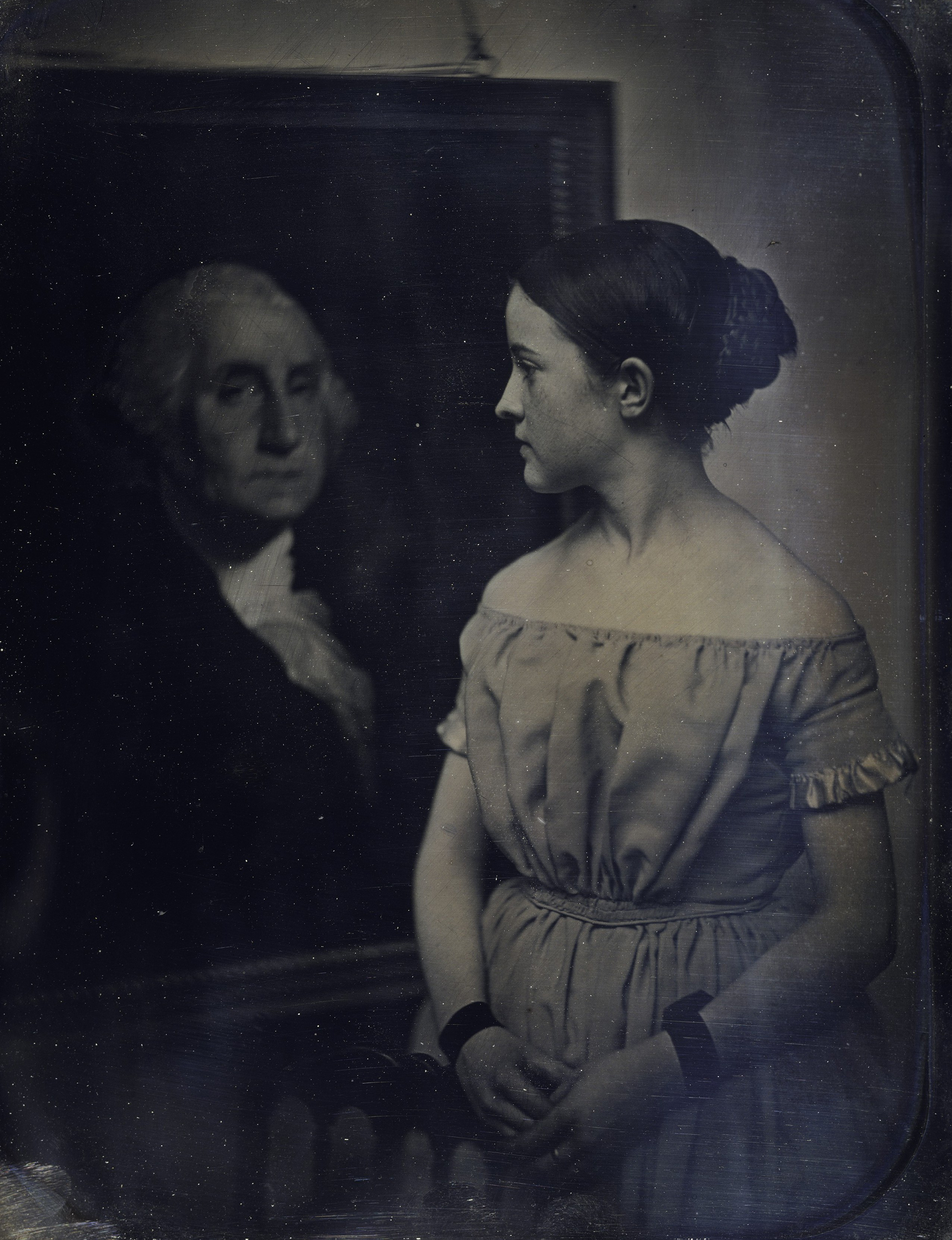

Girl with Portrait of George Washington, by Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes, c. 1850. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, and Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937.

In the centuries since the advent of the printing press, there have surely been myriad instances in which names like Ulysses S. Grant, Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, Julius Caesar, and William Henry Harrison were printed in considerable proximity to one another, and those, in turn, printed within striking distance of names like Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Anton Chekhov, and Johannes Brahms. It is only in the present and recent past, however, that one might find all those names closely juxtaposed in a roster with a title like “Sexiest Guys We Studied in AP History Class, dot Tumblr dot com.”

