View of Benjamin Reber’s Farm (detail), by Charles C. Hofmann, 1872. National Gallery of Art, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Rosellen Brown, author of The Lake on Fire, now available from Sarabande Books.

I try to keep it a secret but, though I’ve published six novels and many short stories, I’m a terrible storyteller. One of my friends even gave me a little pin to wear: it was in the shape of a gravestone, with an inscription that read my plot.

I take heart from a sentence by Borges, the opening of his Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius: “I owe the discovery of Uqbar to the conjunction of a mirror and an encyclopedia.” Stories can be conjured from many sources—some directly, some obscurely—but given independent life by their unlikely juxtaposition. This borrowing is not thievery, but the alchemy we call fiction. I can credit three sources for my most recent novel, The Lake on Fire. One was a few pages of journalism, one a sentence from a novel, and the last a memoir. For some of us, this is how the stew (not the sausage) is made.

More years ago than I like to acknowledge, I came upon a fascinating book about the immigration of America’s often unwelcome, unglamorous Eastern European Jews. It was called Poor Cousins, written by Ande Manners and published in 1972. I learned to my great surprise that in the 1880s there was an optimistic circle of European Jewish philanthropists who thought that tilling the soil would ennoble the poor of Russia’s cities. They didn’t worry that the czar’s prohibition against Jews’ owning (thus having experience with) land might be a disability; rather, they considered their idea a liberation from such strictures. A group called Bilu decamped to Palestine, but around twenty-seven cadres of young people from Odessa, Kiev, and lesser places who called themselves “Am Olam,” or People of the Earth or the Eternal People, went to the United States with token financing and disastrously under-researched direction by the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society. They arrived with no English, a naive belief that they had broken free of anti-Semitism, and no understanding of the difficulties even experienced farmers underwent as they broke the plains. Remember the books we read in high school? Giants in the Earth, My Àntonia, even the Little House novels—oh, those grasshoppers, those blizzards, those drought- or rain-destroyed crops, those Indian attacks, those randomly ravaged harvests!

Should it have been a surprise that each little community flamed out, each in its own way, depending on locale and luck? The farm in Sicily Island, Louisiana, fell to the yearly flooding of the Mississippi and the onslaught of yellow fever and malaria. According to Manners, one

scholar and leader…wrote bitterly: “They called it a Paradise, but we found nothing thereunto pertaining save some poisonous serpents, much however of Hell. A viler spot on God’s Earth it would be hard to find and there our unfortunate, much tried co-religionists were to learn a love for agriculture.”

New Odessa in Oregon could not sustain the preference its supposed farmers had for philosophical debate and free love over the dreary task of walking behind a plow. Most simply went under less dramatically for lack of expertise and economic feasibility. None of the communities survived long; only Woodbine in Cape May, New Jersey, hung on long enough that its pioneers could take factory jobs in New York City and farm on the side.

So the philanthropists’ experiment ignominiously succumbed, but from my narcissistic perspective its brief existence gave me something to seize and use: the beginning of a story. I moved to Chicago just as I finished searching for a way to animate this bad-luck scenario. There I discovered (before the useful public relations assistance of Erik Larson) the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. What if I situated such an idealistically founded farm in Wisconsin, cribbed the very town from which Theodore Dreiser sent forth his Sister Carrie—the fictitiously but pointedly named Columbia City—and imagined a Jewish immigrant of the same age as Carrie, about whom Dreiser wrote (in what I consider the only felicitous line in his riveting but clumsily written book):

When a girl leaves her home at eighteen, she does one of two things. Either she falls into saving hands and becomes better, or she rapidly assumes the cosmopolitan standard of virtue and becomes worse.

Thinking of Carrie, I created my characters, Chaya-Libbe Shaderowsky and her little brother Asher, who become immigrants twice over by getting on that train in Columbia City and escaping the debacle of their farm to discover the thrills and brutal realities of Chicago. Before my novel comes to an end my two innocents have confronted the Gilded Age and all its contradictions, its devotion to beauty and grandeur best represented by the glorious fair, alongside its indifference to unspeakable poverty worsened by a worldwide depression and the bureaucratic neglect of the very disposable men and horses dying in the streets.

