Judith with the Head of Holofernes, by Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1530. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1911.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

Sixth-century Francia would seem to have been a terrible time and place to be a woman, particularly one with political ambition—even harder to be a female monarch feuding with another female monarch. But for two Frankish queens, Fredegund and Brunhild, this was exactly the case.

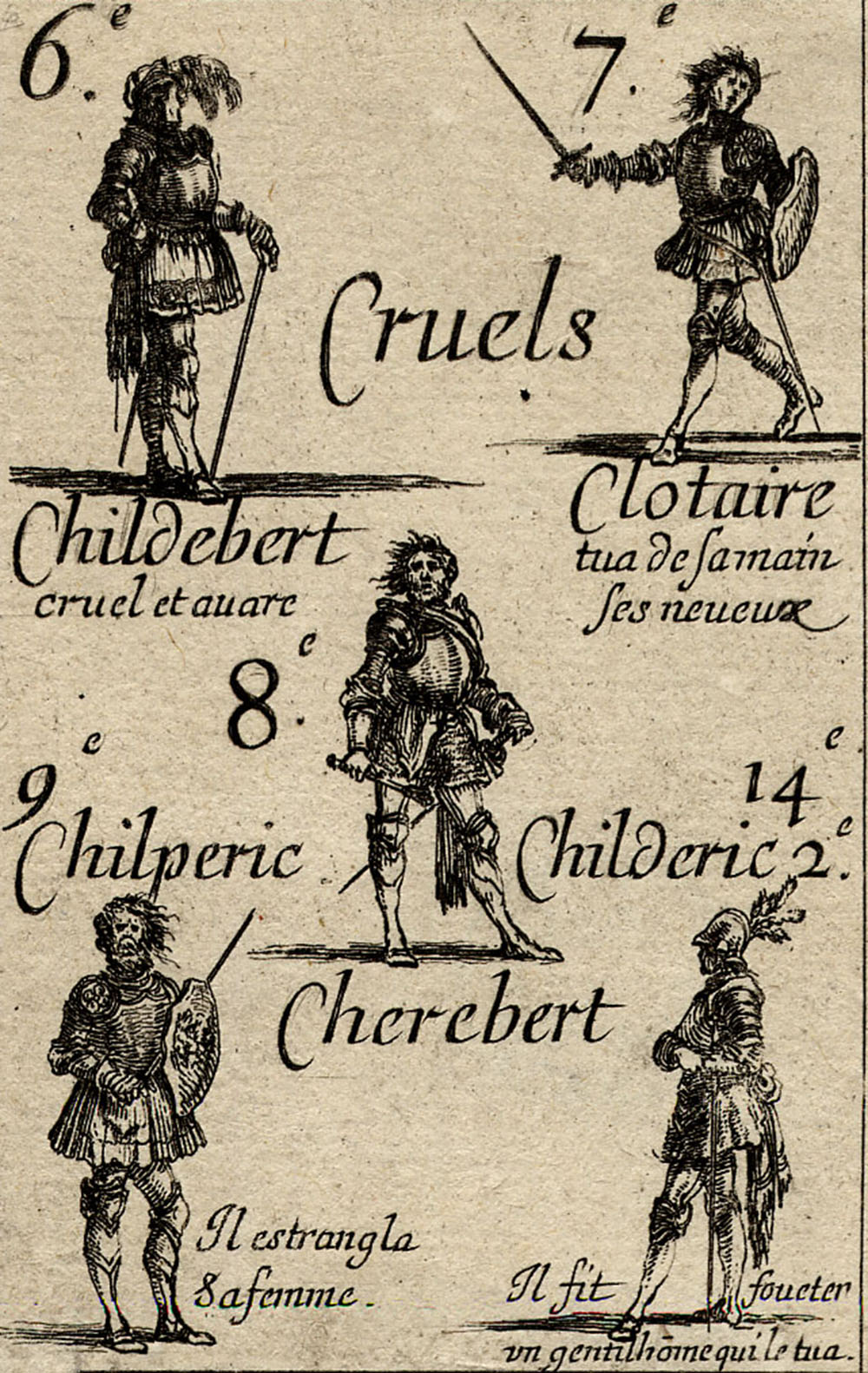

The Merovingian dynasty, into which Fredegund and Brunhild had married, was known for its frequent kidnappings, brawls, assassinations, and wars, as the Merovingians did not practice primogeniture and thus had no established line of succession. And unlike the Roman empresses before them and medieval queens who followed, queens of the reigning Merovingian dynasty were never coronated in their own right. They were queen only as long as their marriages lasted—and divorces, annulments, and convenient deaths were not uncommon. Even worse, Salic law—which specifically barred women from inheriting the throne—had been established at the beginning of the century. Still, over the course of less than a generation, this misogynistic world saw women go from having no formal role in secular public life to controlling the empire.

Yet this coup-like accomplishment is often overshadowed by the relationship between the two queens, a fierce rivalry that had international implications and brought Western Europe to the brink of full-scale war. The origin of their grudge match is commonly traced back to a morning in 568 when a newlywed queen was found strangled in her bed. By the time the dust cleared, ten kings were dead, one queen had been executed in a spectacularly brutal fashion, and the son of the other queen ruled over a finally reunified Francia.

This history does not begin with women in charge but—as is so often the case—with competitive men at odds with one another. When Clothar I, king of the Franks, died in 561, his sons split the empire into four separate kingdoms. Then, when one brother died, the number fell to three, with the city of Paris held in common. Guntram ruled Burgundy, Chilperic ruled Neustria, and Sigibert ruled Austrasia.

