Portrait of a Lady, by Rogier van der Weyden, 1460. National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Collection.

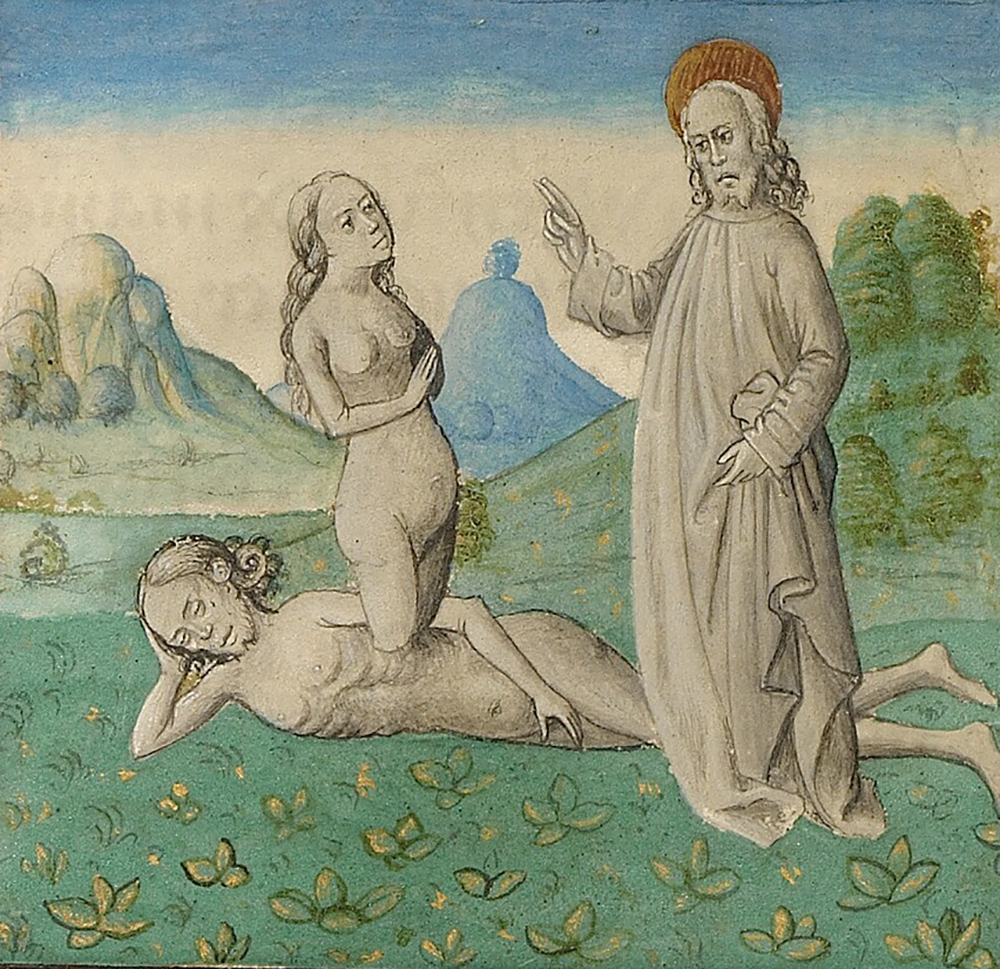

The idealized beauty of medieval literature did not end at the glorification of specific facial features and hair. The male gaze was more than happy to wander down a woman’s body. Not surprisingly, the beauty ideals for the body were as rigid as those for the head. As medieval literary scholar Edmond Faral has pointed out, these descriptions followed a top-down order, almost as though checking features off a list:

The hair

The forehead

The eyebrows and the space between them

The eyes

The cheeks and their color

The nose

The mouth

The teeth

The chin

The throat

The neck and its nape

The shoulders

The arms

The hands

The breasts

The waist

The belly

The legs

The feet

This makes some sense, given that medieval writers loved guidelines, and that this list follows a generalized pattern of recognition of how people look at one another. Notwithstanding those gentlemen who occasionally need to be reminded of where, exactly, a woman’s face is, most people scan other humans starting with the head, given its proximity to their own, and working their way down to the feet, should they be interested enough to learn more.

So we too now find ourselves moving to the body, in the order of the medieval list. We begin with the neck, which is often described in vague terms. Matthew of Vendôme used the whiteness of snow for a neck’s beauty. Geoffrey of Vinsauf used an architectural analogy, seeing the feminine neck as long and white like a column. Most other neck descriptions agree that they be long and white. By the later medieval period, some poets expanded the repertoire of similes to note that a beautiful woman has a neck “like a swan.” Iberian writers, instead, sometimes compared it to that of a heron or even an antelope, but white and long it remained.

We can move quickly past the shoulders, since once again they are almost universally praised for being white and smooth, and move on to arms and hands. Never let it be said that medieval literature offered no diversity in women’s bodies. The French poet Guillaume de Machaut was for “arms long and straight,” but Chaucer interchangeably praised “small,” “slender,” and “plump” arms. Perhaps arms weren’t high on the medieval list of sexy things. What seems to have been most important was that a woman’s arms be white and soft like the rest of her body.

