Death and Life, by Gustav Klimt, 1910–15. Leopold Museum, Vienna.

Three and a half minutes into Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 film, The Seventh Seal, a pale-faced figure clad in a billowing, hooded black robe appears on the screen. His macabre appearance is so iconographic that the audience anticipates his answer when the knight Antonius Block asks, “Who are you?” Death, who agrees to grant Block a short reprieve, is intellectual and existentially aware, even witty, and these qualities heighten his unsettling character. Inspiration for Bergman’s portrayal came from one of Albertus Pictor’s fifteenth-century wall paintings in Sweden’s Taby Church, depicting a skeletal Death figure playing chess with a man.

Bergman is one of many artists throughout history who have striven to personify death: to translate the intangible, unknown end of human beings into an image that can be perceived by the eye and grasped by the mind. Religious belief, devastating illness and war, and cultural developments have all played significant roles in shaping the appearance of death in a particular time and place.

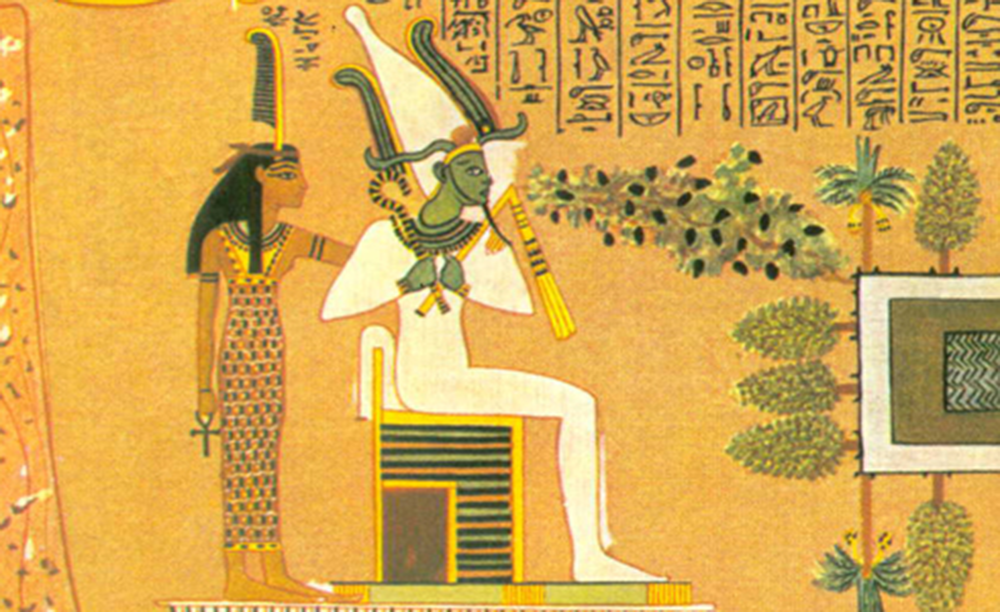

In the ancient world, death was often personified as the lord of the afterlife. Often invoked during funeral rites, he also served as an impartial judge in the underworld. The Egyptian god Osiris was a divine paradigm for the pharaoh, and later all deceased persons, as he himself died and was resurrected. Tomb paintings and wooden statues from as early as the Old Kingdom represented Osiris as a mummified figure, wearing an atef crown—a tall headpiece with white feathers—and carrying a crook and a flail, both symbols of kingship. His skin was either painted black or green, colors that represented the ever-renewing cycle of the natural world. The Hindu god Yama and the Greco-Roman divinities Hades/Orcus and Pluto/Dis fulfilled similar roles as Osiris. Early depictions of death lack any ethical coloring: these underworld gods do not fall into categories of good or evil, but they are treated with due fear and respect.

The Greek spirit Thanatos was not tied to the underworld and thus represented death in a more abstract sense. Son of Nyx, goddess of night, and brother of Hypnos, god of sleep, he was responsible for transporting mortals to the underworld. A fourth-century marble column from the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus depicts Thanatos as a delicate, winged youth with a sheathed sword strapped around his waist. In contrast to the divine underworld kings, Thanatos was a mediator figure, markedly benign in appearance. Greek philosophy espoused an intimate connection between the beautiful and the good, and artistic portrayals of Thanatos as a handsome, lithe boy suggest the emergence of an attitude toward death that embraces its necessity among the intricately woven threads of human existence spun by the Fates.

Christian art adopted the iconography of the rich pantheon of Greek daemons, and we can see echoes of Thanatos in paintings with religious subject matter. Evelyn de Morgan’s 1890 oil on canvas, The Angel of Death, merges Biblical subject matter with an Arcadian landscape and neoclassical figures. The scythe and long cloak signal the angel’s status as an agent of death, but the dappled light on the folds of his robe and the feathers of his wings, the gentle touch of his hand, and his serene facial expression all identify him as a benefactor of divine grace rather than a merciless reaper. Christianity’s promise to the believer of a blessed afterlife strips death of its macabre quality, and this is reflected in de Morgan’s rendering.

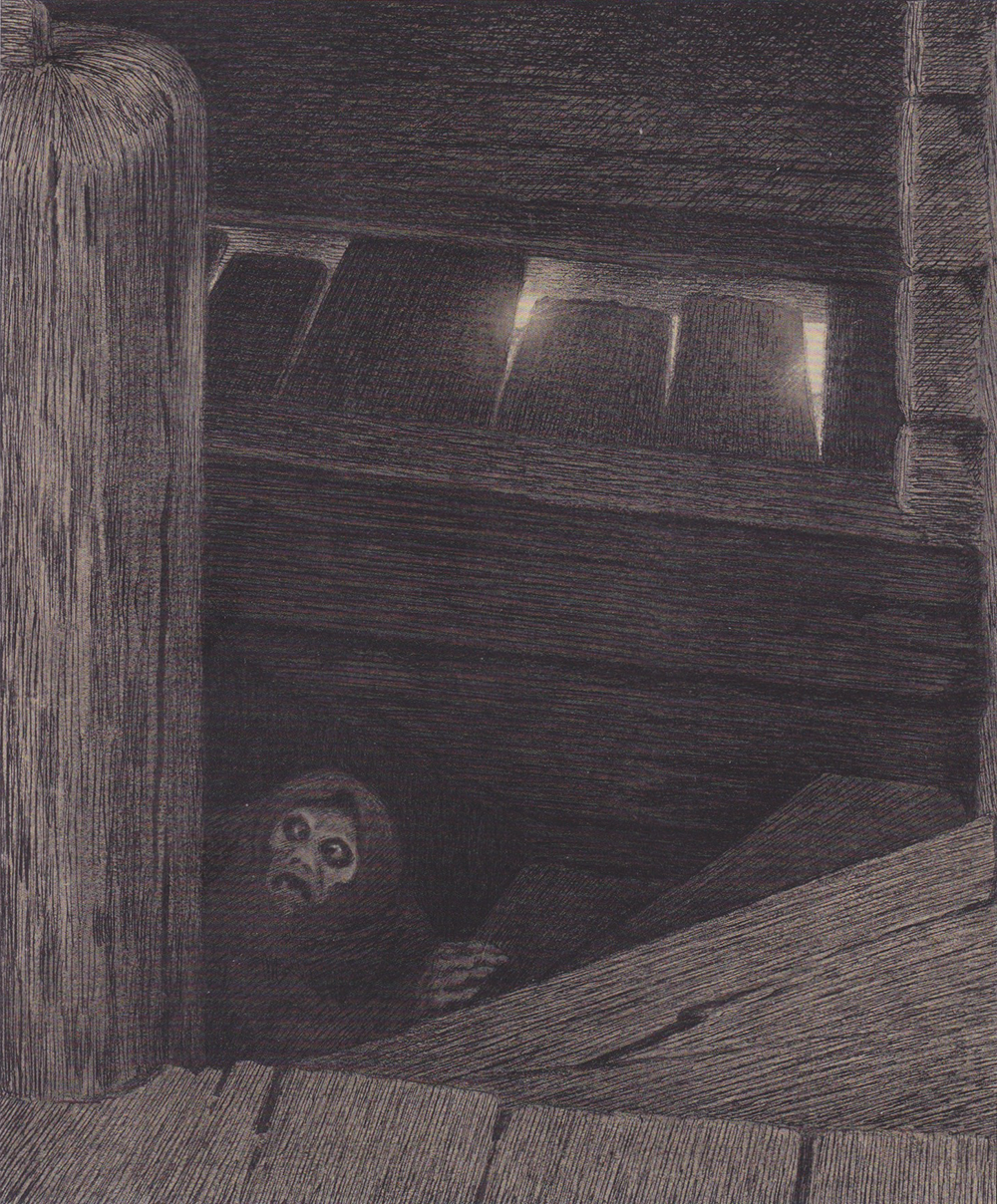

Other cultural traditions represent death as a female figure. The Middle Ages was a period of widespread illness; the Black Death alone killed millions of Europeans. In the church of Saint-André, located in Lavaudieu, France, a fresco dating from 1355 shows death as a tall woman, wearing a scarlet robe and a black veil. She clutches arrows in both hands, and a host of men and women from various social classes fall dead around her, the parts of their bodies commonly afflicted by plague buboes pierced by her arrows. This is not a saintly Madonna offering her restorative healing powers, but a formidable feminine force of wrath and destruction. Similarly, an 1896 illustration by Theodor Severin Kittelsen depicts the Scandinavian personification of the plague. Pesta is a hideous, stooped old hag whose arrival signals plague and death. Instead of arrows, Pesta carries a rake and a broom; according to the myth, if she used the former, some had a chance of survival, but if she used the latter, not one soul would be spared.

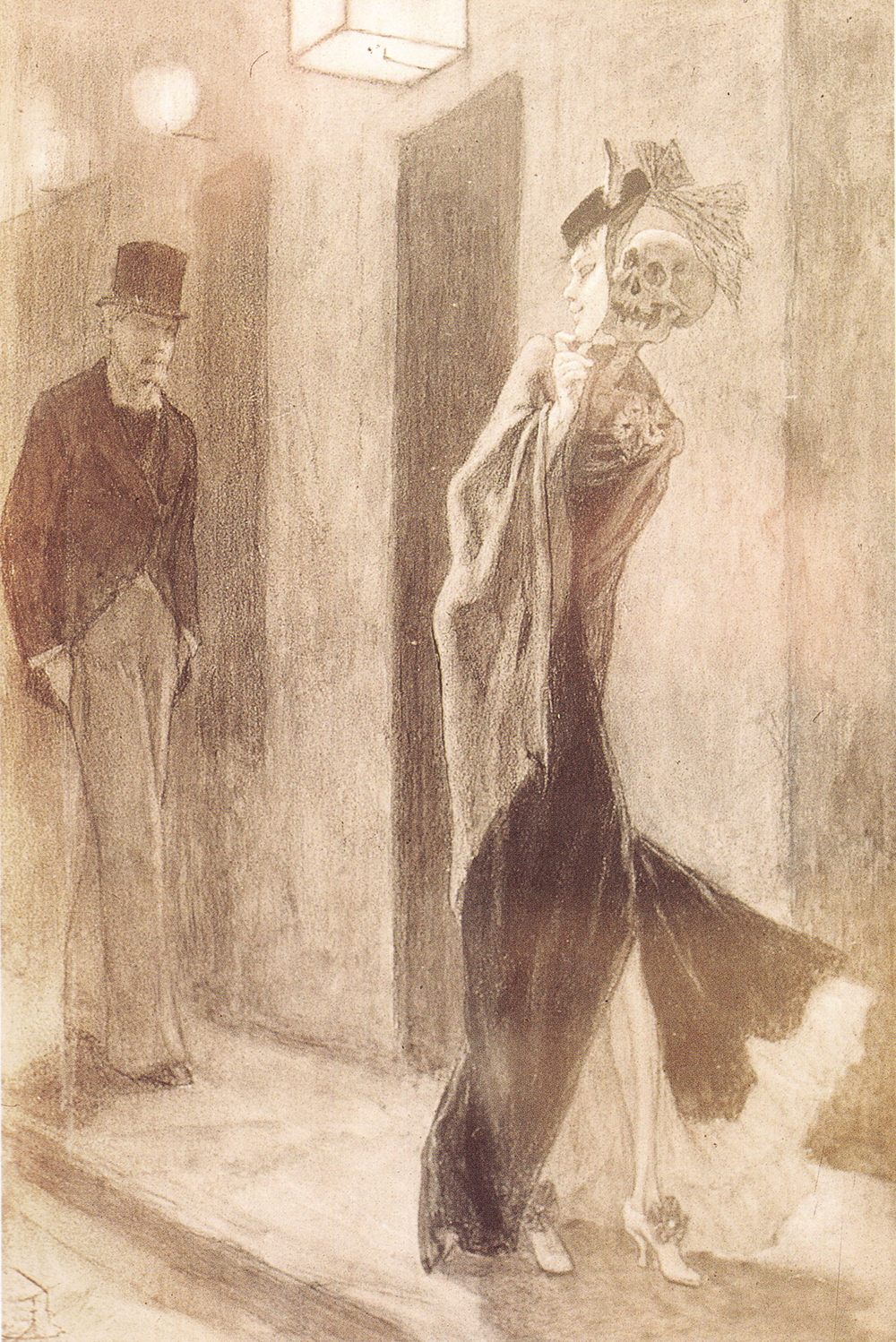

Artists continued to represent death as a dangerous female figure in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In his 1878 drawing The Human Parody, Belgian printmaker Félicien Rops illustrates the transient veneer of feminine beauty. What appears to the approaching gentleman to be a seductive woman clad in a sumptuous black dress is really a grisly skeleton holding a finely painted mask. This is the true parody of human existence, the act of adorning our mortality with external trappings.

