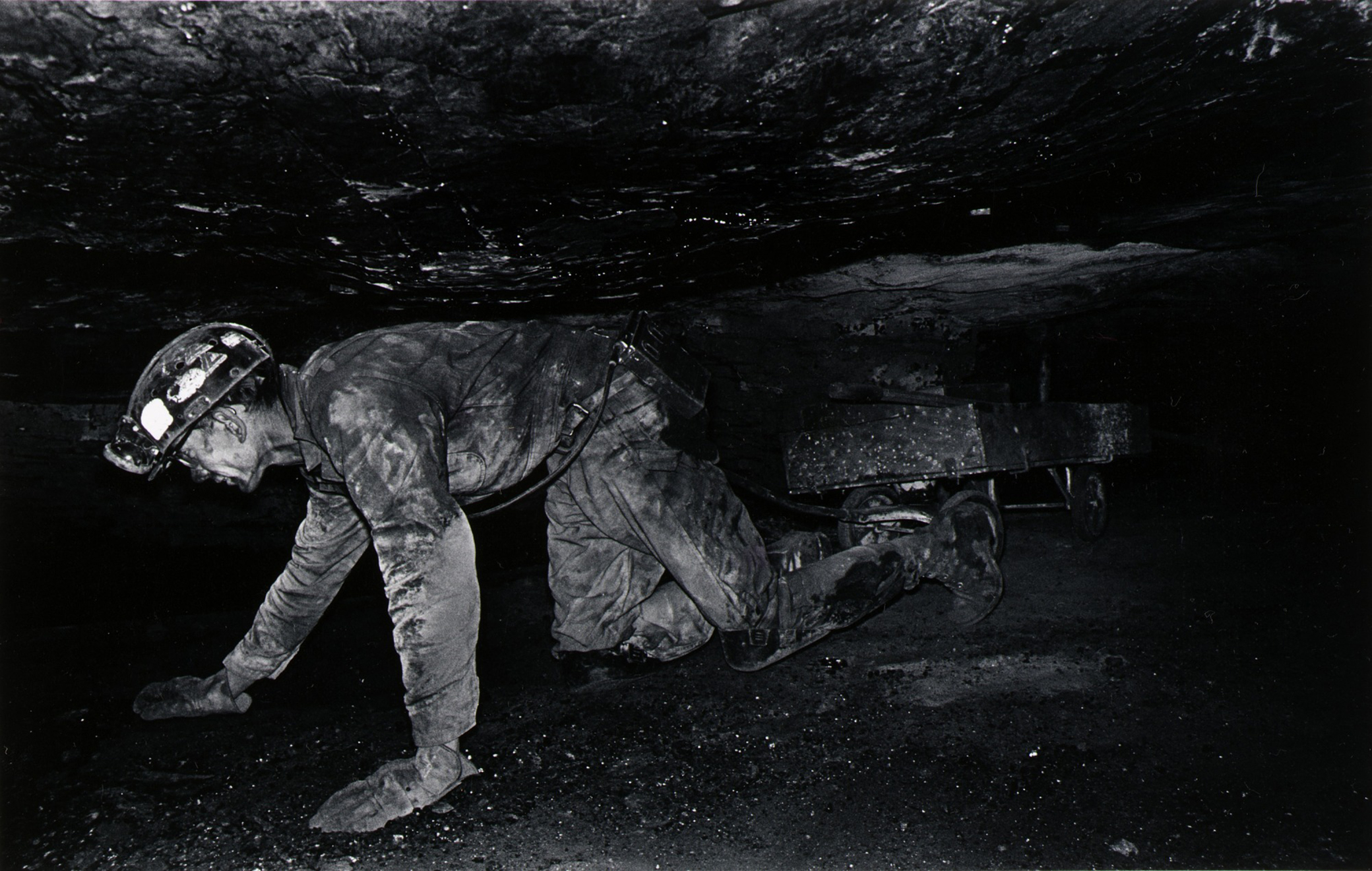

Appalshop, Inc., Documentary Survey Project, by Earl Dotter, c. 1975. Smithsonian American Art Museum, transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts, 1983.