There might have been more room for diversity in arms, because hands and fingers were more often the focus. Hands were uniformly spoken of as white and were often said to be soft and long. The emphasis on whiteness and softness is again a clue about which women might be able to live up to such a literary beauty ideal. Soft white hands were the province of wealthy women who were not planting the fields in all weather, hand-washing clothes and dishes, and wrangling farm animals. Having said that, many writers simply didn’t care enough about hands to dwell on them. Geoffrey of Vinsauf, for example, was happy to rush past them, expressing more interest in how his beauty’s arms flowed into hands with long fingers. Matthew of Vendôme’s Helen of Troy, on the other hand, simply had hands that did “not shake with flabby flesh.” All in all then, hands were meant to be noticed, but provided they were white, soft, and long, there was wiggle room in how one could write about them.

The relatively scant discussion of arms and hands landed medieval writers somewhere that our own society (and certainly the legions of evolutionary psychologists) likes to place emphasis—the breasts. If you as a modern reader are excitedly hoping for tales of heaving bosoms spilling from gowns, I am afraid I have disappointing news for you. Medieval men were uniform in their description of the perfect set of boobs as decidedly small and white. Matthew of Vendôme praised the “dainty” breasts of Helen of Troy, which lay “modest on her chest.” Geoffrey of Vinsauf meanwhile wrote that the ideal beauty’s breasts were like gems and were only a “brief handful.” Machaut, adding more adjectives to the discussion of a young woman’s chest, nonetheless took pains to emphasize that while they were “white, firm, and high-seated / pointed, round,” they were also “small enough,” perhaps indicating that in an ideal world her cups would overflow a bit less.

An interest in small breasts is of note because this ideal too was easier for the wealthy to live up to, as they could opt out of breastfeeding. Most mothers undoubtedly nursed their own children, but wealthy women could employ wet nurses to do so in their stead. Women of the nobility and royalty simply bound their maternal breasts up, to ensure that they shrank back down to a pleasing size, and left it to the lower-class women in their employ to feed any and all screaming mouths. The wet nurse as the preferred method of keeping breasts small is testified to in the Trotula, a twelfth-century medical guidebook, in a segment called “On Conditions of Women,” which devotes an entire section to “Choosing a Wet Nurse.” Funnily, any good wet nurse should have the preferred beauty attributes found among the nobility, “redness mixed with white…who is not blemished, nor who has breasts that are flabby or too large…and who is a little bit fat.” In this way, well-off women had the ability to keep the dainty breasts that were so preferred, while also ensuring the beauty benefits of a good night’s sleep.

While our culture might not share medieval writers’ interest in small breasts, we do have a tendency to feel the way they do about waist size. Medieval people appear to have preferred a smaller one, although they tend not to be lavish in their descriptions. Matthew of Vendôme assured his readers that Helen of Troy’s “sides were narrow at her waist.” Later, Machaut’s gave beauty this rundown: “in proportion…amply fleshed, long, straight, pleasing, resilient, agreeable, and svelte.”

If the desire for women to be both “amply fleshed” and “svelte” seems like a contradiction, it is resolved as the theoretical eyes of the writer and reader scan downward. From the waist they light on, per Matthew, “the luscious little belly.” Modern readers might think that this is a reference to a flat belly to match the small waist. Instead, Matthew and his cohort were speaking of their delight in a pot belly, which “rises” outward, hearkening back to Machaut’s reference to his beauty being “amply fleshed.” Elsewhere the same preference for a belly is referred to as a softness or a swelling. When poets made no specific reference to bellies, they often expounded on the long torsos of the beauties that inhabited their minds. One way or another, medieval writers were emphatic that they in no way favored women skipping lunch.

Once again, an interest in protruding and enlarged bellies was indicative of a preference for the looks of the rich. Most women, as peasants, were involved in doing manual labor and breastfeeding their own kids. As such, they had ample opportunity to burn off any calories that they ingested. A refined life at court, or indeed in a merchant’s household, was much more sedentary. Women certainly worked in those contexts, but that work had much more to do with diplomacy or keeping accounts or indeed sewing, which could all be accomplished comfortably with their feet up. Moreover, rich women were more likely to have the sort of food on the table that helps cultivate a belly. Sweets, white bread, and fatty meats were much easier to come by with money. All in all, then, wealthy women had a head start in the belly stakes.

As writers moved on to the legs, they tended to treat them in two separate parts. They almost universally agreed that a leg should sport a “fleshy,” “well shaped” thigh. Interestingly, at times this preference comes across as an oblique hint at genitalia. Matthew, for example, referenced the “sweet home of Venus…made hid” by the “festive adjoining areas,” which is to say the thighs. This description wouldn’t be misplaced in any modern bodice-ripper and serves as a reminder that while in theory such descriptions of beauty resemble an academic exercise, they still carry a sexual charge. Then as now, when writers explained beauty, they meant for their audiences to believe their descriptions and to acknowledge their expertise with such charms. Geoffrey seems to have seen the inflamed passions of his audiences coming and instead pointedly declined to describe the thighs, or what was between them, because “say[ing] nothing of the parts below…more aptly speaks the language of the heart.” Both authors absolutely knew that the images they conjured were sexy. The only difference was that Matthew wanted to connect that to a specificity, whereas Geoffrey left his audience to fill in the blanks, even if he risked opening himself to criticisms about a lack of firsthand knowledge on the subject.

