Wire frame, American flag, c. 1880. Smithsonian Gardens, Horticultural Artifacts Collection.

Few lines in American history are as well-known as those comprising the first verse of Francis Scott Key’s “Star-Spangled Banner.” Written on a ship floating in Baltimore Harbor after American forces survived a bombardment from British ships during the War of 1812, the opening stanza can still be heard emanating from the sites of political rallies, military exercises, and athletic contests across the United States.

Key’s colorful description of the national flag flying high above Fort McHenry is a triumphant expression of American patriotism. It holds a special place in the minds of the nation’s citizens, even if many of them are unable to recite its lyrics accurately. While the most famous line of the National Anthem is the opening exclamation, “O! say can you see by the dawn’s early light,” the most infamous line appears in the third of the song’s four original sections. Assailing the enslaved people who had absconded from their American owners and volunteered for the British armed forces during the war, it surmises these traitorous bondmen had either fled in fear before the Battle of Baltimore or lost their lives in the process of betraying the pro-slavery republic: “No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave.”

After reveling in the alleged demise of these formerly captive people, the song repeats its inspiring crescendo, “the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave / O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

Key’s lyrics did not go unchallenged. Years later, the Quaker abolitionist Dr. Edwin Atlee parodied the “National Song” to illuminate the plight of the fugitive slaves who fought alongside the British against the United States in the hope of becoming free. Unlike Key’s original poem, this revision depicts the plight of all enslaved people whose blood daily streamed under the lash of their American oppressors, while the national banner, “With its stars, mocking freedom, is fitfully gleaming.”

Instead of a land of liberty, the United States was a shelter for slavery: “No refuge is found on our unhallowed ground / For the wretched in Slavery’s manacles bound.” Should the nation fail to achieve its boasted ideals, “our star-spangled banner at half mast shall wave / O’er the death-bed of Freedom—the home of the slave.”

As the two contrasting compositions demonstrate, the American flag was from its inception a controversial and contested symbol. For slavery’s defenders, the flag represented countless liberties, including the right of white citizens to buy, sell, and own Black people. For slavery’s opponents, it symbolized the American republic’s failed promise of freedom. In a nation shamed by slavery, its flag was a blot that invited and deserved condemnation both at home and abroad.

In the summer of 1822, while traveling through Paris, Kentucky, James Dickey’s heart leapt when he heard music in the distance, which he interpreted as the approach of a military pageant or parade. The minister’s anticipation quickly turned to terror when instead of witnessing a patriotic procession, he saw dozens of enslaved people walking together in pairs, dragging a forty-foot-long chain between them. Even more revolting to him than the sight of as many as seventy captive people being led through the woods like animals was the fact that one of them carried a flag bearing the distinctive stars and stripes of the American standard.

“My soul was sick,” Dickey wrote of the disturbing scene. “As a man, I sympathized with suffering humanity, as a Christian, I mourned over the transgressions of God’s holy law, and as a republican I felt indignant, to see the flag of my beloved country thus insulted.”

A flag-carrying coffle could have been spotted at almost any time and place in the antebellum South and few, if anyone, outside the local area would have noticed; in this case, however, the story spread nationwide because of the efforts of the offended eyewitness. No ordinary observer, James Dickey was one of the United States’ earliest and most influential abolitionists west of the Appalachian Mountains. Born in Virginia and raised in South Carolina and Kentucky, he identified with Southern people and traditions. But the “abominations of slavery” caused him to forsake the land of his “childhood and youth” and move to the opposite side of the Ohio River.

After witnessing the coffle, Dickey fired off an angry letter to the local Paris Western Citizen. While proud of “Columbia’s free born sons” for turning the Kentucky wilderness into a commercial emporium, he decried the traffic in human beings, “a business commenced at first on a moderate scale, in Kentucky, but now grown so enormously as to be become truly alarming.” He also denounced the use of the American flag as a symbol of the nefarious trade. It was hard to imagine a greater insult to the republic and its founders than “to hoist the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ the flag of freedom, the Eagle of proud America, over a set of poor unhappy slaves, fettered to misery, to despair, who never knew Liberty, save in dreams of the night, or the airy visions of the day.” It was, Dickey concluded, a “shameful prostitution.” Others agreed.