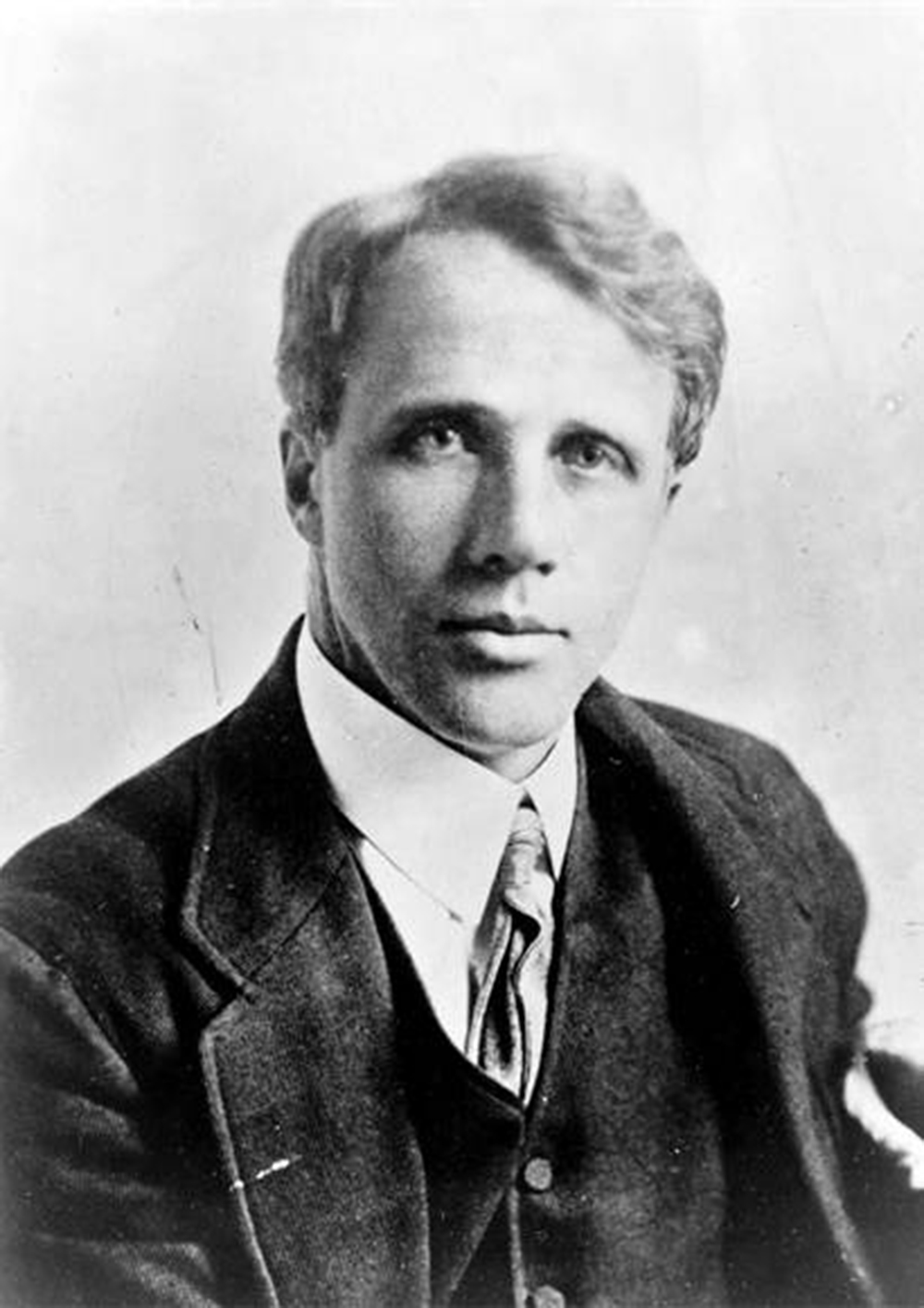

Writer Kate Dobson remembers sitting rapt in eleventh grade the day her English class studied the World War I poet Rupert Brooke, who seems from portraits to have looked like a composite of every well-known male English romantic-comedy lead of the 1990s. Twenty-seven-year-old Zoe Toffaleti had a similar experience in high school; she and a friend developed what she describes as “a serious crush on the ten-dollar bill” the first time they gave it a good look. Toffaleti went on to start the Tumblr Historical Hotties, whose tagline is “Guaranteed to improve your AP History scores.” Dobson cofounded the website Hottest Heads of State and cowrote the book Hottest Heads of State, Volume One: The American Presidents with her husband J.D.

