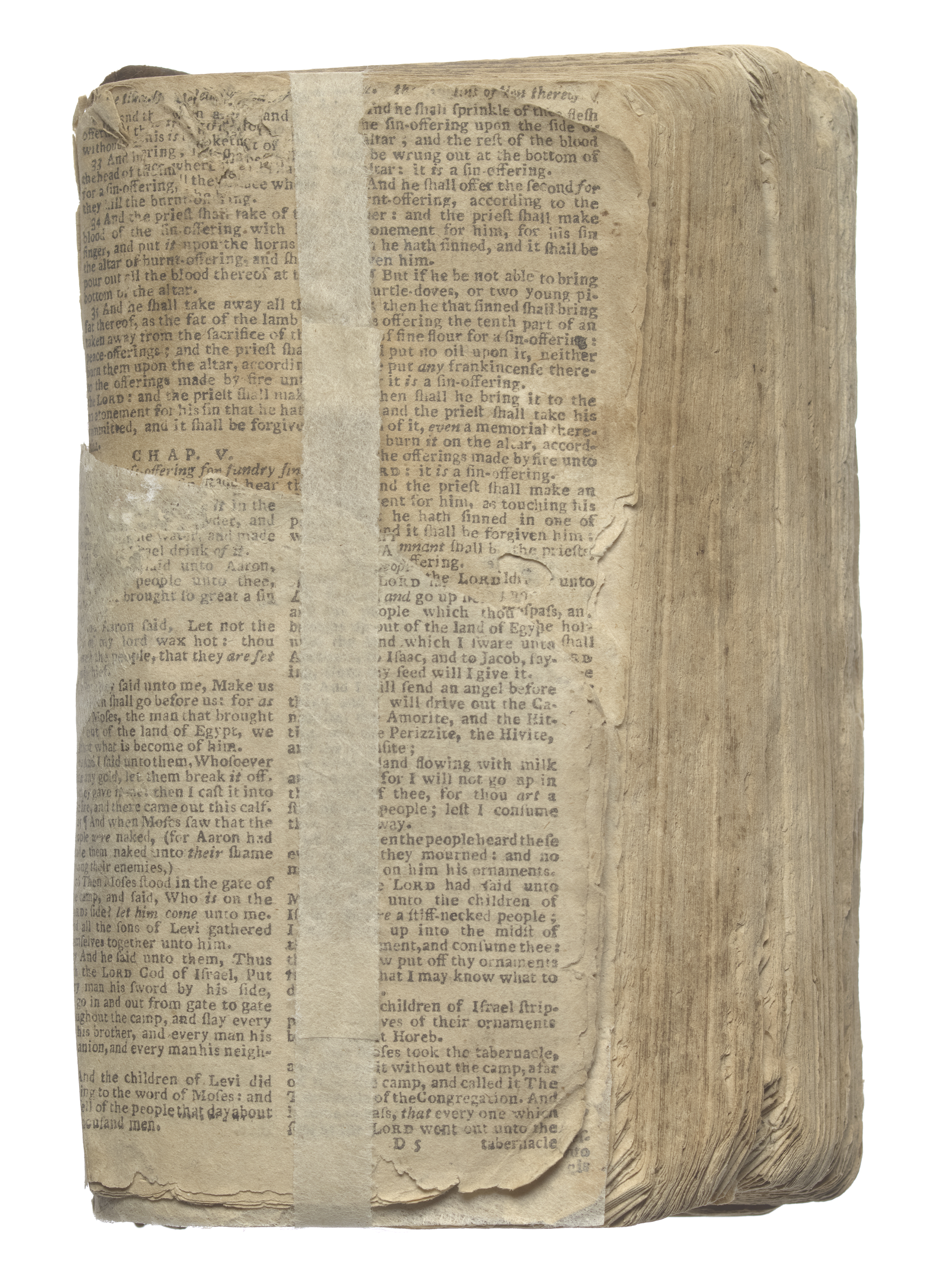

Bible belonging to Nat Turner. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Maurice A. Person and Noah and Brooke Porter.

