Bowl with leopard, Iran, early thirteenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Lewis Balamuth, 1968.

When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays.

In 1219 Genghis Khan invaded the lands of the Khwarezm-Shahs, a Muslim Turkic dynasty that succeeded the Seljuq Empire in Persia and Transoxania. The Mongol ruler’s armies quickly sacked the cities of Samarkand and Tus but failed to unite Persia under his governance. Minor Mongol and Muslim leaders battled over the region until 1256, when Hülegü, one of Genghis Khan’s grandsons, conquered all of Iran.

Within a few years of Genghis Khan’s invasion, the Persian poet Saadi, then a teenager, left his hometown of Shiraz to study Islamic theology and literature at Baghdad’s Nezamiyeh madrassa. He spent the next thirty years traveling around the Islamic world, avoiding the political upheaval in Persia. The extent of his journey was likely exaggerated in later recollections, but scholars believe that he visited at least Iraq, Syria, and the Arabian Peninsula during this period. He also acquired some fame as a writer of ghazals, or short lyric poems.

Upon returning to Shiraz around 1256, Saadi joined the court of Abu Bakr ibn Saad ibn Zangi, the regional ruler of Fars and a prominent patron of learning and the arts. Abu Bakr’s father was named Saad, leading historians to suspect that Saadi chose his pen name in anticipation of his return to Shiraz, to gain favor with the ruling family. The poet’s birth name was never recorded definitively by his contemporaries.

