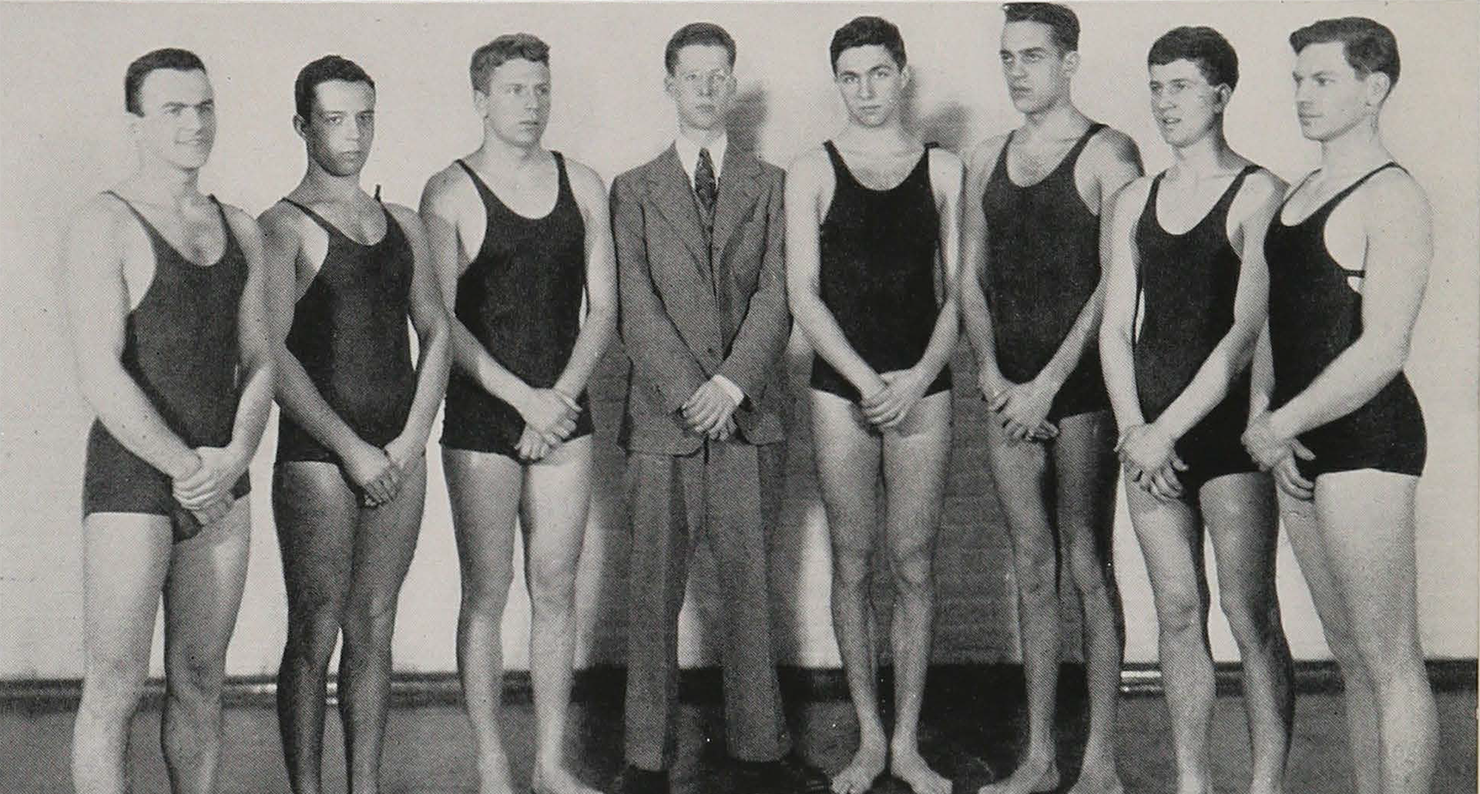

The 1938 Johns Hopkins swim team, with Murray Kempton (in suit) in center, from The Johns Hopkins Hullabaloo. Ferdinand Hamburger Archives, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.

Murray Kempton delighted in language. His readers did not always extend the same courtesy to his attempts to manipulate it.

“His ‘literaryness,’ said the Trotskyist New International in 1955, “in which the maudlin and the rococo march hand in hand, frequently results in clouding ideas and exaggerating the trivial to unwarranted importance.” The journalist employed “so many elegant British double and triple negatives, half the time you couldn’t figure out what he was saying,” groused Tom Wolfe, a pot with scarcely the right (to use a Kemptonian phrase) to call a kettle black on matters of elaborate syntax.