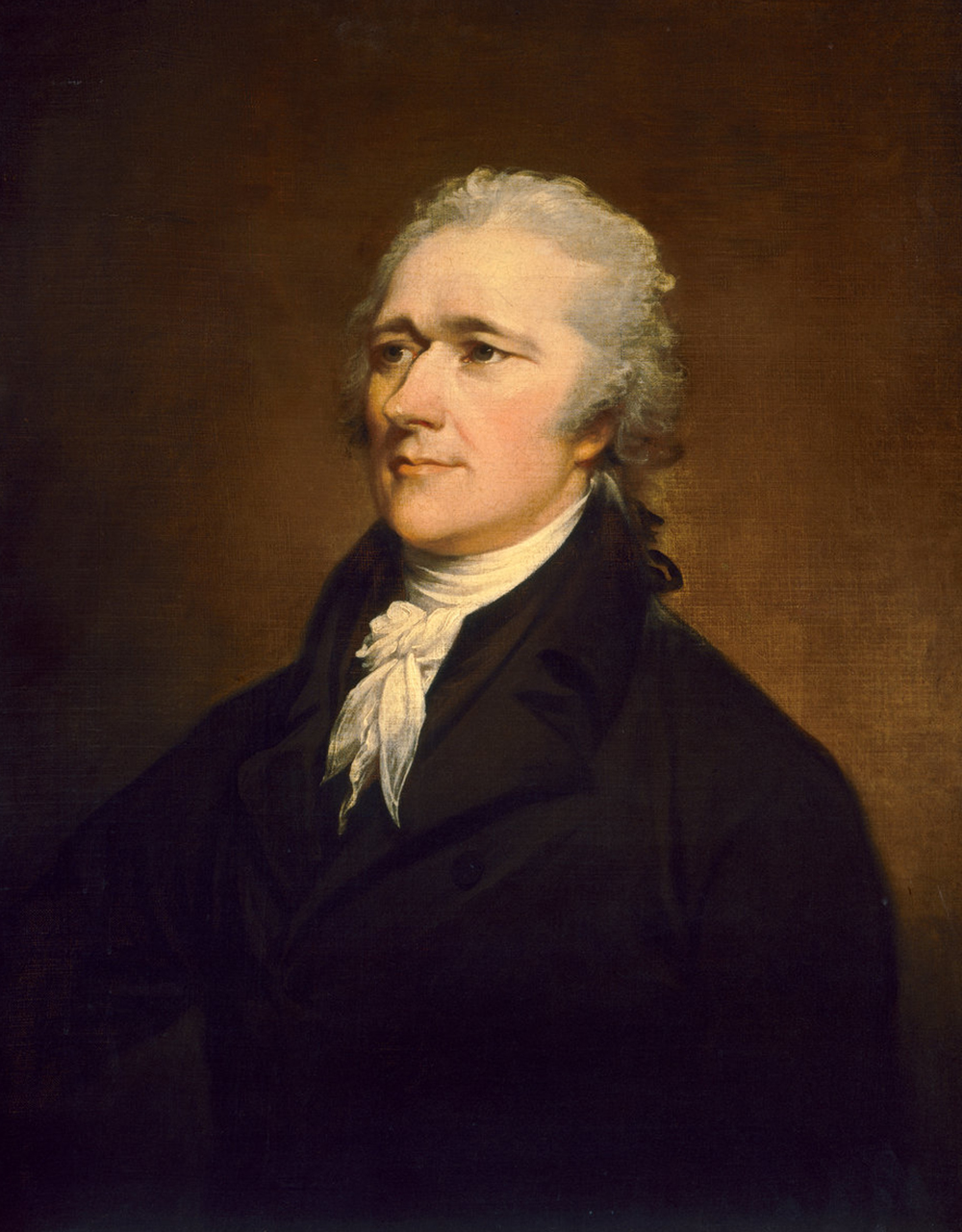

For as long as there have been physically beautiful famous people, portraits memorializing said physically beautiful famous people, and people who look at those portraits of physically beautiful famous people, there has existed the strange phenomenon of posthumous lust or attraction to dead historical figures, be it tongue-in-cheek or obsessively serious. But only in recent years has it become a widespread sensation, and it’s largely thanks to Alexander Hamilton and—in a development the computer engineers at ARPANET surely foresaw and endorsed—the internet.

