Managers of the House of Representatives of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson, by Mathew B. Brady, 1868. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

On The World in Time podcast in May 2019, Lewis H. Lapham spoke with Brenda Wineapple about The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation. This transcript has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Lewis H. Lapham: Perhaps you can begin by setting the American scene in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Who is Andrew Johnson and what is the state of the Union in the spring and summer of 1865?

Brenda Wineapple: To set the stage, you just back up for a second and think about the Civil War, one of the bloodiest conflicts in the history of war—and certainly for the United States—where 750,000 people were killed, and the number keeps increasing. In that spring the war more or less came to an end with the signing of the peace agreement at Appomattox. But shockingly, Abraham Lincoln, recently inaugurated for a second term, was assassinated. What’s interesting to me is at that juncture a man named Andrew Johnson takes the oath of office and serves as president for three years. We know very little about him and what happened, which is to say, toward the end of his term as president, he was impeached. That to me is shocking because here we had a bloody conflict, some people called it a slaughter, where the country was divided North against South, South against North, in a country that had had the institution of slavery thriving since its inception. That institution was finally eradicated—or presumably eradicated. And you have the first ever presidential assassination. So it’s a crucial time in American history.

LHL: Johnson was Lincoln’s vice president. He’d been on the ticket in 1864, but he was a Southerner. He was from Tennessee. He was a Democrat and had been a slave owner.

BW: Yes, he was all of those things. And Lincoln chose him to be his vice president. Or, if he didn’t choose him outright, he certainly had no objections to him being chosen because Lincoln was afraid that he was going to lose the election. Things hadn’t been going well for the North, there was a groundswell of opposition against Lincoln, and he thought, as many think today, the best way to win would be to balance the ticket. He chose Andrew Johnson, who, as you say, is from Tennessee and was from a different party. But what made Johnson unique among Southerners was that he was the only United States senator to stand up in the Senate against secession and announce that he did not want the South to secede. Whatever else he was, he was an enormously strong unionist and became a military governor appointed by Lincoln in Tennessee.

At this time in 1864, Johnson had a terrific reputation and people in the North were proud that they had this outspoken Southerner on their side. Lincoln’s understandable, human, and fatal mistake was that he didn’t think he was going to be assassinated. Whatever he thought personally of Johnson, he believed he was going to serve out his term and that Johnson would be a forgettable vice president, as many are. But obviously it didn’t work out that way.

LHL: Because very soon after Johnson’s accession, which is in April of 1865, he begins to dictate policy that is opposed to Lincoln’s program of Reconstruction.

BW: To be fair, we don’t really know what Lincoln’s program of Reconstruction would have been. There are competing ideas about that. The generals Sherman and Grant remember it one way, secretary of war Edwin M. Stanton remembers it another way. We have some of the comments that Lincoln made in the Second Inaugural where he talked about mercy and healing, but in terms of the crucial issues of citizenship for the formerly enslaved and the question of Black voting rights, nobody knew where he was going to go. Johnson started well in the sense that he had a lot of goodwill from the Republicans, Lincoln’s party, because he had said over and over during the war that treason is a crime and must be punished. At the end of the war Republicans and particularly the group known as “Radicals,” who today might be considered progressives, were heartened by Johnson’s theoretical stand.

The problem was that when Johnson took office, Congress was not in session. A few congresspeople went to Johnson to say, we should have a special session to deal with the problem of the South—what are we going to do with the eleven seceded states, now that the war is over? Johnson said, No, I don’t think we’ll have a special session. He took on the mantle of Reconstruction, or reconciliation, for himself and that was outrageous because to Congress falls the disposition of who may be seated in the House and in the Senate. So right away—forgetting the other issues of representation, citizenship, and voting rights—you’ve got a struggle between the legislative and the executive branches of government.

LHL: He usurps the power of the legislature.

BW: That’s what they thought.

LHL: He says, I will decide under what terms the Southern states will be readmitted.