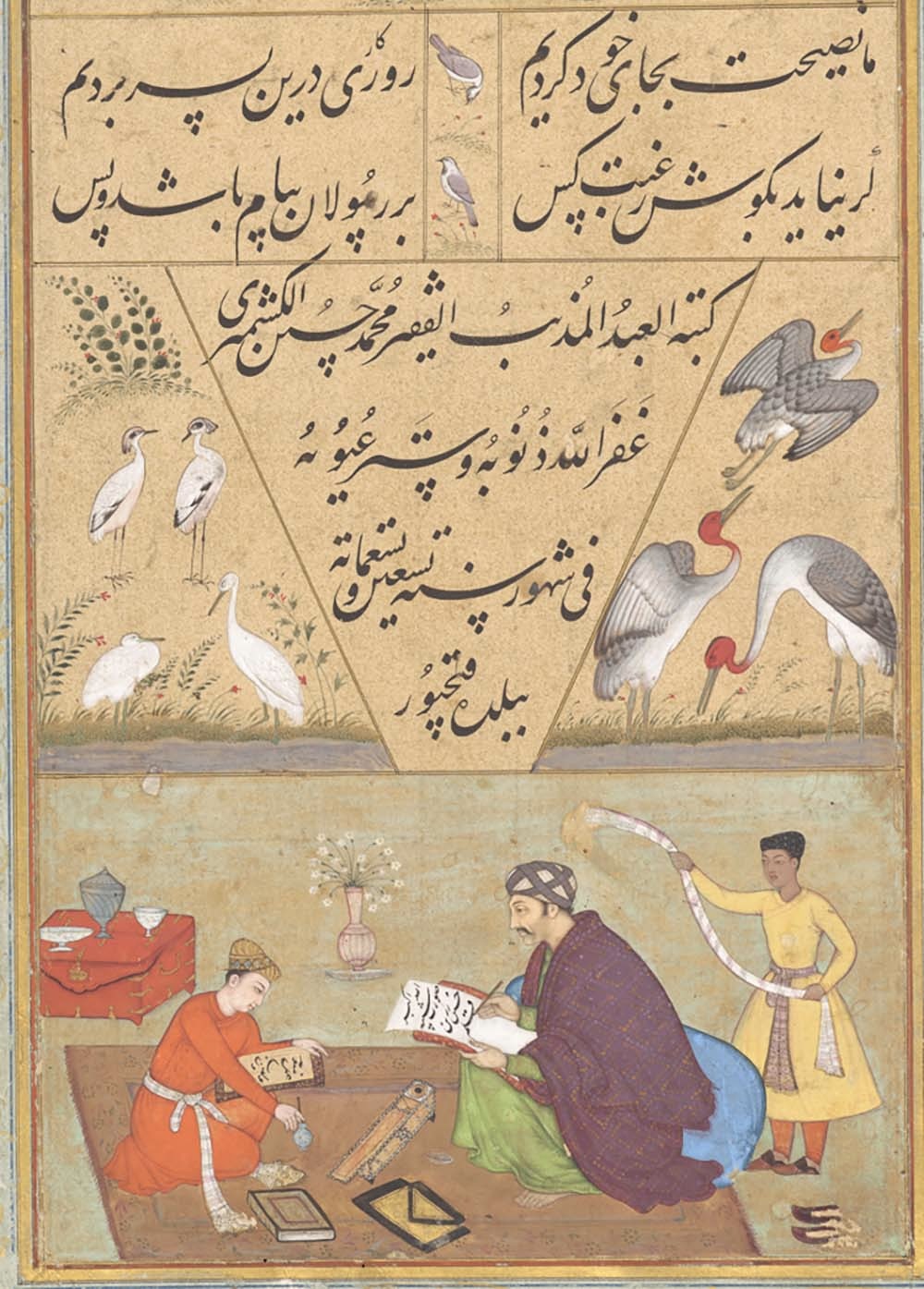

In 1257 Saadi completed the Bustan (The Orchard), a collection of verses meditating on Islamic virtues and moral duties, including justice, contentment, and humility. The following year he finished the Gulistan (The Rose Garden), a series of anecdotes and poetic couplets that treated similar themes. He likely repurposed unused material from the Bustan for the Gulistan, although the latter work was more playful and less moralizing. He wrote in its epilogue that he had intended to sweeten “the bitter potion of instruction…with the honey of facetiousness, that the taste of the reader may not take disgust.”

Medieval Persianate authors and secretaries quickly began to model their prose on Saadi’s writings. The popularity of the Gulistan was quite durable: when the East India Company established colleges in the early nineteenth century for their administrators to learn Indian languages, the Gulistan was required reading for students of Persian. (Munshis, Persian-speaking literary scholars in India, first introduced the British to the text and assisted with its translation.) Francis Gladwin, a professor at Fort William College in Calcutta, completed the first full English translation of the Gulistan in 1806. It was reprinted in the United States in 1865 with an introduction by Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote that Saadi, “though he has not the lyric flights of Hafez, has wit, practical sense, and just moral sentiments.”

He is the poet of friendship, love, self-devotion, and serenity. There is a uniform force in his page, and conspicuously a tone of cheerfulness…The word Saadi means fortunate. In him the trait is no result of levity, much less of convivial habit, but first of a happy nature to which victory is habitual, easily shedding mishaps, with sensibility to pleasure, and with resources against pain. But it also results from the habitual perception of the beneficent laws that control the world. He inspires in the reader a good hope. What a contrast between the cynical tone of Byron and the benevolent wisdom of Saadi!

The sample of Saadi’s advice below comes from James Ross’ 1823 translation of the Gulistan. Ross studied Persian as a surgeon with the company’s army in Bengal. His translation was intended to be more literal than Gladwin’s, so students might closely compare his edition to the original.

Riches are intended for the comfort of life, and not life for the purpose of hoarding riches. I asked a wise man, “Who is the fortunate man, and who is the unfortunate?” He said, “That man was fortunate who spent and gave away, and that man unfortunate who died and left behind. Pray not for that good-for-nothing man who did nothing, for he passed his life in hoarding riches and did not spend them.”

Two persons labored to a vain and studied to an unprofitable end: he who hoarded wealth and did not spend it, and he who acquired science and did not practice it. However much you are read in theory, if you have no practice you are ignorant. He is neither a sage philosopher nor an acute divine, but a beast of burden with a load of books. How can that brainless head know or comprehend whether he carries on his back a library or a bundle of fagots?

Learning is intended to fortify religious practice and not to gratify worldly traffic. Whoever prostituted his temperance, piety, and science gathered his harvest into a heap and set fire to it.

An intemperate man of learning is like a blind linkboy. He shows the road to others but sees it not himself.

A kingdom is embellished by the wise, and religion rendered illustrious by the pious. Kings stand more in need of the company of the intelligent than the intelligent do of the society of kings. If, O king, you will listen to my advice, in all your archives you cannot find a wiser maxim than this: Entrust your concerns only to the learned—notwithstanding business is not a learned man’s concern.

Three things have no durability without their concomitants: property without trade, knowledge without debate, or a sovereignty without government.

Reveal not every secret you have to a friend, for how can you tell but that friend may hereafter become an enemy? And bring not all the mischief you are able to do upon an enemy, for he may one day become your friend. And any private affair that you wish to keep secret, do not divulge to anybody: for, though such a person has your confidence, none can be so true to your secret as yourself. Silence is safer than to communicate the thought of your mind to someone and warn him, “Do not divulge it.” O silly man! Confine the water at the dam head, for once it has a vent you cannot stop it. You should not utter a word in secret that you would not have spoken in the face of the public.

A reduced foe, who offers his submission and courts your amity, can only have in view to become a strong enemy, as they have said, “You cannot trust the sincerity of friends, then what are you to expect from the cajoling of foes?” Whoever despises a weak enemy resembles him who neglects a spark of fire. If today you can quench it, put it out, for if you let fire rise into a flame, it may consume a whole world. Now that you can transfix him with your arrow, permit not your antagonist to string his bow.

When irresolute in the dispatch of business, incline to that side which is the least offensive. Answer not with harshness a soft-spoken man, nor force him into war who knocks at the gate of peace.

So long as money can answer, it is wrong in any business to put the life in danger. As the Arabs say, “Let the sword decide after stratagem has failed.” When the hand is balked in every crafty endeavor, it is lawful to lay it upon the hilt of the saber.

It is wrong to follow the advice of an adversary; nevertheless, it is right to hear it, that you may do the contrary. This is the essence of good policy. Sedulously shun whatever your foe may recommend, otherwise you may wring the hands of repentance on your knees. Should he show you to the right, a path straight as an arrow, turn aside from that and take the path to the left.

Whoever is counseling a self-sufficient man stands himself in need of a counselor.

Whoever does not do good, when he has the means of doing it, will suffer hardship when he has not the means. None is unluckier than the misanthrope, for on the day of adversity he has not a single friend.

Life stands on the verge of a single breath, and this world is an existence between two nonentities.

Whatever is produced in haste goes hastily to waste. I have heard that after a process of forty years, they convert the clay of the East into a china porcelain cup. At Baghdad they can make a hundred cups in a day, and you may of course conceive their respective value.

Nothing is so good for an ignorant man as silence, and if he knew this, he would no longer be ignorant.

In a season of drought and scarcity, ask not the distressed dervish, “How are you?” Unless on the condition that you apply a balm to his wound and supply him with the means of subsistence.

Two things are repugnant to reason: to expend more than what Providence has allotted for us, and to die before our ordained time. Whether offered up in gratitude or uttered in complaint, destiny cannot be altered by a thousand sighs and lamentations. The angel who presides over the storehouse of the winds feels no compunction, though he extinguishes the old woman’s lamp.

O you who are going in quest of food, sit down, that you may have to eat. And O you who death is in quest of, go not on, for you cannot carry life along with you.

A scholar without diligence is a lover without money; a traveler without knowledge is a bird without wings; a theorist without practice is a tree without fruit; and a devotee without learning is a house without an entrance.

Read the other entries in this series: Inez Milholland and Eugen Boissevain, George Washington, Plutarch, Lewis Carroll, Chrétien de Troyes, Yan Zhitui, Nizam al-Mulk, Giovanni Della Casa, Maria Edgeworth, Dan McQuade on basketball manuals, and Leopold Froehlich on syndicated advice columnists.