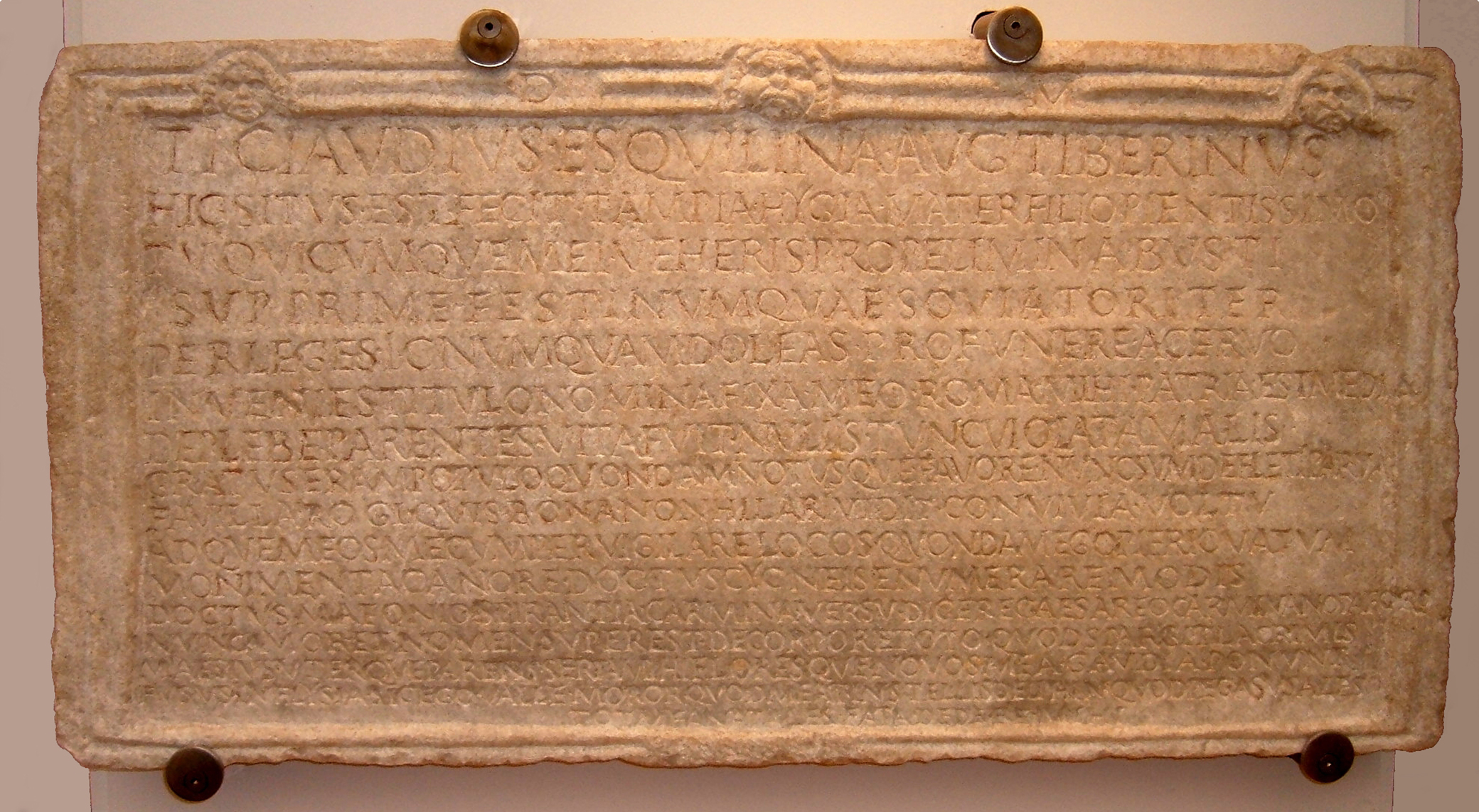

Inscription on the tomb of Tiberius Claudius Tiberinus, Rome. Photograph by Kleuske. Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

He encouraged the talents of his age in every way that he could. He listened courteously and patiently as they read not only poems and histories but also speeches and dialogues. But he was offended when anything was written about him that was not serious and by the most eminent, and he used to warn the praetors not to let his name become degraded in competitions.

Consistently misinterpreted by commentators, the third sentence of this revealing passage from Suetonius offers important evidence about authors and their public in Augustan Rome.

The praetors were in charge of the regular annual ludi, from the Megalenses in April to the Plebeii in November, adding up each year to fifty-six days of “stage games” in the theaters and piazzas of Rome and seventeen days of “circus games” in the Circus Maximus. These were the times when a poet or prose author might hope to bring his work to the Roman people, taking his turn among all the varied types of instruction or amusement that were needed to fill those days from morning till night. But how did he get on the praetor’s program? If he was one of “the most eminent,” he might expect to be invited; failing that, he would have to enter one of those competitions.

We know about them indirectly, from poets who did not compete. Horace was content to perform to the small but distinguished private audience at Maecenas’ house:

These things I play about with aren’t meant to resound in the temple, in a competition with Tarpa as judge, or to come back again and again as theater shows.

As one who listens to noble authors and avenges attacks on them, I don’t see fit to canvass literary constituencies and stages. That’s what causes the trouble. If I say, “I’m ashamed to recite my unworthy writings in crowded theaters and add weight to trifles,” then someone replies: “You’re laughing—you keep your stuff for the ears of Jove.”

