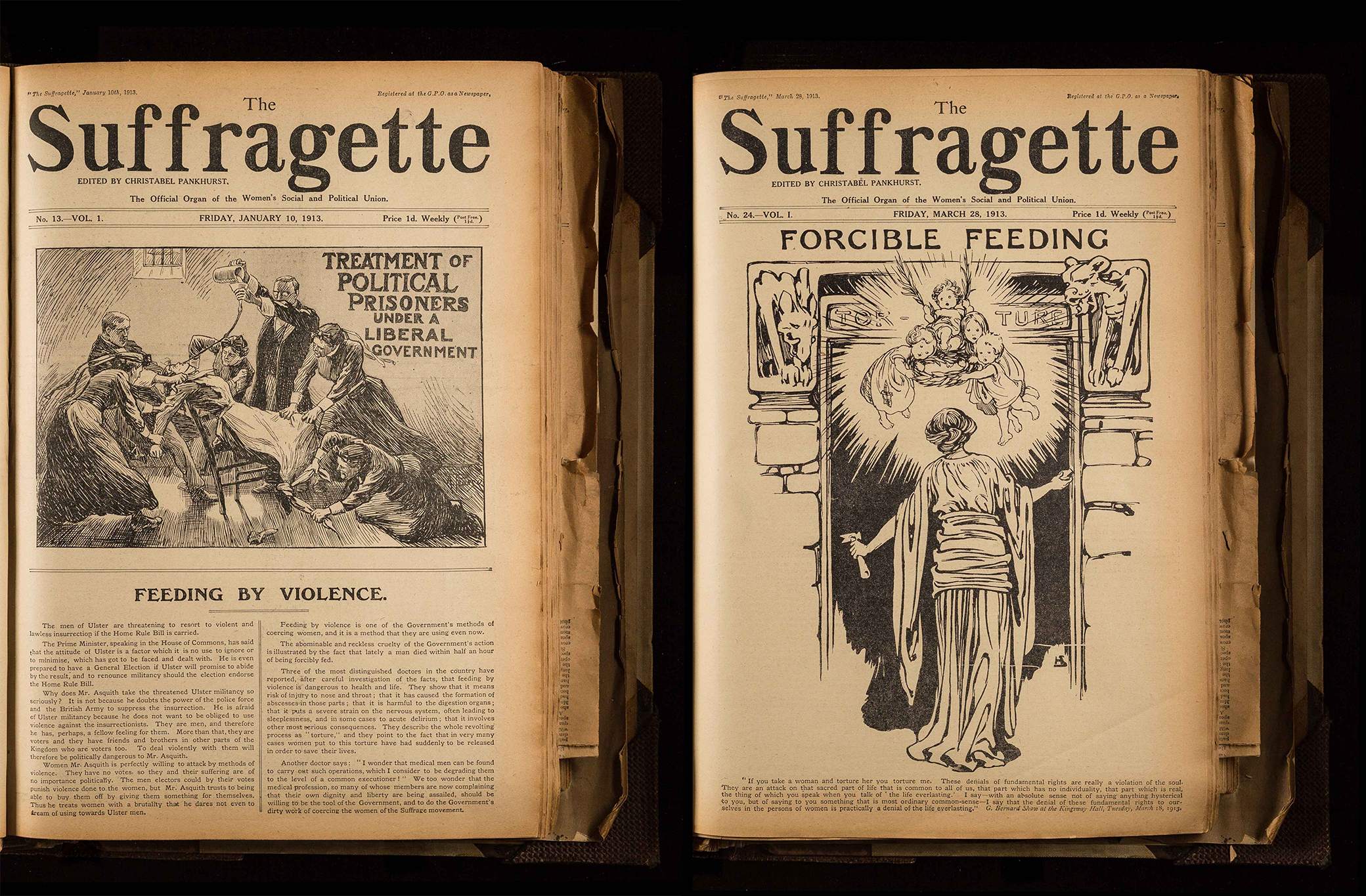

Covers of The Suffragette, 1913. London School of Economics Digital Library.

The East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS) was from its inception in 1912 a radical, militant, working-class, feminist organization. It was not solely concerned with votes for women, although suffrage was the primary focus of its activities. It was a community organization that admitted men, but it was always led by women. Its main purpose was to expose the exploitation and oppression of women in all aspects of life. “Our cue,” wrote Sylvia Pankhurst, one of the organization’s founders, “was to fan the flame of popular enthusiasm and to broaden our movement to take in even greater numbers and new sections.” Moreover, “it was necessary to rouse the poor women of London, the downtrodden mothers whose lot is one dull grind of hardship in order that they may go in their thousands to demonstrate before the seats of the Almighty.”