Countless studies have shown that attractive people have an easier time getting jobs, raises, and election victories than their less attractive counterparts. A person famous or successful enough to have been immortalized in portraits or biographies, then, statistically speaking, would probably be on the attractive side. But the seemingly evergreen amusement at famous historical figures who were good-looking suggests a certain acceptable range of attractiveness for historical figures. Perhaps we prefer our great leaders and thinkers to fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum between tolerable-looking and outrageously hot.

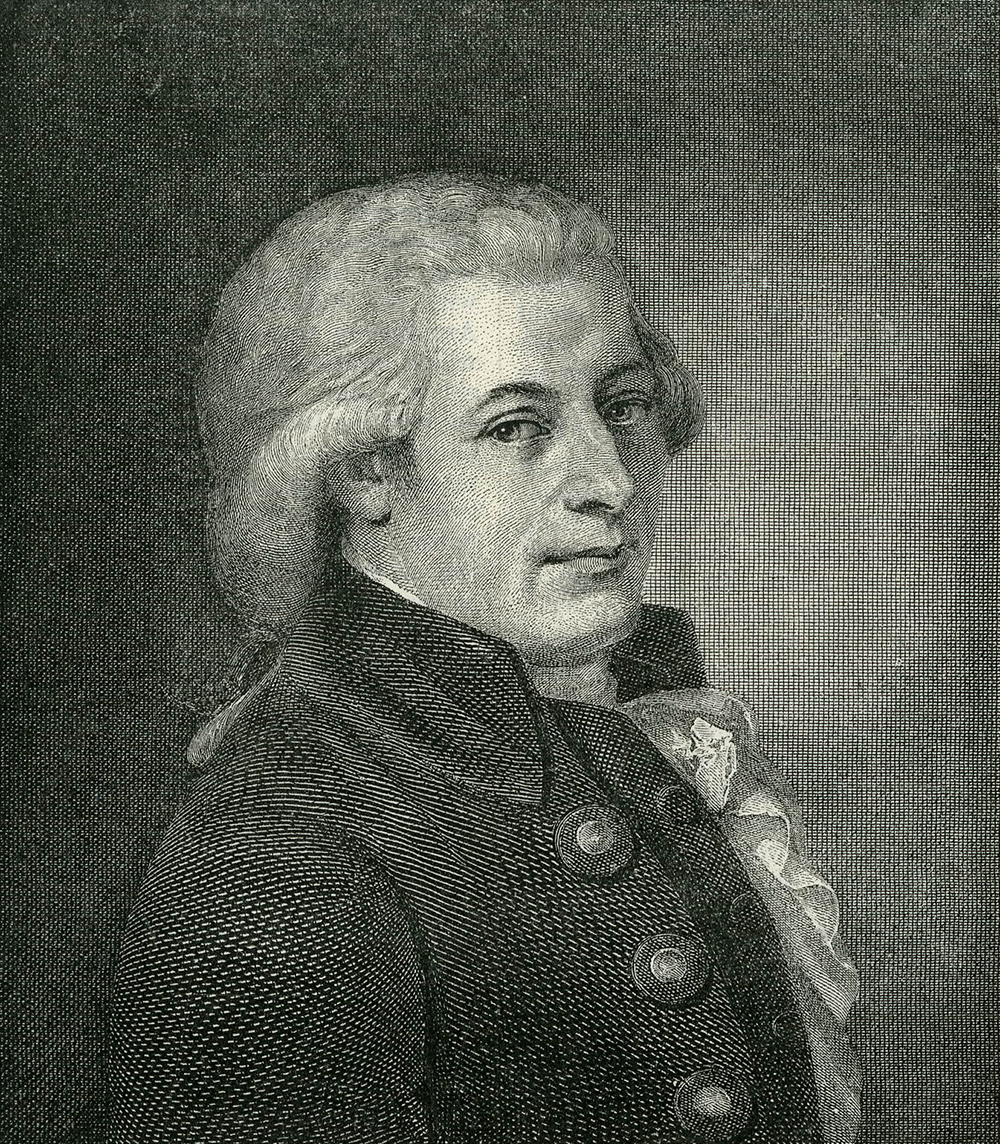

By the United Nations’ International Telecommunications Union’s estimate, the mainstreaming of the internet took place in the mid-2000s; the ITU’s data shows that the percentage of people in developed countries with access to the internet made the crucial leap from less than half to just slightly over that between 2003 and 2004. And naturally, by 2004, people were lusting over dead historical figures online. On forums like Hot Dead Guys and Historical Love on LiveJournal and Bangable Dudes in History on Blogspot, users would log on and share portraits of the long-dead geniuses they felt deeply for: Mozart, Napoleon, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Jefferson, Oscar Wilde, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, to name a few. (A sample entry from 2005, alongside a picture: “My personal favorite, though perhaps not for everyone: the Emperor Meiji. I have a thing for pensive eyebrows.” Meiji was the ruler of Japan until his death in 1912.) And on many of these blogs’ introductory pages is the striking visage of the United States’ first secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