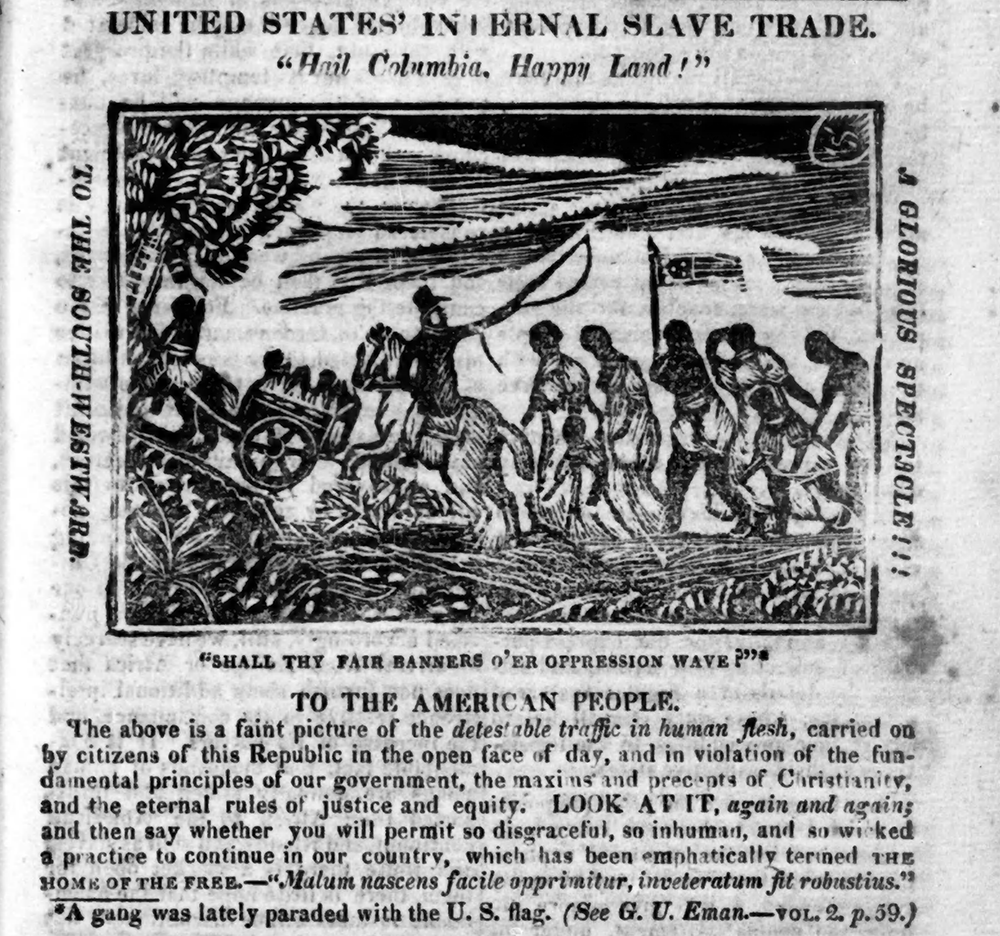

In the Genius of Universal Emancipation, the United States’ first significant antislavery newspaper, editor Benjamin Lundy addressed the incident as soon as he became aware of it. Besides reprinting Dickey’s letter and calling the Kentucky slave coffle “a shame and foul dishonor to the flag of my country,” he published a front-page visual aid to fully convey his revulsion. The crude woodcut centers on a well-dressed white man on horseback, who while holding a whip in his outstretched arm menacingly, leads a coffle of bowing Black bondpeople across a field.

In front of the slave driver, a horse-drawn cart full of enslaved children moves forward, while behind it follow seven captive men, women, and children on foot and in various states of dress and undress. Nearly all the distinguishing characteristics of the ambulatory figures are lost in the amateurish engraving—yet the star-spangled banner that is held aloft by one of the captives and flies above them is impossible to miss.