Propertius too claimed to write only for private approval:

Once I achieve that, it’s goodbye to the public’s confused talk. I’ll be safe with my mistress as judge.

Clearly it mattered who was doing the judging. A fragment of papyrus preserves part of a line of Cornelius Gallus, “I’m afraid with you as judge, Cato,” evidently addressing the Valerius Cato who was known as “the one selector and maker of poets.” Like Maecius Tarpa, mentioned by Horace, Cato seems to have been a literary arbiter for the praetors, choosing the best for their programs at the games.

There is much that we don’t know, and it is important not to ignore evidence that opens up an unfamiliar perspective. One item that has not received the attention it deserves is the inscription from the tomb of Tiberius Claudius Tiberinus, found in the eighteenth century not far from the Baths of Caracalla.

Tiberinus was an Augustalis, a member of the humble priesthood created by Augustus in 7 bc to look after the new cult of the Lares Augusti (and his own Genius) at the crossroads of each neighborhood in the city. Augustales were usually freedmen, but Tiberinus was freeborn and proud of it, pointedly spelling out in full (it was usually abbreviated) the voting district Esquilina in which he was enrolled. The distinctive forename suggests he was the son of a freedman of a patrician Tiberius Claudius—perhaps Livia’s first husband, or his son who became Tiberius Caesar, or his grandson who became the emperor Claudius.

Tiberinus died in his late twenties, and his mother, who put up the tomb, arranged for him to tell his story with a fine epitaph in elegiac couplets:

You traveler, whoever you are who ride by the threshold of my tomb, please check your hurried journey. Read this through, and so may you never grieve for an untimely death.

You’ll find my name attached to the inscription. Rome is my native city, my parents were true plebeians, my life was then spoiled by no ills. At one time I was well known as a favorite of the people; now I’m just a little ash from a wept-over pyre.

Who didn’t see good parties with a laughing face, and (who didn’t see) that my cheerfulness stayed up late with me? At one time I was skilled in reciting the works of bards with Pierian tunefulness in swan-like measures, skilled in speaking poems that breathed with Homeric verse, poems well known in Caesar’s forum.

Of all my body, which both my parents sadly strew with tears, love and a name are now what’s left. They place garlands and fresh flowers for me to enjoy; that’s how I remain, laid out in the vale of Elysium. My fates gave me as many birthdays as the stars that pass in (the signs of) the Dolphin and winged Pegasus.

Although this professional entertainer was evidently available for private parties too, it must have been the public bookings that made him the people’s favorite. The praetor could not always hire poets to perform in person, and in any case a professional performer might do a better job with the poet’s text.

At this point we should think about the most iconic of all works of Augustan literature. Virgil was hugely popular in his lifetime, and everyone knew that his Aeneid would be a masterpiece. Although he himself was never satisfied with it, after his death Augustus made sure the text was preserved. But how did it reach the audience for which it was written? The answer must be through the work of people like Tiberinus, “skilled in speaking poems that breathed Homeric verse.” And of course the audience loved them for it.

Such works were “well known in Caesar’s forum”—a very puzzling phrase. Was it a true toponym, referring to the Forum Iulium begun by Julius Caesar in 54 bc? Or was it a description, “Caesar’s public space,” referring to the Palatine piazza? Either is possible, but since Tiberinus was an Augustalis, the attested association of the Lares cult with specifically Augustan themes and places may perhaps favor the latter.

We don’t know the date of Tiberinus’ epitaph, but his pride in plebeian birth and free citizen status would fit well with the ethos of Augustus’ time. The authority of the princeps was defined as the protection of the citizen body, using the traditional powers of the tribunes of the plebs. His way of life was deliberately unpretentious, as his biographer Suetonius makes clear:

When he was consul he walked about in public usually on foot, and when he was not consul often in an open litter. At his open audiences he admitted even the common people, accepting the requests of those who approached him with such affability that he jokingly reproved one man for hesitating as he held out his petition to him “like a coin to an elephant.”…

Sometimes he would arrive at dinner parties late and leave early, as his guests would start eating before he took his place and would continue after he had left. He used to serve dinners of three courses, or six at his most generous, without excessive expenditure but with utmost conviviality. For he would encourage the silent or those who talked quietly to share in the general conversation. He would intersperse entertainments and actors or even street players from the Circus, and more frequently storytellers.

“Entertainments” (acroamata) were often poetry readings, and it is easy to imagine performers like Tiberinus giving as much pleasure to the guests in Augustus’ dining room as they did to their fellow citizens in the piazza when the games were on.

“He honored with his attention,” says Suetonius, “every category of those who offered their services in public shows.” A conspicuous example was the star dancer Pylades, famous for his bravura performance in The Madness of Hercules. From Macrobius’ Saturnalia:

In this play he even shot arrows into the public audience, and he drew his bow and shot his arrows when playing the same role by order in Augustus’ dining room. Caesar wasn’t offended that for Pylades he and the Roman people occupied the same position.

Of course he wasn’t: why should he be? He was not an emperor in a palace. He was Caesar, who had freed the republic from the domination of an oligarchy. His house was respectable but not luxurious, appropriate for the first citizen (princeps). Only its forecourt made a big public statement, opening on to the piazza he had created from the confiscated town houses of the oligarchs. In that piazza, we have suggested, the poets who were the glory of his age might read or sing their works to the Roman people.

Excerpted from The House of Augustus: A Historical Detective Story by T.P. Wiseman. Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.