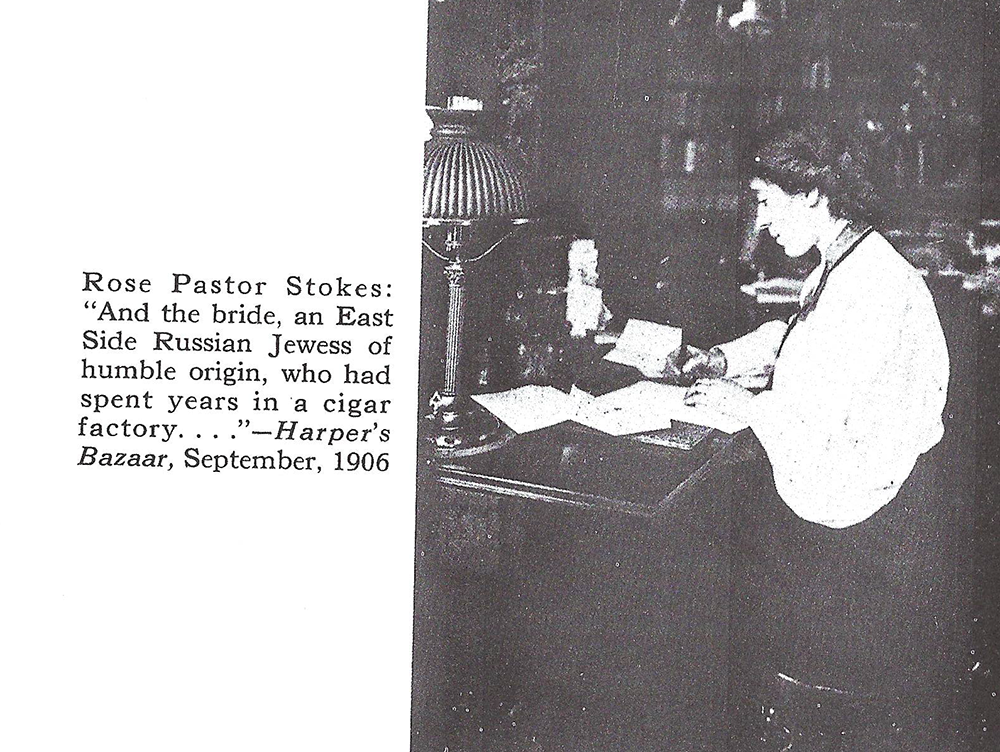

There Chaya is courted by a young man suspiciously similar to a (genuine) wealthy Episcopalian railroad heir, a New Yorker named Graham Stokes—my suitor is named Gregory Stillman—who does his best to eschew the cosmopolitan standard of virtue mocked by Dreiser and call himself a socialist. The woman he loves in real, not fictional, life was named Rose Pastor Stokes and her book, the third that influenced mine, is I Belong to the Working Class, a fiercely didactic memoir she left unfinished at her death in 1933. Rose Pastor was a Russian-born journalist who wrote poetry and one play called The Woman Who Wouldn’t. She, like my Chaya, worked in a cigar factory until, in a wedding celebrated as a Cinderella affair, she married Stokes, his money, his name in wealthy circles, and his apparent (though ultimately inadequate) commitment to her ideals. Later she helped found the American Communist Party, championed birth control, and took on “the Negro question.” Like Jane Addams (who also appears in my book), she opposed World War I and generally, with great vigor and courage—and to much opprobrium—managed to live a life entirely opposite that of Dreiser’s young woman, who, falling, drags quite a few others along with her.

Possibly a novelist should not admit to having plundered so many sources to make a single book. But all of us are influenced, casually or profoundly and often without our even realizing it, by the lives and work of others. In the end, I dare to think, what matters is not the provenance of the variously colored threads but the ingenuity and passion with which they are woven.

The Three Books

Manners, Ande. Poor Cousins. Coward, McCann, & Geoghegan, 1972.

Dreiser, Theodore. Sister Carrie. (Many, uncountable editions), 1900.

Shapiro, Herbert, and David L. Sterling, eds. I Belong to the Working Class: The Unfinished Autobiography of Rose Pastor Stokes. University of Georgia Press, 1992.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Leland de la Durantaye, author of Hannah Versus the Tree

• Patricia Miller, author of Bringing Down the Colonel

• Helen Klein Ross, author of The Latecomers

• Monica Muñoz Martinez, author of The Injustice Never Leaves You

• Tatjana Soli, author of The Removes

• John Wray, author of Godsend

• Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine

• Ken Krimstein, author of The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

• Katherine Benton-Cohen, historical adviser for the film Bisbee ’17

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing