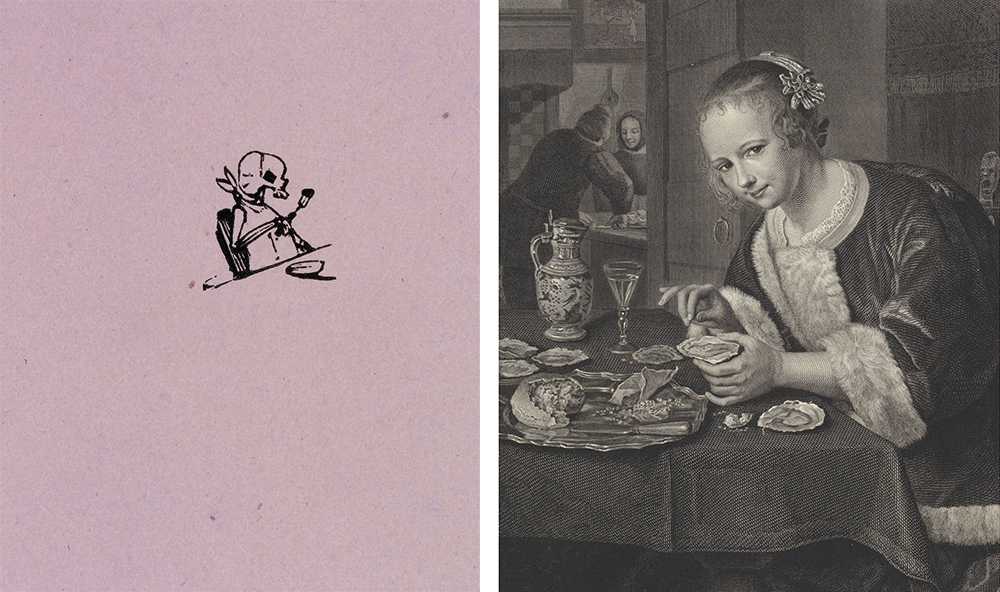

Young Woman Eating Sweets, by Godfried Schalcken, c. 1680. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in support of the Center for Netherlandish Art.

If the food writer M.F.K. Fisher is slightly less well-known than some of her more prominent contemporaries like James Beard or Julia Child, she is no less celebrated. John Updike called her “the poet of the appetites,” while W.H. Auden said, “I do not know of anyone in the States who writes better prose.” David Foster Wallace named his essay “Consider the Lobster” in tribute to Fisher’s third book, Consider the Oyster, which has remained in print since 1941. Her fourth book, How to Cook a Wolf, was reissued in 2020 by Daunt Books Publishing in the UK. Fisher shares with John le Carré a peculiar good fortune in being doubly prized both as standouts in their respective genres (the art of eating well for her, espionage for him) and for transcending those genres’ supposedly inherent limitations as literature. She has been as frequently praised for writing about “more than food” as for writing about food in the first place.

Serve It Forth, Consider the Oyster, and How to Cook a Wolf all helped usher in a distinct postwar era of American culinary assuredness, providing a sense of the nation’s “growing up” and achieving a new culinary parity with the Old World. Her literary bent, her slightly bohemian way of living, the cultural credentials of a private education and three years’ training at the École des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, and her expansive and curious approach to the art of the table kept her from being considered a “mere” recipe writer. She wrote as much of hunger as of food, and her literary reputation was defined by that voraciousness. “Never had a woman written so sensually about her intimate enjoyment of food,” Anne Zimmerman writes in her 2011 biography An Extravagant Hunger: The Passionate Years of M.F.K. Fisher.

Her fifth book, the autobiographical The Gastronomical Me, published in 1943, is a travelogue of chased delights and assignations that provide continual pleasures in need of frequent renewal. “When I write of hunger,” Fisher notes in the book’s foreword, “I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and warmth and the love of it and the hunger for it…and then the warmth and the richness and fine reality of hunger satisfied…and it is all one.” These pleasures hold hunger in abeyance, such that chasing fulfillment can itself become a fulfilling action, and draw an easy, intuitive link between the lover and the diner, such that any single appetite in Fisher’s work (for lunch, for a lover, for lost time) might stand in for another.