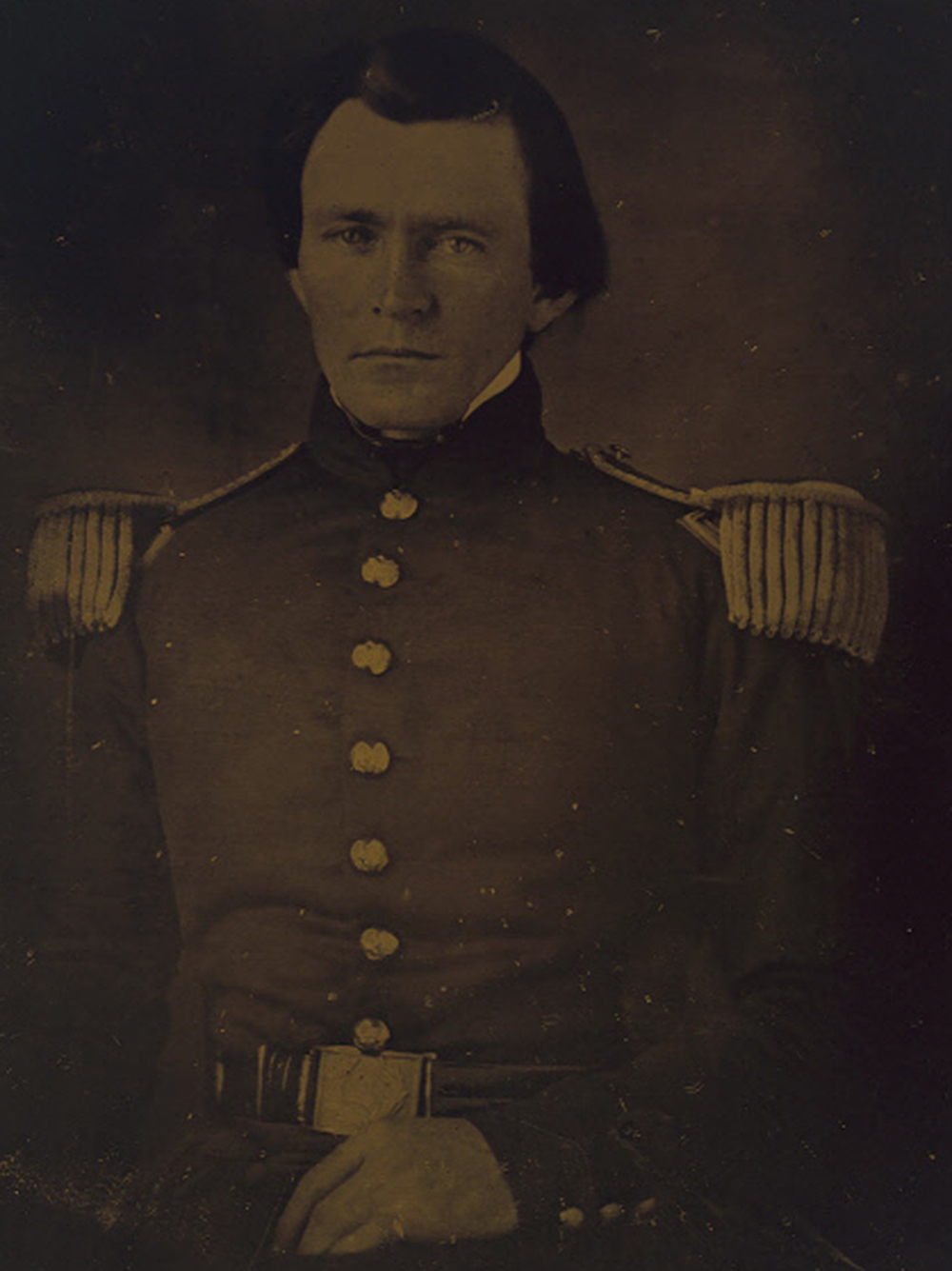

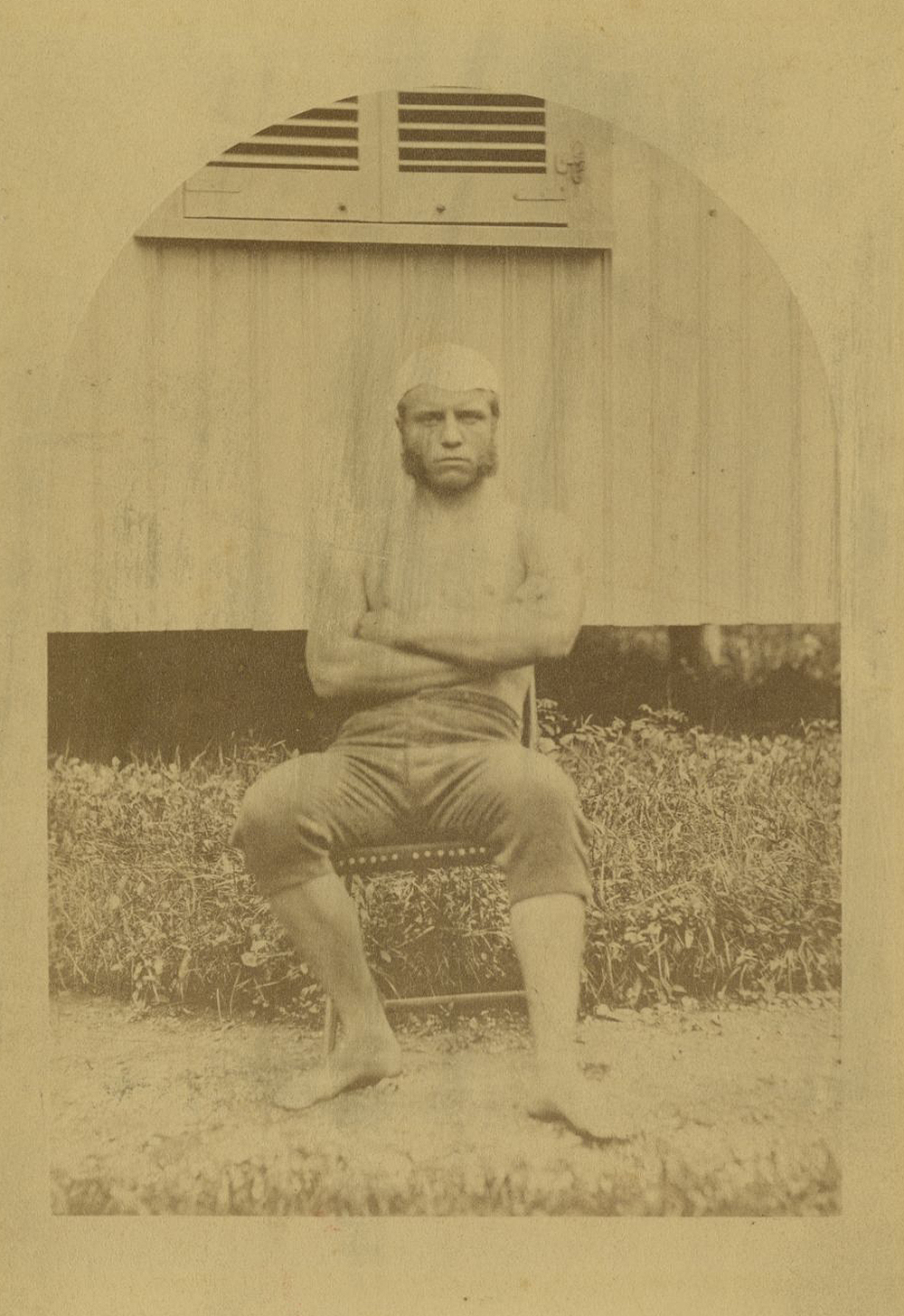

The great proliferation of online historical sexpot appreciation began in earnest in the early 2010s, at the height of the Tumblr era. Search “hot historical figures” on Tumblr and you’ll find your way to collections such as Historical Hotties (Toffaleti’s blog), Historically Handsome Men, Hot Historical Figures, Historical Hotties (another one), Historical Hotties (same title, different blog), Historical Hotties (again), History Hotties, Hot and Historical, My Daguerreotype Boyfriend, and Historical Hotties (a separate iteration from the other four). A few were dedicated to a mix of dead famous men and dead famous women; others also featured anonymous attractive people spotted in old photographs whose names have presumably been lost to history. Yet most were dedicated to appreciating the sex appeal of famous leaders, writers, composers, and public intellectuals of yore. Popular choices of this era include Ernest Hemingway, Robert Frost, Ulysses S. Grant, Lewis Thornton Powell (who attempted to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward in 1865), Hermann Rorschach (inventor of the Rorschach test and a dead ringer for Brad Pitt)—and, of course, Hamilton. Some, like Fuck Yeah History Crushes and Historical Eye Candy, remain active and are still updated frequently.

