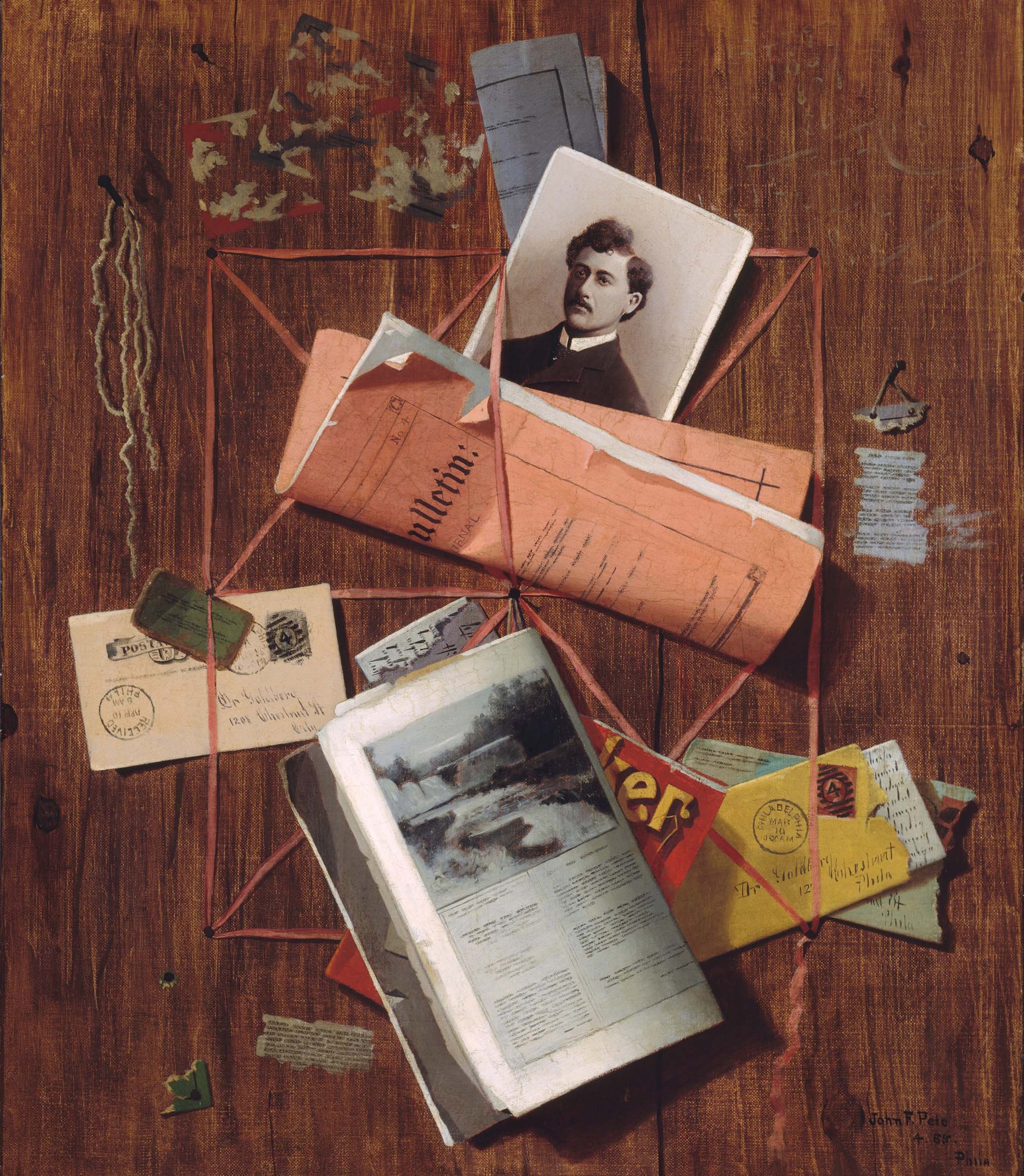

Office Board, by John F. Peto, 1885. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, George A. Hearn Fund, 1955.

The narrator in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time refers quite often to the text we are reading, naming “the invisible vocation which is the subject of this book” and “the rest of my story.” He even recalls the moment of what we can see as the hesitations of Proust’s unfinished book of essays, Against Sainte-Beuve: His “hopes,” he says, “were…doomed to frustration every time I sat down to a desk to sketch the draft of critical study or a novel.” Sometimes, “this book” still seems to belong to the future. All he has to his literary credit, he says, are “some very thin articles,” adding, on another occasion, that he has published “some studies.” He is probably being a little too modest here, in part because he is trying to show how wrong those people are who mistake him for a successful, even a great writer. And he has made some sort of start on his novel because he has shown it to a few people, who didn’t understand it at all. But then he also talks about what “the final volumes of this work will show” and says, “we have seen” what previous episodes have proved.