The ELFS used militant tactics and regarded itself as part of the labor movement, for it saw the achievement of equality and emancipation as inseparable from a socialist organization of society. Most important, Pankhurst interpreted socialism as working-class self-emancipation and applied this to the working-class women who joined: “We must get members to work for themselves and let them feel they are working for their own emancipation,” she said. Pankhurst also believed that building organizations of working women to fight for women’s rights was part of the working-class struggle for socialism. Writing to Captain White, a friend and supporter, in 1914, she explained:

I am a socialist and want to see the conditions under which our people live entirely revolutionized, but because I believe nothing will be accomplished without the help of women, I feel that my first work must be to do what I can to secure for women the entrance into the political scheme, without which they can never play anything but a subordinate part in the social reconstruction.

The immediate tactical objective of the federation, like that of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU)—ELFS was at first a branch of this larger organization—was to force the Liberal government to draft a bill enfranchising women and to maintain a rigorous campaign against the government until this was achieved. ELFS/WSPU members heckled Liberal politicians at meetings, held public debates, and organized demonstrations and mass marches. When imprisoned, they went on hunger strikes and were force-fed along with the rest of their suffragette sisters.

However, even though the ELFS was still formally a part of the WSPU, there were substantial tactical differences between the two. The federation would not attack the Labour Party, even Labour candidates not sympathetic to women’s suffrage or those who would consider woman’s suffrage only in the context of full adult suffrage. This policy was necessary to maintain support among political activists in the East End. Pankhurst made her position clear about working with men when she wrote a Mr. Lapworth, an East End friend:

It is so hard to induce working women to come out and make speeches and really take a prominent part in political movements that we must, even apart from the vote, be constantly laying emphasis on the woman’s side of things; but nothing is further from my wish than to be bitter and disagreeable towards the men and especially the men down here who have stood by us so splendidly.

Pankhurst and the American suffragist Zelie Emerson knew that militant tactics would be necessary to establish the ELFS and to create sufficient publicity to enlist more women into its ranks. On the evening of February 14, 1912, the ELFS held its first public meeting at Bromley Public Hall on Bow Road. Afterward those attending marched to the local bank and police station, where they broke some windows. Emerson and Pankhurst were arrested and imprisoned. Their fines were paid anonymously by Pankhurst’s mother, Emmeline, and they were quickly back in action.

Another demonstration was organized for February 17, and this time an undertaker’s parlor, the Public Hall in Bromley, and the local Liberal Club ended up with broken windows. Pankhurst, Emerson, Mrs. Watkins (a local dressmaker), and Annie and Willie Lansbury (the son and daughter of Labour leader George Lansbury) were among those arrested. The next day at the Thames Police Court, Willie Lansbury, Emerson, and Pankhurst were sentenced to two months’ hard labor; no fines were offered as options. The others were given one month’s service. The sentences illustrate the government’s response to suffragette activity, for they were unusually harsh for the crime of window breaking. The East End men and women sentenced to jail for the suffragette cause were making sacrifices far greater than those the suffragettes of the respectable West End had to make. Jobs were lost, and children, husbands, and other relatives had to be cared for by relations or friends or had to look after themselves. The treatment of working-class suffragettes in the prison was harsher than that meted out to the wealthy and influential.

The brutal treatment of the suffragettes by the Liberal government has been well documented. A woman who refused to eat would be held down by four to six male and female prison officials. A feeding tube would be inserted through her nose, and a gruel—often laced with brandy—would be fed into it. The prisoner usually struggled, screamed, fainted, and, after the ordeal, vomited. Suffragettes afterward spoke of the pain and the inner rage at the humiliation endured.

When Sylvia Pankhurst was imprisoned in February 1913, she immediately went on a hunger strike and this time decided to fight when the wardens tried to force-feed her. In an article for the Suffragette titled they tortured me, Pankhurst described how she hid in a corner of her cell, clutching her prison comb, brush, shoes, and basket. She intended to throw them at the warders when they entered, but at the moment they walked in, she couldn’t do it.

It took six warders and two doctors to hold her down and force the tube through her nasal passages. After the feeding was over, she vomited, then fainted. This torture went on twice a day for a month. In this period she lost thirty-five pounds, dropping from 132 to 97 pounds. The experience was so painful that she could hardly sleep. Pankhurst felt that her name and prominence in the suffrage movement resulted in her being treated with unusual viciousness. She was locked in solitary confinement and not allowed to exercise with the other prisoners.