BW: He thought he was doing well. And there were many, certainly in the Democratic Party, who were very glad that he was taking this role and using executive orders—and that he had pretended to use Lincoln’s plan of Reconstruction. He was pretending to follow in Lincoln’s footsteps because that was a politically expedient thing to do.

LHL: What were the policies that he approved and put into effect?

BW: First of all, Lincoln had said that the seceded states hadn’t seceded because secession is illegal, and therefore they couldn’t have seceded. Lincoln talked about our “erring sisters” and wanting to welcome them back. And when he was asked if secession was legal or not and are they welcome back, Lincoln basically said it’s an academic question and pushed it aside. But Johnson made that the center of his policy.

Very outspoken representatives like Pennsylvania’s Thaddeus Stevens said that to say secession is illegal and therefore the states didn’t secede is like saying murder is illegal and somebody who kills somebody didn’t do it—it makes no logical sense. So Johnson went forward and welcomed the seceded states back. He said that they could be seated in Congress. Congress didn’t let that happen, and he began pardoning at an enormous rate Confederates who, by proclamation, wouldn’t have been allowed to take government office or vote. He gave very lenient terms for these states’ readmission, saying renounce what you’ve done, embrace the Thirteenth Amendment, abolish slavery, and then Confederates who had served as high-ranking officers or who had more than a certain amount of money were re-enfranchised.

LHL: Essentially, he’s reversing the verdict of the Civil War. The Southerners who take power in the state legislatures in the South are former Confederates, and they retain their hostile attitudes toward the Black freedpeople.

BW: Absolutely. A number of northern journalists as well as the writer (and later senator) Carl Schurz went down to the South on fact-finding missions or tours. What they found were appallingly supremacist attitudes that for all intents and purposes seemed to re-enslave the Black people of that region. Shortly after Johnson took office, because of his lenient policies and because former rebels were now in office, something called Black Codes was passed that prevented the Black population from marrying, serving on juries, traveling freely, making contracts, basically doing much of anything. These were the terms on which the South was rectifying itself and, as I said, reinstituting slavery by another name. Of course, the North and the Radicals, but also moderate Republicans, were horrified by this, as were many Union generals. Even if they hadn’t been abolitionists, they were appalled by the conditions they were finding in the South. They realized that the fruits of the war, the labor of the war, the blood of the war, was shed in vain.

LHL: There were lynchings of Black people.

BW: There were murders, absolutely. I itemize in horrific detail so many individual cases of murder. The way the South and some in the Northern press dismissed it was to say that these are isolated incidents. When you tally up the isolated incidents, it’s horrific. Then in some cities, notably Memphis and New Orleans, what were called riots were basically wholesale slaughters of Black people.

The other thing that’s important to underline in terms of Johnson’s policies and his placing of his own people in governorships is the question of representation in Congress, which is partly why even moderate Republicans and many Union generals are horrified at what’s happening. The Constitution said that enslaved persons were three-fifths of a person. It changes the nature of representation when you count that population as a full person—it means that the South has a larger population. If the people who are being counted can’t vote, then they’re being counted for representation but the people who are going to represent them are the very people who want nothing to do with them. There were arguments about why you would enfranchise a Black man when you wouldn’t enfranchise a white woman who can read and write. Those arguments fall short when you think of the fact that if you have more Southerners than those represented in the House of Representatives, you’ve got the same situation that caused the war in the first place.

LHL: You have chaotic turmoil right away in the summer of 1865. When Congress finally does meet in December of that year, the opposition to Johnson begins to assert itself.

BW: It begins slowly to assert itself. It’s interesting that this particular period is a three-year period: it’s both very long and very short. It’s very long in that what brought us to impeachment is a slow boil. It wasn’t as if Congress decided that we’ve got to get rid of this guy, that he’s turning back the clock. They said, How are we going to best deal with this person who seems to be autocratic? Should we give him the benefit of the doubt? Who should we send to talk to him? Congress was trying very hard, from my point of view, to work with Johnson and to talk with him about, for example, civil rights legislation.

There was a man in Congress named Lyman Trumbull, who is basically not known to us now, and he was a moderate. He thought he was working with Johnson on civil rights legislation. We’re not even talking about the Fourteenth Amendment—just how to make people citizens in order to protect them and give them due process. It seems pretty low-level. A moderate Republican, in some sense a conservative, was willing to do that. Trumbull thought Johnson had signed on, and some of Johnson’s Democratic allies thought he should sign on to this. It just buys goodwill. When the legislation was passed in Congress, Johnson vetoed it. And people like Trumbull were shocked and thought, What is he doing? We’ve tried to compromise. We’ve tried to give him an olive branch, and he consistently seems to throw it away.

LHL: The three years are between December 1865 and the impeachment trial in 1868. What is the distinction between moderate Republicans and Radical Republicans? And who were some of the leading voices among the Radical Republicans?

BW: There are two names that may still be familiar to a contemporary audience. The leader of the Radical Republicans in the House was Thaddeus Stevens. He represented Pennsylvania. In the Senate was Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner. Those two can be used as figureheads for what were called the Radical Republicans even during Lincoln’s administration. They were the representatives who wanted to push Lincoln toward a more abolitionist stand early on in the war. They wanted the war prosecuted to free the slaves, not just to save the Union. After the war, people like Stevens thought this postwar period was an opportunity to reframe the country by, for example, taking the land that white planters had owned and dividing it up into smaller pieces to allow poor whites and newly freed Black people to have some of this land. That would break up the oligarchy, as it was called. That was the vision of the Radical Republicans.

LHL: You can have the freedom to vote but if you don’t have some sort of property behind it, you don’t have much.

BW: These people had absolutely nothing. Men like Stevens believed that because these people had worked on the land they, in a sense, owned the land ethically and morally if not in terms of legal contracts. Moderate and more conservative Republicans were debating whether this population should be enfranchised or not. They certainly believed in citizenship, which was part of the antislavery movement that started the Republican Party. But people were divided about how we should move forward in the country.

After the impeachment, after ’68, during the Grant administration, the Republican Party actually did split between what was then called liberal Republicans, what I’m calling moderate and conservative, and the former Radicals. The liberal Republicans became the Republicans that we know of today. Going back, the question for everyone was, How do we let these states back into the Union?

When Congress met in 1865, a number of representatives were sent from various states in the South. One was the vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander H. Stephens. There were a couple of Confederate generals. They went to Washington to take their seats and Congress decided not to call their name on roll call. That was the first battle. The second battle begins to form around legislation like civil rights or the continuation of what was called the Freedman’s Bureau, which was set up toward the end of the war for refugees and former slaves, to help them with education, land, possibly jobs, in order to resettle the country. It needed funding and when that legislation was passed, Johnson vetoed it. Civil rights legislation was passed; Johnson vetoed it. Frederick Douglass and a delegation of Black men came to see Johnson and lobby for the vote. Johnson was quoted as saying, “Those damned sons of bitches thought they had me in a trap.” He was becoming more and more vicious—and certainly obnoxious.

Congress then decided it wasn’t going to get anywhere with legislation. Lincoln had realized legislation wasn’t going to be good enough because legislation can be overturned. They needed an amendment, so the Fourteenth Amendment came, which is due process and citizenship. But Johnson is against the Fourteenth Amendment.

LHL: Johnson is famous right from the beginning for having said, “This is a country for white men, and, by God, as long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men.”

BW: I was withholding that for a little bit to make him a more complicated figure. He stands up against secession and then starts slowly pushing back at this legislation. But the fact of the matter was, yes, he believed that. But he wasn’t alone. Let’s face it, there were other people who believed it. What’s interesting is that there were men in Congress pushing against him and that view, such as Thaddeus Stevens, who said this country is based on equality of all people. They found this reprehensible. Underneath all of these questions about representation, succession, civil rights is the question of race. That is what’s brewing all the way through and what is at the heart, from my point of view, of impeachment. But I don’t want to say that up front because there are legislative fights that are essential.

LHL: These passions boil and bubble for three years. What is the incident that moves things toward impeachment—the Tenure of Office Act? Explain what that is and when that happens.

BW: The Tenure of Office Act was of dubious constitutionality because what it more or less said, and I can’t quote it directly, was that a civil officer whose position has been confirmed by the Senate cannot be fired by the president unless the Senate approves.

Some people feel that it was passed to ensnare Johnson. It wasn’t passed to ensnare him and therefore impeach him. It was passed to protect Stanton, who had been the secretary of war under Lincoln and who along with Grant or Sherman or Lincoln himself has to be credited with the Union victories, because he was instrumental in organizing the railroads and organizing the troops. He was a very important person. Johnson had kept many of the people in Lincoln’s cabinet, and he had kept Stanton. Over time, Stanton began to really despise Johnson for what he was allowing to happen in the South because Stanton was secretary of war. He protected the military, which was also protected by Grant.

That’s important because in the summer of 1867, Congress passed several of what were called Military Reconstruction Acts in order to protect Black men going to the polls and white Republicans voting. There had been so much violence in the South. One of the Reconstruction Acts actually enfranchised the former Black slaves and free Black men in the South, but they might not be allowed to vote. Stanton was protecting the military, which was protecting the polls and making sure that these people who had formerly been disenfranchised were now able to register. Johnson wanted to get rid of Stanton because Johnson wanted to undo these laws.

To get back to the Tenure of Office Act, Congress passed the act, which theoretically prevents Johnson from firing Stanton. But Johnson fires the secretary of war in direct violation of this act. I won’t get into all the details, but he basically violates the law. And at that particular juncture, when Congress wants to keep Stanton in office and Stanton himself won’t even leave the office, it’s enough to actually bring the pot to boil over. In other words, the House votes overwhelmingly to impeach President Andrew Johnson because it was easy to see he broke the law. He not only was flaunting Congress, he was in direct violation of them.

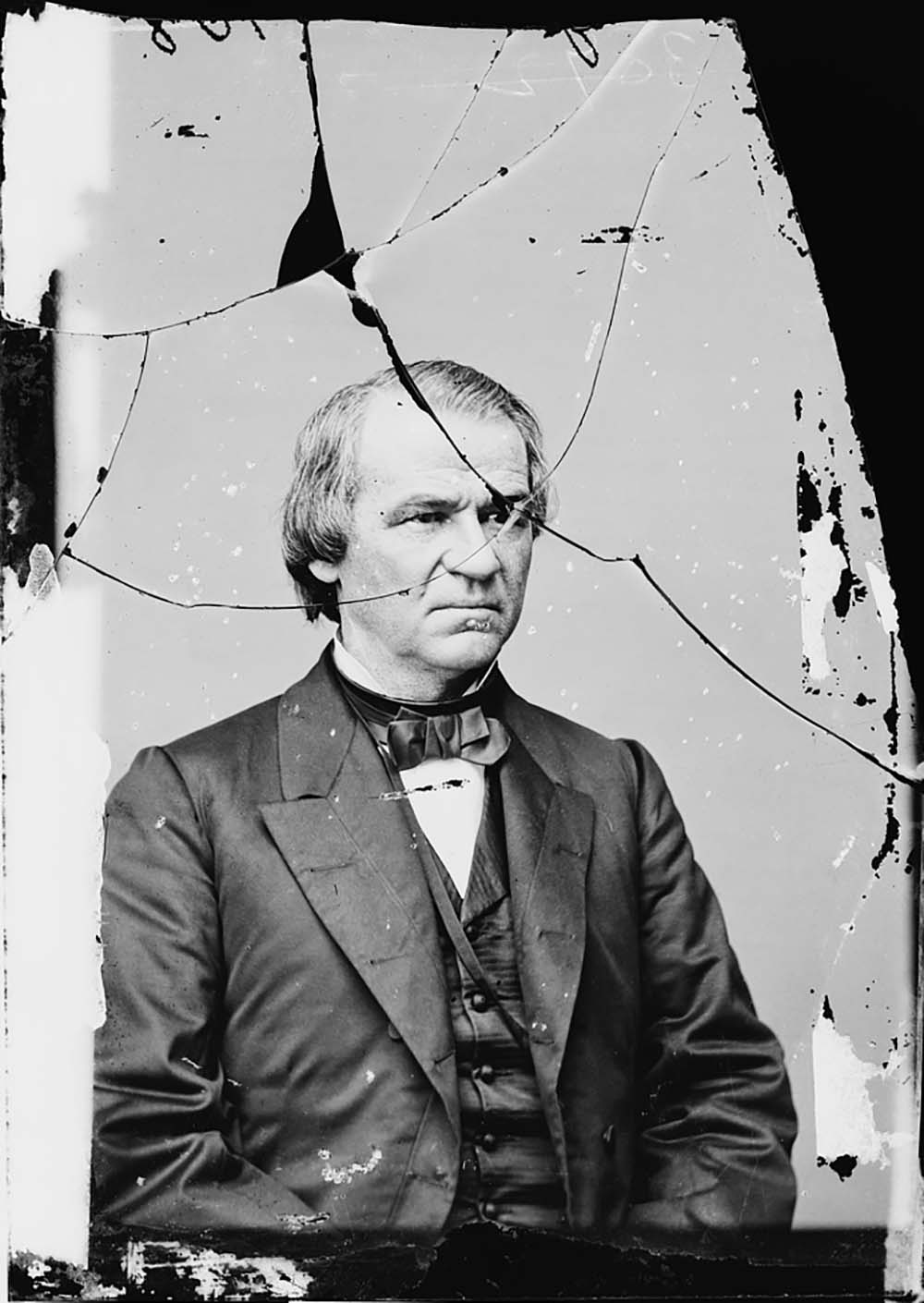

LHL: Before we start the trial, describe in some detail the character and personality of Johnson.

BW: He was considered in his own time in Tennessee as a demagogue. He loved speaking, he loved talking on the stump. He came, like Lincoln, from poverty. He was self-made in the terms of the nineteenth century, pulling himself up by his own bootstraps. He was able to change classes, insofar as you can in the South, through politics, and he was very single-minded. That was a heroic quality when it came to standing against secession. But that same single-mindedness, if you turn the dial a little bit, is a kind of obstinacy.

LHL: He’s stubborn and obstinate.

BW: As Charles Sumner called him, “ignorant, pigheaded, and perverse.”

LHL: He didn’t know the alphabet until he was twenty years old, right?

BW: I think that’s an exaggeration. But he was completely unschooled. He was an autodidact. But he firmly believed, kind of poignantly and horribly enough, in the Constitution. His reason for not wanting the South to secede was that he read the Constitution as protecting slavery, so slavery was better off within the country. It was endangered if the South left and in fact, he was right. He was also a man who believed that if he could take his views, take his feelings, take his bitterness to the people—who he called “my people”—and speak directly to them, then everyone would understand him. Even during his impeachment trial, he wanted to go and make his case directly to the people. He wanted to speak in the Senate. His lawyers, who were quite brilliant, muzzled him. They said, You better not. For the past three years, when he had been going around making speeches, people thought he must be drunk. He really wasn’t.

LHL: He was not too different from Trump’s Twitter.

BW: It’s a good thing that in the 1860s there was no such thing as Twitter. It’s the same sort of uncensored, off-the-cuff, angry vituperation and degradation of other people. When Johnson was campaigning against the Fourteenth Amendment, he would say things like, Hang Thad Stevens, hang Charles Sumner, hang Wendell Phillips, who was a well-known, outspoken radical and formerly an abolitionist. It’s outrageous when you think about it—he’s calling for their execution. It’s hardly decorum and if you associate, which I don’t know if people do, the nineteenth century with decorum and long dresses—this is not exactly etiquette, it’s abuse.

LHL: Washington in those days was as much of a swamp, if not more, as now.

BW: It was literally a swamp. There was malaria and it was dusty and dirty, and there was mud in the roads.

LHL: But also corruption on both sides.

BW: Yes, of course there was corruption. Corruption is not new to our government, I’m sorry to say. Grant’s administration was tarred with the corruption brush, but certainly there was much more corruption. Johnson, it’s always been said and it’s probably true, was honest in that way—I don’t think he took bribes directly.

LHL: Impeachment is February 1868. First is the impeachment in the House and then the trial in the Senate.

BW: It’s a complicated thing. Recently impeachment has been on everybody’s mind and in the papers all the time. It’s really a twofold process. The vote to impeach happens in the House and you need fifty percent of the House. But you need two-thirds of the Senate to acquit, and the trial takes place in the Senate.

The Constitution, which gives broad outlines of what is an impeachable offense and how it should be tried, doesn’t give a lot of information about how this process should be executed. It says that the chief justice shall preside over the trial in the Senate. The chief justice in 1868 is a man named Salmon Chase. He’d been Lincoln’s treasury secretary. He was formerly a Democrat and had been a well-known anti-slavery person back in his day in Ohio. But he wanted to be president. He had run against Lincoln, and he still had his eye on the prize, which means there’s a conflict of interest right at the top, in the trial itself.

Then there are the questions of who’s going to be able to speak, who’s going to be able to call witnesses. All these issues have to be hammered out. It takes a few weeks because the Senate has to decide if it’s still a Senate, which is a legislative body, or if it’s now a court. If it’s a court, there are different legal rules.

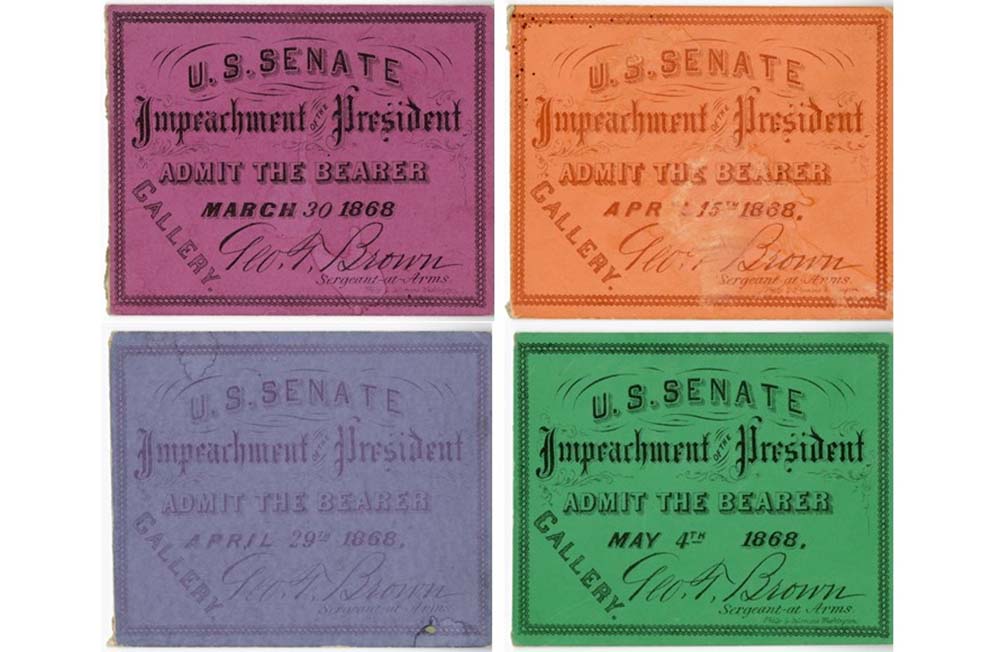

LHL: It’s also a big popular news event. Everybody wants to be there.

BW: They were giving out tickets because everybody in Washington wanted to go, and people came in from other places to attend this trial. In a sense it was the trial of the century, in a century with a lot of trials. There were color-coded tickets. A senator got a certain number of tickets, and you might have green for Monday and red for Tuesday. The Capitol Police were around the Senate in all the doorways, checking tickets and making sure nobody had explosives. This is in 1860. It’s kind of remarkable when you think about it. And, of course, journalists were all over the place. They were rubbing elbows and pushing each other into the galleries. It was a big event.

LHL: Was Mark Twain there?

BW: Mark Twain was there for a little bit but then he left town. I think he had enough of direct politics. He was a wonderful writer and an early radical, from my point of view, and a terrific reporter with a real jaundiced eye and great sense of humor. He really liked Thaddeus Stevens, but he was surprised that Congress finally voted to impeach because he thought they were all moral cowards for waiting this long. They waited for Johnson to step on a statute, when to people like Stevens, Sumner, or Twain even, Johnson had so clearly abused power that he should have been impeached far earlier. But you couldn’t get the votes.

LHL: Among the journalists is Georges Clemenceau, a young French journalist who subsequently becomes the premier of France.

BW: During World War I. It’s incredible.

LHL: Anthony Trollope is also there. Describe Thaddeus Stevens briefly. He’s the most eloquent. He’s ill and actually has to be carried in a chair.

BW: He’s very ill by this time. Stephens had been a long-standing, outspoken member of the House of Representatives. There’s a character in The Birth of a Nation that was based on Thaddeus Stevens. It’s supposed to be based on Stevens for two reasons. He had a clubfoot and had to wear a special boot. He walked with a limp. Also Stevens had a mixed-race, then called mulatto, housekeeper who may have been his mistress. He’s portrayed in Birth of a Nation and at that time in history as a diabolical, fanatic person whose clubfoot was a sign of the devil.

He, in fact, was an outspoken, frank, farseeing visionary who wanted the war prosecuted to free the slaves to make a more just, equal country. He had fought very hard within Congress for many years to make that happen. Now he was at the final trial of impeachment of Andrew Johnson. He didn’t speak very much by that time because it was difficult for him. But he was there, and he was one of the firmest impeachers because when the first nine articles of impeachment were drawn up, he thought they were drawn too narrowly. In other words, they focused too much on the Tenure of Office Act. He wanted the larger issues, those having to do with abuse of power and inequities. He wanted those issues to be the ones that would finally bring Johnson down. And when Johnson was acquitted, which is another story, he was not heartbroken but dismayed and not surprised by the outcome.

LHL: How did the impeachment vote in the House work?

BW: Wendell Phillips, a longtime abolitionist and silver-tongued orator, standing outside of the machinations of Washington, always watching what was going on, said both cynically and realistically that he didn’t think the impeachment vote in the House would have happened if heads hadn’t been counted in the Senate and it hadn’t been guaranteed that Johnson would be convicted. The fact that he wasn’t came as a surprise to many, because I think it was assumed that the votes were there. But it was a fraught political time. We’re not far away from the national conventions. The Republicans are looking toward ’68 and to put Grant in office. That’s one issue that’s important to them. The second issue is that if Johnson were removed from office, there was a senator named Benjamin Wade who would then become the sitting president during this interim time. There were many Republicans, especially moderate Republicans, who were deeply afraid of Wade. He had been a longtime abolitionist, a supporter of women’s suffrage, a longtime outspoken progressive. They didn’t want him in office and to have Grant saddled with him as vice president.

The seven Republicans who voted to acquit Johnson were wobbly; they had mixed motives for sure. The person who is often singled out is Edmund Ross of Kansas, who cast the deciding vote to acquit Johnson. John F. Kennedy in his 1956 book Profiles in Courage singled Ross out in a chapter as a courageous man because he cast the deciding vote to keep Johnson in office when these so-called diabolical radicals like Thaddeus Stevens from Birth of a Nation—not the real Thaddeus Stevens—were trying to push him out. In fact Ross got a lot of favors for doing what he did, and he really didn’t want to lose his seat. After the vote he kept importuning Johnson for lots of different favors. There was a lot of money and favors that were changing hands.

LHL: The vote was thirty-five to nineteen. If there had been thirty-six, that would have been two-thirds. The nineteenth vote is an important one.

BW: It was a very important one. Nobody knew until the last minute. There were operatives sending telegrams saying, We think we have it in the bag. There was another very outspoken, colorful character named Benjamin Butler, one of the members of the House who prosecuted Johnson, who said after the vote was taken, it’s interesting that the opposition had just enough to keep Johnson in office. He launched an investigation after the acquittal to try to find out what happened, but nobody was really going to talk.

LHL: Let’s now come to the last three pages of your own book and your conclusion. You say that in 1868 the situation was far more serious than those surrounding Nixon’s and Clinton’s impeachments. And you say that although it failed, it also worked.

BW: Johnson kept his job. That’s absolutely true. But it’s also true that a representative group believed that it was preferable, even necessary, to impeach Johnson and maybe convict and remove him from office. It was most necessary even if he was acquitted because it makes a statement about the way the country needed to rethink itself and its future. Moreover, what impeachment implied, and I think this is often lost, was that it was orderly. It was mandated by the Constitution. It wasn’t a partisan, hysterical moment in American history. It was a last-ditch effort to inspire the country, to suggest that if we make mistakes, there are ways of rectifying those mistakes, and we can rectify them without a war. It also offered a warning about the policies that Johnson and people like Johnson wanted to take and what that implied for the future. In a sense I think that the process itself worked. These people who undertook impeachment knew what the consequences might be and were willing to take those consequences because of a long-term commitment to a better, more perfect union.

LHL: But we still haven’t reached that point—when we get to the election of 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes keeps in place the Johnson policy.

BW: He restores it in a sense. He basically boots the military out of the South. From my point of view, the impeachers had been working very hard to prevent that from happening. Think of what they did accomplish: the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, civil rights legislation was passed, the Reconstruction Acts were passed. That’s remarkable. And they called Andrew Johnson to task. I think that’s really important because they were making a statement. They said, We’re going to call him to task. We know we may not win. We know we may not get what we want but that should not prevent us from speaking out and speaking loudly about what we represent. He doesn’t have to represent the future. We can represent an alternative.

LHL: Final question, which I can’t help asking you given our present circumstances in Washington, would you say the same thing about the impeachment of Mr. Trump?

BW: I should be prepared for this question and I never am. I think it’s because I’m basically ambivalent. Part of me thinks yes, absolutely, because it makes a statement. It makes a stand. Imagine what it would be like to not try to impeach Donald Trump if he wins in 2020 and nothing was done to alter his course. By the same token, I am mindful of a situation now that didn’t exist in 1868. In 1868 the Republicans assumed that they had the votes. We can’t assume now that we have the votes in the Senate. Wendell Phillips was right: those people weren’t going to do it if they didn’t think they could win. But as a kind of pyrrhic statement, perhaps, go ahead.

There are two different lines of thought. Even though we talked about Stevens as this enormous and powerful radical, he was a pragmatist. Ultimately, he was very concerned with getting as much possible and making compromises. When there were compromises in the Fourteenth Amendment—he wanted to go much further—he was willing to vote for it. Charles Sumner, on the other hand, was a purist and an idealist. He often seemed to be an obstructionist because he wanted to prevent legislation from passing that wasn’t perfect. It’s between those two poles that I find myself falling: whether to be along the lines of the so-called pragmatists or along the lines of Sumner and the purists.

Thanks to our generous donors. Lead support for this podcast has been provided by Elizabeth “Lisette” Prince. Additional support was provided by James J. “Jimmy” Coleman Jr.

Subscribe to The World in Time on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, SoundCloud, and Google Play, as well as via RSS.