Legs were a less sexy endeavor. Authors uniformly praised their length, their fullness, and sometimes their straightness as well. Geoffrey’s coyness fell away when he asserted the fine length of his beauty’s shins. Machaut felt a need to mention the legs as a body part separate from the thighs, but he happily called them “well shaped” and let his audience do the rest of the heavy lifting.

After the titillation that the thighs provided, the feet were anticlimactic, as authors systemically, to a man, dutifully described the ideal—small—foot. Some called it dainty or praised long, straight toes. However, just when you might conclude that descriptions of feet lack the giggling poetic excitement of thighs and legs, Machaut swoops in to call out “the feet, arched, plump, and well formed, cunningly shod with exquisite shoes,” of his ideal beauty, spending more time there than on the thighs, legs, and hips combined.

While the ideal medieval woman had a certain set of characteristics that we can even arrange on a checklist, one final factor was occasionally voiced as well: age. We certainly identify age as a generalized “young,” but for medieval people, years on the planet didn’t serve to convey the meaning that they were attempting to indicate. Men who were engaged in conjuring the ideal beauty into existence thought a woman, in order to be truly beautiful, had to be not just young but also sexually inexperienced. In other words, she had to be that medieval construction: a maiden.

In the medieval period, the term maiden referred generally to the stage of life that loosely maps to our own concept of the “teenager.” Maidens, much like teenagers, were no longer children but had not yet attained full adulthood. Maidenhood, like the teen years, was a transitory stage. But the term also implied a sexual maturity that had not yet been acted on and as a result was a “perfect” sort of femininity.

This state of “perfection” was in turn linked to a totally different way of considering aging in humans. Contrary to some of our more persistent myths about the medieval period, “maidens” were quite young not because of a short medieval life expectancy. Medieval people lived about the same life span as we do now, provided that they managed to survive infancy and (in the case of women) childbirth. The idea that the “average medieval person lived until thirty-two” is a misreading of what average means. About 50 percent of medieval people died as infants, an incredibly sad statistic that remained largely true until the development of vaccines and modern medical interventions. So if half of the population died before the age of one year, then in order to get an average life span in the thirties, the other half of the population had to live into their seventies (if you remember your basic math). And this was indeed the case! As a result of a fairly long life, the majority of people married in their twenties, much as they do now. So it would be incorrect to refer to an eight-year-old as a maiden, as she was still simply a girl. A maiden was young and a virgin, but she was also, in theory, of marriageable age.

Maidens were beautiful, kind, calm, chaste, pure, delicate, modest, and humble. Also, and very crucially, they were sexy, but they weren’t sexual. This is remarkable, because it’s difficult to conceive of a form of young womanhood that clashes so wholly with our concept of teenage women. Moreover, it perfectly encapsulates how (like the studious inventory of beautiful women) the very concept of maidenhood was invented purely in the heads of men. Maidens were everything that a woman could be without all of the inconvenience of being an actual person with needs, opinions, and complaints.

This concept was not simply a conviction in the minds of lascivious men writing impossible women into existence. Rather, it was fostered from the revered minds of philosophers. Maidenhood was considered to be the “perfect age” for women because they were not only mentally developed and feminine but also, crucially, like men in terms of humoral composition. All children were thought to be hotter and dryer than their older iterations. Advancing age, and death itself, were both associated with wetness. As a result, girls were more masculine than older women because they had not yet become cold and wet. This hot and dry characteristic helped girls burn off their superfluous humors with ease. The sign that they were becoming cold and wet was menarche, when the hot and dry character wore off and the body had to expel excess blood instead of burning it off. Maidens were then perfect, because they were women enough to be distinguishable from men but not so cold and wet that they became deathly.

While it is easy to focus on the ideal, maidens lived with the weight of all these expectations on their shoulders. Not only were they expected to exemplify all of the best and most positive things about women, but a timer was ticking. The moment that they lived up to the promise of their maidenhood and became wives and mothers, or even worse sexual but unmarried, they would lose the status that made them desirable in the first place. Even if a woman navigated this particular tightrope by cleaving to her virginity, there was no hope for her. The march of time would see to it that coldness and wetness, the essence of her femininity, crept in, sweeping her toward decrepitude and eventually death. Still, eschatologically speaking, any virtuous woman would be rewarded at the Apocalypse by a return to her ideal stage and could then look forward forever to being surrounded by perfect men who appeared to be in their thirties.

Excerpted from The Once and Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society. Copyright © 2023 by Eleanor Janega. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.