Sigibert quickly saw an opportunity to set himself apart from—and above—his brothers. According to Bishop Gregory of Tours, “King Sigibert observed that his brothers were taking wives who were completely unworthy of them and were so far degrading themselves as to even marry their own servants.” Though Guntram had many low-born mistresses, the main issue for Sigibert was their third brother, Chilperic, who was involved with a palace slave named Fredegund, who had already managed to have his first wife deposed and sent off to a convent.

Sigibert wished to gain the upper hand through a strategic partnership, hoping to further legitimize his reign through a marriage alliance, and he asked for the hand of Brunhild, the daughter of Visigoth king Athanagild. Brunhild was an elegant, well-educated princess and came with a considerable dowry. Sigibert’s offer was accepted; the two were married in a lavish ceremony to great acclaim in 567.

But Chilperic was not to be so easily outdone. Ever competitive with his brothers, he promised to forsake his other wives and mistresses, including Fredegund, and negotiated for the hand of Brunhild’s sister Galswintha. A second lavish marriage took place later that same year, in Rouen.

The double weddings of 567 seemed to promise peace—two brothers of two neighboring kingdoms marrying two sister-princesses and securing an important alliance with the Visigoths in Spain. But in less than a year, Fredegund was back in Chilperic’s bed, and, in turn, Galswintha wanted out of the marriage. She asked if she could leave her dowry behind and return home. Chilperic refused and, so Gregory tells, “made ingenious pretenses and calmed her with gentle words”—then, soon after, “ordered her to be strangled by a slave and found her dead on the bed.” Three days later, Chilperic married Fredegund. The sophisticated princess Brunhild and the former palace slave Fredegund were now sisters-in-law in positions of power that would come to dominate the political landscape of Europe for several decades.

Even by Merovingian standards, the queens’ rise to power was fantastic in its violence and improbable in its plot twists. After the 568 murder of Galswintha, Sigibert and Guntram invaded Chilperic’s kingdom at Brunhild’s urging. The brothers drove Chilperic out and kept him on the run over the next eight years. Finally, they surrounded his forces in Tournai.