Kempton’s flourishes and asides weren’t aesthetic props, however; even his most gilded sentences sought, as if against themselves, to deflect attention away from the writer and toward the objects of his concern. What concerned him most consistently, from the editor’s desk of the Johns Hopkins University News-Letter in the late 1930s through the staff post at Newsday he retained until his death in 1997, were affronts to dignity mounted against the little people by the powerful, especially from the sides of management, the Pentagon, Jim Crow, and McCarthyism. He was one of the first white reporters to give serious attention to what would become the “classical” phase of the civil rights movement. His sympathies added leaves to his file at Hoover’s FBI but also earned him the early confidence of people like the president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, better known as Martin Luther King Jr., who wrote him in April 1956 to commend his “excellent articles” on the bus boycott.

Each of Kempton’s two book-length works took up the defense of radicals at precisely the moments when their reputations were lowest: the Black Panther Party in The Briar Patch (1973) and famous Depression-era communists in Part of Our Time (1955).

Today, Kempton no doubt reads purpler than ever—a quality that, paired with his immense generosity, may indeed suggest a certain moral cloudiness and a romantic, even patronizing treatment toward those subjects he admired most. His style could abet a tendency to elevate the drama of a character, whether Emmett Till’s uncle Mose Wright or Richard M. Nixon, to such heights that left only him with the oxygen to convey it in the language he thought it deserved. Seen another way, his journalism hazards a far-reaching empathy informed by the knowledge that there are no perfect victims nor perfect victimizers, and that, as the chant goes, the whole damn system is guilty as hell. (His derision could be cosmically withering: “We are assured that God does not make trash,” he wrote in 1989, “which thought disposes of the impression that Donald Trump is not altogether a self-made man.”)

This year marks a full century since Kempton’s birth and twenty years since he died in New York City, where he spent his career working for various papers, including the Herald-Tribune, the Post, and Newsday, and for magazines like The New Republic and The New York Review of Books. New York became Kempton’s city as completely as H.L. Mencken’s was Baltimore, where Kempton grew up. After graduating from “the Hopkins” in 1939, he moved to Manhattan for good.

Because Baltimore has such a tradition of shedding talented sons and daughters to New York, from Babe Ruth to Billie Holiday, what follows is a reclaiming of sorts, or a homecoming, to see what insights might out themselves by following Kempton’s observation that “a man’s childhood can condition him more than a law of history or what he conceives as the logic of his time.” In each of these houses lived a person whose life intersected with Kempton’s in an important way.

And never mind that Murray Kempton was born in Pennsylvania: Poe wrote “The Raven” in Philadelphia, and Baltimore named its professional football team for him anyway.

8 East Preston Street: Murray Kempton’s House

“I don’t remember ever hearing anyone at Eight East Preston Street say outright that to have suffered a misfortune was to have committed a trespass,” Kempton wrote in his unfinished memoir, “but no one needed to; that sentiment could no more have commanded the household than if it had been written in letters of flame on the living room wall.”

The inaugural misfortune of James Murray Kempton’s life came in 1920, when his father died of influenza near the end of the great pandemic. Kempton was three. From Philadelphia, his mother Sally Ambler Kempton returned with her family to the house on Preston Street that belonged to her father. It was there, “an outpost of exile from a Virginia where gallantry had insufficiently prevailed,” that little Murray grew up: “The world of shabby gentility is like no other; its sacrifices have less logic, its standards are harsher, its relation to reality is dimmer than comfortable property or plain poverty can understand.”

His great-grandfather John Magill Randolph had been Robert E. Lee’s chaplain during the Civil War. Another ancestor, James Murray Mason, served as the Confederacy’s ambassador to Great Britain and authored the Fugitive Slave Act, a pedigree that brought his great-great-grandson and namesake no small amount of embarrassment. So steep had the family’s fortunes declined that Sally Ambler took to working the sales floor at Hutzler’s, the temple of Baltimore retail on Howard Street. She was the only one of Kempton’s schoolmates’ mothers who worked. Around the corner lived the Warfields, whose daughter Bessie Wallis married the King of England only to become not a duchess but a kind of international paragon of shabby gentility.

Preston Street stifled Kempton. “We lived insulated by our history and surrounded by its memorials…I grew up in a home suffused with memories unvaryingly unreliable,” he wrote.