Dead-guy ogling, however, was not to be confined to a few blogging platforms. Variants on the theme have since blossomed all over: The Encyclopedia Britannica came out with a list of “11 Handsome Historical Figures”; the Washington Post ogled a hunky Michelangelo statue on display in Washington; in 2012 Bloomberg Businessweek published a story titled “Alexander Hamilton, Federalist Hunk” on the bemusing resurgence in the Founding Father’s popularity. (The story mentioned offhandedly that one Lin-Manuel Miranda, creator of the acclaimed In the Heights, was adapting the story of Hamilton’s life into “a concept album.”) Occasionally, mutations of the hot-historical-figures genre emerge, like blogs and listicles dedicated to living political figures in their younger years, hot world leaders currently in office, and problematically hot political figures (see Jezebel’s 2007 humor hit “So Is Ahmadinejad Kind of Hot?”). By the mid-2010s, BuzzFeed was running posts with the headlines “The 17 Hottest Dudes from History” (subtitle: “Dead Babes We’d Bang”), “A Ranking of the Hottest U.S. Presidents,” “The Definitive Ranking of Men on U.S. Currency by Hotness,” “Ranking All the U.S. Presidents by Their Hairstyles,” and “A Definitive Ranking of the 33 Hottest Men in Historical Paintings.”

The occasional one-off historical stone fox has, of course, been known to travel across social media as a lone entity, too. Like the photograph of a well-coiffed young Joseph Stalin that has known a few moments of virality (“That hair, though,” one admirer commented on Imgur; “Stalin was ballin’,” wrote another). Or the well-circulated 2016 Facebook “event” in which a user shared a photograph of young Ernest Hemingway and demanded to know, “Was Hemingway hot?”

?????? was he ?????? you will be banned if you try to talk about hemingway’s work. we are here to discuss his appearance ONLY. things he made with his brain do not matter one little rat’s ass.

Peter McGraw is a man who quite frequently gets asked to explain why certain things are funny. He is the coauthor of The Humor Code: A Global Search for What Makes Things Funny, which presents a “Benign Violation Theory” of why things are funny (and not): humor is what happens when something violates the expected or established way things ought to be, but not in a way that makes someone feel sad, threatened, or disturbed. The theory has its critics.

When I showed McGraw the Hemingway meme, he immediately recognized “benign violation” at work. For starters, he says, it gently defies an unspoken rule against speaking waggishly of the dead. Plus, in the world as we’ve heretofore understood it, “we’re supposed to be celebrating Alexander Hamilton’s contributions to U.S. history, Ernest Hemingway’s contributions to literature,” McGraw says. “Their brains, not their brawn. It diminishes them in some way.”

Wherein, of course, lies the “violation” part of the comedy equation. When it’s men being objectified, the norms have been violated. “Diminishing” as it may be to comment on someone’s sex appeal rather than their accomplishments, McGraw says, “this is clearly not out of bounds when you look at the reverse”: men talking about how hot women were or are.

Toffaleti believes that subversion is a significant part of the appeal of blogs like Historical Hotties. “Maybe objectifying male historical figures is a way for women to get a little revenge for all the times we’ve been objectified, and for all the women who have been written out of history,” she says.

The inversion of objectification’s traditional power structure isn’t lost on Kate Dobson, either. As she learned from a past job editing comic strips, comedy has to offer a reversal of expectations for it to be funny. It’s why she says she’ll never write a follow-up ranking of the hottest First Ladies, despite some popular demand for one: First Ladies’ attractiveness has been discussed enough already.

And crucially, McGraw says, what makes the “hot dead guy” concept such an evergreen amusement is that it’s ultimately complimentary—ensuring that it violates a norm, but not in a way that smacks of cruelty. It’s certainly more likely to be funny than talking about all these ugly intellectuals, he tells me with a laugh, “and what toads they were.”

