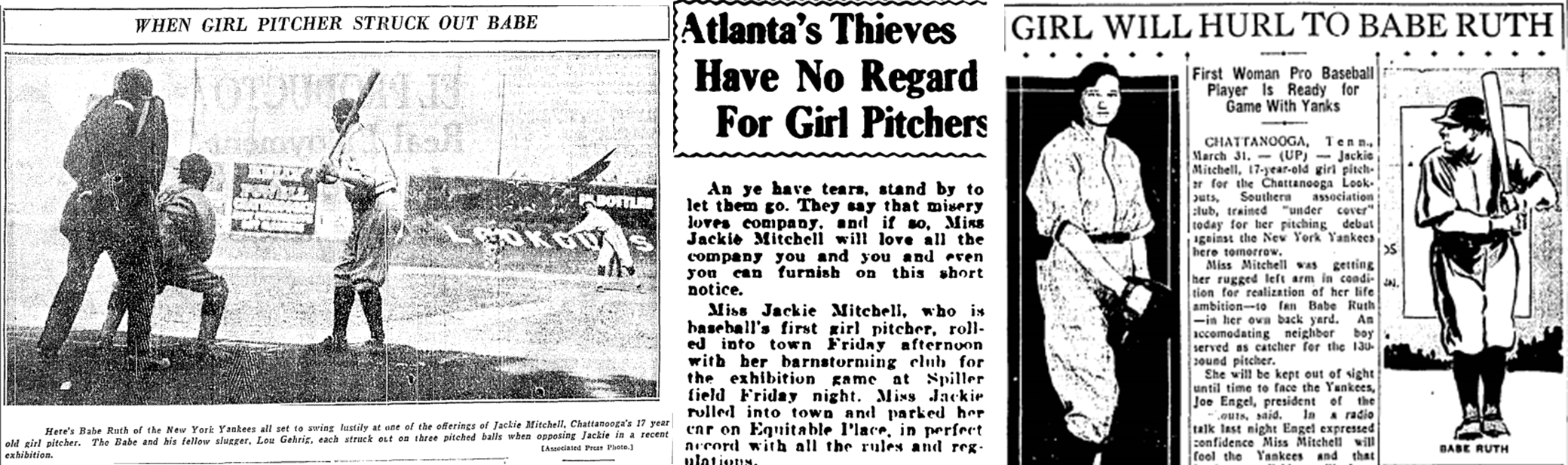

Headlines about Jackie Mitchell from the Chicago Daily Tribune, April 6, 1931; the Atlanta Constitution, June 27, 1931; and the Austin Statesman, March 31, 1931.

On the first pitch of that April 1931 game, Chattanooga Lookouts pitcher Clyde Barfoot gave up a double to New York Yankees outfielder Earle Combs. Then Lyn Larry singled to centerfield, bringing Combs home. Now Babe Ruth, who had led the American League the year before in both home runs and slugging, was coming to bat with no outs and a man on base.

Ruth approached the plate with “a wry smile playing at the corners of his mouth,” an Associated Press reporter wrote. The crowd of four thousand at Engel Stadium began cheering wildly. Like the smiling Ruth, they knew what was coming.

Lookouts manager Bert Niehoff walked to the mound, took the ball from Barfoot, and brought in his new pitcher—a seventeen-year-old left-hander named Beatrice Mitchell. Everybody called her Jackie.

Mitchell had first made national news two months earlier, in a short article that ran in sports pages around the country: “Enrolled in a new baseball school conducted at Atlanta, Georgia, by Norman (Kid) Elberfeld, former major and minor league figure, is Miss Jackie Mitchell, age seventeen, a left-handed pitcher.”

At the time, the sports media’s interest did not extend beyond that one sentence. For decades, women had been playing baseball in college intramural teams and novelty barnstorming clubs such as the Bloomer Girls, named for the billowy trousers they wore during games. Some women had even made it into men’s semipro leagues. It was hardly newsworthy that a girl would participate in America’s pastime.

But then, beginning the last week of March 1931, Mitchell’s name reappeared in the papers. Lookouts owner Joe Engel announced he was adding Mitchell to his team’s pitching rotation. Her first appearance would be in an exhibition game against the New York Yankees.

Mitchell was scheduled to make her first public appearance at Engel Stadium on March 31, where she was supposed to pitch for the press. But much to waiting fans’ disappointment, Engel kept her out of the public eye until the game and showed her off to reporters at a backyard pitching session instead.

It was at this point Mitchell’s origin story began to trickle into the papers. Her parents encouraged her to play sports from an early age—doctor’s orders after she was born premature. When she was seven years old, her family lived in a Memphis duplex beside future Hall of Fame pitcher Charles “Dazzy” Vance, who was then playing for the Memphis Chicks. When Vance saw his young neighbor playing ball with the boys and noticed she was left-handed—a coveted trait for a baseball pitcher—he taught her to throw.

As she grew older, Mitchell showed promise in tennis, swimming, and basketball. She thought about becoming an aviator like Amelia Earhart. But baseball remained her first love. When the family moved to Chattanooga, Mitchell joined the Englettes, a girls-only team owned by Engel and managed by her father.

Watching her pitch to a “boy friend” who agreed to serve as catcher, sports scribes noted Mitchell’s “odd side-armed delivery” but complimented her speed, control, and curve. They asked if she was nervous. “There is no use to get nervous over a ball game when I have been playing ball nearly all my life,” she said. “I will just go out there and do my best, and I believe I can fool the Babe.”

During his thirty-five years with the Lookouts, Engel became known for his vaudevillian antics. He once traded a slumping shortstop for a turkey, which he cooked and served to sportswriters. He staged a phone call to Adolf Hitler and held an “elephant hunt” in the outfield with papier-mâché pachyderms. Another time, he lured a newly recruited Native American player inside a teepee he’d erected on the pitcher’s mound. Engel emerged a short time later, bellowing “Custer’s revenge!” and holding a butcher knife in one hand and a “scalp”—actually a dark-colored wig—in the other.

But all that would come later. Engel’s first big stunt would be pitting a teenage girl against the Yankees’ Murderer’s Row batting lineup.

Newspapers across the U.S. picked up the story but remained skeptical. Writers pointed out the game was scheduled for April 1, a sure sign the whole thing was a prank. When a photographer telegraphed The Sporting News and offered to shoot Mitchell’s contract signing, the receiving editor thought it was a joke: “Quit your kidding. What is Chattanooga trying to do, burlesque the game?” The photographer wired back to assure the newspaper he was not kidding, but the editor was not convinced. “Yeah! Presume Al Capone or Charlie Chaplin will be catcher. In sending any more wires please pay for them so I can enjoy the laugh.”

The game would not take place on April Fools’ Day, however. Cold weather forced Engel to postpone until the next day. The delay did nothing to dampen anticipation. By the time the game began on Thursday afternoon, bells were ringing on teletype machines across the country as reporters filed accounts of the game.

With Barfoot out of the game, Mitchell emerged from the dugout swimming in an oversize flannel uniform, her bobbed black hair tucked under a ball cap. She took the mound, produced a mirror and powder puff, dabbed her nose, laid down her cosmetics, and assumed her stance.

She went into a long windup. A writer for the Baltimore Sun said she looked “as if she was turning a coffee grinder.” Mitchell hurled the ball toward home plate.

Ruth swung and missed.

Strike one.

Mitchell’s second pitch to Ruth was high and wide. The count was even now, one ball and one strike. She delivered another wide pitch. Ball two. Now she wound up again, raising her right foot from the ground and shifting her weight toward home plate. The ball curved toward Ruth, who swung and missed for strike two.

Ruth asked the umpire to inspect the ball. Everything was fine, so Mitchell wound up and threw again. The ball crossed the plate but Ruth did not swing. Strike three. The Great Bambino slammed his bat against the ground and returned to the bench.

She would now face the Iron Horse: the Yankee’s crown prince, Lou Gehrig.

Mitchell’s first pitch against Lou Gehrig came in high. The umpire called ball one. Her second pitch was wide for ball two. Then her third pitch arrived, and Gehrig swung and missed: strike one. He did the same for the next pitch, and the next. “You’re out!” the umpire said.

Jackie Mitchell had struck out two of the best batters in the major leagues. But before the inning was over, Barfoot returned to the mound, and she was sent into the dugout.

The Yankees easily defeated the Lookouts on that April afternoon in 1931, scoring fourteen runs to Chattanooga’s four. But afterward all anyone wanted to talk about was the first inning. Engel boasted he’d already received two offers for Mitchell, including one that put up two players, two dollars, and a box of cigars for the trade.

Two days later, United Press International reporter Foster Eaton published an interview where he tried to get Ruth to admit the strikeouts were intentional. The Great Bambino admitted he had received fifty letters asking if he was going to allow himself to be struck out, but he wouldn’t discuss the issue further. At one point, Eaton asked point-blank if he struck out on purpose. The Sultan of Swat responded with “just a trace of a wry grin.”

In a press conference immediately after the game, a reporter asked Mitchell if the strikeouts were intentional. She did not answer. According to a reporter from the Belvidere Daily Republican of Illinois, she “retorted with a gaze of utter scorn and a contemptuous silence.”

When the Lookouts hit the road a few weeks later, Mitchell stayed in Chattanooga. Engel said she wasn’t up to the task of pitching regularly. “Maybe next year.”

But just a month later, he loaned her out to a barnstorming team run by Kid Elberfeld for a tour of the Midwest and South. She then traveled with the Junior Lookouts, a barnstorming team hastily assembled by Engel to capitalize on Mitchell’s newfound fame.

It was an exhausting schedule. During a stop in Anniston, Alabama, a sportswriter reported Mitchell had pitched forty innings over the last dozen days—an exceedingly high number for any pitcher, let alone a young and inexperienced one. By comparison, Philadelphia’s Rube Walberg pitched more innings than anyone in the major leagues in 1931, throwing 291 innings over an entire season.

Mitchell pitched only one inning that night in Alabama but made quick work of the batters she faced. The Junior Lookouts won 15–11.

Engel put Mitchell on the road again for the 1932 baseball season. Billed everywhere as “the girl who fanned Babe Ruth,” she spent the summer pitching for ball clubs in the South—the Charlotte Bees, the Raleigh Caps, Frank’s Athletics of Newport News, an all-star team in Nashville, among other semipro clubs.

It wasn’t until 1933, after her contract with Engel expired, that Mitchell was able to play for the same team night after night. That July, she signed with the House of David’s baseball team.

The House of David was a cult from Benton Harbor, Michigan, founded by a self-proclaimed messenger from God named Benjamin Purnell. Purnell forbade his adherents from smoking, drinking, having sex, eating meat, and cutting their hair. Men were not allowed to shave their faces.

He had no problem with sports, however, and established a semipro team with cult members. His club, often referred to as “the Bearded Nine,” became famous on the barnstorming circuit for their “pepper game,” a comical routine that sometimes had players fielding balls while riding donkeys.

Mitchell was not required to participate in the cult’s religious activities—or, as papers noted, wear a beard—but did receive $1,000 a month for her services on the mound.

She appeared at the contract signing with a black eye she had sustained in a tryout game in Philadelphia a few days before. “Miss Mitchell is by no means a girl, insofar as her expertness is concerned,” House of David manager (and Hall of Famer) Chief Bender told New York’s Middletown Times Herald.

But Mitchell had not overcome skepticism about her abilities. Although the press warmed to her after the Yankees game, sportswriters were back to ridiculing Mitchell when she joined the Bearded Nine two years later.

Like any pitcher, especially one pitching every night for weeks on end, she had good games and bad games. But no matter how she performed, Mitchell could not win. If she pitched poorly, people assumed she didn’t belong on the mound. If she pitched well, people assumed the opposing team was giving up strikes out of chivalry or novelty.

When she had a good showing in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, a local writer bragged, “The home club did right by ‘Little Nell,’ promptly striking out and going to the bench on easy outs.” In Benton Harbor, Michigan, Mitchell entered the game with one out in the bottom of the eighth inning. Her first batter grounded out to first. The next batter “took three ‘healthy’ swings and sat down as all gentlemen should with a lady in the ‘boss’ role,” reported the local paper, the News-Palladium.

A frustration started to creep into the interviews Mitchell granted. Talking with Michigan’s Battle Creek Enquirer, she complained about having to pitch every day and how the fans treated her. “Sometimes I am booed by the fans whenever I am scored upon,” she said. “Once I pitched seven scoreless innings in six games, then was booed when a team scored a run. That hurt, because the fans in that city did not know that I had pitched well elsewhere.”

Mitchell never made it to the big leagues. Many accounts say that, soon after her game against the Yankees, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned Mitchell from the major leagues because he believed the game too strenuous for women. There are no surviving documents to confirm this story, but an Associated Press brief from 1932 mentions the ban, and Mitchell addressed the issue directly in a 1933 interview with the St. Louis Dispatch. “I believe I could qualify and might be signed by a major league team and might someday get to play in a World Series if Judge Landis hadn’t ruled against my playing in major league ball,” she told the reporter. “He doesn’t give any reason for his ruling, either.”

She left the Bearded Nine after the 1933 season but kept bouncing around the barnstorming circuit. In 1937, at age twenty-three, she signed to play with the Hawaiian All-Stars, another novelty team whose players wore grass skirts on the field. It would be her last season in baseball.

It’s unclear if Mitchell even pitched in her final game. One thing is certain: there was no national press to chronicle the play-by-play. No editors waited by their teletype machines to find out the result of the game. There was no Babe Ruth; he had retired from baseball two years prior. There was no Lou Gehrig, who was still a star on the Yankees roster but in two years’ time would deliver his “luckiest man” speech and leave the game forever.

After hanging up her glove, Mitchell went to work at her father’s optometry office until his death fifteen years later. She married Eugene Gilbert and took his last name, yet for years she still received mail addressed to Jackie Mitchell and “The Girl Who Struck Out Babe Ruth.”

Neither Ruth nor Gehrig ever admitted to striking out intentionally in Chattanooga, although Engel, ever the provocateur, claimed the game was a hoax in a 1955 letter to a newspaper columnist: “Between you and me, she couldn’t pitch hay to a cow, but she looked mighty pretty in the regulation league uniform I had made for her, and I had a record attendance that day.” Engel’s statements hardly prove anything, though, considering his propensity for self-promotion, the dozens of batters Mitchell would later strike out, and the telltale bagginess of her ill-fitting “regulation” uniform in that game against the Yankees. Mitchell never wavered in her conviction that her strikeouts were legitimate. “She firmly believed she did what she did,” says David Jenkins, former baseball writer for the Chattanooga News-Free Press, told me recently.

A local TV station later discovered Mitchell had a 35-millimeter newsreel film of her famous game but no way to watch it. They sent the film to a restoration service in Washington, DC, which transferred the images from the shriveled nitrate to a VHS tape. She watched her seventeen-year-old self lob pitches to Babe Ruth and saw the American icon swing and miss. To her, it was undeniable proof of her achievement. “I’m so proud…that I’ve saved that film all these years. It convinces people that Babe Ruth didn’t intend to strike out,” Mitchell told Jenkins in 1985.

Jackie Mitchell died on January 8, 1987, at the age of seventy-three. She had no survivors. Her husband had died in 1974, and the couple never had children. Jenkins wrote a short obituary in that day’s News Free-Press, recalling a conversation where he asked if she ever tired of talking about her most famous game. Mitchell said she did not. “It’s a wonderful feeling knowing you can relive the moments. Sometimes I wish I could go back to that time.”