1524 Hollins Street: H.L. Mencken’s House

About the house on Hollins Street where he lived his entire life and died, asleep in his bed with the radio on, Mencken once wrote: “It is as much a part of me as my two hands.”

Kempton grew up reading Mencken every Monday in “the Sunpapers,” as they used to say in Baltimore. At age nineteen he got to witness Mencken in action while “blessed with a job carrying telegraph copy for Western Union” at the 1936 Democratic Convention in Philadelphia. Mencken was by then already becoming brittle in his prejudices—chief among them a neurotic contempt for Franklin Roosevelt—but the Sage of Baltimore could still dazzle.

The two reporters only ever spoke to each other a few times, but Mencken’s mark on Kempton could never be rubbed off, nor his ghost ignored.

There was a Mencken worth saving, Kempton wanted to believe—a Mencken that had to be salvaged from the reactionary cynicism and vulgarity of “followers drawn to the frozen model of his manner rather than the warm example of his intelligence.” This was not the Mencken whose Jew-dar ran hot and who praised Mussolini, but the Mencken who raised his pen in defense of Sacco and Vanzetti; who loathed the Klan and published Zora Neale Hurston; the Mencken whose mockeries punched up at hypocrites and confidence men of the cloth and the Capitol; the Mencken who could not cross the Chesapeake and pass safely through Maryland’s Eastern Shore for his stand against lynching.

But Mencken contained too much to be moved from where he fell—a whale, as Kempton figured him for The New York Review of Books, beached by his own contradictions. In the fifties, when the first director of Inherit the Wind solicited Kempton’s thoughts on Mencken, Kempton confessed “to thinking of him with idolatry, and it is idolatry’s worst defect that the idolator molds his idol from the clay of his personal prejudices.”

1330 Argyle Avenue: Pauli Murray’s House

Pauli Murray could remember the house where she was born in 1910 belonging to “a well-kept neighborhood of rising young professional people of color who were buying their own homes and paying ground rent to the City of Baltimore for the land on which their houses were built.”

Murray lived on Argyle Avenue only until the age of three, when her mother died of a cerebral hemorrhage and her father, mentally ill from typhoid, could no longer care for her. She met Murray Kempton in 1940 because of a black sharecropper from Gretna, Virginia, named Odell Waller.

The undisputed facts of the case were that Waller, twenty-one, had shot and killed his white employer, Oscar Davis, following an argument over a quantity of grain that Davis owed him. A jury of white farmers found Waller guilty and he was sentenced to death. Both Murray and Kempton worked to save Waller’s life—she as a twenty-nine-year-old advocate from the Workers’ Defense League and he as a twenty-two-year-old reporter. To generate publicity for an appeal, Murray and Kempton cowrote a pamphlet called “All for Mr. Davis” that argued Waller’s confession of self-defense and excoriated the poll tax and the feudal exploitation underlying Virginia justice: “It is a whole way of life for a disinherited people that flings its challenge to us, daring us to practice democracy as well as to preach it.”

Despite their efforts, the state executed Waller by electric chair in July 1942. For Murray Kempton, following Pauli Murray’s lead provided some of his earliest direct exposure to the stakes of reporting and could only have further diluted the myths of his post-Confederate childhood. The execution spurred Murray to pursue a law degree at Howard University, where she graduated at the top of her class and would have continued to Harvard had they not rescinded her scholarship after discovering she was a woman.

In 1950, the year Murray published The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment, she visited her old home in Baltimore to find “1330 still retained features of its original structure, and the woman who then lived there allowed me to walk through the six-room house and identify the front upstairs bedroom where I first saw life.” When she returned next, in 1980, it “had become a grimy slum…and the half-blind woman who lived in the house was the victim of an absentee landlord.” Today, the house is gone along with the rest of the block, which had long been vacant before its demolition.

“I shouted with joy when I read that my co-author of ‘All for Mr. Davis’ had won the Pulitzer Prize,” Murray wrote Kempton in 1985. “Bravo! Bravo! to a brother Baltimorean and member of the Murray clan!” The two of them had not kept in touch; she informed him that she had been ill, but now was gaining weight and able to write. Only two months later she died of pancreatic cancer, the same kind Kempton was diagnosed with the year of his death. “Just know that while we may not communicate with old friends,” she reminded him, “we do not forget those of our youth with whom we have fought together for unpopular causes.”