The “ideal look” for a woman has long been known to go in and out of style—often, unfairly, in keeping with what’s least attainable at the time. Plumpness comes into vogue in times of scarcity, fair skin in eras of economic dependence on agricultural labor. Which may help explain why there’s no corollary phenomenon in which the women of, say, the Encyclopedia Britannica might arouse a similar fascination—the notion of a “beautiful woman” seems to fluctuate so wildly that a great beauty of one generation might well be considered plain by the next. But what is it about nineteenth- and early twentieth-century male beauty standards that have us so hot and bothered now?

The beards, for one thing. In Victorian England, around the mid-nineteenth century, anxieties about shaving led to a boom in facial hair. Conscientious men of the time, for reasons relating to health and godliness, were advised to let the hair on their faces grow unchecked. As a result, leaders and intellectuals throughout the Western world wore beards, which were then immortalized in portraits and artistic homages. Clean-shaven faces eventually came back in style, relegating the long, wild beard to communities of the very religious and the very lazy for several decades. But in the late 2000s and early 2010s, the beard returned to the mainstream—right around the same time the horde of Historical Hotties blogs began their ogling of the celebrities of the 1850s in earnest. (It remains to be seen, of course, whether that portends the return of the Henry David Thoreau neckbeard as a fashion statement.)

On a different, perhaps deeper level, the appeal of objectifying history’s great men may be rooted in the catharsis of irreverence. As film scholar Marcia Landy wrote in a 2011 essay on the role of historical comedy in film:

comedy has functioned as counter-history to undermine official narratives of the past…Once upon a time, professional historians denigrated films that purported to dramatize history, regarding them at best as mere entertainment or at worst as escapism, distortions, inaccuracies, and harmful fictions. Today, popular film and television through the lens of parody, farce, and satire are instrumental in offering a view of the past that runs counter to official historicizing.

Even outside the realm of cinema, you could argue that comedy rooted in the imagined sex lives and personal lives of historical figures could present a different, more human side of their stories than official biographies might. “As you grow up, you realize that these people we have federal holidays for were actually deeply flawed human beings,” Toffaleti says. “Sometimes you just want to knock them off their pedestals.” The assessment of attractiveness, of course, is usually (and rightly) divorced from the assessment of character. Still, the infusion of something so base as sex appeal into famous, well-trod narratives about men’s intellectual or moral greatness serves both to amuse and sometimes endear.

When Dobson set out to write funny dating profiles of each U.S. president for Hottest Heads of State, Volume One: The American Presidents with her husband, she found her own set of compelling counterhistories when she began combing through the library of First Ladies’ biographies. Books about the presidents themselves tend to go light on the personal stuff, and certainly the romantic stuff, she says (though certain exceptions exist). But in biographies of the First Ladies, there were often intimate details about the presidents’ romantic escapades, as well as their home and family lives. “So many of them were great presidents but terrible boyfriends; others were bad presidents, but they were amazing husbands,” she says. “I loved thinking about that instead of just thinking, What kind of President was he? Because it’s such a different quality set.”

That the flowering of the internet’s obsession with foxy historical figures, Hamilton in particular, can be traced to the middle 2000s is probably no accident. Ron Chernow’s acclaimed biography of Hamilton took hold of the best-seller list for three months when it was released in 2005; it was loved by history scholars and casual beach and vacation readers alike.

Hamiltonophilia had simmered at a low but palpable level for centuries before Chernow’s biography surfaced. One 1910 Atlanta Constitution article declared him the “Most Romantic Figure of the Early Days of the Republic” (in the “Romantic hero” sense, not “romantic comedy”), and at least some portion of the public fascination with Hamilton can be chalked up to the regal looks of his most famous artistic likeness: Giuseppe Ceracchi’s 1794 marble bust. According to a curator at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas, where it is now displayed, in this rendering “Hamilton appears in the guise of a Roman statesman with a classical profile and strong nose. A slight smile plays about his lips, while his furrowed brow suggests his powerful mind at work.” (Or as a freshman U.S. history classmate of mine put it after glimpsing a portrait based on that bust, Hamilton looks “FFILF-y.”) But as every Broadway fan and all their weary friends know by now, the biography inspired the musical that likely forever altered how history will remember Hamilton. He retains his spot on the $10 bill today largely because of his resurgent popularity.

In 2016, at the height of Hamilton mania, a popular Quora thread dissected the question, “Would Alexander Hamilton be considered ‘hot’ by today’s standards?” One user suggested a resemblance to Bryan Cranston; another argued that portraits probably had accentuated his better features. Perhaps most tellingly, the post also raised a second, separate question. After idly taking a good long look at the five-dollar bill, a poster wondered: “Was Abe HOTT?”