Dorothy Parker. The New York Public Library, Billy Rose Theatre Collection.

Marie Bashkirtseff (1858–1884)

Bashkirtseff was a Russian-born painter and sculptor who kept a diary from age thirteen until shortly before her death of tuberculosis at twenty-five. During that time she studied painting in Paris (at a private academy; the famous École des Beaux-Arts did not admit women until 1897) and began to establish herself as a gifted young artist. “I hate moderation in anything,” she wrote in 1876, the year she began to study art seriously. “I want either a life of continual excitement or one of absolute repose.” In fact, she chose continual work, for years following more or less the same schedule: up at six am, drawing or painting from eight am to noon and from one to five pm, with an hour-long meal break in between. Then she bathed and changed clothes, had dinner, read until eleven pm, and went to bed. (Sometimes she would draw by lamplight in the early evening before dinner, extending her workday by an hour or so.) Occasionally, she grew fatigued of the relentless schedule, but, as she wrote in 1880, “when I spend the day without working I suffer the most frightful remorse.” Learning that she had tuberculosis and would likely die young only increased Bashkirtseff’s determination. “Everything seems petty and uninteresting, everything except my work,” she wrote in May 1883. “Life, taken thus, may be beautiful.”

Marie de Vichy-Chamrond, Marquise du Deffand (1697–1780)

Madame du Deffand was an intimate friend and correspondent of Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Horace Walpole, and the hostess of a Parisian salon that stood at the center of the city’s intellectual life for forty years. In his book Written Lives, Javier Marías summarizes Deffand’s daily routine:

Her life followed a slightly disorderly timetable: she would get up at about five o’clock in the afternoon and, at six, receive her supper guests, of whom there might be six or seven or even twenty or thirty depending on the day; supper and talk went on until two in the morning, but since she could not bear to go to bed, she was quite capable of staying up until seven playing at dice with [the British politician] Charles Fox, even though she did not enjoy the game and was, at the time, seventy-three years of age. If no one else could keep her company, she would wake the coachman and have him take her for a ride along the empty boulevards. Her aversion to going to bed was due in large part to the terrible insomnia from which she had always suffered: sometimes, she would await the early morning arrival of someone who could read to her, and then, after listening to a few passages from a book, she could at last fall asleep.

The central event of Deffand’s day was supper—“one of man’s four aims,” she wrote; “I have forgotten what the other three are”—and she continued hosting her evening supper parties right up until her death at age eighty-three. “Exert all your talents,” she often told her cook, “as I more than ever require the aid of society to beguile the time.” As Marías noted, she was especially loath to be left alone at night. After her visitors finally went home and her servants retired, Deffand wrote, “I am left to myself, and I cannot be in worse hands.

Dorothy Parker (1893–1967)

“If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style,” Parker once said. “The first greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy.” Parker was only half-joking, or maybe not even half. Despite becoming a much sought-after writer, with high-profile, well-paying gigs at Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, Parker loathed the writing process and barely managed to get her articles in on time. She never followed any particular writing routine, although when she was a reviewer for The New Yorker there was a kind of weekly routine, a push-and-pull act between the reluctant author and her editor, which Marion Meade describes in her biography of Parker:

Almost from the outset, she set a precedent of being late with her copy, which was due at The New Yorker on Fridays. On Sunday mornings, someone from the magazine would telephone. Dorothy, reassuring, said that the column was finished except for the last paragraph and promised to have it for them within the hour. Throughout the day, the same routine would be repeated several times. Occasionally, she would claim she had just ripped up the column because it was awful. At that point, she would start writing.

She did this with all her editors. An editor at the Saturday Evening Post remembered the process this way: “You sit around and wait for her to finish what she has begun. That is, if she has begun. The probability is that she hasn’t begun.” An editor at Esquire confirmed that Parker “had a miserable time writing,” and compared the process of extracting copy to a difficult childbirth, with the editor as obstetrician—the operation was, he said, a “high-forceps delivery.” Parker hated it as much as her editors did, but she couldn’t change. She was once asked by an interviewer what she did for fun. “Everything that isn’t writing is fun,” she replied.

Marian Anderson (1897–1993)

Anderson was an American contralto who, in 1955, became the first black soloist to appear at the Metropolitan Opera, in New York. The conductor Arturo Toscanini said she had “a voice such as one hears once in a hundred years.” In her autobiography, Anderson wrote about her method of learning a new song, a more complex and delicate process than audiences might imagine. “I like to hear the melody first, to get something from the music before I have begun serious work on the words,” she wrote.

Then I read the [words] apart from the music; I want to know what it is about. I want to know something about the way in which the song was written. I try to saturate myself in everything that relates to it. When I put words and music together I try to reach deeply into the mood. If I concentrate, and if there is nothing in the song to create unexpected difficulties, the task is not hard. It is not always easy, however, to concentrate; your mind has to be free of distractions. Household and family obligations have their rights, and do occupy my thoughts a great deal, and other calls on my time may intrude. No matter how study has gone during the day, I take the songs to bed with me. Just before one is ready to sleep there comes the time of complete relaxation, and one lives the mood of the music. Suddenly one is wide awake, completely lost in the spirit of the song, and in a few hours, while all is still around one, a great deal is accomplished.

“Music is an elusive thing,” Anderson continued. Some weeks she worked on a song every day without making any progress. “Then,” she wrote, “suddenly there is a flash of understanding. What has appeared useless labor for days becomes fruitful at an unpredictable moment.”

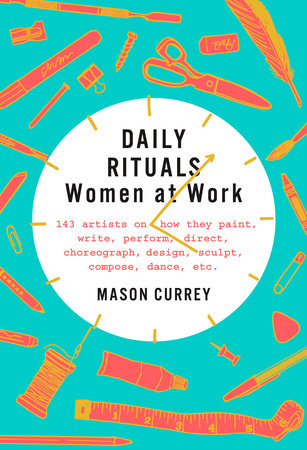

Excerpted from Daily Rituals: Women at Work by Mason Currey. Copyright © 2019 by Mason Currey. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.