In 1967 the American novelist William Styron published his third major work of fiction, a book entitled The Confessions of Nat Turner. Styron’s Confessions represented itself as the autobiographical narrative of an African American slave, known as Nat Turner, who in August 1831 had led a slave revolt in Southampton County, Virginia, not far from Virginia’s southeastern tidewater region where Styron himself had grown up. Both Turner and the event that bore his name were real enough—Styron took his title from a pamphlet account of Turner and of his rebellion that had been published in November 1831, a few days after Turner’s capture and execution; his book’s point of departure was the series of conversations between Turner and the pamphlet’s publisher, a Southampton County lawyer named Thomas Ruffin Gray, that had occurred while Turner was in jail awaiting trial and on which Gray drew heavily in constructing his pamphlet. But for Styron the man revealed in those conversations was a person with whom he wished to have nothing to do, “a person of conspicuous ghastliness,” utterly beyond moral reclamation. The Turner of record, Styron emphasized—confidently, consistently, repeatedly—was “a ruthless and perhaps psychotic fanatic, a religious fanatic,” a “madman,” a “dangerous religious lunatic,” a “religious maniac, a psychopath of almost fearful dimensions,” a “demented ogre beset by bloody visions,” who had led “a drunken band of followers on a massacre of unarmed farm folk.”

And so, claiming “a writer’s prerogative to transform Nat Turner into any kind of creature I wanted to transform him into,” Styron invented his own Nat, a sexually inhibited, homoeroticized celibate, whose actions were driven not by eschatological fervor but by an “exquisitely sharpened hatred for the white man” learned over many years from the quotidian mortifications of his dehumanizing and emasculating condition of enslavement.

His violent rebellion is not mindless slaughter but a rational, though tragically misguided, response to the behavioral degradations, disappointments, and humiliations of his enslavement. The agent of Turner’s redemption is the young and virginal Margaret Whitehead, the one person the historical Nat Turner is recorded as killing during the rebellion that bears his name, who becomes in Styron’s hands both object of Turner’s sexual desire and his sacrificial savior, through whom (in a masturbatory fantasy minutes before his execution) Turner recovers his unity with the God he believes has abandoned him because of his bloody rampage. “Perhaps,” wrote Styron, “she had tempted him sexually, goaded him in some unknown way, and out of this situation had flowed his rage…It was my task—and my right—to allow my imagination to range over these questions and determine the nature of the mysterious bond between the black man and the young white woman,” for in their bond (and their mutually determined fate) lay the symbol he sought, the “dramatic image for slavery’s annihilating power, which crushed black and white alike.”

Why, one might wonder, did the William Styron who had been obsessed by the story of Nat Turner since he was a boy, and who had felt an urge to explain him to modern America ever since he became a writer, nevertheless make no attempt to comprehend the Turner whom he actually encountered in the sources he consulted (“I didn’t want to write about a psychopathic monster”)? Why “re-create” Turner in a persona that might be “better understood”? The answer lies in what Styron represented as an act of self-expiation that was also and simultaneously an act of regional and even national expiation, an act that led him to claim that his Confessions was not a “‘historical novel’ ” but a “meditation on history.”

By re-creating Nat Turner and his motives, Styron sought respite from American history’s violent racial storm in cathartic reconciliation with (through knowledge of) “the Negro”:

No wonder the white man so often grows cranky, fanciful, freakish, loony, violent: how else respond to a paradox which requires, with the full majesty of law behind it, that he deny the very reality of a people whose multitude approaches and often exceeds his own; that he disclaim the existence of those whose human presence has marked every acre of the land, every hamlet and crossroad and city and town, and whose humanity, however inflexibly denied, is daily evidenced to him like a heartbeat in loyalty and wickedness, madness and hilarity and mayhem and pride and love? The Negro may feel it is too late to be known, and that the desire to know him reeks of outrageous condescension. But to break down the old law, to come to know the Negro, has become the moral imperative of every white Southerner.

Styron’s “social and behavioral” explanation pulls Turner into Styron’s present in order to capture and complete him. By explaining this particular Negro, Styron will come at last to know and to explain the Negro. He will fulfill the felt moral imperative; overcome the old law of suppression, suspicion, and separation; lay the ghost; and earn redemption for himself, every other white Southerner, and arguably the nation as well. Completion of the past relieves and completes the present.