Brunhild and Sigibert marched triumphantly into Paris with their young son in anticipation of taking over the entire Frankish Empire. But Fredegund had continued plotting, sending in assassins in a last-ditch attempt to save her husband. Her hired hands attended Sigibert’s victory feast, where they stabbed the triumphant king with poisoned eating utensils. Brunhild and her young son were taken captive. Her political career seemed finished; she was far away from the protection of the Spanish court, which was in no position to negotiate for her release. Yet still Brunhild managed to escape. She went on to conspire with Chilperic’s deposed first wife and then marry one of Fredegund’s stepsons, which allowed her to raise her own army. Brunhild subsequently not only ascended the throne as regent on behalf of her very young son but also convinced the childless Guntram to name her son as his own heir. The effect of all this was that in a short time she machinated herself from being the imprisoned widow of a murdered king to securing claim to two of the three kingdoms of Francia.

But all this did not end the civil war, which dragged on, pitting kingdom against kingdom, Brunhild and her allies against Chilperic and Fredegund. Accounts of the period make clear the former palace slave held power and influence as queen: Fredegund often operated independently of her husband, offering bribes to officials and arranging the assassinations of her rivals, including Brunhild’s husband, Chilperic’s other wives, and her stepson who had married Brunhild. Though Chilperic was the king, he often publicly deferred to her judgment. He once told a nobleman begging for a pardon that he could not act unilaterally but had to wait “until I have discussed this matter with the queen and found some way of restoring you to her good grace.” (Chilperic was not successful, apparently; the poor man was soon executed “at the personal command of the queen” by being beaten across the throat with a piece of wood. His punishment exemplifies Fredegund’s penchant for creative retribution: she was infamous for ordering failed assassins to have their hands chopped off and servants, messengers, and commoners who disappointed her to be stretched on the rack, disfigured, or burned alive.)

Chilperic was assassinated in 584. Despite Fredegund’s reputation for ruthlessness, this move put her in a precarious position, one eerily similar to that of her rival years earlier. Fredegund fled the kingdom for the sanctuary of the cathedral at Paris, taking her four-month-old son and much of the palace’s treasure. But her rival saw an opportunity: Brunhild’s son ordered Paris surrounded, demanding Fredegund be turned over to face justice for the murders of his aunt and father. Yet Fredegund again escaped by negotiating protection from the last remaining brother, Guntram, asking him to “adopt” her infant son. Guntram agreed on the condition that Fredegund step aside. He arranged for her retirement from public life, sending her off to the care of a bishop in Rouen. While in exile, however, Fredegund launched an attempt on Brunhild’s life, framed the royal treasurer for her husband’s murder, and then seized the crown. She had spent sixteen years as a powerful queen consort; now she would rule on her own for thirteen more years as regent for her son, Clothar II.

Brunhild ruled even longer, serving as queen consort for eight years and then regent for three generations—for her son, grandsons, and great-grandson. Even in the brief period between regencies, when she had officially stepped aside, Brunhild’s continuing influence can be found recorded in the annals of the era. When her son negotiates a treaty with Guntram, the third party to that treaty is, of course, “the most renowned Lady Queen Brunhild.” When the Byzantine emperor writes to her son, the response comes back from “Brunhild queen.” And even though she is queen technically of just one Frankish kingdom, Pope Gregory I addressed her as the supreme ruler of the land: “Brunhild queen of the Franks.” This became true enough after Guntram died in 592: Brunhild became regent of the third Frankish kingdom, meaning that all three kingdoms of the Frankish Empire had fallen under female rule.

Fredegund and Brunhild were not the world’s only female regents in the late sixth century. In neighboring Lombard, Italy, the widowed queen Theodelinda ruled as regent; in Byzantium, Aelia Sophia, wife of Emperor Justin II, stepped in as regent when the emperor went mad; and although it is unlikely Fredegund or Brunhild would have heard mention of it, halfway around the world, Empress Suiko was ruling as the Japanese Empire’s first female regent. At the same time, women were in charge of four separate medieval empires.

But dual female rule in Francia was cut short by Fredegund’s death in 597. Even though much of her reign was defined by fearsome battle, she died surprisingly peacefully in her own bed and was buried with great honor in Saint-Germain-des-Prés under a faceless effigy on her sarcophagus lid. Brunhild lived longer, well into her seventies, but her machinations caught up to her, bringing upon her a horrific death. Fredegund’s son Clothar II captured her, paraded her on a camel, tortured her on the rack for three days, and then had her—depending on which account you believe—ripped apart or dragged to death by wild horses. It was a spectacularly brutal means of execution for a queen, a lurid public destruction of a woman. Many believe it unmatched to this day.