Just before midnight on November 19, 1968, ninety-nine men working on the “cat-eye shift” at Consolidation Coal Company’s Number 9 mine walked into its bathhouse and began pulling on their thick work shirts and darkly smudged overalls. Superstitious, none of them dared call their 12 am to 8 am turn in the mine the “graveyard shift.”

They stepped into steel cages and started their nearly six-hundred-foot drop to the mine’s sooty floor. The oldest among them was sixty-two, the youngest only nineteen. They lived on narrow, pitching streets in little northern West Virginia mining communities called Idamay, Enterprise, and Shinnston. One had mined coal for forty-two years, another for just eight days. Many of the men on the cat-eye shift were veterans. By 1968 1,400 men from Marion County had fought in Vietnam.

When they reached the bottom, the miners broke into six- to eight-man crews and boarded mantrips—electric train–like vehicles that ran on rails or had rubber tires—that carried them through Number 9’s vast network of spidery tunnels to their workstations. For the next eight hours they would cut and load coal. One crew toiled at freeing a large piece of equipment that had been covered with slate and debris during a roof fall while the others clawed coal out of the mine’s rich seams.

But earning a living was not the only thing on their minds. They knew that the shift of miners working before them had had to stop digging three times, once for two and a half hours, while the mine’s four giant surface fans drew fresh air into its tunnels and diluted deadly methane gas.

They also knew that they were working at the most dangerous jobs in the country for a company that was obsessed with extracting as much coal as it could.

In 1963 The Atlantic called coal mining a “mortician’s paradise,” and for good reason. The federal government first began compiling statistics on coal-mining deaths and serious accidents in 1900, and by November 1968 over 101,000 coal miners had been crushed, gassed, electrocuted, or incinerated underground, while another 1.5 million had been seriously injured. Coal mining’s injury rate was four times higher than that of any other industrial job in the United States and fourteen times higher than the national average for all workers.

At least another 150,000 active and retired coal miners had pneumoconiosis, or black lung, contracted by inhaling coal dust, which made their lungs as porous as fishing nets and turned them into wheezing wrecks.

The Consolidation Coal Company and the reckless way it operated Number 9 had added to these grim statistics. In 1954 an underground blast killed sixteen miners working on a chilly Saturday in November. Some engineers argued then that the mine was too dangerous and gassy to reopen, but its coal deposits were too rich for its owners to abandon.

Eleven years later, a four-man crew was standing on a scaffold 233 feet inside the mine’s 577-foot-deep Llewellyn airshaft when a spark below ignited a pocket of methane gas. The four men were orbited up and out of the huge shaft’s mouth as if they had been shot out of a bazooka. Their shredded body parts were found later in a creek, seventy-five feet from the shaft.

Consolidation Coal Company simply wrote off these losses as the price of doing business. By 1968 it was the biggest bituminous coal producer in the country. Workers who complained about the mine’s poor safety conditions were ignored, and the coal company gave its loudest critics the most dangerous jobs.

The federal government’s attitude was no better. The United States Bureau of Mines had only 250 inspectors assigned to watch over the country’s 5,400 mines. They had fined only one operator in sixteen years. The bureau was a captive of the coal industry, and its managers fired or transferred inspectors who pushed too hard to close big mines.

Worse, the miners’ own labor union seemed to care more about its fat coffers than the men who filled them. The United Mine Workers of America had a one-man safety division. Its District 31, where Number 9 was located, spent only $14 on safety training in 1968.

The temperature at midnight on November 20 was a chilly 35 degrees. Coal operators dismissed it as hillbilly folklore, but every miner in West Virginia knew that the months of November and December were the explosion season. Cold air accompanied by dizzying drops in barometric pressure dried out mines and caused them to fill with odorless methane gas and mix with thick coal dust, whipped up by giant electric continuous-mining machines, with rotary bits as big as a railroad boxcar’s wheels. The faintest spark could turn this volatile mixture into something like gunpowder and transform a mine’s shafts into smoking barrels of underground cannons.