But who is talking to whom when we read these allusions to a novel in progress? As actual readers of Proust’s book, we have seen or read precisely these words and many others. But then is the fictional narrator speaking to us or to his fictional audience? Do we get a little dizzy thinking about his imagining as part of the past a beginning he hasn’t arrived at yet, or do we think Proust could just be making casual use of an old convention: the writer pretends she is telling a tale and readers pretend they are listening? The material acts of writing and reading are bracketed or forgotten.

When, in Bleak House, Esther Summerson writes of “my portion of these pages,” meaning that half of the novel which is not the domain of the omniscient narrator, do we really think of her physically writing, or do we translate her portion as representing her angle on the story, a fictional division that borrows a real division of style? When David Copperfield, similarly, wonders whether he is going to be the hero of “these pages,” do we linger over the actual volume in our hands and wonder if it is a duplicate of something David has written? There is only one book here, we might think, the one written by Dickens, and David is an employee, doing a familiar, first-person job. He is also, in case we have any doubts, speaking the unspeakable, as when he says, in the first chapter title, “I am born.”

I don’t think we should rush to choose between our answers since both have their attractions. The old convention allows us to settle into the fiction and not worry too much about the textual or epistemological status of the characters. The second offers us Esther and David, dizzyingly, as fictional characters who know they are in a real book, like Molly Bloom at a certain moment in Ulysses or Proust’s narrator when he casually drops his author’s first name. I am, I confess, much drawn to the second view, which I take as congenital (and congenial) to fiction and not as a postmodern trope. There are more of such games in Jane Austen, for example, than in most twentieth-century writers. It is, we might say, adapting an idiom from Proust, the Nabokov side of George Eliot. But I also like the idea of an untroubled enjoyment of literary illusion, and we can, I believe, allow ourselves both postures, although perhaps not at exactly the same time.

The two postures correspond precisely to the two major views of what it is we are reading when we take on In Search of Lost Time, that is, what role we assign to the actual work. An earlier consensus suggested that we are enjoying the very novel the narrator says he is about to start work on and will complete if he has time. It is not an accident (as they say) that the last sentence of the completed work begins with, “At least, if” and ends with “in Time.” The view is too simple and too smooth, but sometimes we need simplicity and smoothness. The chief problem with it, apart from many narratological hitches, is that it loses sight of, or buries, at least two other serious and moving possibilities: the narrator didn’t finish his book, he just got to the point where he thought he might; the book we are reading, in spite of many alluring invitations to the contrary, may be nothing like the work the narrator planned to write or could write.

A dizzying moment in the fifth volume plays with all these perspectives. The narrator thinks Charles Swann should have a little more respect for the book in which he was a major character, or at least be more grateful for the part the work played in the diffusion of his social fame:

It is…because someone whom you must have considered a little idiot has made you the hero of one of his novels that people are beginning to talk about you again, and perhaps you will live on.

This remark appears in the middle of a passage about Swann’s death, so the narrator knows he is addressing a ghost. Even so, it is a little odd for a fictional narrator to be addressing another fictional character as an immediately identifiable historical figure, and the strangeness continues:

If people talk so much about the Tissot painting set on the balcony of the Rue Royale Club, where you are standing with Gallifet, Edmond de Polignac and Saint Maurice, it is because they can see there is something of you in the character of Swann.

The painting actually exists, and a man called Charles is found there among the other named persons. He is the wealthy Parisian Charles Haas, the chief but not the only model for the character of Swann. We can, if we work at it, preserve some kind of realistic illusion here. The narrator, thinking of the fictional figure who has just died, looks far into the future when his as yet unstarted book is being read, and he registers the imaginary ingratitude he assumes will still be in place. Proust may be thinking here of Dostoevsky, who likes to play similar games with the status of fiction. In The Adolescent, the narrator says:

I am not writing for publication. I’ll probably have a reader only in some ten years, when everything is already so apparent, past and proven, that there will no longer be any point in blushing. And therefore, if I sometimes address my reader…it’s merely a device. My reader is a fantastic character.

The easier but still quite complicated interpretation turns to Proust himself and watches him playing games with his puppet narrator. The chronology in this view is perfectly coherent: the part of In Search of Lost Time called Swann’s Way was published in 1913 and a copy of the Tissot painting appeared in the magazine L’Illustration in 1922. The lines about Swann and the painting, the French scholar Jean Milly tells us, “are one of the last references to actuality introduced into the novel.” The suggestion is, perhaps, that Haas, rather than Swann, should be grateful, but he had died in 1902 (a little later than Swann, if we follow an accepted imaginary time scheme) so also would be able to fail to present only ghostly thanks. The accent falls the more heavily on the narrator’s injured vanity, his infatuation with the work he may never complete.

Adapted from Marcel Proust by Michael Wood. Copyright © 2023 by Michael Wood. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.