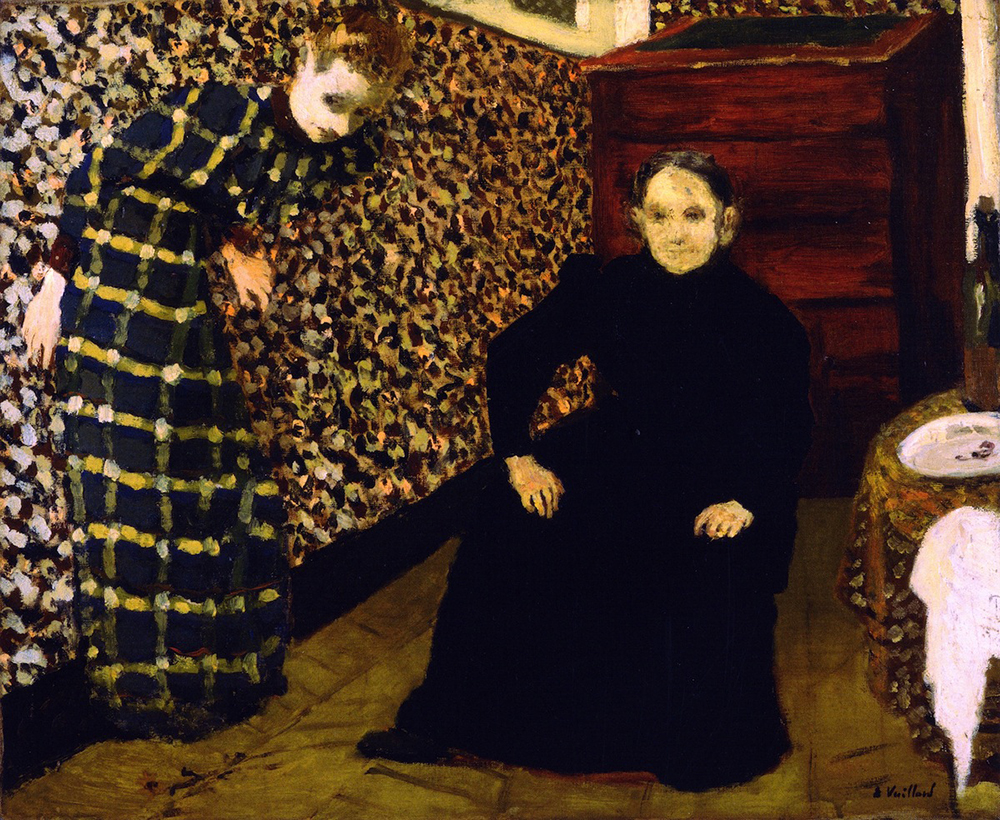

Mme Vuillard Sewing by the Window, rue Truffaut, by Édouard Vuillard, c. 1899. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975.

In 1864, having recently begun his new dramatic poem, Hérodiade, based on the biblical tale of Salome, the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé wrote to a friend, “I’ve invented a language that must necessarily spring from a new conception of poetry. I could define it in these words: To paint, not the thing, but the effect it produces.” One would be hard-pressed to find a more concise philosophical analogue to the work of Édouard Vuillard, whom Mallarmé greatly admired. (Indeed, Vuillard was his first choice to illustrate Hérodiade.) The French painter and printmaker shared with Mallarmé an oblique aesthetic in which the prosaic was wedded to mysterious abstraction. Vuillard’s cryptic interiors—beautifully muted rooms bathed in the afterglow of memory—comprise a private, dreamlike vision of domesticity in which uncanny atmospherics estrange the familiar. “No artist has ever so suggested the soul of an interior,” the German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe said of Vuillard, and that incorporeal leap epitomizes his finest work. Peering into these silent, half-lit dramas of habitation, we approach a singular, if often unsettling, intimacy. In the paintings of an Intimist, a room is never just a room, but rather, as Mallarmé had it, “the effect it produces.”