Yet Fisher’s writing was also often marked by circumvention. The fifth chapter of The Gastronomical Me, “The First Oyster,” set during Fisher’s years at an all-girls high school in Northern California in the 1920s, chronicles a fraught yet fascinated series of engagements with the unsettling possibility of lesbianism. A recently hired gym teacher with “short and boyish” hair “has the most adorable little cracked voice, almost like a boy’s,” which causes such a sensation that by the end of her second week “three of the teachers were writing passionate notes to her.” The fact that two of the teachers are a couple is presented as straightforwardly as possible without actually using the word: “Miss Huntingdon [and] Miss Blake, her shadow, devoted, bewigged, a skin-and-bone edition of Krafft-Ebing”—the German sexologist and author of Psychopathia Sexualis, the 1882 study that introduced bisexuality, masochism, and homosexuality into English. Fisher is presented with her first raw oyster at sixteen during a holiday supper where she sits bracketed by older classmates, one of whom whispers in her ear immediately afterward, “Try one, Baby-face. It ain’t the heat, it’s the humidity. Try one. Slip and go easy.” The other—a senior named Olmsted, “the most wonderful girl in the whole school”—then asks Fisher to dance. Fisher accepts, unswallowed oyster sitting still in her mouth, “reeling at the thought of dancing the first dance of the evening with the senior-class president.” After a few dizzying minutes she is transferred to Inez, a junior Fisher immediately decides “was the most horrible creature I had ever known. Perhaps I might kill her some day.” She began to panic at the thought that all the other women in the room, teachers and students alike, are talking about how she “has the cutest ears,” certain that Inez is going to make a pass at her. Her writing begins to oscillate between bluntness and vagueness as she finds herself alternately intrigued and horrified. According to Zimmerman, Fisher had romantic relationships with both men and women throughout her life (Alex Prud’homme also makes passing reference to Fisher’s bisexuality in The French Chef in America: Julia Child’s Second Act), though Fisher makes sure to repudiate her own curiosity, at least in print, by the end of “My First Oyster.”

It is this strange blend of candor and evasion that characterizes two of the most jarring sections in The Gastronomical Me. Both moments take place in the book’s final chapter, “Feminine Ending,” written in 1941 by a thirtysomething Fisher. The episodes involve moments where Fisher outs someone living and working as a man under varying degrees of plausible deniability. She outs one fairly readily and one more reluctantly, and both involve an uneasy return to form afterward as an “open secret.” Both the chapter and A Gastronomical Me end in a literal ellipsis, a gesture profoundly aware of its own insufficiency, as Fisher declines to approach the most immediately relevant events—the sudden deaths by suicide of her husband and her brother in close succession—instead writing about another taboo subject, the transition of two men she scarcely knows. A book about eating, nourishment, and pleasure has no choice but to close on a note of hunger, uncertainty, and uneasy guilt. It’s an unsettling and unusual choice for the genre.

“Feminine Ending” is set during Fisher’s final trip to visit her brother, David, in Mexico shortly after her husband Dillwyn’s suicide and before David’s subsequent suicide a year later, in 1942. While Fisher draws a protective veil around Dillwyn’s and David’s deaths in “Feminine Ending,” she does write in close detail and at great, often speculative length about a mariachi singer named Juanito, whose relationship to David makes Fisher ill at ease. David insists on taking his sister to see Juanito’s band play one night, despite his new wife Sarah’s obvious discomfort, and needles Fisher with so many inexplicable questions about Juanito that she recalls the moment David orders a round of drinks as “really the only thing I understood in the whole conversation.” Subsequent run-ins with Juanito, who sometimes comes to the house to give David music lessons, are equally baffling. Fisher cannot bring herself to ask the relevant question: “Are you saying that Dave and this man are in love with…are having an affair with…I mean jealous of…” She chooses to continue floundering rather than risk landing on a more dangerous shore and openly naming even the possibility of homosexuality so close to home. In an unsettling transposition, Fisher details Juanito’s and David’s bodies with needling precision, calling attention to bone structure here, to hair color there, shading eyes and mouths and skin in lieu of naming the crisscrossing lines of desire, rejection, forbearance, and distress that mark their time together. She becomes newly and acutely aware of her family’s whiteness, particularly as it renders certain types of speech impossible: “We went there in our white skins…and lived among the courteous people of Jalisco as if anyone could live anywhere in such pale immunity.” The vague somberness with which she regards her family’s whiteness contrasts strikingly with the meticulous and patronizing tone she takes in describing Juanito’s “pale dirtiness…as if he slept in the dust,” eager to distinguish it from her own paleness. The chapter itself is a complicated morass of competing anxieties, desires, prejudices, and projections, as Fisher contends with a mounting sense of alienation from her surroundings, an increasing conviction that she ought not to be in the middle of her brother’s muddled, unhappy honeymoon, and that her family ought not to be in this Mexican village to begin with. She frequently wishes herself away from everyone and everything around her, alone in “a big white bed [with] nobody in the world to wait for.” Fisher’s acts of gender detection, both willing and unwilling, compassionate and repulsed, serve as temporary escape hatches from an otherwise incomprehensible muddle of family entanglements.