The attempt was, of course, hopeless. The Negro was a wholly white ideological-cultural construct (albeit one with a very long history), nonexistent as such, hence unknowable in any form that could satisfy Styron’s desire “to know the Negro.” Styron’s Nat was the figment of a white authorial imagination that, notwithstanding Styron’s insistence that he had respected “the known facts,” sedulously refused to listen to any of Turner’s own explanations of himself. Yet this fatally flawed exercise was neither uninfluential nor unimportant. As a published book Styron’s Confessions was a major commercial success. Book club and paperback rights had been sold long in advance, bringing $250,000. Movie rights went for $800,000. The next few years saw multiple foreign editions and a Pulitzer Prize (1968). It became one of the principal channels through which white America, in the midst of its confrontation with civil rights agitators, Black Power, and the urban riots of 1967 and 1968, renewed its acquaintance with slavery and slave rebellion.

It generated intense controversy within late 1960s academic and “public intellectual” circles, largely in the form of a series of confrontations between African American intellectuals who attacked Styron’s depiction of Turner and of slavery and Styron’s self-appointed defenders, notably the bumptious polemicist of American slavery and defender of the American South Eugene Genovese. And it stimulated critical assessment of the novel’s fictive realities and their relationship to the representation of historical events. In all these respects, Styron’s claim that his work was no “historical novel” but a “meditation on history” was, perhaps intentionally, deeply provocative, for it ensured that his fictive depiction of reality would continuously challenge, rather than simply be haunted by, the shadowy presence of that with which the depiction did not accord.

In a New Republic review C. Vann Woodward, the doyen of white Southern historians, awarded Styron the mantle of complete and utter scholarly respectability. “The picture of Nat’s life and motivation the novelist constructs is, but for a few scraps of evidence, without historical underpinnings, but most historians would agree, I think, not inconsistent with anything historians know. It is informed by a respect for history, a sure feeling for the period, and a deep and precise sense of place and time.” A man one might consider Woodward’s African American counterpart, John Henrik Clarke, did not agree. “No event in recent years has touched and stirred the black intellectual community more than this book. They are of the opinion, with a few notable exceptions, that the Nat Turner created by William Styron has little resemblance to the Virginia slave insurrectionist who is a hero to his people.”

Nine other black intellectuals joined Clarke in publishing a book of essays claiming the existence of a potent African American history (and lore) of Nat Turner ignored by Styron and attempting to reclaim the historical figure of Turner from him. With perhaps two exceptions, their rebuttal—William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond—though heated, was not unduly rancorous. Nonetheless they were speedily condemned by Styron’s defenders, notably Eugene Genovese, for a collective exhibition of “ferocity and hysteria” that revealed the black intelligentsia was on course for a “moral, political, and intellectual debacle.” Nothing had ever prevented “black intellectuals, who claim to have the living traditions of black America at their disposal, from creating their own version” of Turner, Genovese wrote, even as he busily set about denying that black America’s living traditions actually contained any memory of Turner, and excoriated the ten’s attempts to defend an African American “version” as mere pandering to the Black Power movement. “If white historians—for whatever reasons—have been blind to whole areas of black sensibility, culture, and tradition, then show us. We can learn much from your work but nothing from your fury.” Subsequently, Styron himself would claim the ten black writers were no more than a front for the U.S. Communist Party and its apparatchik theoretician Herbert Aptheker, the white historian of slavery whose work Styron—like Genovese—publicly derided.

No one was more admiring than the literary critic Philip Rahv in The New York Review of Books. Styron had successfully matched his subject—chattel slavery and its consequences—to the moment, “the political and intellectual climate of the Sixties.” The novel’s historicity did not exclude, but rather invited, contemporaneity in a way that “only a white Southern writer” could have managed. A Northern writer would have been too much of an outsider, Rahv argued, “and a Negro writer, because of a very complex anxiety not only personal but social and political, would have probably stacked the cards, producing in a mood of unnerving rage and indignation, a melodrama of saints and sinners.” Styron had surpassed Faulkner in his “ability to empathize with his Negro figures.” His book was “a radical departure from past writing about Negroes”; it fulfilled its author’s desire “to know the Negro.”

The helpless, hapless, condescension of reviewers like Rahv helps explain the appalled reaction of John Henrik Clarke and his compatriots, whose essential complaint was pithily summarized in historian Vincent Harding’s essay title, “You’ve Taken My Nat and Gone.”

Excerpted from In the Matter of Nat Turner: A Speculative History by Christopher Tomlins. Copyright © 2020 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.