Intimism, a term first coined by French art critics in 1883, was a late nineteenth and early twentieth century aesthetic movement ostensibly concerned with small-scale domestic tableaux. It emerged from a fin de siècle Paris in which ambitious, heavily patterned decorative painting had achieved something of a vogue. The two most representative Intimists, Vuillard and his lifelong friend Pierre Bonnard, were first members of the Nabis (Hebrew for “prophets”), a short-lived but influential affiliation of artists who aimed to liberate color and form from l’art pompier, a derogatory term for the stiff academicism of painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel. The group began their meetings with a recitation: “Sounds, colors, and words have a miraculously expressive power beyond all representation.” From the japoniste woodcut stylings of Félix Vallotton’s languid L’Indolence (1896) to the flat, color-saturated river of Paul Sérusier’s The Talisman (1888), the Nabis sought the numinous in scenes taken from everyday life. After the collective disbanded in 1899, Vuillard and Bonnard continued to experiment in the realm of the everyday—in their case, fleeting domestic visions—creating a series of alluring interiors whose objects and inhabitants are alternately clarified and obscured by a kind of mystical subjectivity. Vuillard’s Misia and Vallotton at Villeneuve (1899) is emblematic of Intimism’s charming misdirection, a room that somehow manages to appear both crowded and confined to little isolations, a manipulation of emotional and physical space. The effect is mundane and metaphysical, lonely and strangely sociable, a canvas of lush conflict.

That name—Intimism—has done the two painters no favors historically. “Bonnard is almost a major painter, but not quite,” wrote the critic Clement Greenberg, expressing a popular mid-century assessment. Domestic intimacy was a diminished subject for the high prophets of modern art, an airless domain only one remove from undue sentimentality. At a glance, the well-appointed elegance of a Vuillard or a Bonnard composition can suggest just this sort of preciousness, a lightness of touch too easily dismissed as bourgeois idolatry. Picasso’s antipathy to the work of Bonnard in particular—“a potpourri of indecision,” he called it—is characteristic of much of the criticism leveled at Intimism: that it is too safe, too evanescent, an art of unreflective pleasures. (Picasso, it should be said, also loathed Monet; Bonnard finds himself in fine company.) Still, the question of seriousness lingers. Is Intimism, with its sensual color, languor, and wistful aura, merely a fringe of delicate foam on the wave of the avant-garde? Does it finally transcend the caricature of a fizzy, post-impressionist hangover?

As with much art, it depends on the looking. One wishes Picasso, for instance, would have considered the work more closely, and with greater care; perhaps he would have discerned not indecision but a rogue strain of modernism in which the domestic theater is amplified—or, in some cases, pared down—to the point of transformation. The French writer Camille Mauclair described Intimism as “a revelation of the soul through the things painted, the magnetic suggestion of what lies behind them through the description of the outer appearance.” This is the great and thoroughly modern truth the Intimists set forth in their work: that inhabitation is never less than equivocal.

The refulgent style of Pierre Bonnard, with its clotted, voluptuous color, can occlude such ambiguity. Its beauty gently lulls, casting a chromatic spell on the beholder, allowing the charged psychological moment to hide in plain sight, gathering momentum. The pleasure of the work acts as a kind of wondrous trap. Before Dinner (1924), one of more than sixty dining-room scenes Bonnard produced, is a fine example. The table, with its dazzling white cloth and gleaming accoutrements, initially draws the eye toward its lovely disorder, a still life caught unawares. But it is the two would-be diners perched along the edges of its orbit that create the painting’s particular intensity, a sense of interiors within interiors. The women are lost in reverie, looking anywhere but at us or each other. Like many of Bonnard’s hushed, reticent figures, they are in thrall to their own dreams. If there is a narrative here, it is indirect, suggestive, and finally ungraspable. (This Bonnardian quality has long been attractive to book designers; his paintings adorn the covers of classics ranging from James Salter’s Light Years to J.L. Carr’s A Month in the Country.)