In order to assure the suffragettes outside that she was resisting, she smuggled a letter, via Zelie Emerson, out of the prison to her mother:

Dearest Mother,

I am fighting, fighting, fighting, I have four, five and six wardresses every day as well as two doctors. I am fed by a stomach tube twice a day. They prise open my teeth with a steel gag pressing it in where there is a gap in my teeth. I resist all the time. My gums are always bleeding. The night before I vomited my last meal and was ill all night, and was sick after both meals yesterday. I am afraid they may be saying we don't resist. Yet my shoulders are bruised with struggling whilst they hold the tube into my throat. I used to feel I should go mad at first and be pretty near it, as I think they feared, but I have gotten over that.

Emmeline managed to get her daughter’s letter published in the Daily Mail, and a renewed outcry against forced feeding resulted. However, nothing was done to remedy the situation. Pankhurst and Emerson resumed their protest by beginning what the Suffragette called a “new and terrible form of protest,” the hunger and thirst strike.

They were brutally force-fed. Pankhurst began pacing up and down in her cell day and night—adding a sleep strike to the hunger and thirst strike. After she collapsed unconscious, the doctors ordered her release. She had been imprisoned for five weeks. Sylvia Pankhurst was subjected—or perhaps subjected herself—to more hunger strikes and forced feedings than most suffragettes.

Sylvia Pankhurst had an extraordinary ability to recruit to the ranks. Annie Barnes, a Stepney woman who joined the ELFS in its early years and later became a Stepney councillor, remained friends until Pankhurst left for Ethiopia in 1955. “Mind you,” Barnes later said, “Sylvia was such a wonderful woman she only had to say something, and you wanted to do it.” Barnes’ recollection of how she was recruited to militancy was not an untypical story.

At the first ELFS/WSPU meeting that Annie attended, Pankhurst gave a pep talk. “Well, you new recruits won’t be any good unless you are prepared to face anything, and I mean anything. You will be sometimes in danger.” Having led a somewhat quiet and sheltered life, Barnes didn’t know what to make of this speech. However, at the second meeting, Pankhurst asked for a volunteer. “This box in front of you is padded,” she explained. “I want someone to be put in the box and taken to the House of Commons to the tradesmen’s entrance. Everything has been arranged.” She then outlined the plan: “We want someone to be delivered as goods, so in the night she can get out and go up to the public gallery and hide. At ten o’clock tomorrow when the House opens you’re to go to the part of the gallery immediately above Asquith’s desk.”

Barnes could not volunteer for that assignment, because she knew she could not risk imprisonment. She was too afraid of her parents’ reaction. But another woman volunteered and threw a three-pound bag of flour over Asquith’s head! The next day the newspaper headlines said, asquith floured all over. Barnes did volunteer for other, equally risky assignments. Her very first mission was to go with Pankhurst and others to the top of London Bridge with carrier bags full of “Votes for Women” leaflets to throw down at people. It was not only dangerous but exhausting, for the women had to climb up and down the narrow spiral staircases before they were caught by the police.

“Be as quick as possible,” urged Pankhurst. “Throw them over and get down quickly because the police will be after you.” The women were stopped by the police, but managed to feign innocence and escape. “The East End had been so quiet, and all at once it was tense with excitement. Meetings here, meetings there. It was marvelous,” Barnes recollected.

The women members were very busy political activists. The federation had meetings twice a week, once in the afternoon and once in the evening. This way, both housewives and working women could attend. In the spring and summer months there were fortnightly Sunday open-air demonstrations. It was always difficult to get large crowds of women to join these demonstrations because “mothers could not come out on Sundays as the children have to be looked after, and she is too tired to come out after the weary preparation of dinner.” The federation set up nurseries so that more mothers could participate. Classes were set up to train women to become public speakers.

A member named Rose Leo took charge of these popular and successful classes. They were held at several different locations, and male speakers would be invited so that the women could practice heckling and learn how to deal with hecklers. In December 1913, the ELFS/WSPU organized a weeklong suffrage school. The lectures and discussions covered a wide range of social problems facing women as workers and as housewives. They included: the legal position of women, wages, housing, infant mortality, sex education, trade unionism, radical and socialist history, female psychology, and the effects of hunger striking and forced feeding. Lectures on such topics as sex education and female psychology were unusual at this time. They give an idea of the breadth of the ELFS/WSPU’s feminist radicalism as well as of the women’s issues that concerned it.

The schools and the meetings, the planning and organizing of demonstrations, marches, and rallies, all trained a number of East End women who remained politically active as leaders even after the suffragette activity ended. Annie Barnes wrote, “Being in the suffragettes did a lot for me. I couldn’t say ‘Boo’ to a goose before that. It really brought me out.”

From Sylvia Pankhurst: Sexual Politics and Political Activism by Barbara Winslow. Used with the permission of the publisher, Verso Books. Copyright © 2021 by Barbara Winslow.