Just over twenty years later, symbolist painter and writer Alfred Kubin strips death of any disguise in his pen-and-ink drawing, The Best Doctor. Composed between 1901 and 1902, Kubin’s creation is eerily hermaphroditic: the bare skull sprouts tufts of straggly long hair and the body is an amalgamation of masculine muscular arms and a flat chest with sharply exaggerated feminine curves, outlined by a tight black dress. It could almost be described as a figure in drag. The drawing is a dark reflection on humans’ trust in the saving powers of medicine. Death, supposedly “the best doctor,” is not gently covering the eyes of the deceased man, but forcibly pressing down on his face and smothering him.

As a counterpart to these undesirable depictions, some artists have eroticized death by portraying it as a beautiful young maiden. We see, for example, a female counterpart to de Morgan’s angel of death in Carlos Schwabe’s 1895Death of the Gravedigger. She is elegant and mystical, simultaneously dynamic and statuesque, and her enveloping wings form an arc of grace around her and the dying gravedigger. Schwabe brings to life Baudelaire’s description of Death in “The Death of the Poor” as “an Angel who holds in his magical grip/Our peace, and the gift of magnificent dreams.”

Arguably the most recognizable representation of death is that of the skeletal corpse, a universal symbol that demonstrates death’s power to decompose the human body and serves as an effective memento mori. One popular artistic motif utilizing skeleton imagery is the “dance of death.” Hans Holbein designed a series of woodcuts on this theme in the sixteenth century. In each woodcut, death leads a different individual—a rich man, an abbot, and the emperor, to name a few—to his or her demise. The “dance” is didactic, teaching the viewer that death comes to everyone, regardless of social standing; it is the great equalizer.

Another major motif is the “death of the maiden,” also associated with the “kiss of death.” Two noteworthy examples are a 1517 panel by Hans Baldung and an 1893 painting by Edward Munch. In Baldung’s work, a sallow corpse straddles a woman, gripping the pale, supple skin below her left breast and craning her face back to meet his bony kiss. There is such terror and violence in the scene that it resembles a rape. Munch, on the other hand, creates an atmosphere of extreme intimacy between the skeleton and the woman. Death’s spindly leg juts through the woman’s buxom thighs, and her embrace matches, perhaps even surpasses, his in its ardor. Both artists’ depictions of death are highly sexual, but there is a clear movement from hostility to alacrity.

Death in its skeletal form eventually appropriated the scythe and the long hooded cloak, traditional attributes of the nightmarish Grim Reaper. The Reaper was not always pictured as antagonistic, however. Alfred Rethel’s woodcut from 1851, Death as a Friend, features a skeletal form resembling a mendicant friar more than a reaper. It is a personalized portrait, retaining elements of the benevolent Angel of Death: the reaper’s scythe leans against the wall and he solemnly performs the duties of the dead bell ringer with a downcast, sorrowful expression.

Early twentieth century renderings of the reaper become truly “grim” and allegorical, emphasizing the ruthlessness of death. One cannot help but shudder at Gustav Klimt’s perversely grimacing skull, delighting in any opportunity to take a fatal swipe at the vivid ball of life, in the 1910 canvasDeath and Life. Some of the most grisly images of the Grim Reaper from the period portray death as the bringer of cholera. The cover of the French publication Le Petit Journal on December 1, 1912, shows a towering, corpse-like figure reaping a harvest of diseased humans with his scythe.

The tendency to identify death with the Grim Reaper remains alive in western street art. Inspired by a London cartoon satirizing the “Great Stink” of the late 1850s, notorious graffiti artist Banksy spray-painted a hooded Grim Reaper onto the side of a boat in Bristol harbor in England. (He also recently installed a Grim Reaper driving a bumper car in a parking lot in New York City.) Banksy utilizes historical iconography of death to make us question whether we have, so to speak, cleaned up our act, or whether the “stink” of contemporary society simply seems to be better concealed.

These manifold representations of death may span time and place and be subject to cultural and religious influences, but they reveal a timeless, universal impulse to concretize a phenomenon that eludes human comprehension. In the final scene of The Seventh Seal, we see a silhouetted dance of death, poignantly narrated by the clownish Jof. The last words of the film, however, come from his wife, Mia: “You and your dreams and visions…” Bergman ultimately reminds the audience that artistically rendering death does not give us any power over it—to hold such a belief is a comedic illusion. Death will always paint the final brushstroke on the canvas of our lives.