His muse and companion, a former laundry girl named Marthe de Meligny, is the centerpiece to one of Bonnard’s most casually intimate paintings, The Bathroom (1932). The composition, with its bursts of spontaneous color applied in wayward, sometimes capricious brushstrokes, compels a gorgeous loitering. As we linger over the contrasting textures, ribs of braided color, and, most especially, that enigmatic figure at her toilette (Meligny’s face is rarely fully revealed in Bonnard’s work), a perceptible slowing of time occurs, a kind of incandescent idleness. Accretions of meaning form in these pauses, beautiful refusals to rejoin life’s proper velocity. To experience Bonnard’s Meligny paintings is to wait with the artist in an endlessly sensual interlude, one in which ambivalence is revealed to be a dimension of the erotic.

“He was an individualist without revolt,” Fairfield Porter wrote of Bonnard, “and his form, which is more complete and thorough than any abstract painter’s, comes from tenderness.” The same cannot be said for Édouard Vuillard, who, though only a year younger than his friend, seems to belong to a different school of art altogether—modern, yes, but of a particular modesty, a painter of hermetic, dreamy miniatures. Viewed beside the prismatic light and confectionary color of Bonnard’s larger canvases, Vuillard’s domestic vision, with its shadowed arabesques, cramped drawing rooms, and often faceless women, possesses neither tenderness nor the specificity of portraiture; rather, Vuillard is a poet of silences, of fleeting afternoon hours in which one can almost hear the patient ticking of a clock, a needle piercing cloth, distant steps creaking over lacquered boards. The human absorption that occurs between these sounds is his provenance—the rich interiority of preoccupation.

Still, as with Bonnard, the decor of Vuillard’s rooms is what we notice first (and what we must move beyond in order to encounter the strangeness waiting at the work’s core). The delicate, almost pointillistic surfaces of his wallpapers, tapestries, dresses, rugs, and upholsteries borrow from the Japanese ukiyo-e prints that had captured the Parisian imagination of the time. It would be a mistake, however, to see only exaltation in such motifs; it was also in many ways a tic of frustration. “In the most ordinary interior, there’s not an object the form of which doesn’t have an ornamental pretension,” Vuillard wrote in an 1894 journal entry, “and most of the time the form hides its function from us under these irrelevant embellishments.” In the claustrophobia of such works as Interior with Work Table (1893) and Interior, Mother and Sister of the Artist (1892), one discovers an almost tentacular patterning, the menacing extension of which seems to constrict the room (albeit very beautifully) and starve it of air.

The most consistently interesting inhabitants of these cramped chambers are women, unposed figures caught, unknowingly, in a shimmering limbo. These are not the women of Edward Hopper, gazing dreamily from windows, lonely, alienated, lost in the absorption of the outer world. Rather, Vuillard’s women are fundamentally interior creatures, taking tea, receiving visitors, sewing quietly. It is difficult to imagine them outside of their various rooms; like fish removed from water, one feels they would merely gasp in the foreign elements of bustle and light. Their mystery is adumbrated, curiously, by their normality. Interior, Madame Vuillard and Grandmother Roussel at L’Étang-la-Ville (1901), for instance, seems to catch the women between words, ensnared in a comfortable, conversational pause. They are bent toward each other, the fringe of a garden visible through the open window. We, too, lean closer, imposing upon their privacy both with voyeuristic pleasure and curious shame. We realize, with a pang, that Vuillard will bring us no closer. “It is due to him speaking in a low tone,” the French writer André Gide wrote of this curious effect, “suitable to confidences.” These confidences, though, sometimes feel like failed concealments—if much is suggested, nothing whatever is made explicit. Compared to, say, Henri Matisse’s Large Interior, Nice (1919) with its luminous clarity and confident central figure—a woman who, staring boldly out at us, seems to renounce the yoke of subjecthood—Vuilliard’s rooms bear a curious resemblance to the dusk of personal memory: potent fragments, half-submerged and ringing with absence.

“Dreams are brief, meager, and laconic in comparison with the range and wealth of dream-thoughts,” Freud believed. In dream, the image—no matter how banal—is multivalent, a merging of associations. In the interiors of the Intimists, something similar is at work, an aesthetic of condensation and displacement. A drawing room is also a mood, a fantasy, a chimera. It is a Proustian gambit, an idyll. It is, above all, a suggestion—that in meditating on the ordinary, one is sometimes granted a glimpse of the sublime.