1427 Linden Avenue: Alger Hiss’ House

The enterprising child Alger Hiss raised pigeons, as a number of people in Baltimore still do. He sold some of them for squab meat. He also pulled his little wagon from Linden Avenue up to Druid Hill Park and filled bottles of water from the springs there to sell to neighbors. “Baltimore people didn’t think they had very good municipal water,” the adult Hiss explained in August 1948 to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The obscure detail of the bottling mattered to the Committee only because it corroborated something a senior editor at Time magazine, Whittaker Chambers, had said under oath a week before.

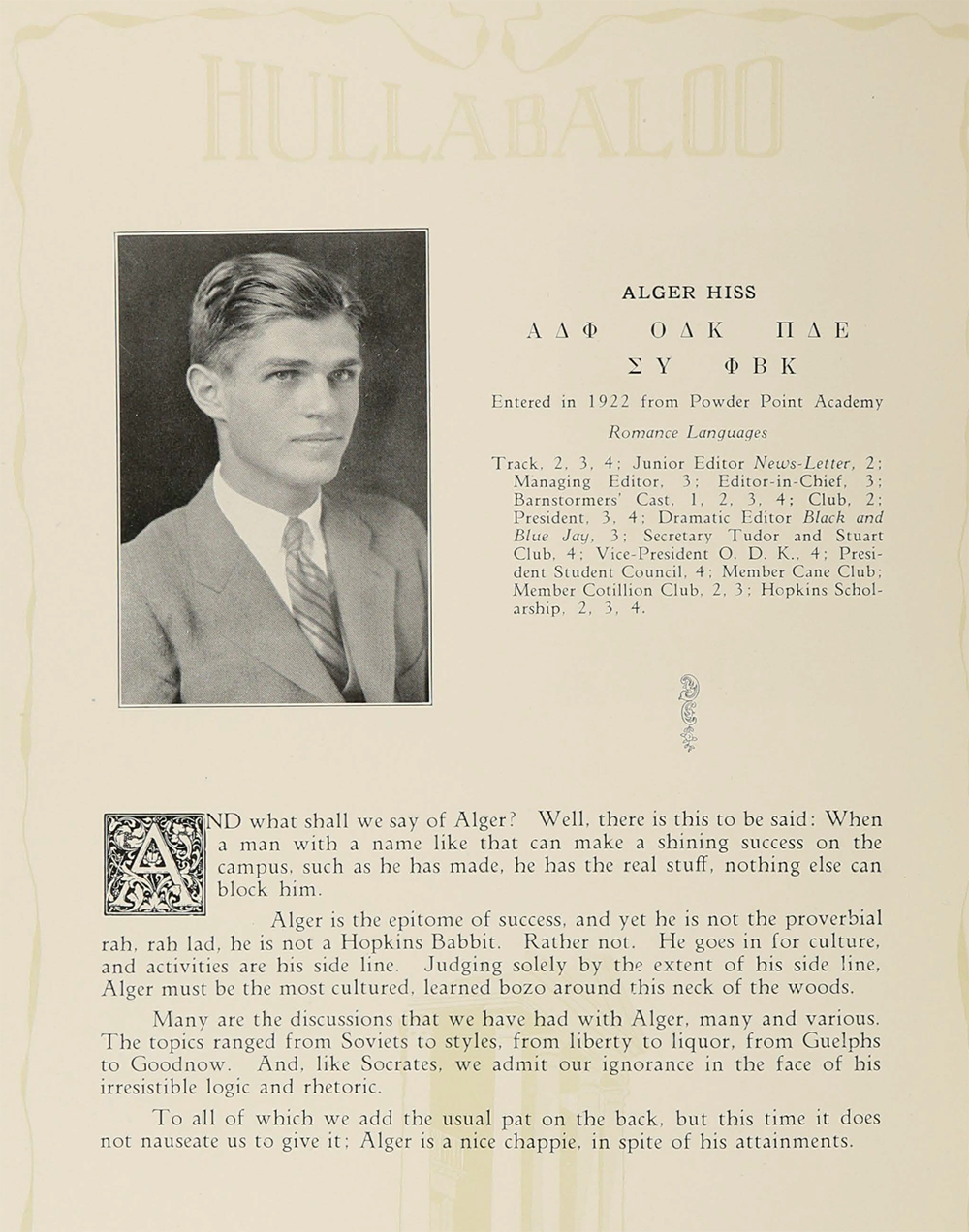

“And what shall we say of Alger?” begins his entry in the 1926 edition of Hullabaloo, the Johns Hopkins University yearbook. “Well, there is this to be said: When a man with a name like that can make a shining success on the campus, such as he has made, he has the real stuff, nothing else can block him.”