In the spring of 588, before the epic and fatal denouement to this tale of two queens, Bishop Gregory of Tours and his friend Felix, Bishop of Nantes, had met with Guntram to discuss a peace treaty. In his History of the Franks, Gregory recounts that after the negotiations were concluded, the men dined, drank, and turned their conversation to the hot gossip of the early medieval world—the bloody feud between Brunhild and Fredegund, by then the other two Frankish monarchs. Was it true, Guntram asked Felix, that he had somehow managed to “establish warm friendly relations” between them?

Gregory drily answered for his friend: “The ‘friendly relations’ which have bound them together for so many years are still being fostered by them both. That is to say, you may be quite sure that the hatred which they have borne each other for many a long year, far from withering away, is as strong as ever.”

Gregory’s history says nothing of how the women would have characterized any of this, leaving us only the thoughts of men sequestered in their own space. So much history—especially history about what women thought—is unavailable and remains simply impossible to know. Accounts that remain, written by men, tell their own story. Gregory of Tours’ account is the only surviving eyewitness narrative of Brunhild and Fredegund’s blood-soaked rule.

It is biased (he conveniently omits the fact that Brunhild helped secure his election as Bishop of Tours), religiously motivated (he often rails against the sinfulness of secular rulers and includes credulous reports of improbable miracles), and incomplete (he died before either queen). In the 660s, fifty years after Brunhild’s death, another chronicle was written, later attributed to a man named Fredegar. It picks up where Gregory’s History left off and narrates the end of both queens’ reigns, though this time with a flattering eye for the heirs of Fredegund, who now commanded the empire. Another fifty years later, a century after Brunhild’s death, the Liber Historiae Francorum synthesized and embellished Gregory of Tours’ and Fredegar’s accounts.

While Gregory of Tours was very matter-of-fact about these monarchs’ gender, the accounts of the queens’ lives composed after their deaths focus unduly on them as failed wives and mothers. Fredegund is introduced as “beautiful, very cunning, and an adulteress,” Brunhild as “a second Jezebel.” Salacious sexual details are added—Fredegund murders King Chilperic after being caught committing adultery with one of his generals, and Brunhild is pointedly said to have seduced many men when she was well into her late fifties.

The chroniclers emphasize the domestic dimensions of their ruthless actions, hinting at an unnatural lack of maternal feeling. Fredegund was notorious for assassinating her stepsons and for coming to blows with her own daughter, once attempting to kill her by slamming her head with the lid of a treasure chest. Brunhild, too, was harshly judged for her actions against members of her own family, in particular her ordering the deaths of her infant great-grandsons. Though the queens’ most brutal actions were not out of line with those of Merovingian kings who came before and after them—including one who bore the name Chlodoric the Parricide—chroniclers express horror, rather than viewing the acts as calculated, common political moves, as may have been done for male rulers. The queens’ hatred for one another was also described in specifically personal terms of love triangles and personal vendettas, cautionary tales about what happens when emotional women wield power.

But no matter what salacious stories might have dominated the historical narratives about them, these queens had inarguable political effect: they consolidated and centralized Frankish control of the region, paving the way for Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire. Brunhild did so through her talents for administration and foreign relations, repairing old Roman roads, including the one once used by Caesar that ran past Alligny-en-Morvan. And she built other infrastructure: in Autun, a hospital, a convent, and church dedicated to St. Martin; in Laon, the abbey of Saint Vincent; and in Bruniquel, a castle. She also competently managed the volatile relationships between the nobles in her court. Once she even “armed herself like a man and rushed into the midst of the opposing forces” to successfully defend one of her ambushed supporters. A skilled diplomat, Brunhild successfully negotiated with the Goths, Lombards, and the Byzantine Empire, and she was instrumental in helping Christianize England. Pope Gregory I praised her contributions to the Augustine mission as second only to God’s.

