849. Four people attended his funeral. Griswold, who did not, wrote a lengthy yet dismissive New York Tribune obituary under an assumed name: “Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.”

Many have grieved since, and Poe’s spark, despite what he told Alfriend, was far from quenched. In fin de siècle France, his writings became almost sacred. Poe’s experiments along the borderline of conscious and unconscious thought presaged those of Rimbaud and Verlaine, while his claim that poetry should provide the reader with an “indefinite” pleasure, not a definite moral, anticipated by four years a similar statement from Théophile Gautier and made Poe a standard bearer of art for art’s sake. To Paul Valéry, Poe’s otherworldly verse came as a revelation, and Charles Baudelaire could not begin his day without offering prayers to God and Edgar Allan Poe.

But aside from the writing, it was Poe’s image as the enfant terrible of American letters—weird, ragged, constantly teetering on the cusp of self-destruction—that established his reputation in France. The symbolists, disdaining bourgeois affectation in favor of all things perverse, found Poe irresistibly repellent. Had these men ever stood in the presence of the sturdy, athletic young private, and felt both his charm and his fervent desire to make good, they might have been horrified.

Explore Friendship, the new issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.