For twenty-two years, little else did block “the rising son of Lanvale Street”—as Murray Kempton incorrectly described him—from Hopkins to Harvard Law, the lower rungs of the New Deal’s brain trust, the State Department, the bargaining table at Yalta, the establishment of the United Nations, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. And then the moist, penitent Chambers volunteered to HUAC his memory of Hiss talking up his childhood springwater business, and many more memories besides.

As with Mencken, Kempton never knew Hiss but offered himself as a pro bono cryptographer of Hiss’s mind, enciphered as it had been by the same specific, class-anxious upbringing in Baltimore as his. In Part of Our Time, Kempton approached the question of Hiss’ having been a communist not forensically, as measurable by the evidence on paper (which he granted was clear enough), but with concern for the “inner mystery” of what motivated Hiss to very probably serve the Soviet Union and—“the last and deepest mystery”—why he continued to maintain his innocence. Kempton knew enough to speculate why the international proletarian struggle would attract a boy of shabby gentility, because he knew why he himself had been attracted to it. He knew it as sure as he knew what it was like for Hiss to have edited the Hopkins News-Letter, because he had done that too.

3955 Greenmount Avenue: Afeni Shakur’s House

“Everything changed in Baltimore,” Afeni Shakur told her biographer. “Everything.”

In another life, before Greenmount Avenue, Shakur had been a leader of the formidable Harlem branch of the Black Panther Party. With her comrades in “the Panther 21” she had beaten charges of conspiring to launch a campaign of bombings and police assassinations across Manhattan. The next month, June 1971, she gave birth to a son, Tupac Amaru.

By 1984, the year of Ronald Reagan’s reelection, Shakur was hostage to the comedown of the revolution deferred. She lost her job at South Bronx Legal Services, which she supposed had something to do with her ex-husband, Mutulu Shakur, an acupuncturist then on the run for his role in the 1981 Brink’s armored car “expropriation.” With no money and two children, she came south, to the house of a relative on Greenmount Avenue. “All my friends, my associates were gone, incarcerated, dead, underground,” she said. In Baltimore, she began again.

Kempton reported the proceedings of the Panther 21 trial for The Briar Patch, which won a National Book Award in 1973. The editorial standards for reporting on the Panthers had always been low in the white press, on the one hand overreliant on police sources and on the other frivolous in the manner of Tom Wolfe’s “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s” (in which Kempton figures minorly). Kempton helped fundraise on the Panthers’ behalf, but his most welcome intervention was simply to depict Shakur and her codefendants as people, insistent on their dignity in the face of the much larger and realer conspiracy set against them.

“Murray Kempton was there every day in that courtroom,” Shakur recalled. “God bless him.”

Afeni Shakur and Murray Kempton were not close, but he watched as Tupac’s star rose in the early 1990s, and then as Tupac stumbled and died. The writer appreciated the loss of Shakur for what it was, unlike much of the white press (“Tupac Shakur, 25, Rap Performer Who Personified Violence, Dies,” read the New York Times headline). His obituary for Newsday looked back to Afeni: “For all she knew she might be in prison for 20 years, and still she chose to have her baby,” he wrote. “He was a chosen child and a testament to a faith no less noble for having a reward no better than this.” Kempton could never have known that during Tupac’s time as a pupil at the Baltimore School for the Arts, one of his girlfriends happened to be the daughter of two local leaders of the Communist Party, and for a time the future “Makaveli” ran with what passed for the Young Communist League in the city, just as Kempton had in the days of the popular front.

It’s tempting, in this epoch of out-of-touchness in the media, to look with longing on the example of Kempton’s engagement with his times and the places he loved and left behind. He would be the first to discourage this, and to grant that on many counts history has judged him wrong. But especially in his attentiveness to irony and in his commitment to see and hear the story for himself, his voice serves to remind that “objectivity” is an ideology as befogging as any other, and that there are prospects for justice in our time better serving of common decency than even the benevolent designs of liberalism. A few years before his death, Kempton (“an inscribed socialist,” as William F. Buckley Jr. once introduced him) confessed to an interviewer his admiration for Edmund Burke—not for Burke’s conservative philosophy but for his “eye for the specific,” he said. “I mean the Burke who knew that a government that cut off Marie Antoinette’s head was not going to turn out all right.” Getting the specific right was attainable—reporters help to do that—but the general? He shrugged. “Who’s ever right in the general?”