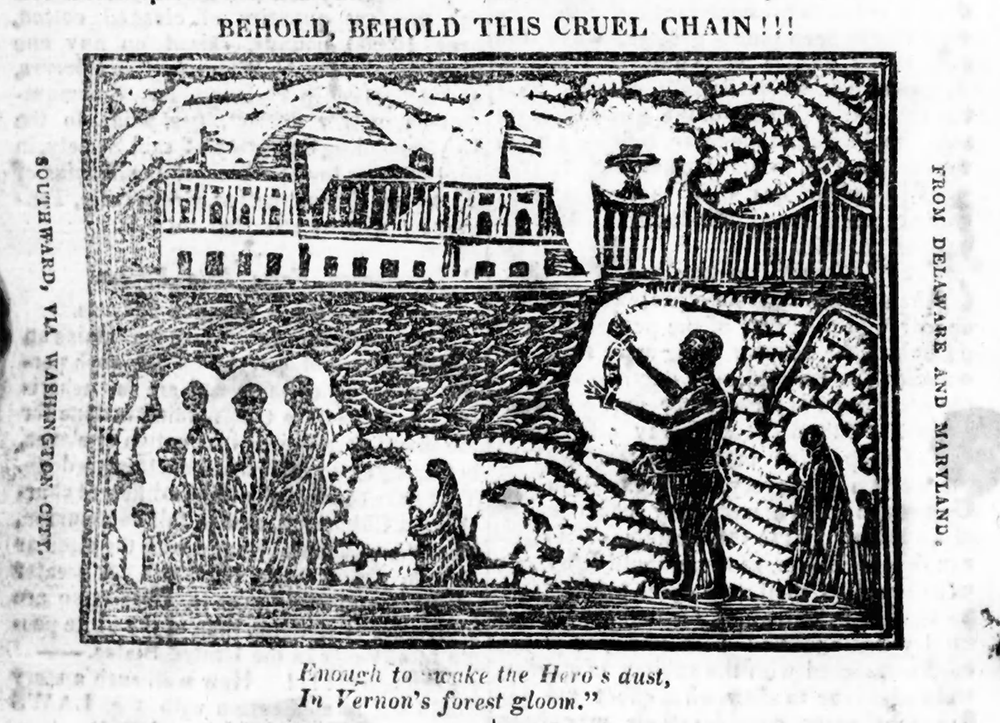

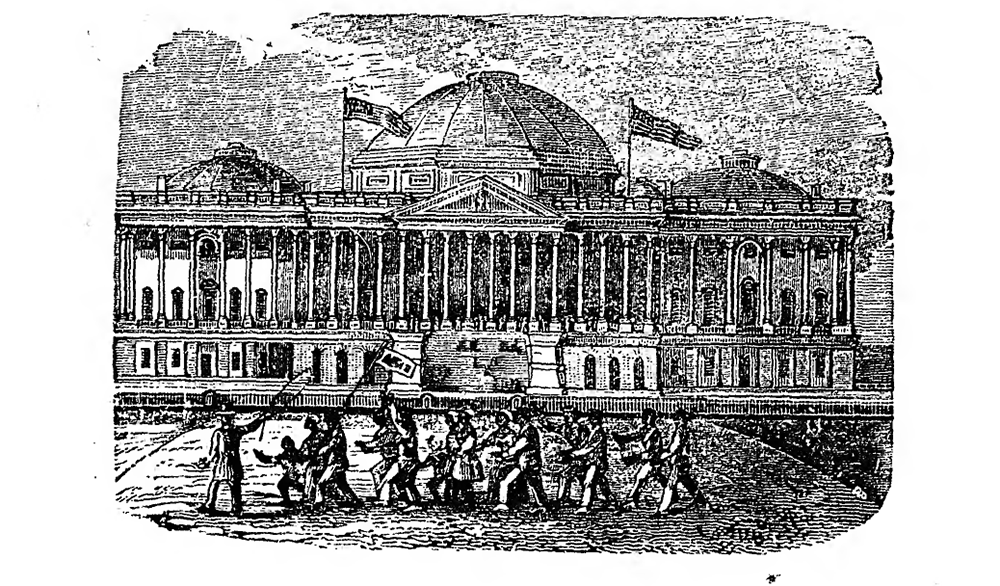

When abolitionists witnessed the Washington slave trade in person, the experience was often epiphanic. Vermont’s William Slade was moderate on the issue of antislavery when first elected to the House of Representatives in 1831. Several years of residency in the nation’s capital, however, convinced him to join a group of northern politicians who made the abolition of slavery and the slave trade in the District a legislative priority. In a speech before the Congress in 1835, he entreated “that measures may be taken to put an end to slavery here, and especially that here, where the flag of freedom floats over the Capitol of this great Republic, and where the authority of that Republic is supreme, the trade in human flesh may be abolished.” The “Character of the country” was at stake, Slade insisted, leading him to decry the turning of men into merchandise “within sight of the Capitol in which their Representatives are assembled, and on whose summit wave the stripes and stars of freedom?” Fortunately, there were those across the nation who “as Americans” were reaching out “their hands to wipe out the stain from the escutcheon of their country.”

When Congress ignored Slade’s advice, he persisted. In January 1839, the sight of a slave coffle near the Capitol sent him to the office of Joshua Giddings, the freshman representative from Ohio and noted abolitionist. To “arouse Mr. Giddings’s indignation and inspire him with renewed courage and zeal in the fight upon which he had entered,” Slade detailed the scene: “This day a coffle of about sixty slaves, male and female, passed through the streets of Washington, chained together, on their way South.” The captives trudged alongside a wagon that carried women and children who because of injury, sickness, or age, were unable to walk. Guiding the coffle was a “being in the shape of a man” who continually chastised the group with a large lash. “This was done in the daytime, in public view of all who happened to be so situated as to see the barbarous spectacle.”