After mounting tension, David finally provokes Fisher into outing Juanito in direct conversation:

I felt bewildered and timid. If they already had the answer, why did they wait for my confirmation? Was I going to hurt anything?…I was full of little roasted birds and alcohol and a kind of heavy impatience with the world, so that when David said, “Well, what about Juanito?” I could hardly drag an answer through my lips.

“Well?” I said angrily. “Why ‘o’? Why this bluff? It’s Juanita, of course, feminine ending…‘a.’ ”

David laughed delightedly, as if he had pulled off some sort of coup, and I knew he had been boasting to Sarah, just the way Father might have, about the time I saw the woman at the job-press.

When she was a teenager Fisher’s father had taken her to his newspaper office, humoring her interest in the family business; she knew full well that he wanted to “save all that” for her brother David. He held her professional interest at arm’s length “because I was a woman,” and Fisher experienced that disparity keenly. Later that night, her father mentioned one pressman in particular as his best worker, Fisher erupted and “before I thought, I said, ‘But Father…that’s not a man! It’s a woman!”

Her father was at first disbelieving and angry, but later confronted the employee, who “stopped work for a few days, and talked to a minister, and after that [he] worked all week as a man, and then on Sundays [he] dressed in tailored dresses and went to church. I always felt badly about it, although the minister’s wife said things were much happier for [him].”

What might particularly strike the modern reader, who may have little sense of how people negotiated transition almost a hundred years ago in either Mexico or the United States, is the fact that both Juanito and the unnamed pressman return to their former male circumstances after a brief negotiation. The pressman strikes a Persephonic bargain whereby his job and gender role remain intact throughout the week so long as he attends church in women’s clothes on the weekend; Juanito returns to his band after a prolonged bender. This was not without precedent—Amelio Robles Ávila, a resident of the nearby state of Guerrero, lived openly as a man from the age of twenty-four until his death in 1984, serving as a colonel in the Mexican Revolution, for which he later received a Revolutionary Merit award and the Mexican Legion of Honor. Former neighbors recalled general social acceptance in later life, although Robles occasionally resorted to self-defense when strangers challenged his right to use his own name.

The Gastronomical Me’s closing lines deal with food only abstractly, focusing instead on a moment of identification and contrast between author and singer: “As Juanito sang the last bars to us and the weeping voices rose against [his] over the rhythm, I felt a kind of humility and a thankfulness that we were leaving. Juanito would be free again, as much as anyone can be who has once known hunger and gone unfed…”

Whether Fisher feels thankful to be leaving because she regrets something done or left undone, or because she feels implicated in having recognized something that depends on vagueness and disavowal, is unclear. Her anxiety for both Juanito’s and the pressman’s well-being is obvious, although her reluctance to go out of her way to help either of them is equally so. Her primary wish seems to be for distance, for an ability to cut the ties that might attach her to them, if only in her own mind.

David Lazar writes in his essay “The Usable Past of M.F.K. Fisher” that Dillwyn and David’s suicides “appear as shadows: dark tones and oblique allusion…Fisher later explained that she had never written about her tragedies because of a sense of literary decorum.” In a further act of circumlocution, Dillwyn appears not as Dillwyn in Fisher’s writing but as Chexbres, the name of a small Swiss village they once lived in together. Dillwyn underwent a leg amputation and chronic pain treatment as a result of Buerger’s disease; he died by suicide outside their home in Southern California in 1941. That Fisher would not wish to write directly about either her husband’s or her brother’s deaths is entirely understandable, but this absence sometimes makes “Feminine Ending” precarious reading. These deaths fall under the veil of Fisher’s decorum while transition, passing, and outing do not, which creates an implicit order of which subjects merit public acknowledgment (as long as that acknowledgment is accompanied by disavowal) and which require delicacy, demurral, and deference. Fisher’s relationship to gendered norms did not exist in a vacuum, and the complicated recollection of her split-second decision to out a stranger as a teenager was not necessarily driven by malice. Rather, as Jules Gill-Peterson, author of Histories of the Transgender Child, writes, “Materialist histories of sexuality and gender ask a key question: Why and how did homophobia, or transphobia, or a gender binary come to be? To what ends and interests?” People could and did transition in Fisher’s day, sometimes with tacit or even overt community support, although it’s unclear to what degree Fisher was aware of such things. Such transitions were often challenged and sometimes forcibly revoked, but in Juanito’s and Ávila’s cases, such aggressions were not insurmountable. Fisher finds it easier to question her father’s employee than her father’s sexist preference for her brother. Years later she prefers to scrutinize Juanito rather than the possibility of her own brother’s queerness, a specter she finds so unsettling she sputters into rare incoherence: “In love with…having an affair with…I mean jealous of…?”

Fisher published not under her given name, Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher, but with the initialism M.F.K. Fisher, a well-established authorial practice. During her life and afterward, biographers and critics offered a number of accounts for this decision, some of them directly contradictory. One of the most common and least frequently questioned explanations is that women authors publish under initialed names in order to deflect sexism, as Ruth Reichl claimed: “Fisher used initials deliberately; it was not easy for a woman writing about food to be taken seriously”—though why so many of Fisher’s male contemporaries and forerunners might do the same (T.S. Eliot, J.R.R. Tolkien, D.H. Lawrence, A.E. Housman, J.D. Salinger, H.L. Mencken, J.M. Barrie, and P.C. Wren, to name a few) is rarely considered in that context. In a 1998 interview with Fisher’s sister, Norah, Judith Moore offers a competing claim, that Fisher first “used her initials [because] she didn’t want her father to know she had written” a magazine story published in 1934. Victoria Burns suggests yet another possible reading of Fisher’s initial adoption in “Narrating (Dis)Embodiment in M.F.K. Fisher’s Memoir,” claiming that “The Gastronomical Me presents a disembodied protagonist who sidesteps corporeal and gender-specific implications of the sensory-driven, unapologetic eating she promotes.” Fisher was certainly aware of the frequent precariousness of her position as a woman writer and solo diner, and equally aware of her relative security in contrast with Juanito.

In the “Dining Alone” chapter of a later book, An Alphabet for Gourmets, Fisher writes, “I came to believe that since nobody else dared feed me as I wished to be fed, I must do it myself, and with as much aplomb as I could muster…Some much younger and prettier woman who had never read a recipe in her life…was for that very reason far better fed than I.” Fisher was not a woman like this young and beautiful construct but still safely a woman, with a satisfyingly feminine ending of her own. “About this time every year a small idea nags at my mind about how wonderful it would be to cut off most of my hair,” she writes in her Bareacres Journal, published posthumously in 1993. “It creeps into my other thoughts, and I find myself speculating willy-nilly on how it would look, feel, be. I always decide, because I know it to be true, that I had better leave well enough alone, and that I would regret it.”

If Fisher sees something of her own unfed-ness in Juanito or the pressman, she remains as reluctant to draw a straight line between them as ever. The attachment can be grasped only by implication, after the further passage of years, and never directly. Identification and distance, fascination and aversion, hunger and satiety, avowal and disavowal characterize these queer incidences, but always leaving Fisher on the safer side of the dividing line between those who eat and those who watch others eating.