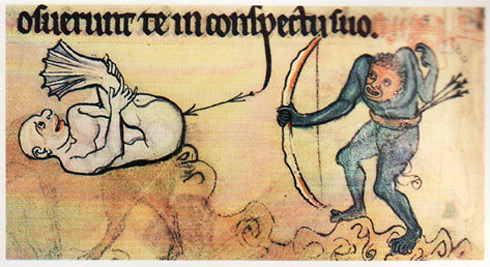

Illustrations from the manuscript Romance of the Rose, by Guillaume de Lorris, c. 1405. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California.

The Means of Communication issue of Lapham’s Quarterly contains a fabulous collection of complains and marginal notes by the monks assigned to copy manuscripts in the era before the printing press. With their bitchy complaints—“I am very cold,” “Oh, my hand”—they insert themselves into the holy texts and often, in the process, disrupt the sanctity of the words they’re supposedly copying: “Now I’ve written the whole thing: for Christ’s sake give me a drink.”

These lovely and lively interjections represent just a small range of expression that one finds throughout medieval manuscripts. And as Michael Camille documents in Images on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art, it is in these marginal comments that we learn as much—if not more—about the medieval world as we do from the texts themselves. Marginalia might include comments like the ones from our miserable monks, but also an entire free-flowing range of artistic flourishes and doodles that make up the edges of medieval manuscripts. “Once the manuscript page becomes a matrix of visual signs and is no longer one of flowing linear speech,” Camille writes, “the stage is set not only for supplementation and annotation but also for disagreement and juxtaposition—what the scholastics called disputatio.”

Marginal illustrations could be profane and bizarre: one manuscript of the romance of Lancelot shows a nun breastfeeding a monkey; another marginal image in the Rutland Psalter features a demon of some sort firing an arrow into the ass of a merman.

Depictions of sexual consort are frequent, among men and women, among various species of animals, and enough other combinations to make even contemporary readers blush. Camille cautions against reading such images as violations of the sacred text; because the medieval world was so rigidly hierarchized and structured, “resisting, ridiculing, overturning and inventing was not only possible, it was limitless.” That these psalters and books of hours often contained sacrilegious sentiments right alongside their holy piety, it seems, was perhaps the point: “We should not see medieval culture exclusively in terms of binary oppositions—sacred/profane, for example, or spiritual/worldly,” Camille explains. “Travesty, profanation, and sacrilege are essential to the continuity of the sacred in society.”

That these books contained such unresolved contradictions in them is what has drawn me to illuminated manuscripts time and time again—though my favorite of these images are those that, like the monks’ marginal complaints, involve the act of writing itself. A 1323 missal illuminated by Petrus de Raimbeaucourt, for example, contains on such picture of a scribe harassed by monkeys: while he tries to copy, they mimic him, drink his ink, and distract him. One moons him, an obscene gesture suggested by a suggestive line break in the Latin above: the word culpa, “sin,” is cut at cul, so that the line reads instead Liber est a cul—“the book is to the ass.”

And then there is the image from a manuscript of The Romance of the Rose, a thirteenth-century epic begun by Guillaume de Lorris and finished by Jean de Meun, in its time as popular and important as The Canterbury Tales and Dante’s Divine Comedy. The Romance of the Rose offers a straight-forward, if increasingly lengthy and digressive, love story—having entered into an allegorical Garden of Love, Amant (the Lover) engages in a series of dialogues on the nature of love and women, before ultimately scaling the castle where his beloved awaits. It is, of course, a narrative by and for the aristocracy: no servants exist in this allegory, nor would anyone but the courtly elite have owned or read such a manuscript.

But while the text itself is focused around this aristocratic world, it was copied and built by tradesmen and the working class, and as Camille suggests, one finds in these marginal notes and images a subtle reflection on the power structure inherent in the medieval manuscript: “The artists who painted these images were sometimes servants in the retinue of the nobility, but even those who were professionals were lower on the social scale than those for whom they worked. Was the servant able to poke fun at his master in the margins in the same way that the Latin fabulist Phaedrus…thought he could?”

Thus the image in a manuscript of The Romance of the Rose held in the Bibliothèque Nationale, illustrated by a husband and wife team, Richart and Jeanne Montbaston, which has become my favorite of all of these strange interjections. In the bottom margin of a single page, the Montbastons’ incorporated a self-portrait of themselves, with Richart copying the letters while Jeanne illustrates. While they may appear initially as nothing more than a visual signature, their presence undermines the entire work of the epic, pointing to a world beyond the allegory of the romance with its gardens of pleasure and castles of jealousy. In a world of women treated variously as deceitful liars or sex objects, Jeanne’s presence as a worker and as an artist in her own right questions much of the assumptions the Romance’s authors make, and in their depiction of themselves in the process of making the very text we are reading, they proclaim the manuscript as manuscript, as a material object—inviting us to consider not just the terms of the allegory, but the literal surface on which it rests, and a reminder of the lowly craftsmen who lie always behind great works of literature and make them possible.