This had happened at Monongah, only seven miles from Number 9. On a cold clear day in early December 1907 an underground explosion inside the Fairmont Coal Company’s interconnected mines Numbers 6 and 8 pulverized at least five hundred men and boys. It likely killed a lot more; no one knew exactly how many newly arrived immigrants, mostly from Italy and Poland, worked in the two mines.

Number 9 burrowed into the same eight-foot-thick, gassy Pittsburgh coal seam as the Monongah mines. It emitted eight million cubic feet of methane gas a day, enough to heat a small city. The mine’s four towering surface fans, which ran around the clock, were supposed to draw enough fresh air into the mine’s tunnels to dilute and blow away this odorless but explosive gas, but they sometimes broke and shut down for hours.

At 4 am the men on the cat-eye shift took a short break to eat the packed food they brought with them in the mine’s “dinner holes” and rest.

Just as the men had stopped to eat, the Mods Run fan, one of the mine’s four huge surface fans, ground to a halt and threw off its blades. While the men ate, Number 9’s west-side tunnels began filling with deadly methane gas. Seventy-eight of them would soon be dead.

Number 9’s safety system was designed to warn its miners after a fan stopped ventilating. Each fan was connected to a display board in the lamp house, a building near the mine’s entrance used to store supplies. When a fan slowed or stopped running, a warning light turned red, an alarm sounded, and the men evacuated. As a fail-safe, the system was designed to cut off all power to Number 9 if a fan was down for more than twelve minutes.

That is, unless someone in the company decided that shutting off power and evacuating the miners interfered too much with cutting and loading coal. Sometime before the Mods Run fan stopped working, a coal company employee disabled the fan’s alarm system.

At 5:27 am an explosion so violent that it shook the windows in Fairmont twelve miles away tore through the shaft at the mine’s Llewellyn Portal. Billowing mushroom clouds, shot through with orange and blue flames, curled above the mine. The heat was so intense that it scorched several of the miners’ cars in Number 9’s parking lot. Thirteen men, working elsewhere in the sprawling mine, scrambled to the surface. A crane operator, using a makeshift bucket, extracted eight more.

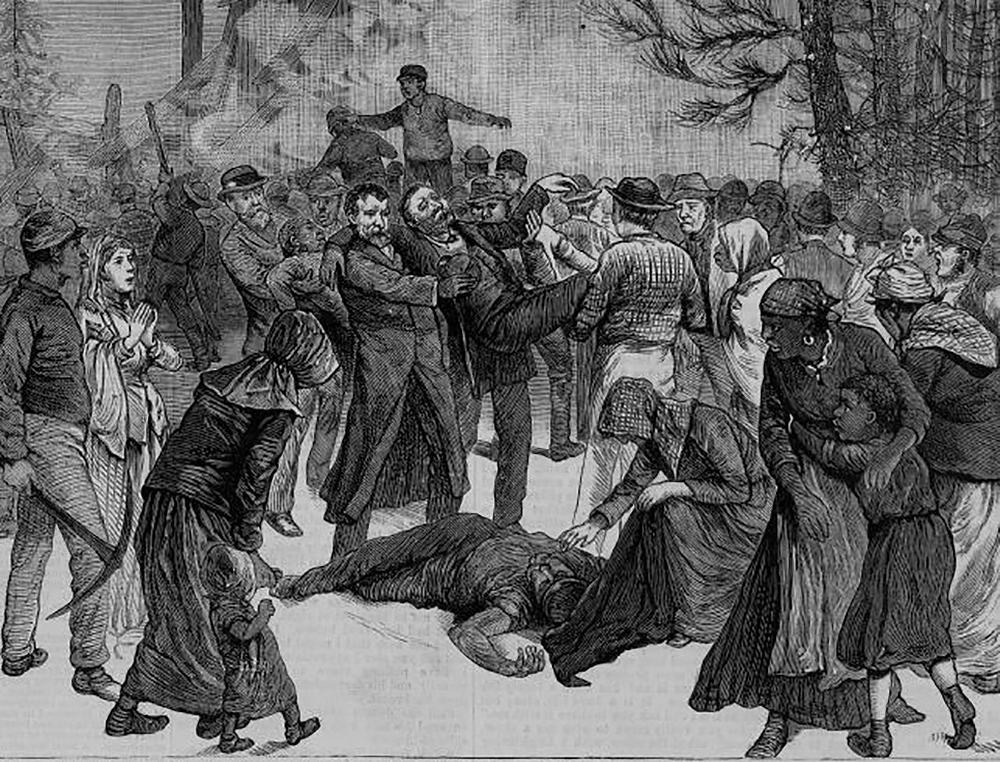

As the mine belched fire and smoke, word raced through the tiny Appalachian communities surrounding Number 9 that it had blown up. Family members, tears in their eyes, gathered in the mine’s cinder-block company store, clustered among its plastic furniture, and stared out at the rolling clouds of smoke. Some of the missing men’s wives were grandmothers, others were still in their teens. Those women who had experienced mining disasters before suspected the worst. They gave up hope of ever seeing their menfolk again and went home soon after they arrived. Others previously untouched by underground explosions clung to hope and waited for any news about a rescue.

The grisly drama of a shift of coal miners trapped in a burning hole a week before Thanksgiving attracted the country’s biggest dailies and news networks, making this the first major mine disaster in United States history to be nationally televised. While the first explosion had killed some of the miners instantly, others had enough time to put on their gas masks. Recovery crews later found an open first-aid kit and bodies lying on a sheet of canvas, as if some of the trapped men had lain down together to conserve their dwindling supply of fresh air.

The news cameras were still rolling when apologists for the coal industry trooped before reporters to circle the wagons. John Roberts, who headed Consolidation Coal Company’s public relations department, described the explosion as “something that we have to live with,” as did J. Cordell Moore, an assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of the Interior, and Hulett C. Smith, governor of West Virginia. Smith, who led a state in which there was more debate about whether there should be sex education in its public schools than about safety in its coal mines, lectured the grieving families that “we must recognize that this is a hazardous business and what has occurred here is one of the hazards of being a miner.”

But the most astonishing performance was that given by W.A. “Tony” Boyle, wearing his signature Washington uniform of a fedora, a pressed suit, and a red rose in his lapel. His few appearances in the coalfields were usually carefully staged, allowing him time to don a new pair of overalls and shiny work boots, but this time Boyle swooped onto the scene in a helicopter furnished by the coal company.

When he stepped up to the hastily erected podium in the company store, Boyle stunned many of those who had gathered to hear his expected words of sorrow and outrage by instead, in a flat, nasal voice, praising Consolidation Coal Company’s safety record and its history of cooperation with the union. He reminded the families, as if they did not already know it, that coal mining was a very dangerous way to make a living. The public spectacle of the UMWA’s president defending the grossly negligent, if not outright criminal, actions of a coal company while seventy-eight of his coal miners lay entombed in its burning mine shocked many of the onlookers. “I hated him right then,” Judy Henderson, now a widow at just twenty-one, told the Washington Post. “I couldn’t believe someone could say that right in front of the mine where all our husbands were buried alive.”

Many of the families clung to hope until the day after Thanksgiving. On the evening of Friday, November 29, when they gathered to pray inside the James Fork United Methodist Church, John Corcoran, president of Consolidation Coal, stepped forward and told them the time had come to seal the mine. He had already told a group of local ministers on Thanksgiving that there was no hope, but he had not wanted to give the families such awful news on the nation’s day of prayer and thanks.

The grieving families—235 children had lost their fathers and 74 women had lost their husbands in the underground inferno—had little reason to believe that this latest coal mining disaster would be treated any differently than all the ones that had come before it. The nation’s response to tragedies such as Number 9 had always been the same: prayers, an outpouring of sympathy for the widows and children, toothless coal-mining safety legislation, and a return to the collective amnesia that allowed things in the mines to go on as they always had.

Excerpted from Blood Runs Coal: The Yablonski Murders and the Battle for the United Mine Workers of America. Copyright © 2020 by Mark A. Bradley. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.