Fredegund was a competent administrator, noted for her tax reforms. She was celebrated more for her military acumen, though, and was still lauded nine centuries later in Christine de Pisan’s protofeminist Book of the City of Ladies for “the boldness of her deeds in battle.” Shortly after she came to power, Fredegund adopted an ingenious military strategy at the Battle of Droizy. She camouflaged her troops, put bells on her army’s horses, and disguised her soldiers with branches. One enemy sentry, reporting that the woods were moving closer, was laughed off by his companions as a drunk. The soldiers were reassured by the sounds of bells, which they assumed were just cows and horses out to pasture. Fredegund’s troops marched at night and quietly surrounded Brunhild’s forces, pouncing in the morning. The strategy would eventually be immortalized in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, in which it is attributed to a man.

In a subsequent battle, Fredegund’s general and rumored lover was killed. Fredegund stunned her opponents by taking his place, leading the charge while holding her very young son. While Brunhild’s ally Guntram was warding off invading Bretons from the West, Fredegund ordered her men to cut their hair in the signature Breton style and join their raids to further weaken her enemies while maintaining plausible deniability. Her ability to make the most of her considerably lesser forces through the strategies of surprise and disguise would make it possible for the smallest kingdom in Francia to eventually defeat the other two larger kingdoms.

The legacy of these two queens has long been overshadowed by their feud. Scholars have usually fallen in one of two camps: the feud is all important to understanding these two queens, or it is the means by which we willfully misunderstand them.

Contemporary sources often lean toward the latter opinion, choosing to describe animosity between the two queens but making no explicit mention of a personal feud. And although Gregory of Tours specifically uses the Latin word for “feud” elsewhere in his narrative—and even uses it to refer to the actions of another queen he admires—he chooses another word, hatred, to describe these queens’ relationship. This is the same word he uses to describe political rivalries between male clergy and nobles. And Gregory, the only eyewitness to events, who had every reason to hate and smear Fredegund, chooses to blame Chilperic—not the queen—for the murder of Galswintha. But this forces a problem of historical interpretation: if the queens were not engaged in a personal feud, what motivated them to battle so fiercely for forty years?

The answer may lie in the very treaty Gregory of Tours was negotiating with King Guntram during that visit in the spring of 588 where the “friendly relations” were discussed. The Treaty of Andelot refers back to the event that thrust both queens onto the international stage, the murder of Galswintha. Upon her marriage to Chilperic, Galswintha had been given a lavish gift unheard of in the early medieval world: five wealthy cities, Bordeaux, Limoges, Cahors, Béarn, and Bigorre. After her murder, Galswintha’s morgangabe, or bridal morning-gift, passed on to her heir, her sister Brunhild. The treaty specifically mentions the fact that Brunhild’s claim to these lands in Chilperic’s former kingdom is supported by the law: “the Lady Brunhild is recognized to have inherited [these cities], by the decree of King Guntram and with the agreement of the Franks.”

In killing Galswintha, Chilperic had broken an alliance with the Visigoths in Spain in a very public way. And he had then violated the established laws of inheritance, seizing Brunhild’s property as his own. This offers a different kind of intention for Brunhild’s actions: she battled continuously with Fredegund not to exact vengeance but to secure valuable territory. Yet this would run counter to expectations, often carried in narratives about the motions of history, that men scrap over land and money, while women fight over relationships, by which thinking Galswintha’s murder is, of course, cast as a love triangle—the pious wife, the scheming mistress, the seduced king. Brunhild’s response is then understood as the retaliation of a grieving sister.

In this way, interpretations of these two queens’ stories serve, perhaps, as a kind of Rorschach inkblot test, a sort of duck-rabbit illusion. The urge is strong to turn Brunhild and Fredegund into easy foils for one another—virgin/whore, princess/former slave, administrator/warrior. But still lacking a sense of what a prolonged era of female leadership looks like, we don’t, even 1,400 years later, have a lens capable of throwing the lives of these queens into focus.