Slade was furious. Several days later, despite the notorious “gag rule,” which since 1836 barred the introduction of any antislavery petitions in the House of Representatives, he convinced the chamber’s clerk to read the opening portion of a series of resolutions, demanding information on the men responsible for the coffle. Representatives stopped the clerk before he could finish and tabled the resolutions indefinitely.

Undeterred, Slade alerted antislavery writers and editors, who immediately commented on the incident. A correspondent for the Boston Courier undoubtedly spoke for many of the paper’s readers when he protested, “Here, at mid-day, under the eaves of the capitol of the oldest republic in the world, the capitol of a country boasting to be the advocate of liberty and human rights, over whose walls the star-spangled banner was then floating in majesty, a band of men, chained together, were driven by, in the presence of the American people! Shame! shame!”

While Slade continued to work toward the relatively conservative goal of eliminating slavery and the slave trade in Washington, Giddings became the most radical abolitionist congressman in history. To convince the unconverted of the righteousness of his cause, he regularly cited the trafficking of enslaved people in the nation’s capital. Giddings reserved some of his greatest scorn for the slave owners and dealers who plied their trade under the national standard. In a speech before the Congress, he blasted his colleagues for allowing city residents to traffic in the “the bodies of men, women, and children.” Addressing the Speaker of the House of Representatives directly, Giddings railed, “Here, sir, in view of this hall, under the shadow of the ‘star spangled banner’ which floats over this edifice, consecrated to freedom, to the maintenance of the undying truth that ‘governments are instituted to secure all men in the enjoyment of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,’ these hucksters in human flesh critically examined the bodies and limbs” of these mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters, whom they considered only as property. “I doubt whether any slave market in Africa was ever attended by more expert dealers in human chattels, than was the market of this city, which profanes the name of Washington.”

Though he did not mention it specifically in his speech, Giddings was well aware of the notorious slave pen operated by William H. Williams, who flew an American flag at the corner of 7th and B Streets, just a few blocks from the Capitol. For more than twenty years, the distinctive yellow structure was a local institution. “In an era before the memorials to Washington or Jefferson (much less the yet-unknown Lincoln) had been erected,” notes historian Jeff Forret, “DC travelers oriented themselves based on the Yellow House, which stood as a prominent landmark within the nation’s capital.” For slavery’s enemies, there was no greater symbol of the failure of American freedom.

In the Boston Emancipator, Henry Stanton and Joseph Lovejoy wondered how slave markets like Williams’ could exist in the capital city of a nation that proclaimed all men were created equal. In the federal district, “under the very shadow of the capitol,” the slave trader yoked, branded, chained, and scourged his “human cattle.” He advertised his “flesh” products in the local papers, hung his sign in open public, “as boldly as if he were a dealer in dry goods or groceries.” If that were not enough, he flew “the flag of his country over his den of despair” while letting “its stars and stripes steam in the breeze of heaven.”

After learning of William’s slave pen, American Anti-Slavery Society founder James Miller McKim traveled from Philadelphia to Washington to see the facility himself. Upon entering the “Slave-factory,” his heart sank. In front of him were “about 30 slaves of all ages, sizes, and colors,” crammed into a small room in the building’s basement, where they awaited being sold at auction. “The hypocrisy of this nation!” McKim exclaimed. “These are some of the abominations that exist in the District of Columbia! the national domain of the American REPUBLIC! within sight of the Capitol and under the stars and stripes of our national flag!”

Of course, the irony of a slave pen standing in the capital of a nation conceived in liberty was most evident to the people held captive inside the compound. Though evidence of what they thought is wanting, at least one extant record offers some insight. In 1841, while working in Washington as a musician, Solomon Northup, a free Black man from upstate New York, awoke in a jail cell inside the pen after being incapacitated by his employers the previous evening. Twelve hellish years later, after being transported to Louisiana and enslaved, he managed to secure his freedom. Upon returning to New York, Northup published his autobiography. In the wildly successful Twelve Years a Slave, he described his brief stay in the slave prison in graphic detail. “Strange as it may seem, within plain sight of this house, looking down from its commanding height upon it, was the Capitol,” he recalled. “The voices of patriotic representatives boasting of freedom and equality, and the rattling of the poor slave’s chains almost commingled. A slave pen within the very shadow of the Capitol!”

Excerpted from Symbols of Freedom: Slavery and Resistance Before the Civil War by Matthew J. Clavin, published by NYU Press. Copyright © 2023 by New York University. Reprinted by permission.